Richard Lewis

The car from hell, the bar mitzvah from hell. I’m credited with popularizing that phrase.Richard Lewis.

Richard Lewis’s 2000 memoir, The Other Great Depression, is a veritable chronicle of one man’s lifelong quest to contend with seemingly endless pain and suffering. The book details everything from the lack of love that Lewis felt as a child to his difficult rise through the ranks of stand-up comedy, his crippling obsessive compulsions, the harrowing extent of his commitment-phobia, and his descent into alcoholism and addiction-and it does so in the funniest way imaginable. Of course, today, at 61, Lewis is three-years married and more than a decade sober. But he still has plenty to be neurotic about: There’s the recent paperback reissue of The Other Great Depression; there’s his ongoing Misery Loves Company Stand-Up Tour; there’s the return of the HBO series Curb Your Enthusiasm, on which he plays himself (minus a kidney); and then there’s life in general.

KATE SIMON: I’ve been reading your book, The Other Great Depression, and it’s just been—

RICHARD LEWIS: A depressing ride, huh?

KS: No, it’s been absolutely . . .

RL: Why are you weeping openly now?

KS: I’ve been really inspired by it. One of the things that I found interesting was how you became close friends with Buster Keaton’s widow, Eleanor, who was almost 29 years older than you. You talk about all these older people in the book, like her and Sally Marr and Phyllis Diller and . . .

RL: Jonathan Winters.

KS: How is it that you have the inclination for these elders?

RL: My father died before I was a comedian and my mother and I didn’t get along-she didn’t understand my work, although I think she was sometimes proud behind my back. So I didn’t get the kind of nurturing you’d expect from a mother. In the last decade, unbeknownst to me, I found out that Phyllis Diller was a huge fan of mine. She wrote me a letter and then we became great friends. To have a woman in her nineties who is a renaissance woman—she’s a painter, a pianist, not to mention one of the most iconic stand-ups of all time-understand me . . . We came from the same tree of darkness. Likewise, Jonathan Winters. He’s 82 years old-nearly 50 years sober. He’s had two nervous breakdowns and still talks about his family, how his parents didn’t respect him. He is also the most spectacularly funny human being I’ve ever known.

KS: What is it about Jonathan Winters that makes him the best?

RL: Well, I have to say Richard Pryor was arguably the greatest stand-up ever, and Lenny Bruce was maybe the most important, but Jonathan Winters is so explosively spontaneous. He can riff for hours, and make social and political points using characters. It’s almost tragic for me that he never really did much stand-up because he was way over everybody’s head-he was too hip for the world. As for Eleanor Keaton . . . I was in London in ’69 for about 14 days, and I stumbled onto a Buster Keaton festival. They had found all of these lost Buster Keaton films in the shed of James Mason’s house in Beverly Hills [which had previously been owned by Keaton], and this wonderful guy had gotten them all remastered. So at the festival, I basically saw all of Keaton’s work. I fell so in love with him. I was still in college at the time and I’d never seen anybody like him before. Eleanor must have been in her early twenties when Buster married her. She was a gorgeous, young actress-dancer and he was an alcoholic. But with Eleanor, Buster was okay with it. She helped him live a great last 20-something years of his life. She took him to all these festivals-he had no idea that he was so revered. And, luckily, because these lost films were found, he became an icon. After I became a comedian, I did this A&E documentary on Buster, and I met her at the wrap party. She lived in the Valley, so I called her from Hollywood and said, “Listen, maybe we could go to the Beverly Hills Hotel. It’s right near where Buster used to live and it’s sort of symbolic. Or, if you want to just go to a little local joint in the Valley . . .” She was a really tough cookie. She said, “No! You said the Beverly Hills Hotel and that’s where I want to go.” So I went to the general manager of the hotel and said, “I am bringing you Buster Keaton’s widow. I want you to treat her like a queen.” And man, they treated her like royalty-they brought cakes and gifts. It was one of the nicest nights of my life.

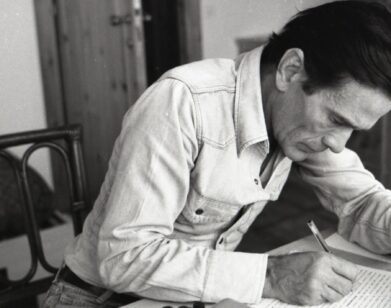

KS: You like to write in hotel lobbies. Why is that?

RL: I’m a New Yorker, born in Brooklyn, raised in Jersey. But as much as I might taunt Los Angeles, I’m in heaven living near Charlie Chaplin’s studio, and where Keaton shot his films, and Laurel Canyon, where everybody lived in the ’60s. So the hotels where I go, like the Chateau [Marmont], have great history. Plus, I get distracted in my own home, so I like to go to four or five of my favorite haunts where I used to drink heavily and sit there and have cappuccinos and Diet Cokes for hours. I go to the bathroom and come back, and there are 300,000 lemons and 4 million diet sweeteners . . . What I order is sort of nutty, but I tip well, so they don’t mind.

KS: You told me that you have a view of all of your doctors’ offices from your house. Is that true?

RL: Well, from my toilet on the third floor, I can see Beverly Hills, so I can see all of my doctors and where most of my ex-girlfriends live. If anyone wants to come get me, I have an alarm system that would make James Bond jealous. But I’m no more than 8-15 minutes from any doctor.

KS: I’ve got the same thing. You can never have too many doctors. So have you ever been unfaithful to your therapist—that is, had two at the same time?

RL: I did, tragically, when I started. I’m not sure how it happened, but when I was young and my dad died, I had no money, so a friend of mine who was a hospital administrator got me into therapy for a dollar an hour. I had an audition and I got in real easy—it was my best audition. The therapist was an intern. At the same time, I was also going to a group therapy that was based on Alfred Adler-he was the father of the inferiority complex, so it was basically a group of whining people. So I had this Freudian woman from India who I was seeing on my own, and then I had a Jewish woman who ran the group therapy. But I was so twisted, I don’t know how I convinced the intern to call the other therapist, but she did and they basically fought over me. I wound up going to the group, though, because it was nicer to be with company.

KS: I’m going to change topics here for a second. In your book, you talk about Jimi Hendrix, and how hearing “Purple Haze” for the first time just split you open like an atom. There’s a rhythm to the ways you perform that’s very musical.

RL: Most comedians who have lasted have a rhythm. Hendrix, obviously, wasn’t a comedian, but if someone could hit a note like he could, so down deep, I thought, Whatever I do in life, I’m going to try to go for that note. That’s how I felt when I heard John Lennon’s first solo album. I just felt like this guy was opening up his guts in a way that I had never heard before.

KS: So do you think that performers throw themselves into performing to run away from intimacy?

RL: It sounds clichéd, but I had such a horrific relationship with my mother . . . My shrink once said that I was an affection junkie more than a sex addict, that I needed to be loved by as many different women as possible to fill up the hole.

KS: Do you have any interests that no one would guess you have? I know that you’re somewhat of a pack rat.

RL: Well, I’m obsessive-compulsive. For example, I can watch John Cassavetes’s films over and over again. When I used to date women much younger than me, I would put them through training periods—”This is Ingmar Bergman week,” “This is Stanley Kubrick week.” It was very controlling, because they had to enjoy what I enjoyed. I see now how foolish and crazy and narcissistic it was. I like dark films. There’s a French film called The Mother and the Whore [1973]. It came out about a year after Last Tango in Paris [1972], which blew my mind and frightened me because it’s all about fear of intimacy. When I watch Marlon Brando in that movie now and I realize that I’m so much older now than he was when he was in it . . . Even though I got married, I still have . . . you know, those shadows followed me, those intimacy problems. The Mother and the Whore, though, was directed by Jean Eustache. He was this guy who came after the French New Wave and who wound up committing suicide. Jean-Pierre Léaud, who was one of my favorite actors, is in the movie. So I come home one night and I’m watching this film and I’m saying, “God, it looks like a [Bernardo] Bertolucci movie. It’s so dark. But I’ve never seen Jean-Pierre in a movie like this.” And it went on and on. It’s a masterpiece. It’s the greatest film I’ve ever seen on the Madonna-whore complex. So I do obsess over these films—I watch them over and over because, I guess, I sort of feel less alone and less crazy when I see some of these works of darkness.

KS: You talk about David Brenner in your book. Tell me about what his friendship means to you and how it is that he has affected you.

RL: I met David Brenner when I was in my twenties. He was already a star—he’d played Vegas, done The Tonight Show. But we hit it off immediately. I wasn’t that close to my family, so David became like an older brother to me instantaneously. Here’s someone who has consistently been one guy I can probably say I trust more than anyone in the world-other than my wife. This guy would watch my back, and I would his. From a showbiz point of view, he always told me what to do and what not to do because he had already done it. He gave me tips all the time, and I followed them. He told me when I was ready to audition for The Tonight Show. He told me when I was ready to go on tour with big acts. He helped me get gigs. He helped me get on The Tonight Show. And he was very, very adamant with me about getting into recovery, because he thought I was going to die. This guy is family to me. I can’t love a guy any more than I love this guy and still feel heterosexual.

KS: Explain why you call yourself the Prince of Pain.

RL: Well, I don’t think I ever called myself the Prince of Pain. I think it might have been written that way and then it stuck-it was in magazine articles. I don’t come out and say, “Hi, I’m the Prince of Pain.” But the truth of the matter is that whatever gift I have as a comedian, most of it was in the phrase “from hell,” which is now in The Yale Book of Quotations.

KS: The whatsit from hell?

RL: The anything from hell-the date from hell, the car from hell, the bar mitzvah from hell. I’m credited with popularizing that phrase because I felt victimized by everything. I used to say onstage, “I just came from a family reunion from hell . . .” Anyway, the truth of the matter is that when I got sober and took a little bit of a look in the mirror, it opened up a Pandora’s box of material. Even though there were some women from hell and relatives from hell, I, in turn, was a date from hell or an uncle from hell or a brother from hell. I was able to turn the lens on me, and it opened up thousands of premises that I could use to just rip myself to shreds. The truth is that I realized that I have a lot of defects. And even though I don’t drink and do those drugs anymore, if I don’t work on my defects, it’s sort of an empty sobriety to me. So I do really try to become a better man a day at a time. I think I’ve done that. I’m still nuts, but I’m a better guy-and that wasn’t the case for quite a while. So it wasn’t always the date from hell. It was me. That’s a big turnaround, by the way.

KS: Tell me about Larry David.

RL: What can I say? We met at camp when we were 12 and despised one another. Later, when I had been a comedian about a year, just making a name for myself in New York, I saw Larry go on and he was sensational. Larry was an unbelievable stand-up, a comic’s comic. But unfortunately, he would storm off the stage all the time because he just couldn’t tolerate people talking.

KS: You mean when he was doing stand-up, if he heard anybody chatting . . .

RL: If they just ordered a drink, like, “I’ll have a Scotch and soda,” he’d walk off.

KS: I understand that.

RL: In a nightclub, though, people are allowed to order a drink and an hors d’oeuvre. But not in Larry’s world. The thing about Larry David . . . I mean, we’re polar opposites. I wear my heart on my sleeve. He has a big heart, but he doesn’t necessarily feel like sharing his feelings. That doesn’t mean he doesn’t have them-he has plenty of them. We became absolute best friends when we were around 25 or 26. We had no idea we were the same kids who hated one another when we were 12 until one time at the bar at the Improv in NewYork. I said, “God, there’s something about you that scares me, like a Roman Polanski kind of deal.” It spooked him. We somehow decided to retrace our childhoods, and I said, “I went to this camp.” He said, “What camp?” and I told him. He said, “I went there.” So I went, “Wait a minute-you’re that Larry David?” We almost came to blows.

KS: What do you say when young comedians ask you for advice?

RL: They ask for advice, and I go, “Listen. Nobody is you.” Paul Schrader, when I was about 29, was giving a lecture after he finished writing Taxi Driver [1976]. I’ll always remember this. He said, “Listen, you don’t have to be Robert Towne. Nobody lived your life.” I was mainly a comedian back then, so I took it to heart as a stand-up. He said, “Nobody knows you better than you. So write what you know.” To me, that meant, “Say what I know and talk about my feelings and my guts.” Schrader’s advice is what I pass on to everybody. Listen, if you’re talented and you do what you do that way, there’s no stopping you. I guess you’ve got to have talent-and a little luck. But if you don’t really go down deep, down to your guts, then I’m not interested.