Lou Doillon

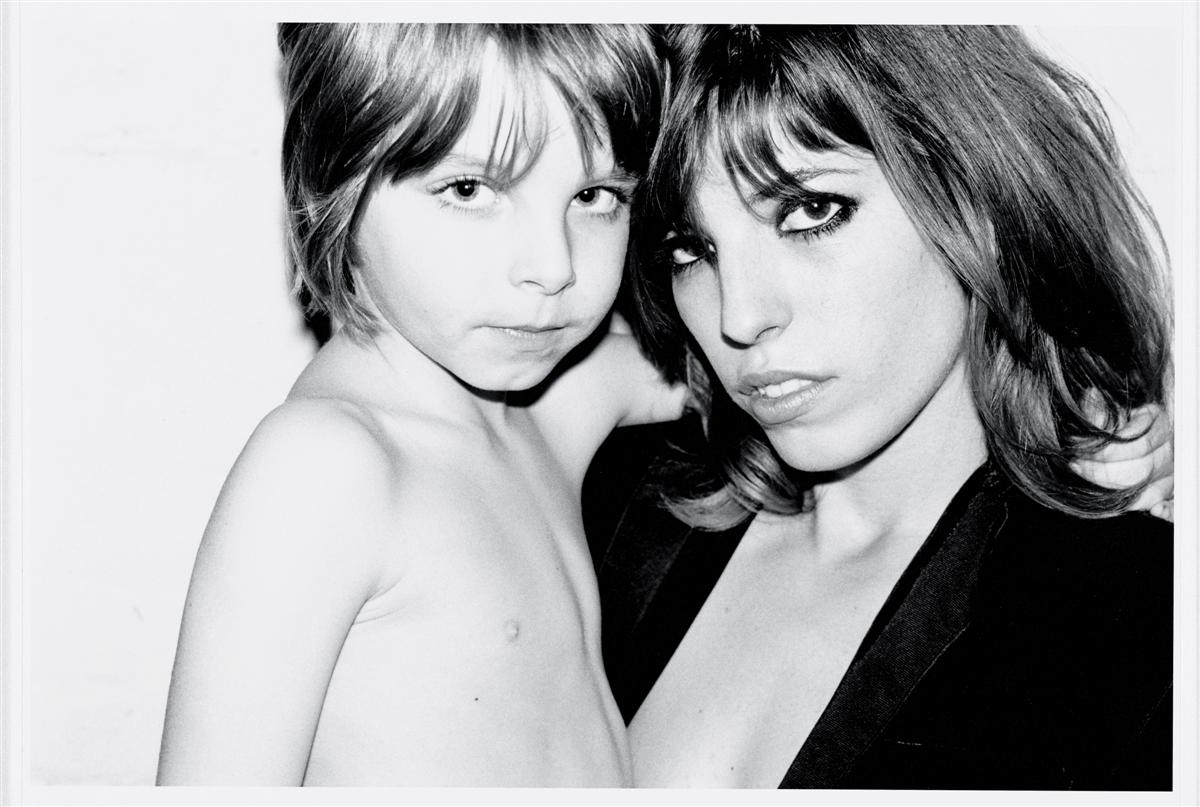

There is little question that Lou Doillon comes from French royalty. Her father is the director Jacques Doillon; her mother is the model, musician, and movie star Jane Birkin; and her half sister is the actress and singer Charlotte Gainsbourg. But this may be the last time a family tree is needed to introduce the 25-year-old Doillon to American shores. Clearly gifted with great beauty, Doillon also happens to be remarkably talented. She has already gone through the model-and-muse track and has increasingly appeared in films and onstage. (Last year she read love letters in a touring one-woman show entitled Lettres Intimes, and she is set to act in the Samuel Beckett play The Image, opening next year in New York City.) Most recently, Doillon has been found camped out in a loft on the Bowery in downtown Manhattan accompanied by her 6-year-old son, Marlowe. Here she’s intent on making her music-a soulful blend of acoustic guitar, ukulele, and singing.

Somewhere between the parties and premieres of the Cannes Film Festival this past May, Doillon’s longtime friend Milla Jovovich sat down with her to talk. The two have a lot in common-acting, modeling, music, motherhood, and fashion design. (Doillon recently began working for British denim label Lee Cooper and will remain with that partnership through 2010; Jovovich continues to crank out sartorial hits with her womenswear collection, Jovovich-Hawk.) They also share a taste for philosophy, literature, and history, none of which would one imagine coming up while the two dress in couture for dinner in the south of France. But Doillon and Jovovich are not your typical partygoers. If they have extra time to talk, they’ll fill it brilliantly.

MILLA JOVOVICH: For Cannes this season, you wore a crown made by Chaumet, and you carried it in a plastic bag. That must feel like a big responsibility.

LOU DOILLON: It was my obsession while walking through the whole airport. I was like, “Don’t forget the plastic bag.” [laughs] If I put my purse down to look at magazines or have a coffee, I was like, “Don’t lose it . . .”

MJ: It gives a whole new definition to digging through your purse, taking stuff out, and putting it on the table to find your lipstick.

LD: In the plane, I put it in the overhead above me, and for the whole plane ride I was thinking, It’s above me, it’s above me. As I was leaving, I was thinking, You mustn’t forget. I started leaving and almost forgot. I had to come back and take the thing!

MJ: Weird accidents have happened in the last few years. I used to travel to Cannes with a little purse that I would carry at all times with about $3 million worth of jewelry in it. I would sleep with it. I would literally have it on my body and never separate from it. Then I went back to the jewelry store for some event and wanted to borrow a necklace. They made me go through so much hell. I said, “You guys gave me, like, $3 million worth of jewelry a few years ago.” They said, “Yeah, but an unnamed star happened to lose hers.” So how much sleep did you get last night?

LD: I guess three or four hours.

MJ: What time did you go to bed?

LD: 8 a.m.

MJ: That’s not really last night.

LD: No, it’s not.

MJ: Well, you did look spectacular. You wore this amazing dress by Armani that was just sparkling, like a mermaid gown, with the obligatory Chaumet crown in a plastic bag.

LD: [laughs] I should have put it on with it still in the plastic bag!

MJ: Exactly. [laughs] The night before, we went to the Christian Dior dinner, where about two hours in, our friend Kris Van Assche, the new artistic director for Dior Homme, disappeared with you. I came with my two friends, and next thing I knew, they’re gone. I went to look for them and couldn’t find them anywhere. Lo and behold, I looked down at the Hôtel du Cap swimming pool, and there’s Lou, in her Christian Dior gown, up to her knickers, walking around the shallows. It was really incredible.

LD: I loved the Cannes security. They said, “Please don’t swim. Please come back tomorrow if you want to swim.”

MJ: Last night you put on your micro-shorts, sans Armani gown, for a swim.

LD: I asked, “Can I go and swim in this gown?” They were like, “No, it’s haute couture.” I ended up in shorts.

MJ: I’ve been listening to the music you’ve been making lately, and I love it. The harmonies and feeling.

LD: I should write that down and make a T-shirt: “Milla said that!”

MJ: It sort of reminds me of a mixture of David Bowie’s Hunky Dory [1971], Violent Femmes, and the Beatles. You’re multitalented. Obviously, you’re also an actress. But what a lot of people probably don’t know about you is that you’re also an amazing painter.

LD: I wish I could be more serious about it. I think there may be something going on there and I should pursue it. I’m very old-fashioned—even with the music. I realize, while I have so much respect for the kookiness of people who go for it, who paint with their eyes closed, I am superclassical.

MJ: Picasso said that he learned to paint classically, and that it was only after learning to paint a face exactly how he saw it that he was able to do what he wanted.

LD: He was famous for the horrible thing he said in a children’s hospital, where some guy tried to show him the drawings of the children. The stupid guy says to Picasso, “Look, they can draw like you.” And Picasso says, “Yes, but at their age I could draw like da Vinci.” In fact, it’s true. It’s like real anarchics, where you have to know the system by heart to start breaking the rules. I do believe that. But I was shocked when I looked at art schools in France. There’s only one left that does anatomy. Now they do video. They do editing. I would go to film school if I wanted to do video and editing. In art school, it’s only new mediums. It’s three-dimensional or computer. I found that shocking. No nudes.

MJ: I’ve always wanted to take a nude drawing class.

LD: The whole point of art school is that you’re going to be able to have nudes all day long and a teacher who is there to move you. It’s great. I did a tiny bit in the one school in Paris, and it was wonderful because you’d have a nude taking a crazy position, and you’d have 10 seconds to do a drawing. Then you’d do a one-minute drawing. At the end of the day, you’d do a 30-minute drawing. What’s great is that suddenly, for the 30-minute session, you’re lost. You’re so used to the one minute that suddenly you’re there with too much time on your hands, and you don’t know which detail you should go for. It’s very interesting.

MJ: I can imagine some of those 10-second drawings might even be the best.

LD: I remember in one school in Paris, you weren’t allowed to touch the paper. You just desired touching the paper, and you had to hold the pen, because it’s all about the moment when you will be able to save up all the energy and focus what goes through your hand.

MJ: You know what? I think that’s an amazing rule for relationships! “I won’t touch you.” It’s all about the anticipation and the desire to touch. We need a little bit of that today. It was sort of the turn-of-the-century, a much more old-fashioned way. The other night, you had that long train on your Christian Dior gown, and we were taking pictures on Wim Wenders’s boat at the preparty for his film, Palermo Shooting, talking about the lost arts-specifically we mentioned when Proust talked about the lost art of a woman picking up her skirt as she walks upstairs. After World War I, that disappeared because materials were too expensive and women pretty much cut their skirts in half. So that gesture is now gone forever, and it is one of the saddest things. When Proust was asked, “What do you miss about La Belle Epoque?” he said, “That lost gesture of the woman picking her skirt up as she walks upstairs.”

LD: And also all the erotic parts of the body, like ankles. There would be erotic moments where you would see half of an ankle, and the dress went back down, and the guys would dream of that ankle for years.

MJ: For money, women would flash their ankles. That’s how you knew a woman was a prostitute. Today, even women who aren’t prostitutes are walking around flashing everything! So it’s very hard to tell these days-especially at Cannes. [laughs]

LD: Especially on the beach-like is that code for something?

MJ: Getting back to your music, I love that there’s such a freedom in your voice-the way you sing, the way you express yourself. I noticed there is something that comes up in your lyrics a lot. I thought it was really funny, because you’re probably the last person who would do this, but wasting time is a recurring theme. Are you scared that you’re wasting time? You do so much. Why do you write about wasting time that way?

LD: I don’t know. That’s been my biggest problem to deal with. My parents were great on many things, but I have a very bad family, timewise. My mother refused to grow from being a child. She is obsessed by her childhood.

MJ: She’s not alone.

LD: But she has it in an acute way. And my father always told me that being a girl ended by the age of 25. Last year I turned 25. I was like, “So, does this mean it’s over?” He was like, “Eh, soon it will be.” Even if it’s a joke, I realize that I always have this in the back of my mind.

MJ: Every joke has a grain of truth.

LD: Yeah, exactly.

MJ: That’s Russian humor. The edge of the sword in your butt. That’s funny-I’m bleeding. Hilarious!

LD: Plus, it doesn’t help that we are three generations of actresses [Jane Birkin’s mother was Judy Campbell, an actress in Noël Coward musicals], who are always obsessed with losing time. But on the other side, historically, women have much more time on their hands than before. It goes together-the more time we have, the more we’re flipping out about how we’ve got to deal with it.

MJ: I’m obsessed right now with Victorian servants. That’s my big thing-buying every book on Amazon.com about Victorian servants and reading about lifestyles, especially of the middle class. The middle class didn’t have enough money, but they would starve themselves just to have servants and starve their servants just to make other people think they had more than they did. These middle-class women literally would call the servant to turn on a lamp, which they could do more easily and time-efficiently on their own, yet they had to have the parlor maid come up three flights to do it. These women went completely bananas because they had so much time on their hands, and unfortunately, because of the repressions of the day, they were not supposed to do anything. But, you’re right, there is a paradox today-the more you do, the more you’re scared to waste time.

LD: In France, I was raised with this terrible saying: “If you do two things, it means you don’t know how to do one well.” They say that all the time, so it was hard for me to get involved in different careers. I felt that everyone would be so angry when I started to do fashion or when I wanted to do acting . . . Music, for the moment, has been this hidden thing for me. For the first time, I am master of something. I am not used by someone else, like in movies or pictures, where you always have the happiness or disappointment of knowing it’s you seen through someone else’s point of view. You go to see a film and half of the pretty scenes are not in it-the ones you liked. Living with this frustration all the time, suddenly music came as the best thing for me at home, where no one can tell you anything. Now I am really opening up to Chris [Brenner, who works with Doillon on her music]. For years I was so closed, wanting to do it exactly like I had it in my head, because this would be the only place that was superpersonal.

Music, for the moment, has been this hidden thing for me. For the first time, I am master of Something.Lou Doillon

MJ: You don’t want to change anything. It’s like a first-time filmmaker who makes his three-and-a-half-hour manifesto-

LD: Right! [laughs]

MJ: And you can’t cut one scene, even for the benefit of the film, because “It’s my first movie!”

LD: Singing is the rawest thing. Having been naked in films or naked in photo shoots, it’s nothing compared to singing. It’s absolute nakedness. You are stripped bare! It’s very strange. Acting seems much easier, in fact, because you are putting on a costume–whereas here you are taking everything off.

MJ: I don’t mean to harp on this thought, but do you feel that, in some sense, the people who do the best are the ones who are the most scared of wasting time?

LD: I think so.

For the last few years especially, i don’t know why …I wake up thinking, ‘this is not going to go on forever. Take it for what it’s worth.’Lou Doillon

MJ: I see a lot of people, especially in Los Angeles, who do nothing. They’ll go get their hair blow-dried three times a week, they’ll go get their nails done, they’ll go shopping all day, and it feels as if they don’t have any conception that they’re going to die!

LD: Yes. Completely. It’s true that it is a real, real fright. Sometimes it’s a positive fright, and sometimes it’s a negative one. For the last few years especially, I don’t know why, maybe since Marlowe was born, I wake up thinking, “This is not going to go on forever. Take it for what it’s worth.” I don’t need to be thinking every moment is the last moment, because I think I would become mad if I saw every moment like that. But there is a thing where I get scared watching other people, and really realize, My God, it’s going to stop. Sometimes you feel that people have 19 jokers in their back pocket and, because of the way they’re living, you’re like, Do you know that this is not going to happen over and over again forever?

MJ: In Palermo Shooting, there’s this line about how you have to take life really seriously. Don’t take yourself seriously, but take life very seriously every single day, because it’s not going to last.

LD: That’s what’s beautiful about it. And Dennis Hopper’s character is absolutely right when he says that the only reason life has value is because of the ending, because of death. It’s like jealousy. I was with someone who was very, very jealous, and I was like, “There is no faithfulness when being at home.” But if you’re out in the world, like at a place like Cannes, if you’re faithful here, then we can start talking about faithfulness. In Paradise Lost, there’s a wonderful sentence when one of the angels says to God, “How is it possible that you could make humans and angels turn against you?” Talking about Satan, he says, “Why did you put it in him that he can turn against you?” God says, “Because, otherwise, you would have no Heaven.” If he had created us to be in love with him, obviously, then it would have no value. Hence, it’s true that the biggest value of life is that it’s going to stop. I was thinking when I was in New York the last time that all that we see that has importance is man-made. It isn’t nature-made. And when I was looking through the window, looking at New York, I was so moved by humanity’s desire for immortality-because that’s what it is. I saw Julian Schnabel’s big pink building in the West Village, and it is reaching for the immortal. That building is like Citizen Kane [1941]. The first word that came to my head was “Rosebud.” I just looked at that thing, and I was thinking, It’s charming to see how we are convinced that we can become immortal-because that’s what every big building in New York is about. Like it’s going to be there forever.