CULTURE

The Photographer Theo Wenner Enters the NYPD Homicide Squad’s Inner Sanctum

Theo Wenner. Photo by Lily Gavin.

Spend enough time around police detectives, and your assumptions are likely to be both confirmed and subverted. Inquisitive and obtuse. Crafty and blunt. Suspicious of everybody and afraid of nobody. They wear an unflappable, seen-it-all look that is equal parts weapon and defense mechanism. The photographer Theo Wenner captured that look, and the moments that contribute to it, in Homicide, his new book of photographs chronicling a year spent riding along with the NYPD’s North Brooklyn Homicide squad. When asked if his project, which marks the first time that the NYPD has allowed a photographer to view the inner workings of the department, carried any larger political implications, Wenner had this to say: “It’s not a political statement… It’s just what happened, and you can come to your own conclusions.” It’s tempting to view Wenner’s work as a real-life episode of The Wire, a TV crime drama incarnate that exposes viewers to lurid scenes witnessed during nights on the job. Instead, the photographer accomplishes something else—through his fascination with details (a medical examiner’s mechanical pencil, an M&M wrapper), his work reveals just how eerie and otherworldly these moments can be. Here, Wenner reflects on a few of the images in Homicide, out this week.

———

Detective Thomas Handley rides the elevator en route to the scene of a double homicide.

THEO WENNER: I’ve always been really interested in this subject, maybe because it’s so much a part of American mythology. It’s like a Western, or baseball. I love the subculture and all of the unwritten codes of this world. I wanted to see what it looks like now. Does it actually exist like you think it does? The way they dress, the way they talk?

DAN MURPHY: There are several of your pictures that, if you told me they were taken in 1955, I would believe you.

WENNER: It’s completely true. It’s interesting because the detectives are kind of aware of it, the way they dress. It’s like a self-fulfilling prophesy almost, which is fascinating in its own right.

MURPHY: When you were conceiving of this project in 2016 and 2017, police were not having the best PR moment. Were you worried about how it would be received? Was it a motivating factor to cut into that narrative?

WENNER: I wasn’t worried about how it was going to be perceived initially. But in 2020, the conversation obviously became much more intense. After that, given how sensitive the subject matter was, obviously it crossed my mind. But it’s not a political statement. It’s photojournalism. It’s documentation of these detectives. It’s just what happened, and you can come to your own conclusions.

Detectives Alex Grandstaff and Mike Jimenez return to the scene of a homicide. A male allegedly attacked his girlfriend with an axe.

WENNER: These guys are like rockstars in the police department.

MURPHY: Like you said, policing is part of the American mythology. The police procedural is one of the most reliable television spots. But it’s always murder police. It’s about death, right? It’s about life and death.

WENNER: It’s the ultimate universal subject.

Dets. Thomas Handley and Matt Lamendola gather witness statements from neighbors who may have heard a shooting in the hallway.

WENNER: These guys are so intelligent and street-smart. It all starts with talking to people. Hearing things. Getting pointed in a direction. They can talk to anyone. Their feel and intuition is just incredible. It is such a deep knowledge of New York and the streets and talking to and reading people. An ear for conversation that’s unbelievable. When I first met them and went into the detective squad room, I could not believe they looked like they looked and talked like they talked, smoked cigars. It really is old New York—you don’t know what decade you’re in.

MURPHY: Are you a fan of Richard Price?

WENNER: I’m a huge fan of his work. I showed a lot of this project to Richard Price. He’s done ride-alongs with the police for years. He said, “Theo, you’re never going to forget your first homicide. You’re going to remember everything about it.” When I started this project is when the murder rate [in New York City] started to go up again. And then 2020-2021 were kind of off the charts.

A calendar outside of the lieutenant’s office shows the number of days since the last murder.

WENNER: There are certain photographs you know are good when you take them, and this calendar shot was one of them. Especially with the silhouette of the detective in the background. That detective, Mike Windsor, was like, “That’s my favorite photo in the book. Because you can’t see me.”

Christmas in the squad room: Detectives Handley (left) and Kenny Juart.

WENNER: It’s all about ball-busting, constantly, with these guys. From the moment they walk into the office to the moment they leave, it’s just a running dialogue of ball-busting.

MURPHY: That’s how you know they like you.

WENNER: Exactly, and if you can take it and give it back to them, you get a lot of respect from them. I was always myself. I never tried to fit in with them. And I think they respected that a lot. I gained their trust, they saw they could make fun of me, and then I just kind of disappeared into the background. Or tried to. The interesting thing was this has never been done before. A photographer’s never been allowed to photograph New York City detectives.

MURPHY: Really?

WENNER: My point is, there were no rules. There was no precedent to say “you can do this, you can’t do this.” So that’s what was so crazy about this. There were no guidelines.

MURPHY: A great thing for an artist.

WENNER: I know. I had to cut myself off with the project. I mean I knew I had what I needed, but knowing that any second something of so much consequence could happen, at any moment, on a daily basis, it’s a very hard thing to walk away from as a photographer.

The crime-scene unit processes a small stairwell leading to a building’s rooftop.

WENNER: The medical examiner in this photo came straight from a salsa lesson to a homicide. I remember she kept her pen shoved in the neckline of the dress she was wearing under her Tyvek white suit. You know, you have a certain way of photographing things, of seeing things. It’s not just that you’re photographing a person. The stuff around them says more than an actual picture of the person’s face. Especially with the detectives. It’s all the little things that add up to the subculture and traditions. It’s the way they wear their badge. Two cell phones in their hands at all times. All the little things that become so interesting, and those tell the story.

A male victim was killed in the building’s ground-floor hallway. Three other victims escaped up the stairs and survived.

WENNER: It was raining the night I took this photograph. Pouring rain. This was in a building referred to by the detectives as “the Smurf Houses.” I guess they’re quite dangerous, this row of buildings. I think quite a few homicides have happened there. Actually, two happened there when I was with them. Anyway they called them the Smurf Houses because they’re small. They’re not big towers. They’re two or three stories or something like that. I think a group of people were waiting for an Uber and a guy or guys came up and shot at the group. Multiple people died. There’s another photo in the book with a bunch of orange cones covering shell casings. That’s from that scene. So you can see the path of how the shooter started firing just by those cones. You can see that he’s moving into the hallway. I think one person ran up the stairs. You can see the blood on the stairs. You can see the bullet holes in the wall.

MURPHY: What was that like for you personally? On an emotional level? The first time, the first few times. Coming in. A dead body.

WENNER: I remember every single detail. I don’t know what it is about an event like that, you remember the day perfectly. I had never seen a dead body before, and I’m about to walk into a murder scene. So obviously I was very nervous about how I would react. But you’re with them, and they’re such pros. It’s a cliché to say, but it really does set a tone. And you’re watching them watch the crime scene, and their steadiness sets a tone. Having a camera in front of your face gives you a little barrier, but it was pretty disturbing, obviously. Everything’s in a split second, suspended time. You’re staring at the person’s face and it’s like they got caught mid-sentence, the eyes open and looking off into wherever, there’s like a yellow M&Ms wrapper next to the victim. Those little details take on so much significance. It’s almost like they’re vibrating—everything becomes so consequential when it’s connected to a murder. The little objects around them.

MURPHY: You studied with Stephen Shore at Bard. He’s known for focusing on everyday objects and generating a lot of work from otherwise banal or quotidian subjects. Was that something you learned from him or was that just naturally how you came to it? Like the photo of the pencil in the medical examiner’s hand on a door jamb.

WENNER: It’s not one single thing that Shore imparts on you. You start to realize the importance of objects. It’s like I said, something banal can be more revealing than taking someone’s portrait. If you take someone’s portrait, you’re not necessarily capturing their soul. You’re capturing how they want to project themselves to you. Which is interesting in its own right. But objects are unbiased, you know?

MURPHY: Unaffected.

WENNER: Exactly.

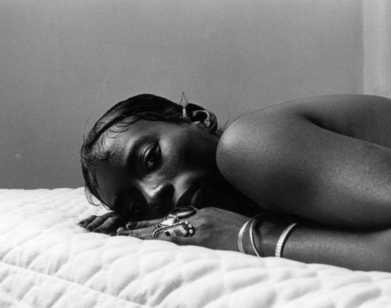

A man suspected of killing his girlfriend with an axe awaits interrogation by two detectives.

MURPHY: Most people would think that the subject is dark that you’d shoot it in black and white, but you chose color.

WENNER: My initial instinct was to shoot in black and white. But then I thought, “You never see this in color. What does this world look like now? I want to see the colors.” The colors are such a strong thread throughout the book. There’s the precinct green. The interrogation room is this bizarre green. These colors are so specific. Someone chose that color.

A detective stands over a spent bullet casing and blood droplet leading toward the front door.

WENNER: For this one, I was standing right next to the detective, and I think he had his flashlight out. The shine, the high-gloss leather shoes, the bullet, and the blood—it was a a moment that really struck me as the book’s cover image. I love the tightness of the photo. Somehow it’s the whole atmosphere of their world in one moment. For me at least.

Dan Murphy is a writer and professional investigator. He has an MFA from NYU and is working on his first novel.