Three Artists Ponder the Future of Food at Magnus Nilsson’s Fäviken

Can the gut think? Is it possible to extract oil from lettuce? What would happen if we applied the tenets of brutalism to food—and why would we want to? These are just a few of the questions that came up earlier this fall when the artists Carsten Höller, Rirkrit Tiravanija, and Tobias Rehberger traveled to northern Sweden’s Jämtland province to visit MAGNUS NILSSON at his two-star Michelin restaurant, Fäviken. Located 200 miles south of the Arctic Circle, Fäviken is the 34-year-old chef’s ode to his wild environs—and the methods of food preparation required at that latitude. Nilsson cooks only with ingredients sourced from the restaurant’s 20,000-acre estate, with the exception of the beef that comes from a neighboring farm and the seafood caught off the nearby Norwegian coast.

All of the artists have made the pilgrimage to the restaurant before, booking months in advance to secure one of its 24 seats. Each is also known for producing works that explore how food and drink, and the spaces in which they are served, foster connections among people: Tiravanija hosts communal feasts of Thai food in galleries, once feeding tom kha soup to thousands of guests at Paris’s Grand Palais; Rehberger has designed dazzling geometric bars in New York and Venice; and the well-documented carnivore Höller once opened a part-Congolese, part-European art installation turned pop-up restaurant in London called the Double Club.

As a special treat for his friend Höller, who raises songbirds at his apartment in Stockholm, Nilsson prepared a nine-course meal with as many different species of bird. The fowl was seasoned only with salt.

———

MAGNUS NILSSON: I’d say that this scallop is almost brutalist.

CARSTEN HÖLLER: Why “almost”?

NILSSON: Because it has a bit of butter in it.

RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA: A touch.

HÖLLER: Could you do it without the butter?

NILSSON: Yes, but it’s a little difficult, because the scallop will stick to its own shell on the way to the dining room if you don’t smear the shell in butter.

TIRAVANIJA: So the grease is not for taste?

NILSSON: No, but hold on, they want me to look at something in the oven. I’ll be back in a second.

[Nilsson leaves the table]

TIRAVANIJA: If the butter is not for taste, then it’s only a cooking method. It doesn’t affect whether it’s brutalist. For example, if you have to throw an egg into a pan, you would need grease in the pan. But I would say that a fried egg is still a brutalist dish.

When Magnus Nilsson appeared on the first season of Netflix’s Chef’s Table, the epicurean Swede reminded the world that “farm-to-table” is so much more than a yuppie trend. Patrons from around the world wait months for a seat at the 35-year-old’s Fäviken restaurant, which is known for serving challenging delights such as moss, dried pig’s blood, and raw mussels at its compound deep in the Swedish hinterlands.

HÖLLER: But the grease, of course, is giving it taste.

TOBIAS REHBERGER: What if you extracted the grease out of the yolk of an egg, and then fried the egg in that grease?

HÖLLER: Then you would need more than one egg.

REHBERGER: Would that taste good?

HÖLLER: We don’t know, because we haven’t done it yet.

TIRAVANIJA: Imagine if you could make a salad that was salted by salt extracted from the leaves in that same salad.

[Nilsson returns]

HÖLLER: Magnus, we want to ask you something: If you had a salad, and you weren’t allowed to use anything else but the salad to dress the salad—

REHBERGER: No grease!

HÖLLER: No outside oil. How would you do it?

NILSSON: Can you use a whole plant?

HÖLLER: You can use a whole field to make one dressing if you want to.

REHBERGER: But it should only be one ingredient.

NILSSON: I think it’d be best done with either rapeseed or cabbage—any crucifer. You could make the salad, press the seeds into an oil, and then maybe make a juice out of the rest of it that you ferment into vinegar.

HÖLLER: But what about a leafy salad?

NILSSON: No, no, no. With a green salad there aren’t enough nutrients to have that amount of extractable oil.

A noted gourmand, the artist Rirkrit Tiravanija’s most famous works mobilize eating as a mode of social interaction, turning galleries and museums into banquet halls. These takeovers of public spaces have made the Buenos Aires–born, Thailand-, Ethiopia-, and Canada-raised artist one of the names most commonly associated with relational aesthetics.

HÖLLER: Do you feel like one-ingredient dishes give more freedom to the eater, or is this against the idea of cooking itself?

NILSSON: Not really. We present a lot of dishes that have very few things on the plate.

HÖLLER: That’s why I love it here!

NILSSON: Running a restaurant is very much about craft and giving people pleasure, but cooking is also my creative expression. However, this creative expression is very different from other creative expressions in that it inevitably becomes obsolete if it doesn’t give any pleasure.

HÖLLER: For example, if something in fine art is terrible, or very difficult, it can still be very interesting in a way that you enjoy.

NILSSON: Yes, people can be prepared.

HÖLLER: But in that same sense, why can’t you enjoy something that has a terrible taste?

TIRAVANIJA: Because that’s not good craft.

NILSSON: And I think cooking is closer to craft than art. For me, I’ve never felt an interest to conceptualize too far. I want to see people having a good time. However, on a long menu, you can do some dishes that are more thought-provoking and not immediately pleasing. But if you were to only serve those four or five dishes, the whole idea of the restaurant fails.

REHBERGER: Carsten, you say that one-ingredient dishes give more freedom to the eater. But is that what you really want as an eater? It’s not like if I want to watch TV that I suddenly want to make TV myself.

HÖLLER: No, but as an eater I’ve already had all the experiences that are available. I want something that hasn’t been done yet. So I think it’s very interesting to try to be dogmatic.

NILSSON: I think there’s something sadistic about that somehow. There are also so many single products that are full of complexity and contrast. For example, the whole birds for tonight have so much contrast on their own that they can be their own meal: teal, thrush, hazel hen, wood hen, pigeon, grouse, capercaillie, and then another one—

HÖLLER: Mallard?

NILSSON: Yes, and then?

REHBERGER: Blue jay.

NILSSON: Exactly.

TIRAVANIJA: You ate the whole thrush last time, because you’re a hardcore bird-eater.

REHBERGER: I have good teeth.

NILSSON: I get a huge amount of pleasure out of the process when I cook. With birds, I like to cook them over a fire so that you can touch them and understand the development of the flavors.

TIRAVANIJA: With sous vide, it takes too long for you to see that development.

The work of Tobias Rehberger, a medium-agnostic sculptor and Martin Kippenberger acolyte, has found the German native tricking out everything from sports cars and Japanese gardens to a naval steamship called the HMS President. In 2013, his razzle-dazzle spree took him into the world of hospitality when he re-created his favorite Frankfurt bar in New York’s Hôtel Americano.

NILSSON: But then I’ll also do something like age an apple for nine months.

TIRAVANIJA: That’s slow cooking!

HÖLLER: I remember we had this memorable evening where we went to your house, and you had this turbot that was, like, 10 days old. That was the first time I ever had aged fish.

TIRAVANIJA: Sashimi is aged as well.

NILSSON: With many fish, when you think about how it’s gotten to the market, you realize it’s been aged involuntarily. In the beginning, I was completely obsessed with having very, very fresh fish. But certain fish such as cod doesn’t taste like anything and has terrible texture when you eat it on the day it’s caught. A turbot that’s been handled the right way can keep for almost a month. As long as the meat is aired, it usually doesn’t go bad. For example, if you put a piece of beef on a rack in your fridge, it can sit there for months. If you wrap it—

HÖLLER: It rots.

NILSSON: Yes.

HÖLLER: There’s been research done about the incredible density of neurons in the gut, and the idea that the gut is like a second brain, or a thinking organism.

NILSSON: Really? I didn’t know that.

TIRAVANIJA: I feel like everybody experiences that. Sometimes, if I feel slightly depressed, I’ll take a shit and it’s much better. But that’s more on the level of feeling than thinking.

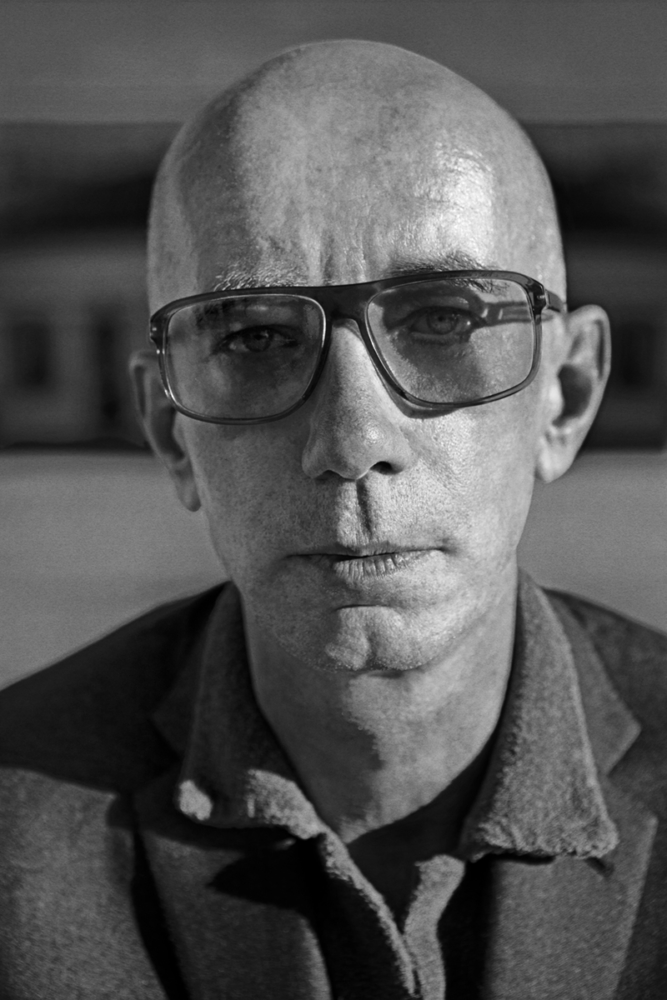

Carsten Höller

HÖLLER: I get depressed when I don’t eat nice food. Or when I’m on an airplane and they give me that shitty little bottle of wine.

NILSSON: I think the worst food is when people don’t deliver what they say they’re going to deliver. For example, I don’t have a problem with McDonald’s, because they deliver exactly what they claim to.

HÖLLER: Do you ever think about cooking with psychoactive ingredients?

NILSSON: That would be brutal!

HÖLLER: There’s this one Swedish mushroom—we have to look up what it’s called, but it’s basically toxic and you have to cook it twice and dry it. But there’s still a little bit of the toxin left when you eat it, so people say it gets you a bit high.

NILSSON: The toxin is water-soluble, so you have to dry it first so that the water content evaporates. It’s amazing: Up until 15 years ago, no one in Sweden knew that pine mushrooms grew up here. But then there was this group of Japanese tourists on a bus tour who went out of the bus to take a pee, and they found it. Excuse me, I have to go check on a torte.

[Nilsson leaves]

HÖLLER: Can we stop here? I can’t wait to eat.