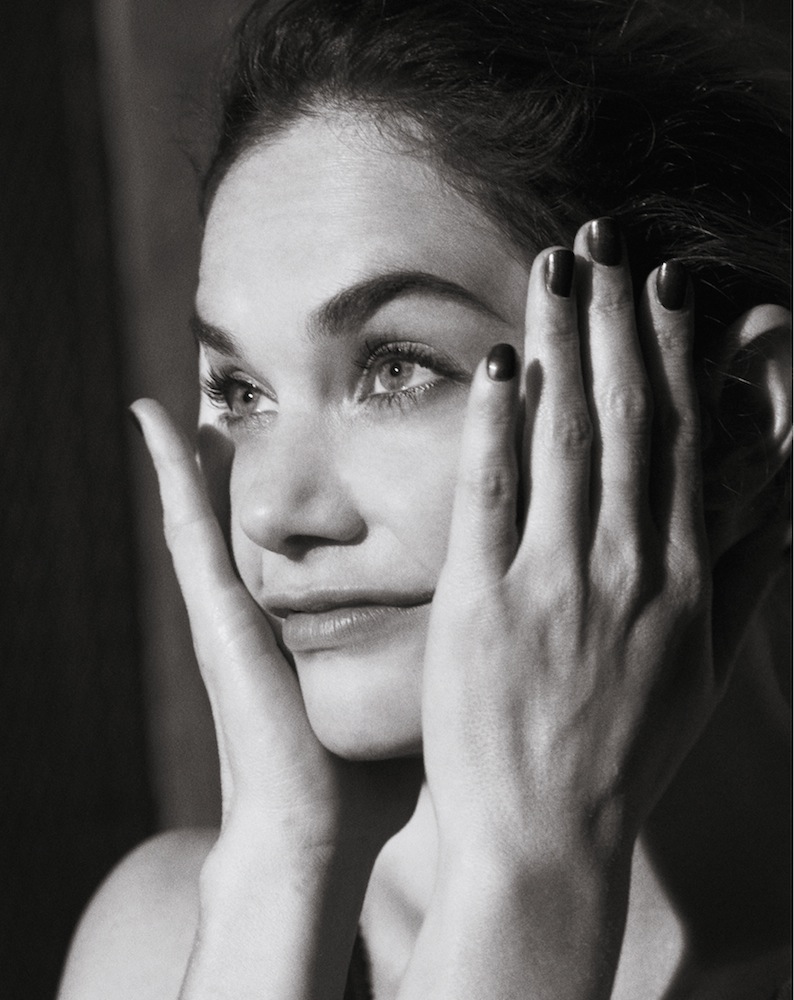

Ruth Wilson

Ruth Wilson knows her way around a maddening heroine. Witness her absorbing command of the psychopathic murderer Alice Morgan, an adversary and confidant of Idris Elba’s titular detective on the BBC crime procedural Luther, and then, too, her role in the steamy he-said-she-said Showtime drama The Affair, for which she nabbed a Golden Globe last year.

Not that this command for playing beguiling and beguiled characters in premium drama is entirely new. Since her auspicious early performance as Jane Eyre in the BBC’s 2006 television adaptation of the Charlotte Brontë classic, the British actress has amassed a body of work steeped in prestige. She’s earned two Olivier Awards for her time on the London stage (in the title role of the Donmar Warehouse’s 2011 production of Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie, alongside Jude Law, and as Stella in the Donmar’s restaging of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, in 2009) and a Tony nomination for the Broadway run of the romance Constellations opposite Jake Gyllenhaal, where she played a socially awkward quantum physicist. Breakthrough film roles came in The Lone Ranger (2013), across from Johnny Depp and Armie Hammer, in Suite Française (2015), and in Joe Wright‘s Anna Karenina (2012).

This month Wilson, 34, returns as Alison Bailey, a conflicted waitress turned restaurateur caught between her ex-husband (Joshua Jackson) and her flame and now husband (The Wire‘s Dominic West) for The Affair‘s third season. But as she tells her friend, the writer, director, and performer John Cameron Mitchell, much more is to come. She’s gearing up for the December debut of a modern version of Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, in which she takes on the revolutionary part, directed by Ivo van Hove, at the National Theatre, and she’s awaiting the release of Clio Barnard’s Dark River and Mitchell’s How to Talk to Girls at Parties, in which she stars as a cannibalistic alien with a penchant for latex. Mitchell called up Wilson from San Francisco in September to talk about her menagerie of leading ladies, playing tough, and getting your hands dirty.

JOHN CAMERON MITCHELL: You’re the hardest working lady in show biz. How many things have you done on your hiatus from The Affair?

RUTH WILSON: Three films.

MITCHELL: Jesus Christ.

WILSON: I’ll sleep when I’m dead.

MITCHELL: Oh, God. Or sleep when you’re my age.

WILSON: Where are you?

MITCHELL: I’m in San Francisco. I just got back from a Radical Faerie community—spelled F-A-E-R-I-E, like The Faerie Queene—which is a queer “intentional community.” It’s like a commune.

WILSON: Are you just popping in and observing?

MITCHELL: I was the first artist-in-residence at this new community. And I feel like a goddamn hippie, I tell you.

WILSON: So, did you have your space and your time? You had your animals. Did you write anything?

MITCHELL: I did a bit of writing. It’s a bit of autobiographical stuff, which is driving me crazy. I notice that you had directed some. Are you going to be doing more directing, and even writing?

WILSON: I don’t know about writing. It’s quite lonely. You have to have a lot of patience with yourself. I don’t know if I could do that. But I’d love to direct again. I had a chance to be involved in the creative process of everything, not just the acting, but what the lights were going to do, what the sound design was going to be like, the casting, watching actors develop and grow and—

MITCHELL: Stumble.

WILSON: And stumble. [laughs]

MITCHELL: It’s fun to help them.

WILSON: And them asking you what to do, and you’re like, “I don’t know.” [laughs]

MITCHELL: I love when a director says, “I don’t know.”

WILSON: I’m not very good at lying, so I can’t bullshit that.

MITCHELL: And yet you’re good at acting, which is kind of lying.

WILSON: Massive lying. [both laugh] True. If someone else gives me words, okay.

MITCHELL: Did you lie as a kid?

WILSON: I’m crap at lying. I go bright red.

MITCHELL: Oh really?

WILSON: I’ve got friends who are so good at getting away with things, like going up to the desk to get upgraded on a plane, for example. I haven’t got any of that kind of confidence in those situations. I look so awkward. I act awkward. I’m really apologetic. I fail to get anything that way. I’m crap at pretending to be something I’m not when I’m in my real life.

MITCHELL: I know a director—name that will not pass these lips—who I saw from a distance in an airport, take out a portable blind person’s stick and use it to get on the plane faster.

WILSON: No. [laughs] Have you seen him since?

MITCHELL: Yes. But I didn’t know what to say. It was so horrifying.

WILSON: Did he wear sunglasses as well?

MITCHELL: Yes.

WILSON: He did the whole thing. I went recently to Toronto. My friend who came with me pretended she was pregnant so she could get a seat.

MITCHELL: Did she put something under her—

WILSON: No, she just … pretended that she was pregnant.

MITCHELL: She was like, “It’s my first trimester”?

WILSON: Exactly. [laughs] I admire the brazen qualities in people.

MITCHELL: I do too.

WILSON: Sometimes I feel like I wish I could be more like that.

MITCHELL: So this film that was at Toronto, is it a hoot and a half? Tell us what it’s called.

WILSON: It’s I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House. I read it and it was very odd and poetic and had a huge narrative, a sort of monologue voiceover. It felt like an old-fashioned ghost story. I really enjoyed working on it because Oz [director Osgood Perkins] is very free and very playful. We had loads of time from Netflix as well. He had six weeks to do a film that in other studios and elsewhere would be shot in three.

MITCHELL: Wow.

WILSON: So the DP had loads of time to light, and we had time to play. My character is a bit weird. She’s like a Cinderella character that was trapped in a house—she’d talk to the moths and to the TV.

MITCHELL: Clio Barnard’s film [Dark River], which you did this year, too, she’s known for her naturalism.

WILSON: That was really interesting, because I was quite scared about working with Clio, because she has been aligned with Ken Loach.

MITCHELL: British miserablism. That’s a term I’ve heard that’s very, very reductive. I think you can use naturalism in so many ways. But people are like, “Oh, if it’s a little tough, it’s miserable.” From Lynne Ramsay to Ken Loach to Andrea Arnold to Clio. Lately, it’s been more women who’ve been getting into naturalism. I love British female directors lately.

WILSON: She’s such an amazing woman. I haven’t talked to you about this, but it was a brutal filming experience. I had to be a sheep shearer. So I had to learn to shear sheep and castrate lambs and gut rabbits and smoke rats out of a building. Every day there was a huge physical feat to overcome. It was also set up in Yorkshire, and there are hardly any lines or any words. It was all very atmospheric and tense: fighting men and sheep every day. When I read it, it was like the female The Revenant. I don’t really want to see sheep ever again. There’s actually a fake sheep around the corner from me in a shop. I’m tempted to go and shear it. [both laugh]

MITCHELL: Well, last night I had rabbits at this faerie camp that I had petted earlier in the day; I had them for dinner.

WILSON: Did you kill it?

MITCHELL: I didn’t. And I was afraid to be there when they did. But they do it very humanely. These aren’t the vegan hippies. These are people who have animals, and they treat them really well, and they eat them sometimes.

WILSON: I come from the south, so you’re useless and you’re a bit pathetic. That’s the first thing that the northerners think of you. You’re also from the city, so you are used to having your cappuccinos and your luxuries and getting your chicken from a plastic packet. So you go up there and you’re, “Oh, God, I’ve got to touch these things. I’ve got to do things to them.” But then you see how they do it. It’s amazing, actually. It’s huge love and respect for the land. There’s a farmer that I worked with, a sheep farmer, and they lose sheep quite often. He would hate ever having to kill a sheep if it wasn’t going to slaughter.

MITCHELL: Nature is a series of murders. It’s like a season of Luther.

WILSON: You’re very good at segues.

MITCHELL: Well, you know, I was seguing from each one of the gems on the nexus of your career. [Wilson laughs] I was just looking at you looking like a child on Luther.

WILSON: I know, it’s been a long time.

MITCHELL: You were so young. And you were so psychopathic. [Wilson laughs] I always wonder about psychopaths, just because they have no empathy, does that necessarily mean they enjoy being cruel? Because we all know people who seem to have no empathy that we work with; they’re not necessarily cruel. Did you study the psychopath?

WILSON: Yeah, I did. I watched loads of films, and there’s obviously references to Hannibal Lecter and various things in there. I got insight with a book that I read by John Gray called Straw Dogs. He started describing humans as viruses. I was kind of overwhelmed by the idea that we are just balls of energy and that we have imposed terms on feelings.

MITCHELL: Doesn’t psychopath mean you also manipulate people? Isn’t that part of the definition?

WILSON: That’s the thing. How I got inside that head of that character was to go: “Well, if she is in the position where she is not constrained by these terms and the guilt, then she can stand above it and manipulate people when she sees that they are being constrained by those terms. She can manipulate most people that are living by what society told them to be.”

MITCHELL: How do you explain Trump?

WILSON: Don’t ask me. I don’t know what that is.

MITCHELL: [laughs] It’s weird!

WILSON: That’s also got to be coming out of what society is at the moment that he gets away with whatever he says.

MITCHELL: It seems like there’d be no Trump without the internet, first of all. He’s a tweeter, which is basically just a bullhorn.

WILSON: And for some reason, he’s what people seem to be wanting. It’s frightening.

MITCHELL: They want entertainment. Doesn’t Brexit have a certain energy of, like, let’s shatter what is?

WILSON: Brexit for me was really interesting because I was in the heart of Yorkshire, which is a “leave” area. It was quite odd actually, a real deep sense of unease. You felt very odd for your country. You have lots of people that are angry. It’s a very physical and public stand that these people are making. Leaving Europe in my mind wasn’t the best thing; it’s not the best way of having that political voice. But that’s the only voice they could have. People turned out in their droves to vote, more than for prime minister. So it was huge and very divisive.

MITCHELL: I’m afraid for this November here that people’s frustration is simply to hand the keys to someone who doesn’t drive and also is smashing up the car. I’m going to go work for Hillary. I’m going to go wherever I’m needed.

WILSON: I also think the environment is possibly our most worrying thing at the moment, so I think mountaintops are the place to live.

MITCHELL: Well, I’m going back to that Radical Faerie community.

WILSON: I might come with you.

MITCHELL: You’re welcome. You can be an alpaca intern. So you’re in the middle of shooting The Affair?

WILSON: I’ve got another two months or something left.

MITCHELL: I was just watching clips. You are like a crazy person in that. You’re so realistic. I love it.

WILSON: Oh, shut up.

MITCHELL: You are.

WILSON: She keeps getting confused about which man she loves and her children. She has a dead child and a new one, and it’s all very confusing for her. It’s quite intense.

MITCHELL: Do you know from episode to episode where the character is going? Or do you prefer not to?

WILSON: Well, I used to want to know.

MITCHELL: Because you’re from the theater.

WILSON: I’m from the theater, darling. I want to know what happens at the end. Also in Britain, we haven’t got enough money to make these long-running shows. We always do little mini ones. You have more control as an actor over what you want to do with it. On these you drive yourself mad trying to know what’s going to happen, because the writers don’t.

MITCHELL: You play the moment.

WILSON: By episode eight, season 18, I hope that Dominic [West] and I reveal that actually we’re both British. [both laugh] That’s why we’ve always been sort of connected.

MITCHELL: Or is it a dream of his character in The Wire. Or your character in Luther.

WILSON: We were just about to talk about the most important thing.

MITCHELL: Our film, How to Talk to Girls at Parties. Punks fall in love with aliens. It’s funny. You were so patient. Some days you were a glorified extra in a rubber suit. And I was like, “Oh, my God, Dame Ruth Wilson. She can’t pee.”

WILSON: [laughs] I was so impressed with you, John. I had to read the script three times to vaguely understand what was going on. When I read scripts like that, I go, “Okay, this is something so wild and brilliant I want to be part of it, because it’s like nothing else I’ve read.” I’ve still got the shoes.

MITCHELL: With the heels in the shape of butt plugs, by Dame Sandy Powell, our brilliant costume designer, who’s bringing latex back.

WILSON: I have to say I think it was possibly my favorite outfit I’ve ever worn.

MITCHELL: And it fit you like a rubber glove. You’re so fit. We met at physical therapy. We were both being beaten down by the physical demands of Broadway.

WILSON: I still go to Natalie to get my massage.

MITCHELL: Did she stick you with long needles?

WILSON: Yup, dry needling into my jaw. She was great. She said she had to massage Beyoncé’s feet all the time.

MITCHELL: She’s a master Beyoncé massager, Beyoncé whisperer. But we loved it when she cracked us up. And then I was like, “Want to be in a movie?” And you’re like, “Yeah.” It was pretty quick, right?

WILSON: It was such a huge cast and crew and lots of young people. It’s this coming-of-age story with these kids, and you’ve got all of them, the punks and the aliens, all on site. Every time coming on set, it felt like there was a wild party going on. It was brilliant.

MITCHELL: I spent a lot of time with making sure everyone felt wanted.

WILSON: Was that exhausting?

MITCHELL: It’s a little exhausting. I had my trusty assistant, Bryan [Weller], who would take me home, turn on Empire, give me an Ambien, and I would start drooling before the credits.

WILSON: [laughs] Oh, I love it.

MITCHELL: He was also helping find aliens and punks. I ran out of people and had to get some on Grindr … then toss them in the grinder. [Wilson laughs] You’re going to love yourself in this. I don’t know if you hate to watch yourself? Some actors really hate it. But you might crack yourself up. Are we going to do some more shtick together?

WILSON: Can we? I really want to. There was one day when I came in and went, “John, help me. What am I doing?”

MITCHELL: [laughs] “What am I doing here? What kind of a movie is this?”

WILSON: We sat for about ten minutes chatting about my deep loneliness in my character.

MITCHELL: As an alien who ate her children. And that improv you did with Nicole Kidman, who plays the punk queen—you’re the alien queen—that improv ended up in the movie. It’s a ’70s kind of movie. I hope the kids like it.

WILSON: I love it. You just have to probably smoke a bit of something.

MITCHELL: Hedda Gabler is going to be your next stage foray in December at the National Theatre, which I am coming to see, because that play can be a laugh riot, too. Talk to [director] Ivo [van Hove]. You’re going to pump some of those jokes.

WILSON: I think she’s wicked.

MITCHELL: Is she a protofeminist?

WILSON: I don’t know. When it was written, definitely. But I think it’s a humanist thing as well. It’s the idea of the choice over life and death. That’s a massive human condition to question that and to know that that is the one thing that you can have control over. It’ll always be played like Hamlet; he’s questioning whether they choose to exist or not. I think, because it was set in that time, for a woman to be questioning those things, it was unheard of.

MITCHELL: There’s so much that’s really revolutionary in Ibsen’s time. A Doll’s House and Hedda Gabler alone were just explosions of modern theater in that they were dealing with these very delicate subjects of women shattering social mores. Ibsen, Chekhov, Shakespeare, and Beckett to me are the most revolutionary.

WILSON: I agree. Even now, for women to be contemplating the act of ending their life is considered horrific because they are the giver of life. They’re seen in a patriarchal society as the one who offers life and has to nurture a child and have a child within them. That’s your only role. So to not want children or not be considerate of them is a very unwomanly thing to be, from a certain point of view.

MITCHELL: Oh, my God, it’s obscene. I’ve been reading this great book called Deformed Discourse about the things that seemed monstrous in art in the Middle Ages and to do with religion.

WILSON: I feel like male patriarchy generally has been about repressing female sexuality because it’s “scary.”

MITCHELL: Yeah, or all sexuality. Have you seen Antichrist [2009]? My God. It keeps popping up, of course. And we periodically run into a Bill Cosby allegation and you go, “Wow.” Being a queer person, I can see there’s a measurable effect of things that got better.

WILSON: Is it the fall of the white man?

MITCHELL: I think it’s the fall of people who felt stability and felt a power that they didn’t realize was actually kind of accidental. It was unconscious; it came with being white and heterosexual and having some money and following the rules. When that doesn’t work as well as it does, the first reaction from many people is anger and blame: “An immigrant’s getting my job. A queer person is getting special rights.” They’re equalized as the other. It’s so strange. Kids’ literature now is dystopian, you know, The Hunger Games.

WILSON: “It’s the end of the world.” You do get the sense that everyone is isolating, aren’t they? I feel like everyone’s starting to isolate, and that proves itself in a big context like Brexit, and Trump potentially, and putting walls up and stopping people coming in.

MITCHELL: That way lies madness if you really feel alone.

WILSON: We’ll always have art, darling.

MITCHELL: I’m turning everything off. I’m going to go work with the alpacas.

WILSON: I think you should. Go and shave them. Go to them. Get back and stop talking to me.

MITCHELL: I’m turning off my phone and throwing out my computer. I’ll tell you where you can find me. You’ll have to drive there.

WILSON: Well, write me a letter. Write me an old-school letter.

MITCHELL: I’ll write you on a sheep’s bladder, dried out.

WILSON: Don’t worry, the postal service is so crap it will never arrive. [laughs] You’ll have to walk it to me.

JOHN CAMERON MITCHELL IS AN ACTOR, WRITER, AND DIRECTOR OF HEDWIG AND THE ANGRY INCH, SHORTBUS, AND RABBIT HOLE.