IN CONVERSATION

Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal and Padma Lakshmi on Politics, Policy, and Purpose

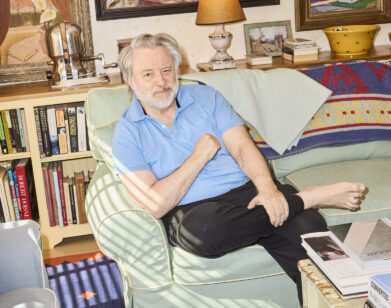

Pramila Jayapal. Photo by Jenny Wohrle.

When two powerful people get together to talk politics, there is often great potential for insight—even for change. Such is the case when the United States Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal hopped on the phone with the beloved television host, writer, and activist Padma Lakshmi. Jayapal, who represents the state of Washington’s 7th congressional district, wears many hats, but her work has focused largely on immigration reform and, of late, a $15 federal minimum wage. The progressive Congresswoman also made headlines when she spoke about her experience in the Capitol Building during the January 6th insurrection, after which she contracted COVID-19—a result of holding up in the chamber with several maskless U.S. officials.

As the longtime host of Bravo’s Top Chef, and more recently, her Hulu show Taste the Nation, Lakshmi has made a name bridging the topics of food, identity, and politics. The author of Tangy Tart Hot and Sweet, Lakshmi is even more passionate about socio-political reform and immigrants’ rights than she is about the history of the tortilla—though she could talk at length about those, too. So when she had the opportunity to speak with Jayapal at a critical moment for the future of the country, Lakshmi—whose family hails from Jayapal’s native Chennai, India—made sure to give us plenty of food for thought.—JACOB UITTI

———

PADMA LAKSHMI: Hi!

PRAMILA JAYAPAL: Hi! This is such a fantastic, wonderful thing, to be able to talk to you!

LAKSHMI: Oh, it’s so nice to meet you. I think we met very briefly a long time ago, maybe at an EMILY’s List thing? Am I wrong?

JAYAPAL: It’s possible. Though, I feel like I would remember that because I watch you in Top Chef and I watch you in a number of other things. So, maybe we did and maybe it was just in the midst of a big crowd.

LAKSHMI: Probably. First of all, congratulations for doing a kick-ass job.

JAYAPAL: Thank you, thank you. It’s been a few months, that’s for sure.

LAKSHMI: Can I ask you where in India were you born?

JAYAPAL: I was born in Chennai. Is that where you were born, as well?

LAKSHMI: I was born in Delhi, but my family is Chennalian. I live in New York but my family still lives in Chennai. My uncles, my aunts, my granny is still there. So, I am very tied to Madras. I still call it Madras.

JAYAPAL: I still call it Madras, too! [Laughs]. Well, I was born in Madras but my family is from Kerala. But my grandparents lived in Madras for a lot of their life and my grandfather retired there. My grandmother, when she passed away, they were still living in Madras. And now my parents live in Bangalore, so we’re all Southies.

LAKSHMI: Same! Are you from Palakkad in Kerala?

JAYAPAL: I am, how did you know that?

LAKSHMI: Crazy! Because we are Tambarams from Palakkad, like right there.

JAYAPAL: Well, one of the amazing things about India is probably if we talked long enough we’d find some connection. I still remember when I found out that Kamala Harris’s aunt was a student and a mentee of my great aunt.

LAKSHMI: Wow!

JAYAPAL: They were both OBGYNs and they both ended up being deans of the Chandigarh Medical School. It is remarkable.

LAKSHMI: I’m going to get really nerdy now. Where in Chennai? Because Kamala’s grandfather lived around the corner from us in Besant Nagar.

JAYAPAL: Okay, we were in Anna Nagar.

LAKSHMI: I know exactly where you were. So, you speak Tamil, or Malayalam?

JAYAPAL: Not at all. I can speak Malayalam, but very badly. I can understand it and I can hold my own in listening and getting the gist of the conversation. But to my mother’s great dismay, I do not speak Malayalam well. I speak Hindi better because I went back and lived as an adult in the north and learned to speak Hindi there.

LAKSHMI: Ah, I see. Where did you live for the first 16 years of your life?

JAYAPAL: The first five years, we were in India in Madras and Bombay and Bangalore. And then we moved to Indonesia. So, I actually grew up in Jakarta for 12 years with a break in-between for two years in Singapore, and then came to the United States for college.

LAKSHMI: I see. I’m so cheering for you and rooting for you, and I think you have done such a great job. And I don’t know if you saw, but I put up you grilling William Barr [on Twitter]. I was like, “Yes! Go!”

JAYAPAL: I saw that and it made my day! I immediately texted my staff and said, “Look, this is so wonderful!” And you, too, have been so outspoken on immigrant rights and on so many critical issues. It’s been a wonderful thing to see you using your platform in that way.

LAKSHMI: What made you want to go and run for office? I know you’ve had an illustrious career in healthcare and advocacy. Tell me about the moment when you said, “You know what? I’m going to run.”

JAYAPAL: Well, I had been leading this organization I started for immigrant rights after 9/11 and everywhere I went, as we tried to move federal policy and local policy and state policy, I felt like I had to explain too much about what the issues were for us as immigrants and as people of color. I was working on the $15 minimum wage. All of these things felt like they were just too hard to explain to people. I really began to notice that there were not very many people who looked like me. There weren’t very many immigrants, there weren’t many women or women of color.

But I always had this view that it was better to be an activist on the outside than to be an elected official. I was quite dismissive, actually, about a lot of people in elected office. And I just realized one day that I was thinking about it all wrong, that we actually, as activists and organizers, had an opportunity to think about elected office as just another platform for organizing. And that was a theory of change, if we were at the table—Shirley Chisholm, of course I read her book. I felt like, ‘Okay, we can either be at the table or be on the menu, and maybe it’s time for more of us to get in.’ So, that was it. I just made the decision in two weeks. It was like a light bulb went off for me and that was when I went for the [Washington] State Senate in 2014.

Padma Lakshmi. Photo by Inez and Vinoodh.

LAKSHMI: As a representative of the U.S. House, do you feel the pressure to have to campaign? Because a two-year time period is not a lot of time and you’re always going back and forth between your home state and D.C. to be present, to vote and do all the things you have to do. What is that like? That is the thing I’m always curious about.

JAYAPAL: Yeah, it is really hard, I’ll be honest. And part of it is the crazy system that we have where you’re supposed to fundraise, which means that people start fundraising immediately. I don’t take any corporate PAC money, so everything I get is from individuals. That’s just a philosophy I have. But to run every two years is challenging because of the political fundraising system that we have. Otherwise, there’s a beauty to having to run every two years because if you really were focusing your campaign just on connecting with people, which is what I try to do, it’s a wonderful opportunity to be able to talk to people and engage with your constituents on a regular basis. But the challenge of going back and forth is very real, particularly when you live on the West Coast and you have a five-hour flight every week that you have to take out. But that’s just part of how we legislate and how Congress works.

LAKSHMI: I have so many questions! I know that you’re on a couple very important committees, and I just wanted to ask you what happened to the $15 minimum wage legislation. Why didn’t we pass it in the Senate with the Relief Bill?

JAYAPAL: Yeah, it was really distressing. It all comes down to the crazy rules in the Senate that essentially allow senators to filibuster and stop a bill from moving forward unless you have 60 votes. That filibuster rule is something that is the legacy of white Southern segregationists who put that into place in order to prevent movement forward on Civil Rights, and that has then led to the idea of, ‘Okay, let’s find a workaround on the filibuster and we’ll do it by having certain bills that are tax bills and have an effect on the federal budget—those we’ll lower the threshold for and require only 51 votes.’ It’s the same thing with Supreme Court Justices. Republicans have changed the filibuster rule to require only 51 votes for Supreme Court Justices.

But we end up in what I’ve been calling the “Parliamentarian Pretzel,” which is just trying to twist ourselves into strange positions in order to try and get something to qualify for what is called “reconciliation,” or the 51 votes. And that meant that we had to show that minimum wage could have a significant effect on the budget. The president of the Senate [Vice President Kamala Harris] can overrule the Parliamentarian, take the advisory opinion, and say, ‘thank you very much but we’re going to go in a different direction.’ The White House just wasn’t willing to do that. So, because we passed the bill through reconciliation, the Parliamentarian ruled that $15 an hour was a policy and didn’t have enough of an effect on the federal budget, and that it couldn’t be included.

It’s a very wonky way of talking about this because, at the end of the day, nobody outside is going to care that the reason we didn’t raise the wages of 32 million people is because some unelected Parliamentarian said we couldn’t. You know, that is not a good argument to go back to people with.

LAKSHMI: Yeah, and that’s why I’m asking you—why do you think that the White House was not wiling to say, you know what, this is important? Because they campaigned on that.

JAYAPAL: I think that they just chickened. President Biden is somebody who believes in the rules of the Senate. It took him this long to say that he was even willing to consider any reform to the Senate rules, but he has not been somebody who’s generally been interested in challenging Senate rules and procedure. But the argument we have made to him—and I believe that we will be successful in the end—is these procedural arguments are not going to win us back the White House in four years and they’re not going to allow us to take the majority in two years. We have to be able to deliver. And that’s the message, I think, that is really important for everyone on the outside to be sending. At the end of the day, it is not unprecedented to overrule the parliamentarian. It was done in 1969 and in 1974 and this is certainly the best reason to do it, to lift 32 million people’s wages up and to lift 1.2 million people out of poverty.

LAKSHMI: Exactly. I mean, I just know that it’s impossible to live on. The federal minimum wage is not a living wage.

JAYAPAL: No, it’s so far from a living wage. You know, Padma, I was on the committee that designed the policy to raise the minimum wage in Seattle back in 2014. We became the first major city in the country to raise the minimum wage to $15. It was graduated, as well. But we are now at $15. And even here—and where you live in New York City and in California in most cities—$15 is no longer a living wage. So, lifting the floor is something that is so essential. Then, of course, there will be cities and states that continue to raise the minimum wage to deal with the higher cost of living in those places.

LAKSHMI: What has been the most challenging thing for you now that you are a lawmaker that you didn’t expect?

JAYAPAL: That’s a great question. I think the most challenging thing is that we have to vote every day on any number of policies. When I was an organizer on the outside, I could hold out for the perfect thing. We could say, “This I what we want and we’re not going to say yes to something that’s less than that.” And we didn’t have to weigh in on every single issue. But as a lawmaker, you actually have to vote yes or no. There isn’t a “I’m going to withhold my vote” option there. I find myself having to make this very tough decision about, is this good enough to move it forward versus is this something I can truly embrace? And I think those are two different things that, as activists, we don’t have to confront quite as much.

LAKSHMI: Yeah, you have to pull the trigger one way or another. Another thing I wanted to ask you about—and this is my opinion, not yours—but I think Betsy DeVos was one of the worst things that happened to education in this country.

JAYAPAL: Totally! I am with you, 100 percent.

LAKSHMI: I don’t know her personally, I don’t want to know her. But it seems to me that regardless of whether you are conservative or liberal, if you really believe in the progress and success—financial, environmental, healthcare, all of it—of your future population in our country, that you invest a lot of money in education. Because these are the children who are going to be running the world when we’re retired. So, you can be fiscally conservative, you can not share views on a number of issues – but why is it, do you think, that the Republican lawmakers are so against putting more money into education? Or nutrition, school lunches. You hear that a child’s lunch, you’re only able to spend $2 on it. I remember working with Sam Kass years ago, he came on Top Chef and we talked a lot about this. It’s really, really appalling to me. Also, putting money to hire trained teachers in public schools, to have arts and music and those kinds of things. Why do you think that seemingly intelligent, good-natured people don’t believe in that?

JAYAPAL: I can’t answer for the Republicans. They have become a party that I literally do not understand anymore. They don’t stand for a set of principles even, much less values. And I know that’s a big statement, but, you know, I was trapped in the Gallery on January 6th and I have to work with people who continue to refuse to admit that Biden is the legitimate president or that there was anything wrong with happened that day. So, I feel like when we’re in the education committee and I hear Republicans opposing additional money for kids to be able to get a good education, or my “college for all” bill that President Biden has embraced for free higher education for two-year and four-year colleges, and they talk about it as a handout when we all know that most countries in Europe, you pay minimal amounts for higher education because of exactly what you said… People understand this is an investment. K-12, even childcare, pre-K and higher education, this is the future. If we invest in people now and we give them the skills and the training and the education they need, then it will pay back a multitude of times. I can just speak for us, for progressives—we really believe that the role of government is to equalize opportunity for everybody.

LAKSHMI: That’s right.

JAYAPAL: I think Republicans don’t believe that. They believe that the wealthiest and the biggest corporations should just have free reign. Even on minimum wage, this was the argument that they were making: why should we set a minimum wage at all? Why should we have a federal minimum wage? We should just let people do what they want to do in states or even let businesses do what they need to do. That is their approach and I think it’s just completely wrong.

LAKSHMI: It is completely wrong. Do you think these are the same people who would have been against any kind of free education or public education? Even elementary or high school? I don’t know what to make of saying it’s a handout.

JAYAPAL: Yeah, I think that is where increasingly they have been going. That was the discussion we had on minimum wage: do you believe in any minimum wage? And some of them were quite proud to say no. And I think on schools, they have been successful in undermining our investment not just in public education, but really in education across the board. The government used to pay for a substantial amount of even higher education, between states and federal government.

LAKSHMI: Junior colleges.

JAYAPAL: Exactly. Now it’s maybe 30-40 percent of community colleges or public universities that’s actually paid for, and that doesn’t include all the additional expenses of housing and books and everything else. So, for the Republicans, I think they’re honestly quite willing to have a big portion of the population not be educated because they may even see it as beneficial. I think that’s really the fight that’s in front of us and that’s the argument that Democrats have to make over and over again—that government is the great equalizer of opportunity. We believe in investing and it pays back so many times when we do.

LAKSHMI: Congresswoman, you’re certainly a force to be reckoned with in the House. But do you see yourself maybe transitioning to another role in government down the line or some other elected office?

JAYAPAL: You know, maybe? I think I’ve always been somebody who’s particularly bad at planning for the future and thinking about what I want to do next. [Laughs] Leading the progressive caucus has been a real privilege and an incredible opportunity for me because we have 96 members now. We’re about 44 percent of the Democratic caucus and we’ve been able to really leverage our power and to push bold, progressive policies and to win on many of them. I’ll just keep my eyes open and see what emerges next.

LAKSHMI: Sounds good. People always ask me that question or say, how did you plan your career? And I always say, “You’re assuming I planned my career!”

JAYAPAL: Well, I have that question, actually. How did you decide to do Top Chef? I mean, you’ve had so many different pieces of your career. But did you plan all of that?

LAKSHMI: I really did not. I studied theater and American literature, and I was auditioning as an actor. I paid off my college loans through modeling after college. But I was just a young actor. And while I was modeling to make ends meet—it’s like being an Olympic athlete, you can only do it for so long, really—I was also auditioning as an actor and writing. So, I wrote a cookbook, just as a fluke. And that’s how I got into food. I always loved to cook but I never went to culinary school and I certainly didn’t work the line in a restaurant kitchen. I only got that cookbook deal because everyone wanted to know what a model ate. I don’t think anybody thought that much would happen with that cookbook. But it won a prize in Versailles and then I was invited as part of my book tour to come on The Food Network. It was there that they asked me back right after I went on. Then my manager, who really was just my acting manager, said, “You’re going to have to pay her if you ask her back a third time.” And they offered me a development deal.

That is how I started my first cooking show on The Food Network, called Padma’s Passport. And when Top Chef came along, I had pitched Bravo! another show that I wanted to do that they thought was a little too niche or high-brow, but they were developing Top Chef and they asked me if I wanted to come on and develop that. I’ve been with the show since the second season. From there, it took me over a decade to get Taste The Nation made. You would think it would be easy with Top Chef—and I’ve been nominated for 32 Emmys—but it’s very hard to get a show made or do anything in Hollywood if you are a brown female or an African-American.

JAYAPAL: Which is why it’s so important to have you there. I am always looking for the Desi women who are out there doing amazing things because I think we are so often the only ones in the room that look like us. We have so many more challenges and it’s so meaningful for people to see you there. So, I’ve watched Top Chef with my 24-year-old growing up quite a bit and it was just so much fun. It was fabulous to see you there.

LAKSHMI: Thank you. I always notice the Desi women because there are so few of us, especially in the media. Now, of course, Priyanka Chopra has made the crossover from Bollywood and we have women like Mindy Kaling. But fifteen years ago when I started, other than Sanjay Gupta, I think I was the only Indian person on TV! That’s why I did Taste the Nation—even on the campaign trail with Trump, there was such negative, terrible rhetoric about immigrants. And as an immigrant and as someone who grew up in an immigrant community, that just wasn’t my experience. I thought that they should have a platform to speak for themselves, and that is how Taste the Nation was born. It was born out of the work I had been doing for four years with the ACLU on immigrant rights. I thought, “These communities can speak for themselves. They are just as American as anyone else.” Really, Taste the Nation is a political show disguised as a food show because it uses language people are used to hearing me speak all the time. It’s also a great key into getting people to open up. They may not want to talk religion or politics, but everybody wants to talk to you about their grandma’s cookie recipe.

JAYAPAL: That’s really brilliant. You probably know that I was the first member of Congress to go to a detention center, a federal prison actually, where parents were being held after being separated from their kids.

LAKSHMI: Yeah, I remember.

JAYAPAL: And now we’re seeing again at the border all the challenges that are coming up around what the Trump administration has done in destroying the infrastructure that exists, but also how broken our system has been for a long time and, frankly, it’s been both parties that have not been able to make the changes that we need to make.

LAKSHMI: That’s right, and it’s important that you say it that way. A lot of these policies were happening before Trump, and I think in having the moral high ground it’s important to acknowledge that.

JAYAPAL: Oh, absolutely. I miss President Obama, I liked President Obama very much. But I was also one of the activists who called him the Deporter-in-Chief because we were deporting more people under President Obama than we had under any president prior. You go back to 1996 and Bill Clinton, and the criminalization of immigrants really began with the immigration laws of that time. So, there’s a lot I think that’s important to recognize. Trump certainly took everything to a whole different level, no question. But we gave him the tools to do that. Before we go, would you like to talk about Georgia?

LAKSHMI: I would like to talk about that incident that happened a few days ago in Georgia because it is intersectional. And I want to talk about it from that angle because, of course, there’s xenophobia. But it’s also gender-based violence and it is also a gun control issue. And I think that the law enforcement officers who were trying to frame it not as xenophobia but as a sex addiction-motivated crime doesn’t change that it’s a hate crime. And the fact that the law enforcement officer is saying “he had a bad day”—I couldn’t believe I was hearing it, myself. It made me sick. It just shows you how deep-rooted and interconnected these issues in our society are. It’s xenophobia, it’s gender-based, it’s misogyny, but it’s also a gun control issue. He could have felt whatever he felt, whether it was about Asians or women or both, but he wouldn’t have been able to do anything about it if we had better gun control laws.

JAYAPAL: Yeah, it’s really important because I was frustrated with the simplistic ways in which it was being described, and I think as Asian-American women, we understand all of the different complexities of this. You can go back to the exclusion of Asians in our immigration laws and in our culture in this country, from the Chinese exclusion to the Japanese internment to not being able to naturalize. There are so many different pieces that are built into the structure of our laws. But also, the remarkable and really outrageous comments that were echoed then by Christopher Wray, the FBI Director, that this was sex addiction and not racially motivated, were stunning to me. Because how did they so quickly determine that was the case? The idea that somehow just because it’s a sex addiction that it wouldn’t also be racially motivated completely ignores the hyper-sexualization of Asian women, and so many other pieces that were prevalent in this situation. We were pushing for the hearing in the judiciary committee, which then happened on Wednesday or Thursday. I was a part of that hearing and it was outrageous to hear Chip Roy, a Republican, make the comment about how “in Texas we get a long rope and get the tallest oak tree.” A deliberate connection to lynching. But of course it is all connected, because white supremacy runs through all of this. At the end of the day, Asian-Americans across the country are hurting because we have been invisible-ized for a long time. When you look at even politics and polling, how often do we see a poll that has other groups of people of color but no data on Asian-Americans, because we’re “statistically insignificant?”

LAKSHMI: Right.

JAYAPAL: How often is it that we have the “model minority” myth put out there, but no desegregated data on health or income or any other piece that allows us to target real policy solutions towards Asian-American communities? Even if you look at representation, this is actually the first administration in a long time that has not had an Asian-American cabinet secretary. Even in the Trump Administration there was an Asian-American Cabinet Secretary, Elaine Chao, as has been the case for some number of years now. It’s a complex time, and a scary time for people across the country who are wondering if they’re safe just walking home at night. But even as we talk about all that, the growing power of Asian-Americans across the country, including in Georgia, has been wonderful to see. Padma, thank you for everything that you are already doing. It’s a delight.

LAKSHMI: Thank you, thank you. It was a pleasure to speak with you.