Meet the ‘private librarian’ behind the bookshelves of 1970’s Upper East Side

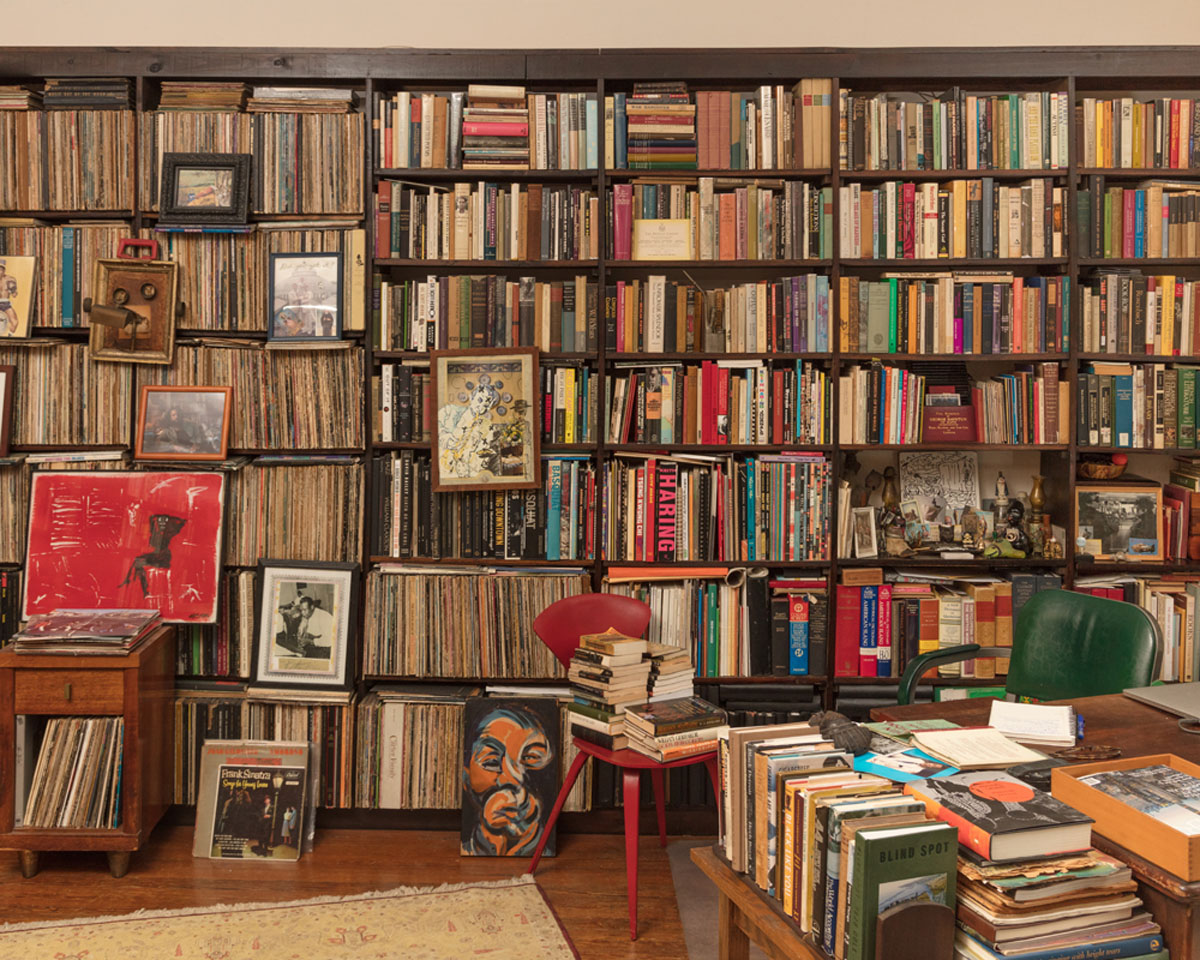

One of the many bookshelves in the Washington Heights townhouse of Kurt Thometz.

When Kurt Thometz moved to New York in 1972, one of the first novels he read was Gore Vidal’s Burr. Nearly a half-century later, the editor and book collector lives near the exact location of that story’s opening scene, in a townhouse across the street from the colonial mansion of Aaron Burr’s wife, Eliza Jumel, in Washington Heights. Instances of codex time-warping have been plentiful in the life of Thometz, whose collection has become a resource to frequent guests, such as the artists Henry Taylor and Arthur Jafa and the Man Booker Prize–winning writer Marlon James. Thometz began his career as a clerk at the legendary Madison Avenue Bookshop. He was later recruited by Diana Vreeland in the making of her exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and subsequently introduced as a “private librarian” to the area’s wealthy clientele. “Rich people actually read books back then,” says Thometz. “The only person I never saw in the store was Richard Nixon, who lived two blocks away, but I guess he was on the down-low.” Here, Thometz takes us through a life in books.

———

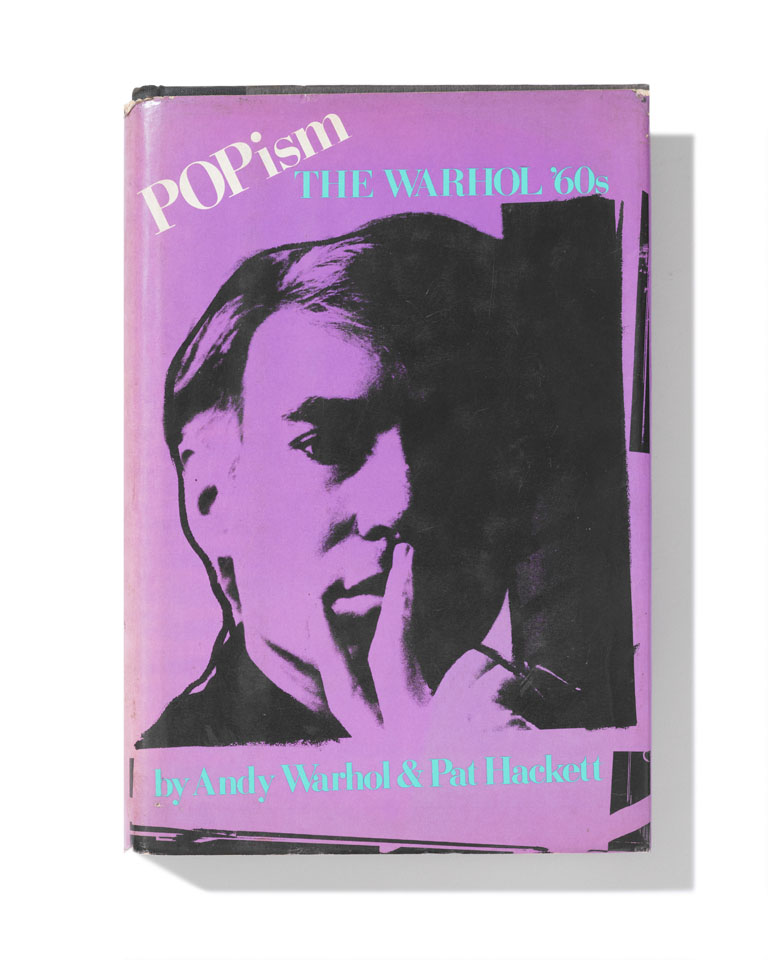

Popism: The Warhol ’60s, Andy Warhol

“I started working at the Madison Avenue Bookshop on Madison between 69th and 70th Streets in 1975, at a time when there must have been more money in that zip code than the rest of the country put together. I was a real country boy, and when I started to meet rich people, it was a very F. Scott Fitzgerald kind of thing. My boss was a man named Arthur Lehman Loeb, whose parents were the queen and king of what they called ‘our crowd.’ Arthur was one of the early supporters of Andy Warhol’s career and had introduced Andy to Edie Sedgwick, Dorothy Dean, and all those people from Cambridge. Andy would come by every weekend, and when a new issue of Interview came out, he’d drop us off a stack of magazines. I don’t remember him buying books to read, but he would always give me copies of his own, like this one.”

———

———

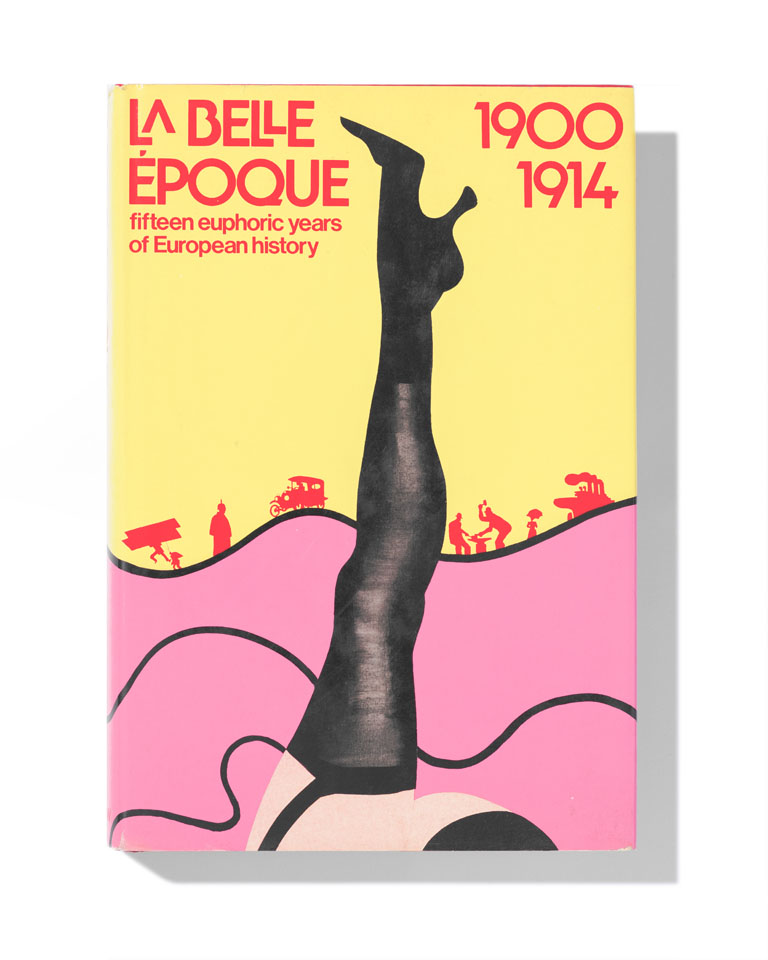

La Belle Époque: Fifteen Euphoric Years of European History, Eleonora Bairati

“Diana Vreeland was serious about books, and she used her library a lot. But she had all these twits from Vogue helping her, and they never put the books back! So her library was a mess, like a shuffled deck of cards. Then her grandson, Nicky Vreeland, who is now a monk, had a buddy come in and put the library in order. This guy smoked some pot and put the library in a Zen order, but Mrs. Vreeland still couldn’t find anything. So Christopher Hemphill [co-author of Vreeland’s Allure and D.V.], who I met at the store, asked me to step in. Mrs. Vreeland liked what I did with the library. She asked me to dinner, and I ended up coming back two times a week for the next decade. When she was working on her La Belle Époque show for the Met, I read her Proust and found books for her like this. She’s the one who invented this job of the ‘private librarian’ and started talking me up. I became Mrs. Brooke Astor’s librarian, Mike Nichols, the Mortimer bunch. When you go through someone’s books, you get to see the best side of them. The educated side. The human side.”

———

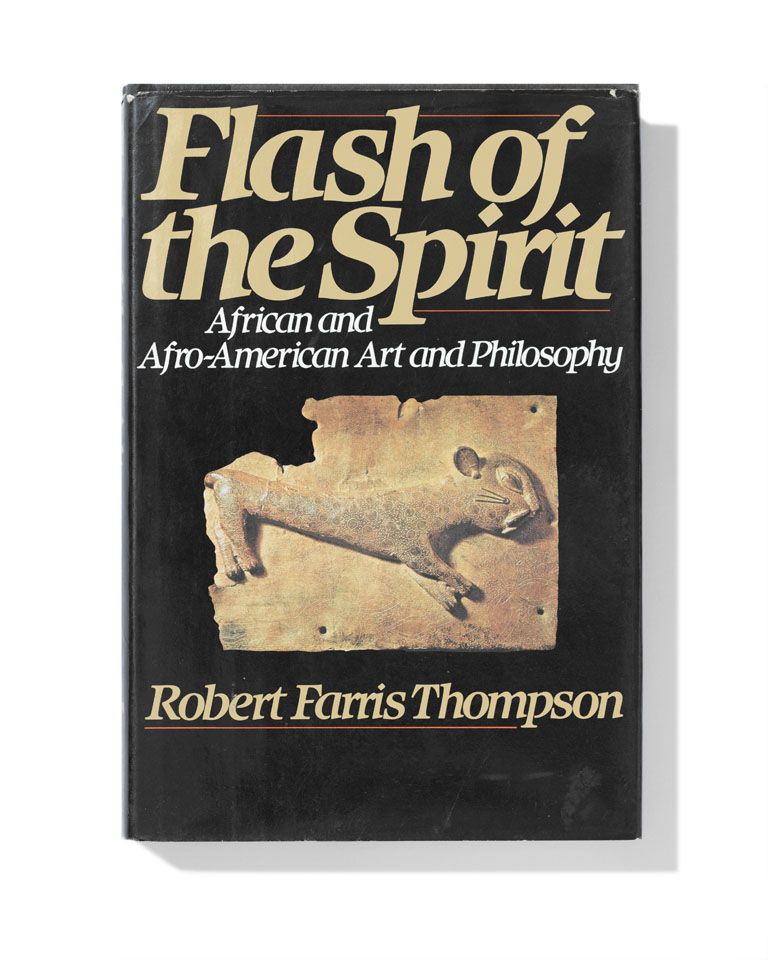

Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-Amercan Art and Philosophy, Robert Farris Thompson

“I’m an autodidact who never went to college, so, for me, reading and collecting has always been a way of collecting myself. Instead of acquiring degrees, I would end up with new collections: Nigerian market literature, pimp memoirs, Coptic texts from Egypt, books on Eliza Jumel and Aaron Burr. One of the seminal books for me was this one by Robert Farris Thompson. Back then, I was going out with Patti Astor, who starred in Wild Style and started FUN Gallery, which is where Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and all those other graffiti artists first showed. It was an incredible time when people from the Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn, and downtown were all into black aesthetics. But none of us could put it all together the way Thompson did, by charting the influence of five West African kingdoms on Brazil, Haiti, Miami, and New York City.”

———

Art in Transit, Keith Haring and Tseng Kwong Chi

“The year Flash of the Spirit came out, I was putting together the first book Keith Haring did with the photographer Tseng Kwong Chi. They made Keith’s subway drawings a bit of a collaboration. If Tseng wasn’t with Keith when he went out, Keith would call him the next morning and say, ‘I went here, here, and here.’ Then Tseng would go and photograph every piece. They had thousands of photographs, so the first step was editing them down. Dan Friedman, who was a friend of mine and had by that time designed the Citibank logo, agreed to design the book. I didn’t have much of a reputation, and almost no one had heard of Keith, so we also got [the curator] Henry Geldzahler to write the introduction. When it finally came together, Keith inscribed it with ‘For Kurt’ over a picture of him being arrested.”

———

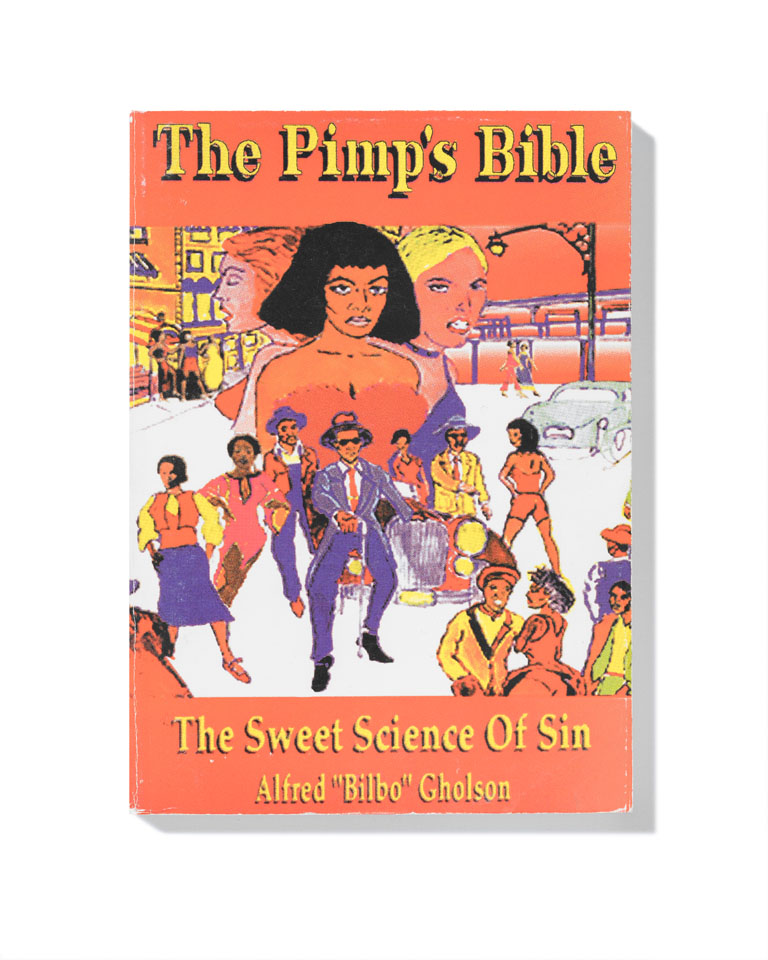

The Pimp’s Bible: The Sweet Science of Sin, Alfred “Bilbo” Gholson

The Pimp’s Bible: The Sweet Science of Sin, Alfred “Bilbo” Gholson

“When you’re setting up a private library, you don’t use the Dewey Decimal System. Instead, you want to strategically place things by location. That’s why I have music books near the record player, books on narcotics near the poetry. I keep my collection of pimp memoirs near the bathroom in case I’m in the mood for something dirty. Back in the day, if you looked closely, you could find books like that at pharmacies and barbershops. They never really made it into bookshops—they were mostly sold through underground distribution. I often compare them to Moll Flanders and the early English novelists of the 18th century, when they were really defining a whole way of writing and making it up as they went along. I remember being on the subway reading Thugs and the Women Who Love Them, and the woman across from me was reading Thugs and the Women Who Love Them Part Two. She looked at me and said, ‘You have to read the second one. The first one is trash!’”