Punk May Be Dead, But Legs McNeil Sure Isn’t

Here is a brief list of things Legs McNeil hates: needles, The Grateful Dead, the Hardy Boys series, heroin, Robert Christgau (who he claims never truly understood punk), and reality TV. Here is a slightly longer list of things Legs McNeil likes: Eggs Benedict, Cream (the band), Gary Oldman, and Chloe Webb’s performances in Sid & Nancy, The Dictators, noir, lavish if now-extinct press parties funded by record companies, Hubert Selby Jr.’s Last Exit to Brooklyn (originally recommended to him by Roberta Bayley, who informed him that anyone who hadn’t read it was an asshole), and the history of the 101st Airborne. Add to that list the Chateau Marmont, the spot where we’ve chosen to meet and the only hotel with a claim to fame that involves John Bonham riding a Harley through the lobby where F. Scott Fitzgerald allegedly suffered a heart attack decades earlier. McNeil knows the joint; he and Dee Dee Ramone lunched in the hotel restaurant the day of The Ramones’s final show in 1996. McNeil doesn’t live in Los Angeles; he’s only passing through, staying in a smoking room in the Standard Hotel. Cigarettes are, after all, his last remaining vice, or at least they were. He quit this past Thanksgiving.

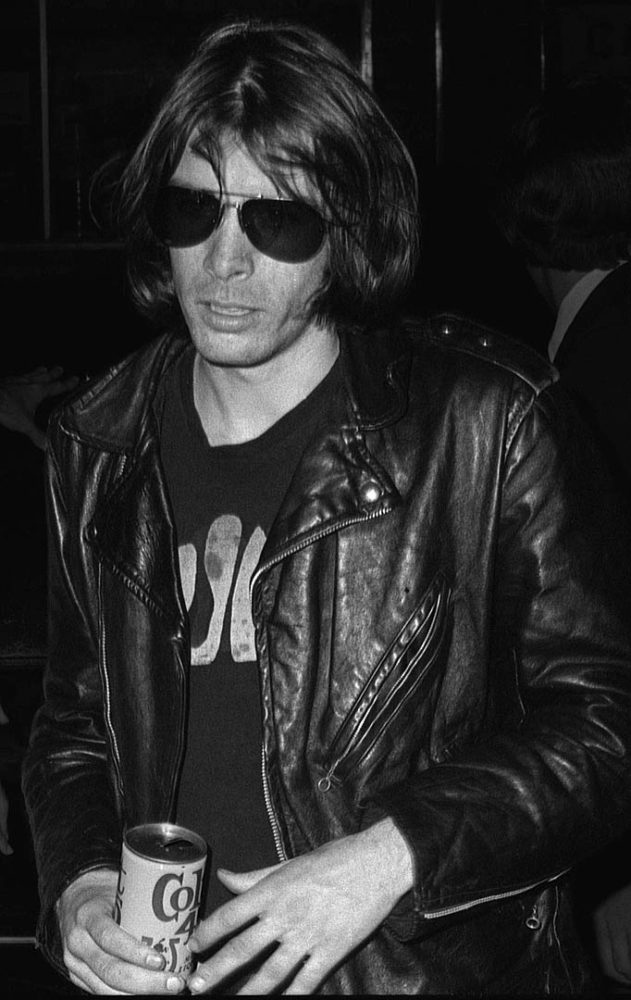

McNeil occupies the oxymoronic status as an underground icon, thanks in part to his role as co-founder of PUNK, the irreverent ‘70s magazine that chronicled the New York punk scene and popularized the term ‘punk.’ (The title was McNeil’s idea). Together with John Holmstrom and Ged Dunn, McNeil ran the magazine out of the Punk Dump, a former auto parts store spitting distance from the Lincoln Tunnel. McNeil was the publication’s “resident punk”—a role that involved embodying the zeitgeist as he saw fit, often by “getting drunk every night and fucking a different girl.”

These days, McNeil functions as a journalist, classic punk’s unofficial archivist, and one-half of the creative team that produced the indispensable oral history Please Kill Mein 1996, which singlehandedly spearheaded a genre in music journalism. He and his writing partner, Gillian McCain, are now working on their second major oral history collaboration, a chronicle of the 1969 Manson Family murders. McNeil was 13 that summer, keeping busy selling weed to Canadian tourists in Mazatlán, Mexico while his surf bum older brother sought out the perfect wave. (Said brother had watched the 1966 surf doc classic The Endless Summer, and it inspired him enough to temporarily relocate the family.) “It was just wonderful. It was one of those summers where you start playing with matchbox cars and by the end you’re smoking cigarettes and you’re a little thug,” says McNeil. Back home in Cheshire, Connecticut the following winter, McNeil slipped a just-published paperback copy of Susan Atkin’s testimony called The Killing of Sharon Tate under his jacket at the local Morton’s Pharmacy. He still has it.

Granted, growing up skinny and weird in Cheshire was a desperately bleak state of affairs. McNeil never knew his father, who died of stomach cancer when he was two months old. His maternal grandfather shot himself; his maternal grandmother committed herself to a mental hospital. Not one to be outdone by the woes of others, McNeil is extremely dyslexic—“I have to block print everything,” he says–and was born with one leg significantly longer than the other (hence the nickname “Legs,” given to him by Holmstrom). At 16 he underwent surgery to shave two inches off the longer femur and spent the recovery period in a morphine haze that would later turn him off of heroin forever. But he’ll try anything once: “I shot up with [Alice Cooper’s guitarist] Glen Buxton and went to the Mudd Club and relived my entire leg operation. I said, ‘Fuck this!’ I couldn’t even get drunk.”

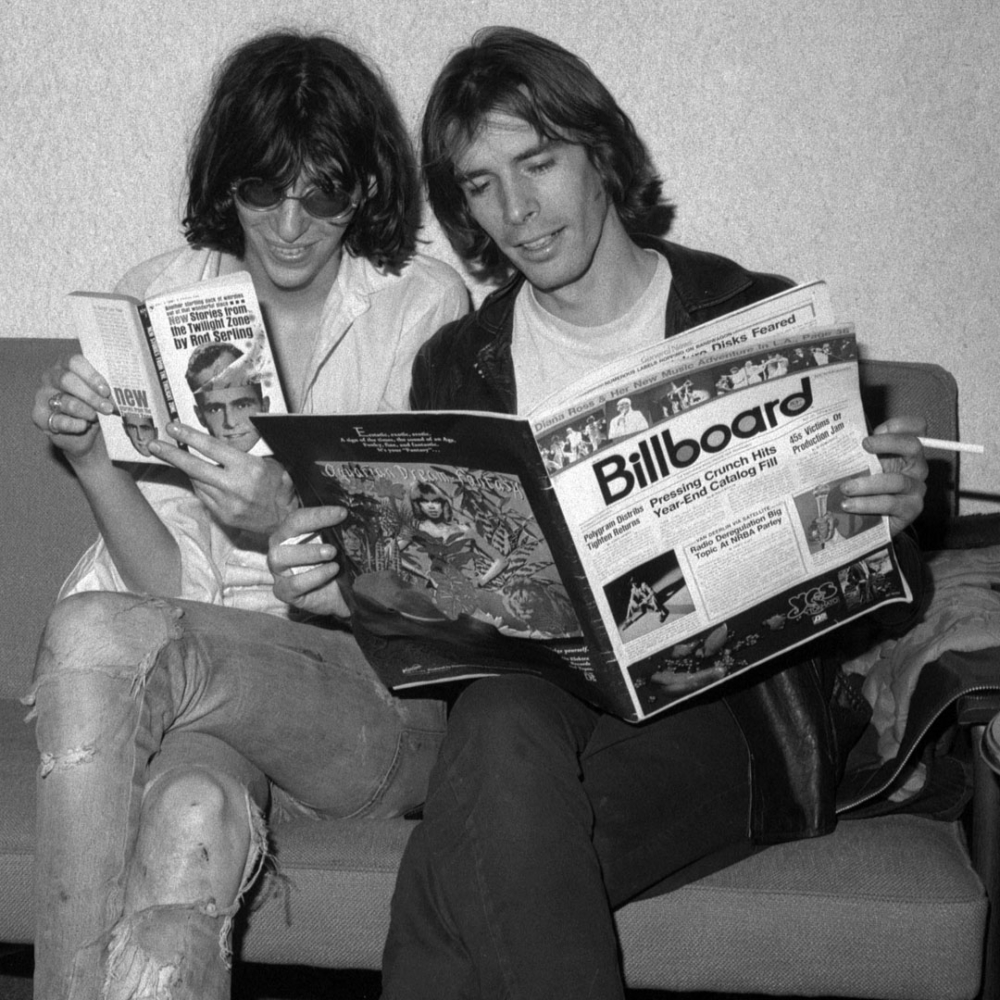

Not being able to get drunk is no small feat for McNeil, who started drinking properly at 13. He hated jocks and wouldn’t play sports, instead spending afternoons catching turtles and snakes in a nearby swamp. In high school, he became friends with Holmstrom, who later relocated to New York to attend School of the Visual Arts. (He taunted McNeil from afar by sending letters boasting about how he’d become a millionaire first.) Eventually McNeil dropped out and moved into Holmstrom’s Manhattan apartment, agreeing to help Holmstrom write comic strips and split the $150 payment per strip. “I’d get $75, which bought a lot of cigarettes and beer in those days. That’s all I cared about,” he says. McNeil and Holmstrom decided to start PUNK prior to ever stepping foot in CBGB’s, and when they finally did, they showed up wearing Creem t-shirts and denim jackets. The Ramones were playing. Lou Reed was in attendance. “They all came out and played the wrong song, and they threw down their guitars in disgust and marched back. We’d never seen anything like this,” he says. “I was like, ‘Who the fuck are these guys?’ And then they came back and went into ‘I Don’t Wanna Walk Around With You.’ I was like, ‘I’m home.’”

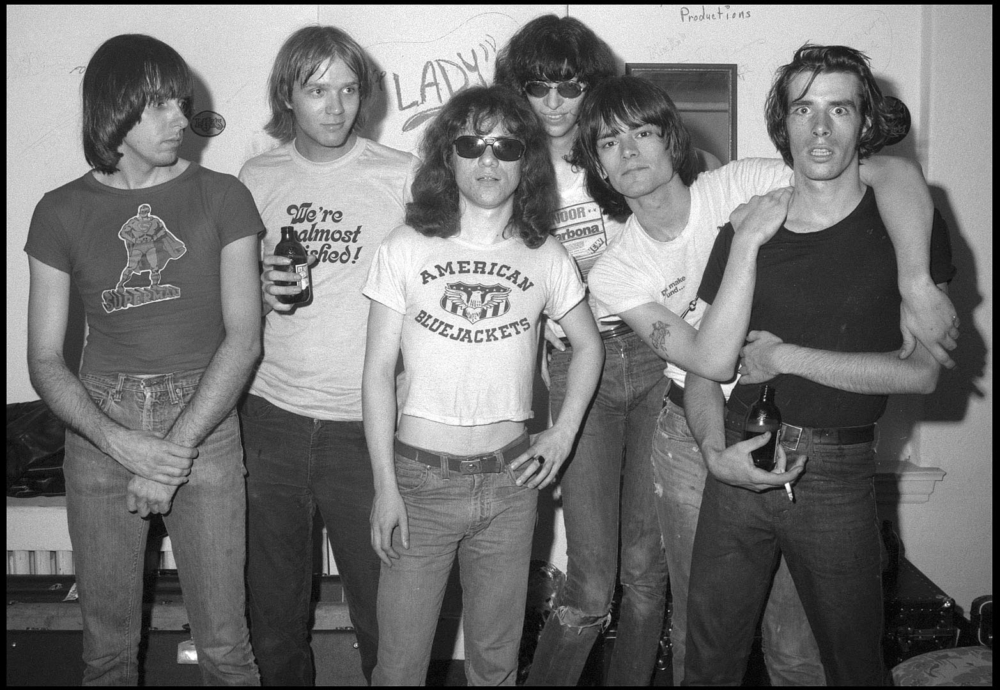

The rest is punk (and PUNK) history. PUNK’s debut cover feature was a comic-ified interview of Lou Reed conducted by McNeil and Holmstrom at CBGB’s. McNeil wrote for the magazine and starred as recurring character in the comic strips—“I started my career off as a cartoon character,” he muses. McNeil quickly fell in with the Ramones, especially Joey and Dee Dee. “Johnny was a thug,” he remembers. “It wasn’t pretend with the Ramones. Dee Dee really was crazy. Joey really did hear voices. What was great about it was that Tommy saw the brilliance of it when they were writing ‘Judy is a Punk.’”

As such, McNeil has plenty of punk stories: he was in the van the night Johnny called Dee Dee’s then-girlfriend Connie Gripp a pig, and Dee Dee responded by pulling a knife. (Gripp would later famously shank Dee Dee with a broken bottle upon finding him in bed with Nancy Spungen.) He occasionally answered calls to CBGB’s phone booth, the majority of which were girls asking for Dee Dee or Johnny Thunders. Danny Fields, who managed the Ramones and signed MC5 and the Stooges to Electra Records in the same phone call, along with journalist Lisa Robinson, attended PUNK’s 1976 Christmas party, which was remembered for its tree decorated with cigarette butts and topped with Debbie Harry’s centerfold. Since the Punk Dump lacked a shower, McNeil would bathe at Spungen’s place. When Sid Vicious was arrested on suspicion of murdering Spungen—McNeil doesn’t think Sid killed her—he refused to be interviewed.

There are longer stories too, like the time he went to the Sex Pistols’s final show at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom in 1978. He hadn’t planned to attend; he was staying in L.A. at the Tropicana Motel with The Ramones and The Runaways. Holmstrom called him and told him to get to San Francisco for the show. “I said, ‘The fucking Ramones will kill me if I say I’m going to the Sex Pistols. They’re already pissed Warner Brothers is spending all their promotional money on the Sex Pistols,” McNeil says. He went anyway. He spent most of his time in San Francisco floating in a hotel bathtub with the receptionist from Playboy and ordering crab sandwiches to the room. When he eventually made it to the gig and got backstage using Bob Gruen’s photo pass, he watched Annie Leibovitz, then a staff photographer for Rolling Stone, try in vain to wrangle Sid Vicious. “It was very slapstick, very Chaplin-esque,” he says. That’s the last amusing part of the story. “Sid had the roadies grab four girls out of the audience. Sid looked over at them and said, ‘Who’s going to fuck me tonight?’ And one of the girls was really serious, and she looked at him and said, ‘Don’t I get a kiss first?’ I thought it was the most heartbreaking moment of rock ‘n’ roll.” McNeil didn’t bother to stick around. He filled his jacket with bottles of Heineken from an ice-filled dumpster and left.

Strapped for cash as the ‘70s wound to a close, McNeil quit PUNK and sold an interview with Norman Mailer to High Times after Holmstrom refused to pay for the piece. He spent the ‘80s on deadline for SPIN and drinking heavily, at least until the hangovers became brutal enough to make sobriety appealing. Towards the end of the decade he met Gillian McCain, and the pair bonded over their shared admiration of Jean Stein and George Plimpton’s oral history Edie. Around the same time, he sat Dee Dee down in front of a tape recorder. Dee Dee carried on long enough to fill ten 90-minute reels.

McNeil’s original plan was to write Dee Dee’s memoir as an oral history, but McCain insisted there was a more expansive story about punk waiting to be told. McNeil suggested they do it together, and Please Kill Me arrived in 1996. It has since been translated into multiple languages and inspired multiple imitators. (“They all suck,” says McNeil. “People don’t know how to cut and edit.”) In oral histories McNeil found his format of choice, and in 2006, he published The Other Hollywood: The Uncensored Oral History of the Porn Film Industry. Now, he’s focused on the expansive oral history of the Manson murders. Despite having conducted some 200 interviews, McNeil says the scene coinciding with the murders is surprisingly small. But there were only so many hippies, and their priorities were rather uniform: they wanted to “smoke dope and fuck and listen to rock ‘n’ roll. Things haven’t really changed that much.”