literature

Novelist Andrew O’Hagan’s New-Wave Ode to Youth and Friendship

“Being young is a kind of warfare in which the great enemy is experience.” This line appears in the first paragraph of Andrew O’Hagan’s latest novel, Mayflies, and it grips you roughly by the throat. It’s the kind of beautiful and audacious sentence that has cemented the reputation of the 52-year-old Scottish writer, who moves seamlessly among journalism and fiction, hard-hitting beat reporting, cultural essays, and literary prose (sometimes, as with his debut masterpiece, 1995’s The Missing, within a single text). But even for an author who has walked so many lines and conquered so many subjects, far away and close to home, Mayflies proves a particularly personal project.

The novel centers on the friendship between the narrator, Jimmy Collins, and his best friend and idol, Tully Dawson, neither of whom can be contained by their small Scottish mining town in the summer of 1986. Heading to a music festival in Manchester where The Smiths are headlining, the characters embark on the kind of feral, debauched, wildly hilarious picaresque from which youthful memories are made. O’Hagan is so good at capturing the play and hijinks of these quick-witted, oft-wasted young men (in the midst of a next-morning hangover, Jimmy remarks, “my mouth felt like the Second World War”). But the devastations of adulthood can only be kept at bay for so long. The second part of Mayflies finds Jimmy, a successful writer, in the summer of 2017, where he learns of Tully’s terminal illness and his request die on his own terms—with Jimmy’s help. As it turns out, the novel follows O’Hagan’s own relationship with his childhood friend, Keith Martin, who also died of cancer in 2018, and was created out of a promise to tell their story.

I met O’Hagan a few years back at a writers’ festival in Mantua, Italy. He had just gotten married, and, bride in tow, was on his way to his honeymoon in the south. At that wedding, his friend Keith served as best man. I spoke with the London-based writer last week via Zoom, and there he was, fireside, in a lovely green sitting room somewhere on the planet.

Old friends: Andrew O’Hagan and Keith Martin in 2018, the year Keith died.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: You’re sitting in front of a fire in May. Where are you?

ANDREW O’HAGAN: I’m in my apartment in Edinburgh. It’s the most beautiful city in Europe, you know.

BOLLEN: I didn’t know that. I’ve never been.

O’HAGAN: Well, the country just opened its doors after the hurly burly of the pandemic so I thought, “Fuck it, I’m going to go up there for a few days.” I’m in the middle of a big book, so I thought I’d do some writing up here.

BOLLEN: We’re here to talk about Mayflies, but what’s this big book you’re writing?

O’HAGAN Well, I’ve been working for six years on a huge epic social novel set in London during present times. I really conceived of it in the years just after the banking crisis and started to do some old-fashioned Dickensian pavement-pounding and research. For example, I started going to the polo with the Royal Family. I started tying it with Russian oligarchs. I started paying attention to the whole way that London works. For a long time I’ve wanted to write what Henry James rather funnily calls in one of his short stories, “A huge grotesque epic of London’s society.”

BOLLEN: The new Gilded Age of the London rich.

O’HAGAN It’s a Victorian novel set now, as it were. I’ve been eating my Trollope and my Thackery and my Dickens and I’m ready to rock.

BOLLEN: Tell me it has some Wilkie Collins twist and turns in it too?

O’HAGAN: Even more than my life, if that can be imagined. Yeah, it’s full of surprises and duplicity and also a sense of social consequences. The differences between rich and poor, between haves and have nots, are really at the core of this book. I’ve never written a book like this before, actually. All my books have been quite chamberpiecey and small.

BOLLEN: I have a mental-health-writer question. I often find when I’m writing a book that I develop a panic about it needing to come out as soon as humanly possible. Do you feel that urgency or do you give yourself all the time in the world?

O’HAGAN Somewhere bang in between. I do get that feeling from time to time, thinking, “Christ, this must come out now,” because in a sense, it’s going to chime with the way that people are living right now. But usually, I’m spared that and I can just sort of spread my elbows a little bit and take the time. And I don’t publish a book every year. It’s always every few years. And even at the point of delivery, you’re still a year away that you’re from publication.

BOLLEN: Yes, book publishing is like slow food. I think it’s because I started out in magazines, which is much faster than books. But you also come out of a non-book journalist background.

O’HAGAN: I grew up on longform journalism. That’s where I made my name, and I started quite young, in my early 20s. To tell you the truth, I grew up on the great classic American perpetrators of that crime. Norman Mailer and Joan Didion and Lilian Ross, and Truman Capote and Tom Wolfe meant so much to me when I was young, and I was constantly learning from them. It’s funny talking for Interview. Where I grew up in Scotland was so remote and so away from the Western world in some sense, but there was a shop on our main street of this little village where the guy was quite enlightened and stylish and he always had a copy of Interview magazine on the shelves, usually like two months late. I’ll never forget their famous illustrated covers and just how beautiful everybody was in the magazine. I remember being young and transfixed by the sheer exotic nature of this magazine. And that sort of dovetailed for me with an interest in American writing and American reportage, the whole American conversation, really. It gave me a start.

BOLLEN: Capote was a contributor to the magazine for a few years. But you bring up Mailer. It’s fascinating to me how much his reputation has taken, not a dip, but a hard plunge into obscurity, since his death—and for all the obvious misogynist reasons. I’m curious, do you think Mailer will ever be redeemed?

O’HAGAN: Having just witnessed the whole Blake Bailey fiasco [Philip Roth’s biographer] and looking at how the great triumvirate of American male novelists of my teenage years, Bellow, Roth, and Mailer—and Updike, if you want to throw him in—those four men are sort of being scraped off the syllabus as we speak

BOLLEN: Completely. The chisel is out on of their names.

O’HAGAN: I think Norman saw it coming. I went to Provincetown a couple times to interview him and spend time with him. I did three days there for the Paris Review with him and he saw it coming. He said that there was a kind of fundamentalism entering into American life, as he described it. Obviously I am far more sympathetic to the accusers than he would be because it’s much more my generation than his by a distance, but it’s still rather more alarming than I expected it to be because I do still believe that moral crimes don’t instantly cancel out literary genius. And that’ll be a debate that never ends. If we go through the canon assassinating all offenders, then we’ll have nothing left. A few short stories, maybe.

BOLLEN: I agree. To me, it comes down to a radically different definition of the sainthood expected in our artists. Once it was outlaw bohemianism, but that ruler doesn’t measure up anymore. Now it’s a very different ethical test.

O’HAGAN: One of the things we must remember without being patronizing is that cultural movements have every right to have their moment and have a head of steam. And it’s long overdue in some respects, especially with Black Lives Matter. We’ve been living with a kind of obscenity of a lack of published Black authors in our industry, the lack of Black editors on literary papers, the lack of Black models on covers. I’m delighted it’s coming to an end because of course, the sense of a more interesting and more moral world is exciting. But as for going around with a certain net catching all the vagrant geniuses who have committed crimes, I just don’t have time for that in the end. I’m much more interested in inclusivity in the present rather than excluding people from the past.

BOLLEN: Speaking of vagrant geniuses, did you watch Ken Burns’s Hemingway documentary on PBS? I thought of you because your pal Edna O’Brien appears on it.

O’HAGAN: Oh yeah, Edna was really in her Ednaness, didn’t you think?

BOLLEN: She was mesmerizing, and so wise. She sort of stole the documentary, I thought.

O’HAGAN: I said to Edna, “I don’t know where the world would be without your hairdresser.” Edna arrived on screen with such a clear and distinctive presence, and she didn’t say the usual stuff about Hemingway. She had a way of understanding his value, I think. And it was very much the everyday common language of Edna. You would think that she had worked herself up into this great spiritual high mindedness in order to speak. No, that’s the way she speaks when she’s asking you to pass the wine.

BOLLEN: I need to have dinner with this woman! Okay, now we’ve got to get to this amazing novel of yours. You said you were writing away, six years into your London social grotesque. What pulled you away to write this gorgeous tribute to youth and friendship?

O’HAGAN: Because of my dear friend from childhood, Keith Martin, who was my best man when I got married and my great buddy going way back. He was the guy, the lead singer in the band, the most handsome guy who anyone knew. All the guys either fancied him or wanted him to be their best friend, the girls all loved him, the highest cheekbones in Europe, the best record collection in Scotland. He was that guy. And he never really moved away from the small town that we grew up in. He moved like 20 miles away and that was thought to be a great journey for him.

BOLLEN: Was he also a teacher like Tully is in your book?

O’HAGAN: He became a teacher, yeah. And when he was dying, before my wedding, he said to me, “Would you ever write about us?” Because all that growing up and that hurly burly of teenage years and politics, we were so anti-Thatcher and supporting the miners during The Great Miners’ Strike of 1984-85. I was nipping off to read Interview magazine coming from a strike meeting. That’s the kind of life that we had then and we loved the glamor of music and film, and he was my buddy when it came to all that. When he was dying—he had esophageal cancer and he knew he only had months to live—he asked me to do it, and I thought, “I’m going to do this.” I just didn’t realize I was going to do it immediately while the whole thing was so raw. But I did. I put down the other book and just started writing this one.

BOLLEN: You capture the rich, recklessness of youth so well in the early chapters of the book. Were those teenage years of abandon easy for you to access, or did it all really feel like visiting a foreign country?

O’HAGAN: The past did feel like another country, but it was one that I knew how to navigate. I found myself back in its byways and its main streets with all the music of that time. It all came back to me so vividly and so quickly that it was almost as if it were a record that had continued to play in the back of my mind all these decades. We had one of those childhoods which was ripe for a long time, probably because it was a war with our fathers. Our fathers were so working class and hetero-sexist and hated the music and movies that we liked. Their style was stuck somewhere in the 1940s. And that’s good material for a novel. Even before Keith was ill, the past was ripe and sort of present to us because our fathers were all similar. I knew I’d wonder back there some day and try to capture the distance between us, the distance between that particular generation, because the world that we’re now embracing with all its changes and its absolute timely liberations in terms of gender, sexuality, queerness, and Black lives, all of that was not only foreign to our parents, but they were kind of in opposition to it. So even speaking as a man of 52, I was of that generation where those things were beginning to open up, thank god, and my chief cheerleader in that department was my friend, Keith. So I knew that I’d make a novel of it someday.

BOLLEN: There are great scenes where the characters quote movie dialog back to each other. That could seem like an inauthentic mode of communication, but when you’re young those jewels that you pluck from pop culture feel so meaningful, like a secret code among friends—especially when you live so far from the cultural center. You capture that youthful need for movies and film so well.

O’HAGAN: We were in this small town 25 miles outside Glasgow in the west coast of Scotland. We hardly had a discotheque. And yet, we all wore stripey T-shirts. We all knew who Edie Sedgwick was. We’re all obsessed with films. This is a tiny town. We all wore wraparound shades and loved The Velvet Underground. Your childhood, whilst it might seem so remote from mine, is actually quite similar when it comes to fandom, I would imagine. Those freedoms that we sought were kind of international and they weren’t to do with the folk tunes of the local tribe. We loved that all that fabulousness was available to us too. When I finally got to New York, I felt like I was visiting not this foreign place, but this extension of my childhood. We watched all the moves and read all the books. I knew what a brownstone was although I’d never seen one. An, yes, friendship became mutual fandom. That’s actually one of the things I love about fashion—it is a kind of international fandom. Whether you can buy the jacket or not, you can think about it and it’s familiar to all of us.

BOLLEN: Did you and your friends actually venture to Manchester for a music festival like they do in the book?

O’HAGAN: On the19th of July, 1986, there we all were when those descended upon that venue. We went there on the bus just as I describe in the novel. This is the most autobiographical piece of work I’ve ever written, without a doubt. I took the licenses that I had to take, but I didn’t have to take much. I had to take some freedoms so as to protect certain individuals and to heighten the drama and to bring it together, but in fact, all these central locations and central characters are from life. I was surprised in a way by how available to fiction it was. It sat there like a finished story in my head and all I had to do was transcribe it.

BOLLEN: I loved the moment that The Smiths make a cameo, the band members walking out to their car.

O’HAGAN: That happened.

BOLLEN: It reminded me, on a much less impressive scale perhaps, when I went to the movies in third grade in Cincinnati. And while I was waiting with my ticket, the members of Duran Duran walked out of one of the theaters. They were playing in Cincinnati that night and had rented out the cinema for a film. But it was like gods has suddenly, and perversely, appeared in the flesh, like they were supposed to exist on MTV not in a movie theater in Cincinnati watching Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure. My nine-year-old mind was blown.

O’HAGAN: I can tell you that’s a carbon copy of the feeling we had. It was like The Beatles arriving in your kitchen. And something that has to be said is that we were exactly like them. It was like looking in the mirror. We were dressed like them. We’d styled our jeans like them. We had hair in a crest like them. We were more or less the same age as them. And there we were standing and looking at each other as if looking in the mirror saying, “Wow, this arrival of fabulousness into the actual world.” We couldn’t get over it. And of course, the only way we could cope with it was to start shouting abuse at them.

BOLLEN: The second half of the novel jumps 30 years, when the main character is confronted with his friend’s terminal illness. Tully convinces Jimmy to help him die on his own, with dignity. I wonder, as a novelist, did you feel hemmed in to stick to the facts of your friend’s diagnosis and end, or did you still feel the writer’s freedom to heighten or change the events?

O’HAGAN: I still felt the freedom there. Keith and I had discussed and collaborated so closely on the manner of his death that it became almost like a creative project between us. Even before I started the novel, we’d had this joint enterprise to try and let him die with the same style with which he’d lived. To take away the indignity and the unknowability of it all and let him preside over it. He was such a presiding figure. And it seemed to us that if he could die with dignity and in his own time, then it would just be a glorious—although very untimely—end to this life of looking for freedom. Everything was available to the fiction. I didn’t feel I had to do any gear change and any swift turning away from events. It was all available and close.

BOLLEN: It was tremendously powerful to read those last pages where Tully is moving through his last days—his last time at home, his last morning, his last walk with his wife. Everyone has a last time, but he was aware of it, living it as the last time.

O’HAGAN: It was devastating to witness. I’m sure you have friends like this where it’s quite hard to imagine the world without them. It’s quite hard to imagine what it would be not having them to talk to. He filled in a lot of gaps for me. We could finish each other’s sentences. And to see him walk through the world for the last time was dreadful to me and it’s an experience I will never forget. I think one of the reasons that Mayflies has connected with people the way it has is, perhaps, due to the pandemic and being distant from your loved ones and being cut off from good times and common memory. I think it was also a drama that we all have to face eventually of witnessing people be in the world for the last time and indeed being in the world for the last time ourselves. And it goes to the core of life, and I was unprepared for the shock of having to face the knowledge that this guy just wouldn’t be around to share the joke anymore. I wanted the novel to carry that in slow motion for the reader, so that the reader would somehow be able to experience that themselves.

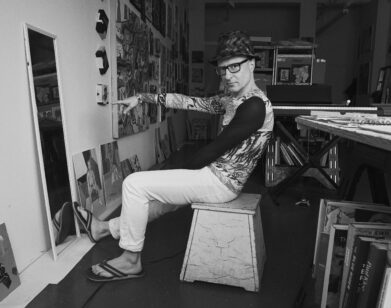

Author Andrew O’Hagan, London, 2020. Photograph by Jon Tonks.

Keith Martin aged 18, fronting the band Dead Souls in Ayrshire, Scotland, in 1985.

Keith Martin, aged 16, the inspiration for Tully Dawson in the novel Mayflies.