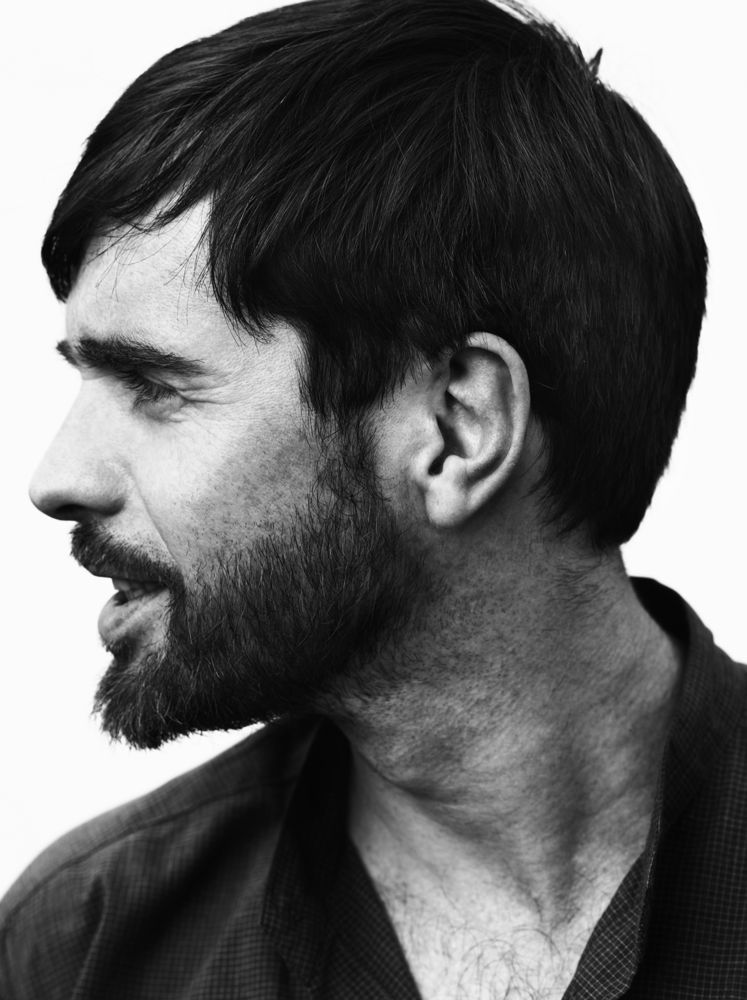

Christophe Lemaire

I think the epitome of elegance is when you see a man or a woman on a street corner, on the bus, or on vacation, and you ask yourself, ‘Who is that?’ Christophe Lemaire

Just before the grand depart, France’s month-long August summer break, Christophe Lemaire, the designer of Hermès womenswear, is on the rooftop of a multilevel garage in Paris. This one provides a rare 360-degree view of the city’s many slate-gray rooftops. It’s an appropriately high-altitude place to photograph his Hermès woman, whose position in matters of style appears blissfully above the fray. It has been a jam-packed year for Lemaire, who designs his own eponymous lines for men and women in addition to his collections for Hermès, where in his fifth season for the house, he has achieved a kind of breakthrough, a wardrobe of clothes that blends its rich heritage with an understated, uniquely Gallic mode of chic. This restrained quality is, in fact, his signature, a wearable simplicity that transcends trend, a kind of fashion that pulls from everyday style, reinventing the classics.

The nephew of Robert Caillé (who published French Vogue in its Francine Crescent days), the French-born Lemaire, now 48, spent his childhood surrounded by elegant women. Prior to joining Hermès, he already had a well-established reputation as a designer in fashion circles, albeit one removed from the glamorous social swirl inhabited by some of his contemporaries. A two-time winner of France’s ANDAM prize, he interned at Yves Saint Laurent and Thierry Mugler in the early ’80s before assisting Christian Lacroix. In 1991, at the age of 25, he launched his namesake line, and in 2000, he was brought on by Lacoste to reinvigorate the sportswear brand. Lemaire’s coronation as the new design head of Hermès in 2010 was regarded as a bit of a surprise within the industry—especially given the insouciant glitz of his predecessor, Jean Paul Gaultier. But handpicked by Hermès artistic director Pierre-Alexis Dumas—a descendant of Hermès founder Thierry Hermès—the subdued Lemaire has seemed more than in his element.

Hermès has always been more about clothes that people can live in than fashion fantasy, as evidenced by its beginnings in 1837 as a purveyor of equestrian wares. Lemaire elegantly tapped into this more functional element of the brand’s history for his fall 2013 show, staged in the upstairs library of one of Paris’s most elite schools, the Lycée Henri IV, where the bookish surroundings were an apt setting for his crisp button-ups, leather separates, and menswear-influenced outerwear. I spoke with him in Paris.

REBECCA VOIGHT: You’ve been all over the place, from your first internship at Thierry Mugler to Yves Saint Laurent, to the launch of your own brand, to a stint in Japan, to Lacoste, and now Hermès. What’s the common denominator?

CHRISTOPHE LEMAIRE: It’s the idea of making daily life more beautiful and finding poetry in reality. As a child, I developed this fascination for everything that touches decoration, environment, quality of life, and clothing. Little by little, I began to make my mark. I can be quick in daily life, but deep down it has taken me a long time to mature, define my vision, and acquire the self-confidence to express it. I had a kind of imposter complex when I was younger. I didn’t feel comfortable with how the fashion system works. I wasn’t at ease with the nonstop spectacle of it. I’ve always loved designing clothes and had a passionate interest in style, but in a more intimate, not so superficial way.

VOIGHT: You interned at Yves Saint Laurent. What led you there?

LEMAIRE: I arrived at the end of Saint Laurent’s more experimental period, but I was already completely immersed in his style because my mother and grandmother wore Saint Laurent. My grandmother was such an elegant woman. When I was growing up, I spent all of my vacations with her in the south of France, and it was funny because at the end of her life, she began to wear Alaïa. My uncle [Robert Caillé] was the publisher of French Vogue in the 1970s, when the magazine was full of Guy Bourdin’s photos. My uncle was very social, and Helmut Newton wrote about him in his biography. But I wasn’t obsessed about becoming a fashion designer back then. Looking back, I can see that I was just very precise about the kinds of clothes I wanted to wear.

VOIGHT: What were you wearing at the time?

LEMAIRE: Fashion and music were very close in ’79. I was listening to the Specials and was into the 2-Tone movement. I’d go to Marché aux Puces St-Ouen de Clignancourt [Paris flea market], where there was just one stand that sold old Levi’s Sta-Prest pants. I wore Catalina blousons and creepers. As a teenager, I was into new wave and ska, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and Joy Division. Then Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto arrived to show in Paris, and I was completely into that, so I got into fashion.

VOIGHT: After working at Saint Laurent, you landed as an assistant for Christian Lacroix.

LEMAIRE: It all happened so quickly. I started working for Christian in ’86, when he was designing for Jean Patou. I arrived just before he launched his couture house with Bernard Arnault. One morning, I was at rue Saint-Florentin chez Patou, and Christian and Jean-Jacques Picart weren’t there, but they called to say they were launching the house. There was a lot of buzz. The next thing I knew, I was on my way to New York to do a show and then on to Los Angeles. I remember accompanying the clothes and dealing with customs at JFK. I was 21 and in charge of a team of American dressers backstage for the New York show. There was something insouciant and easy-going about fashion in the late 1980s, before the pressure of big business and media took hold.

We’re living in an image-oriented pop culture, but I’ve never been very at ease with that. Christophe Lemaire

VOIGHT: Then you launched your own eponymous line when you were in your mid-20s. What convinced you to do that?

LEMAIRE: I was very impatient. I jumped into the water before I knew how to swim. It was an independent brand, so I had a business with a team of 15 people to manage, but I was also the designer. I wasn’t prepared and so I stopped in 2000, took a break, and relaunched in 2006.

VOIGHT: There was a point in your career when you seemed to have disappeared to Japan. You were doing a lot of DJ’ing and then you were gone. What did you find there?

LEMAIRE: I had a love affair with Japan. I still have it. Japan was a cultural shock for me when I visited for the first time, in ’95. I was invited by my distributor. My collection was successful right away there—unlike in France, where I was not considered conceptual enough at the time. But I had a French side that caught on right away in Japan. I remember we did a show in one of those hyperchic, ’60s Blow-Up-style striptease clubs that you can only find in Tokyo. The girls were topless, but they were all very beautiful and it was not vulgar. I remember asking myself, “What is going on in this country?” It felt like being in London in ’67, only it was Japan. There was something about Japanese culture that got me right away—the sensitivity, subtlety, refinement, sophistication, attention to detail, and the attention they devote to being in the moment.

VOIGHT: Lacoste was one of the first French sportswear brands to get an haute fashion makeover, and they picked you to do it. Taking on the polo shirt must have come as quite a change for a designer who cut his style teeth at Yves Saint Laurent and Lacroix.

LEMAIRE: Yeah, and that’s what I liked about it. I love the Lacoste story, the brand’s values, the elegant sport style, the democratic side. Perhaps it was a bit naive to think I could just walk in and bring style and quality to a brand that’s so accessible.

VOIGHT: After that, Lacoste suddenly looked more chic than mass.

LEMAIRE: Yes. I was inspired by Suzanne Lenglen and the court photos by Jacques-Henri Lartigue. We did some great shows, and it was an exciting change to have girls smiling and looking healthy on the runway. We took this very French idea of chic sport to New York. And strangely enough, I have found the same spirit at Hermès.

VOIGHT: So in 2010, after a decade, you left Lacoste in a very good position, and Hermès came knocking at your door. Were you surprised?

LEMAIRE: I had old memories about Hermès from my childhood. When I worked for Patou, I would pass by the Hermès windows all the time. They were elegant and rich, and that was the first thing that made me think it was a marvelous brand

VOIGHT: Hermès didn’t need a remake, though. It seems like it was more about fusing your style to the brand. What was it like at the start?

LEMAIRE: The first feeling I had when Pierre-Alexis [Dumas] contacted me was a sense of inevitability, but I was also a bit surprised that he thought of me. It seemed quite smart of them to have identified me. But there were a lot of sleepless nights. I didn’t feel like becoming part of another system, but we had the same values and understood each other, so right from the start there was a lot of enthusiasm and confidence. It felt like joining a family, and that’s quite seductive.

VOIGHT: It took you a while to find your groove.

LEMAIRE: There’s nothing worse for a designer than feeling skepticism, incomprehension, or a sense of wait and see, but at Hermès there’s a great sense of dialogue and details. They have a way of putting you at ease. You get the impression that everyone is working in the same direction to do things right, but there’s also a sense of freedom and fantasy that goes back to Jean-Louis Dumas [Pierre-Alexis’s father] and before that. You can see it in the archives, there’s an elegance and lightness.

VOIGHT: The fall 2013/14 collection you presented last March felt like a breakthrough. What clicked for you this time?

LEMAIRE: More than just a fashion show, we wanted it to be a Hermès moment. Hermès isn’t about fantasy, but at the same time, it’s about an idealized femininity. I think the epitome of elegance is when you see a man or a woman on a street corner, on the bus, or on vacation, and you ask yourself, “Who is that?” We wanted something classic, timeless, and chic, but also erotic and strange.

VOIGHT: Did you feel like you achieved that?

LEMAIRE: We worked on details. Sometimes the only accessory would be a ring, like it was the girl’s own. And we perfumed the girls with Hermès’s Poivre Samarcande. I’m not sure the audience noticed that because it was subtle, but the girls knew it, and that made the difference. The styling itself was pretty straightforward, but we spent a lot of time on the casting and the fittings to find the right outfit for the right girl. Then we said to them, “Don’t be a model tonight, be a woman. You’re just passing through this beautiful place and you’re going to meet your lover.”

VOIGHT: So Hermès doesn’t have to shout?

LEMAIRE: It’s about being useful, practical, and of the highest quality more than making a big visual statement. We’re living in an image-oriented pop culture, but I’ve never been very at ease with that.

VOIGHT: At this point in your career, do you still feel like the preparation for each season is a challenge?

LEMAIRE: Yes, but it’s good and I’m not thinking too much about it. There’s no time. For example, today was the first day I had to spend a few hours at the Musée d’Orsay. I spent an entire hour in the Odilon Redon room. He’s one of my favorite artists. He once said something like, “You can’t explain what you do because you don’t know yourself.” There’s a layer of references that has built up over the years and now it’s almost instinctive. It’s a kind of mysterious breeding ground, and I like it like that way.

REBECCA VOIGHT IS A WRITER WHO LIVES AND WORKS IN PARIS.