Shannon Moroney, Clear as Glass

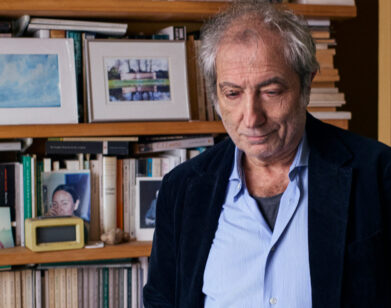

ABOVE: SHANNON MORONEY. IMAGE COURTESY OF ANKA CZUDEC

In Shannon Moroney’s memoir Through The Glass (Gallery Books), the author bravely recounts her husband’s violent crimes and how they shattered her marriage. Jason told Shannon he had committed a murder as a teenager, a horrible young mistake he had done jail time for and regretted every day. Shannon was a counselor and natural healer, and, though Jason’s past certainly scared her, she loves him, believes in second chances.

Then, a month into their marriage, a police officer knocks on Shannon’s hotel room door while she is at a work conference. Her husband Jason has confessed to kidnapping and raping two young women. With candor and courage, Moroney writes of her heartbreaking journey through violence, confessing just how hard it was to come out stronger on the other side. Now a restorative justice advocate, Shannon speaks to the ripple effects of crime: how one act can tear apart so many lives. We spoke with Shannon about battling with the big issues: love, betrayal, trust, justice, and hope.

ROYAL YOUNG: How well can you really know the people you love?

SHANNON MORONEY: The very scary thing is that all of us have free will and the capability of betraying one another’s trust. Most of the time we do it in small ways, or we can do it in colossal ways, like what Jason did. There aren’t any guarantees. Some people choose to live in fear of that. One of the choices for myself, since Jason, is—people say to me, “How could you trust again?” But I think, how could I not? It’s been painful to be so judged for trusting someone.

YOUNG: Why do you think that happens?

MORONEY: Jason’s actions were extremely scary, and when something like that happens, everyone wants to get far away from it. For some, that meant getting far away from me.

YOUNG: What would people say about you?

MORONEY: Oh, “I’m not like Shannon, I’m not naïve, I would never be blind to all that, I would never trust anybody, I would never have given him a second chance, I would have gotten up from that table and walked away.” They want to be able to say that to feel safe. But it ends up causing more hurt.

YOUNG: Do you think when people judge you, it’s more about a fear of themselves? It’s so scary to feel like anyone you love can betray you. They want to believe they would have some safety in place.

MORONEY: I think that’s very insightful. In a crisis like this, you find out where people are in their lives. I understand that fear and reaction, I’m just hurt by it. I’m sorry I got to be in the line of fire for something I didn’t do. Jails protect society from dangerous people, but they also protect those people from facing up to the consequences of their actions. They leave behind other people, usually family members, to do that for them. I think we can do better than that. I think jails and prisons need to involve a level of accountability, especially with someone like Jason.

YOUNG: What would that look like?

MORONEY: To me, that looks more like restorative justice. Instead of who was harmed, who did it, and how do they get punished, we’re looking at—what are their needs?

YOUNG: It seems like understanding human relationships and how they impact other people has been a big part of your life.

MORONEY: Yeah, it’s always been part of my life. There was a brief time when I was very young when I really wanted to be a cruise director, like Julie McCoy on Love Boat, but then I always knew I wanted to be part of helping people as a counselor. But I never imagined I would work with justice, certainly never that I would advocate for the treatment of sex offenders.

YOUNG: What do you think it is about sharing our stories that is so healing?

MORONEY: I think it’s the alleviation of stigma, breaking free from isolation and for broader dialogue on justice, we have to hear from more and more voices. Everything related to crime and justice is layered and gray, it’s not the black-and-white bumper-sticker justice we often see from government.

YOUNG: It also seems like you discovered when a crime happens, you’re dealing with so many different people. It’s not just about this person hurt that person and the person who did the hurting is going to be sent away. There are circles going out and out of people that this impacts.

MORONEY: Exactly. I always talk about the ripple effects of crime. Stranger crime makes up only a small percentage of crime; it’s very unusual. Most crime is committed within families. But I just saw this ripple effect go out and out and out and I longed for something to help mitigate. Even now, the storeowner, where the crime took place, is being sued by the victims. And I just think of this man who was betrayed by his employee, by Jason, is suffering. It’s another victim, and it’s still going seven years later. Now, when I watch television and see the typical picture of a seedy person who’s committed a crime I look beyond it and think: What about their family? Who knew them? I don’t get to judge them anymore. We cannot undo a person’s actions, I can never undo what Jason did, but we can try to stop that ripple effect. We can come together instead of running away from the hurt.

THROUGH THE GLASS IS OUT NOW.