New frontiers: the resurgence of the West in American culture

STILL FROM WESTWORLD, COURTESY OF HBO

Few things exert more gravity within the solar system of American mythology than the Old West. For nearly two centuries it’s tugged at our psyches, a mythical theater for violence, freedom, and solitude. Images of cowboys, mesas, and lassos are indelibly linked with American cultural production. And with good reason: Who hasn’t felt the primal attraction of the myth and the look? I mean, I’m wearing cow-print pants as I type this.

The West is fluid, standing in for many things over the years; as far back as the late 1800s, traveling circuses like Buffalo Bill’s Wild West thrilled audiences with a depiction of danger and destiny lurking on the country’s fringes. A century later, in the 1950s and ’60s, television Westerns allowed Americans who felt uncomfortable with the changing world to nostalgically revisit a time when traditional gender roles reigned, and—as a counterpoint to Vietnam—adventurous violence could still feel righteous. Eventually counter-culture figures like The Grateful Dead adopted Western imagery for their own purposes; by the end of the ’70s, the country had simply overdosed on fringe. Western aesthetics spent the next few decades retreating into antique stores, Bonanza reruns, and B-movies like the schlocky Will Smith vehicle Wild Wild West.

Until now. Over the last few years, the cowboys have come home, with a recent explosion of art, fashion, music, film, and television offering updated twists on the Old West. These are not nostalgic recreations—hoary Western stereotypes are being reformatted and deconstructed to fit contemporary ideas and anxieties. Some examples, like Westworld, are literally science fiction. Stripped of cliches, the West offers a trippy new frontier for art that investigates core questions of American identity.

This year’s best TV show was a Western. Twin Peaks: The Return largely abandoned the Northwestern milieu of its first two seasons for a dive into strange events taking place on the high desert and prairie. Cars exploded on eerie subdivisions outside Las Vegas; bodies disappeared into the South Dakota sky. David Lynch reconfigured swaths of the country which rarely appear in fantasy narratives into zones of magic and death. As Dougie Jones (the reincarnation of Agent Dale Cooper), Kyle Machlachlan played the lone ranger, but he was no John Wayne—he wasn’t really anybody. Without his memory, Jones wanders around the office parks and casinos of Las Vegas, an ambient cowboy-cop without a cause.

STILL FROM TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN, COURTESY OF SHOWTIME

Only when he comes face to face with a statue of an Old West gunslinger with a pistol drawn does his memory slowly begin to return. He’s drawn to a symbol that’s long ceased meaning anything to the office-dwellers around him. Eventually he regains his identity and battles the sinister forces enveloping the landscape. The tension between ancient gunslinger cliches and real, contemporary evil is central to the show’s power. The statue—a decorative bauble in the crown of debauched Las Vegas capitalism—doses Jones with radical energy ripped straight from the dreams of mythical cowboys, unleashing him to fight villains amid skyscrapers and casinos. Lynch scrapes off encrusted layers of kitsch to reveal a radical frontier heart, a new folklore for our time.

This dynamic also exists in Westworld, the HBO sci-fi epic about a virtual recreation of the Old West in which tourists from a future America act out violent and sexual fantasies on servile androids. Westworld itself, like the Twin Peaks statue, is an image of Old West constructed to be no more than static decoration. But once again, the closed loop of lucrative fantasy jumps the tracks—the androids revolt. They’ve been artificially inseminated with attributes associated with old Western archetypes: the veteran prostitute, the gentle farm-hand, and the devil-may-care gunslinger. The spirit of the myth they serve awakens inside of them, and they throw off the yoke of spectacle.

In the modern imagination, the Western milieu is a battleground of terror and freedom. The dominant class uses it to reinforce grotesque masculinity and American exceptionalism. At the same time, downtrodden subjects draw on its old myths as inspiration to rise up against the strangulating force of globalized capital hidden within our corrupted playgrounds.

Fashion designers have also sent a slew of Western-themed collections strutting down runways over the past few years. This includes both major designers and new faces—notable recent collections from Dior and Coach incorporated fringed leather jackets, pearl-snap cowboy shirts, prairie dresses, and so on. Elsewhere, upstart fashion brand Lorod, designed by Lauren Rodriguez and Michael Freels, drew from Southwestern imagery with jacquard knitwear and rockabilly silhouettes for its Pre-Fall 2018 collection. Lorod’s press release quoted a text called Landscape in Sight: Looking at America by J.B. Jackson as an inspiration. “The existential landscape, without absolutes, without prototypes, devoted to change and mobility and the free confrontation of men, is already taking form around us,” Jackson wrote. “Our American past has an invaluable lesson to teach us: a coherent, workable landscape evolves where there is a coherent definition not of man but of man’s relation of the world to his fellow men.”

LOROD PRE-FALL ’18 BY OLIVER FERNANDEZ

Contemporary artists, designers, and filmmakers have tapped into a psychological undercurrent of live-wire tension between modern America—an often devastating, confusing place, where heroic masculinity feels bankrupt and misguided manifest destiny abroad has triggered global horrors—and the country’s older, more innocent self-conception of itself as a nation of proud cowboys.

In music, as well, a Western swerve has occurred. On the pop front, Lady Gaga’s Joanne is the most obvious example. Miley Cyrus returned to her country/Western roots this year; Young Thug let loose a raucous “Yeehaw!” on his rodeo-rap hoedown “Family Don’t Matter.” (Sandy) Alex G, one of the biggest indie rock success stories of the past few years, added a touch of bluegrass twang to his critically adored 2017 record Rocket. Electronic producers have traditionally been more interested in cyberpunk narratives and futuristic laser shows than saloons and mesa views. But last year, rising techno star Avalon Emerson opened a new door with her breakout EP Whities 006, an homage to her native Arizona. Track titles like “The Frontier” and “2000 Species of Cacti” made explicit the connection between her arid, exotic music and the desert landscapes of her youth.

“I was born in San Francisco but spent up until I was 19 living in a small town on the far edge of Phoenix, Arizona,” Emerson explained over email. “I love the push and pull between the beautiful and alien landscapes and sunsets clashing with heat, flora and fauna that will kill you if it gets the chance. My music works deeply with contrasts, so it was natural to just draw up these parallels more concretely.”

The West provides fertile ground for psychedelic visions to bloom. “The suburban human sprawl into the desert feels particularly apocalyptic and new,” explains Emerson, when I ask what the Southwest represents to her. “Most of my hometown was built about 40 years ago. The part of the frontier mythology that resonates with me, is that humans will always try to conquer and multiply even at the edge of life.”

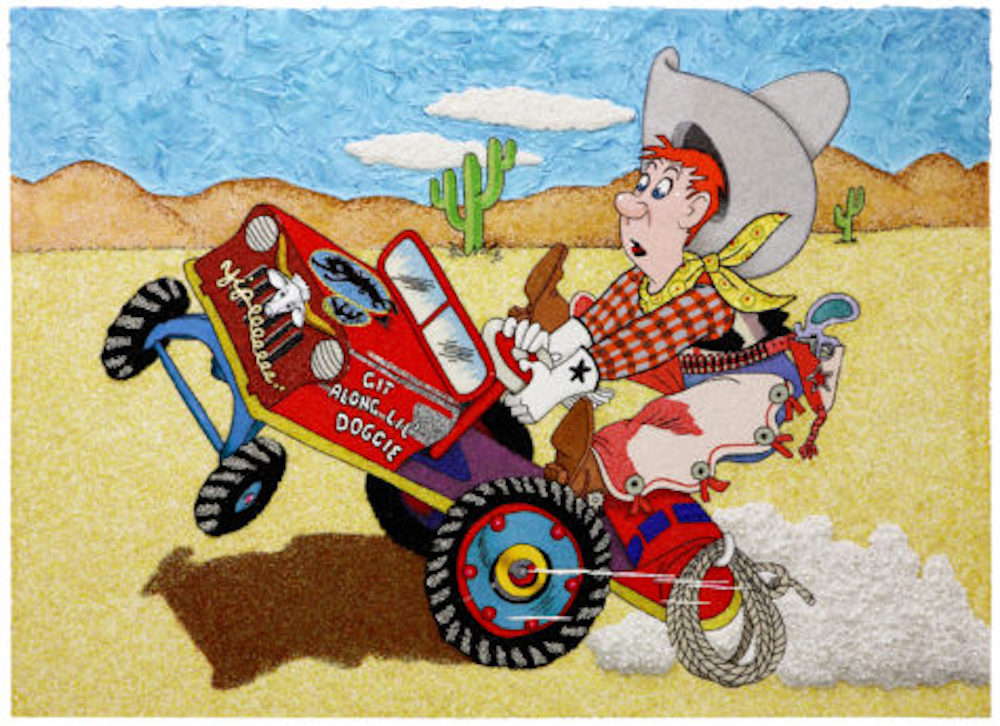

Farhad Moshiri, who’s current exhibition at the Andy Warhol Museum is titled Go West, uses pop art and kitsch themes inspired by cartoons, films, children’s books, and ads. “My father owned a chain of cinemas, so as a kid I was exposed to Western cinema,” he explained to me over the phone, describing his childhood in Iran. “Mainly Laurel and Hardy, Marx Brothers, Charlie Chaplin … as I got older it was Western movies. America is not difficult to miss, they do a great job of advertising their culture. No matter where you live you’re exposed to it.”

FARHAD MOSHIRI – YIPPEEE, 2009, COURTESY OF THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM

Moshiri’s exaggerated, bizarro versions of Western themes critique America’s cowboy foreign policy, reflecting “how Middle Easterners think of America.” But they also capture an appealing quality of the culture that he calls “romantic.” Western imagery, he told me, is “how Americans want to be seen, how they advertise themselves.” As for why these themes keep surfacing, he believes that “the world isn’t finished with this imagery. We get to look at the past again, in a new light that wasn’t shining on it before.” Western archetypes contain truths that still resonate, illustrating “a caricature version of America that speaks of the past and the present at the same time.” Somewhere or another, we’re all at home on the range.

FARHAD MOSHIRI’S SOLO EXHIBITION SNOW FOREST IS CURRENTLY ON DISPLAY AT GALERIE PERROTIN IN NEW YORK CITY. HE WILL BE THE SUBJECT OF A TALK HOSTED BY THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM ON DECEMBER 10TH IN MIAMI—CLICK HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION.