Meet Tommy Pico, the Native American, Beyonce-loving poet

PHOTOGRAPHY BY NIQUI CARTER

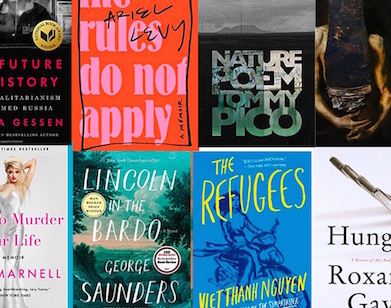

Tommy Pico’s poetry will have you nodding along at the questionable “onslaught of James Franco” or the perils of OKCupid in one breath, and confronting the trauma of genocide the next. To date, he’s the author of three book-length poems. IRL [2016] is a rumination on what it means to be queer, Native American and obsessed with “boys, burgers, booze.” Nature Poem [2017] turns colonial “noble savage” stereotypes on their head. Now comes Junk, a break up poem exploring personal and cultural loss, Janet Jackson, and nacho cheese, which is set for release this May.

Pico originally left the Viejas Indian reservation of the Kumeeyay Nation to study pre-med at Sarah Lawrence, hoping to return to the reservation to address some of the health problems he grew up surrounded by. Instead, he spent his twenties pioneering the artist collective Birdsong, making zines, publishing his poetry on Tumblr, and honing his performance skills through “exposure therapy.”

On the eve of his 30th birthday, Beyoncé’s visual album dropped, and Pico began to consider his short poems as the beginnings of an epic work. After publishing IRL, Pico co-founded Food 4 Thot, a podcast that’s part trash talk, part literary criticism, and wrote his first screenplay.

We caught up with Pico to discuss how he helps make young, Native American, queer people feel seen through his work. A few days later, Pico was awarded a $50,000 Whiting Award, a prestigious literary prize with an alumnus that includes David Foster Wallace, Jeffrey Eugenides and Lydia Davis.

TARA KENNY: You’ve been seriously busy lately, traveling around the country reading and teaching at colleges. How’s that been?

TOMMY PICO: I’m only in any given place for 24 hours. I’m with people all the time, but I’ve only known any of them for 20 minutes. It’s an amazing and weird life, but also so lonely. I’m absolutely not complaining—this is the life of my wildest dreams—but I kind of wish that when I’m in my hotel room in a bath robe having a glass of vinho verde that I have someone to do that with. It makes dating utterly impossible!

KENNY: So this life has come out of you having published three book-length poems in a very short period of time; IRL in 2016, Nature Poem in 2017, and Junk is coming out this May. What’s the relationship between the books?

PICO: I’m actually working on the fourth book now, and when I finish, that will make it four books in four years. Each of my books came out of a line in the previous book. So in IRL there’s a line that’s like, “I hate nature bc every poem is like poplars and bunch grasses and peonies and shit.” That idea became Nature Poem. In the second book there’s a passage that’s like, “I used to read a lot of perfect poems, now I read a lot of Garbage by A.R. Ammons.” I wrote Junk in response to Garbage, which is an epic work of poetry. And then in Junk there’s a passage where I talk about actually trying to find nourishment from food and social interactions, and that’s become my next book, Food.

I’ve been writing forever, but I didn’t actually start writing book-length poems until 2014, after Beyoncé’s visual album came out and I was like, “I’m home!” I didn’t see it as a collection of songs like normal albums, but as a deeply epic body of work. I see Beyoncé as a pop artist who is now making epic work, which is really exciting to me.

KENNY: Did that album influence you to write IRL?

PICO: Well, it came out at the right time for me! Her album dropped at midnight on my 30th birthday, and it felt like a gift. I remember poring over it and understanding how the videos and songs were connected as an album-length work. I was doing short poems, and a lot of the criticism I was getting was that my work ended too quickly.

KENNY: You wrote a screenplay commissioned by Cinereach last year. Are you interested in crossing over to that world?

PICO: Absolutely! I would actually like to make money from writing, and a best seller poetry book is never going to sell as much as Fire and Fury, you know? What a lot of poets do is work our side hustles to make sure we can write our books. I want my side hustle to be writing instead of like, managing a realty management company. I hate writing—it’s hard work and I don’t like it—but it’s the work that I resent the least. When I’m doing other kinds of work I’m like, why aren’t I writing?

The experience of writing the screenplay was very interesting. I had to learn how to make a new medium my own and bend it back towards my voice, rather than change myself into a whole new writer to fit a genre. In doing that, I realized my capability to do that with everything. When you learn the formula, a screenplay stops being an obscure, magical thing.

KENNY: But surely creating believable characters isn’t a formula?

PICO: Yeah, that was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. In poems you can have characters and narrative and dialogue, but you don’t need any of those things. In a screenplay you need them, and you also have to understand conflict as the bare minimum for an attractive piece of cinema. The studio kept telling me to “increase dramatic tension.” I had to give my characters secrets, and have them not want the best for each other. It put me in a weird place. I was constantly thinking about what I would do in a given situation if I were the worst person ever. I’m not someone who just generates creativity and writes stories about spies in Russia! I hone in on real situations writ large, which left me kind of depressed towards the end of the summer and into the fall.

KENNY: Many of those everyday situations you hone in on are uncomfortable race-related interactions. Some guy at karaoke yell-asking you what your nationality is, or a kid calling you a “good Indian” for picking up a piece of rubbish. It kind of reminded me of the TV show Atlanta, in that a white audience, or in this case non-Native American, may cringe at some level of self-recognition. Are you trying to evoke that discomfort?

PICO: When I was writing the book I didn’t feel like I was capitulating to a white audience or having them in my consciousness. But to be able to write from that perspective took a lot of work. In order to get to the point where I was able to center my writing in my own perspective, I had to really understand that centering someone else was just putting off having to engage with myself. I had to really commit myself to being completely alone. It was about understanding that my process and voice is valid, and that I deserve to take up space.

When you get into creative mediums and the gatekeepers are people who don’t look like you, and who might not be your sexuality or gender, they’re still the ones you have to pay fealty to. You have to appease them in order for your writing to be “good.” If David Lehman of The Best American Poetry—this white dude—thinks the poem I wrote is good, it’s good. When the white perspective is seen as the universal perspective, it can be very demoralizing.

KENNY: Do you see sharing a Native American perspective as a way of giving something to your community? I ask this because I know you once did pre-med in the hope of addressing some of the health issues on your reservation, and you’ve talked about wanting to start a mentoring program for young Native American artists. Or do you reject the notion that you represent anyone other than yourself?

PICO: When I was writing the books, I didn’t think that anyone but me was ever going to like them. I wasn’t writing in a reparative way for Native American communities. It was purely selfish. I was just making these comparisons, making these jokes, but then also talking about genocide. LOL, let’s just put that all together! Then I started going to colleges and I was interacting with younger American Indian artists, writers, structural engineers, or whatever, and they’d be holding my book and telling me how much it meant to them. I didn’t understand that people were going to come up to me and tell me that they felt so seen because I was writing about Native issues but also about being queer.

Whenever someone comes up to me at a reading and tells me that I say, “This is as much yours as it is mine. I can’t claim indigeneity or queerness as my ‘thing.’ It’s something that I share with people, which means the book is also something that I share with people.”

KENNY: Has your awareness of your audience changed as it’s grown?

PICO: It’s a constant exercise in forgetting and denial, I would say. One of the great things that’s happened is that now I have resources to commit to more ambitious work. The fourth book, Food, is about me creating a new food ritual and vocabulary, after my access to indigenous ways of cooking and gathering food were destroyed in my grandmother’s generation. A lot of it goes down in people’s kitchens, and now I have some money so I can go visit people in Chicago or San Francisco, or wherever.

I’m trying to appreciate the resources and access without thinking that now I have to make something really good, or something that’s even more representative of indigenous people. I have to make it as low stakes as possible.

KENNY: Totally. So I know you came up as a poet on Tumblr, and making zines in the punk scene in California. How does that fit with the New York and wider literary community?

PICO: When I first moved to Brooklyn at 22 I was trying to find a poetry or arts scene to be a part of and I couldn’t find one, so I just started my own. It was a collective of poets, writers, artists and musicians called Birdsong Collective. I would make 100 zines, leave them out on the streets of Brooklyn, and we’d have a release party every other month. Similarly to the way I spoke about writing from my perspective, this was community building from our perspective. It was an active decision not to assimilate into any other group.

I had to create my own publishing opportunity because no one was publishing me. I needed more stage time and frankly no one was asking me to read back then, so I had to create my own stage. Over the five years that I made the zine and heralded the collective, I got a lot better at writing and performing. It was exposure therapy; I made myself do it all the time.

KENNY: Well, anyone who’s listened to Food 4 Thot or heard you read will know you are an amazing performer. In the podcast you’ve talked about growing up listening to your father (who was chairman of your reservation) practice his speeches, the trauma of being bullied for having a “girly” voice, and then having singing lessons as an adult. Can you talk about your voice in relation to your poetry?

PICO: I can make my voice do pretty much anything, so I try and write to my strengths and affect emotion with my voice. When I write I’m very conscious of how it’s going to sound when it comes out of my mouth. I wouldn’t write anything that felt disingenuous to say. I’ve also always been so reverent to people’s voices; I loved Sister Act [1992] when I was growing up! I’ve just always felt that singing is the magic that I believe in. When I hear somebody sing, I’m like, if anatomically we’re all so similar, why doesn’t that come out of my body?

KENNY: Wait, as if you’re not a good singer?

PICO: I am a shower singer, and I will do karaoke! My mother sang in a church, my parents both sang at funerals in Kumeyaay country, and both my grandmothers played a bunch of instruments, so I’ve always been very close to singing and music. I always observed my parents, but from performing I’ve learned how to use that curiosity and reverence to develop my own voice as a tool and a weapon. I started doing vocal exercises and running along the water because that’s what I heard Beyoncé did. I also went for vocal runs—running and singing—and people would look at me very crazy.

KENNY: Is running part of your creative process?

PICO: For sure, I do 30 miles a week. I write full time, which means that I am basically always in my own head. Running reminds me that I have a body.

TOMMY PICO’S LATEST BOOK, JUNK (TIN HOUSE BOOKS), IS OUT MAY 8, 2018.