Jonathan Galassi Found His World

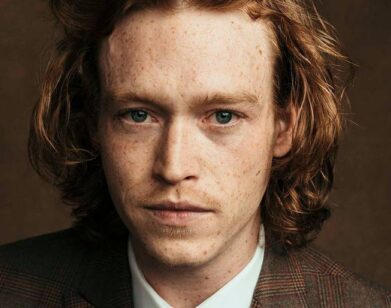

PHOTO BY CHRISTOPHER GABELLO.

The last stanza of the last poem that appeared in Jonathan Galassi’s 2000 book of poems, North Street goes like this: “there’s no motion, no commotion/ only birdsong breaking through/ In the world I don’t believe in/ nothing’s keeping me from you.”

A lot has changed for the poet in the interim between North Street and his most recent collection, Left-Handed, out from Knopf this week. There has been both motion and commotion: The 62 poems that comprise Left-Handed chart the disintegration of the poet’s marriage, his coming out as gay, his pursuit of a younger man who does not return his affection, and his continual search for the right missing piece.

In the process, Galassi has conceived of a world he does believe in—or at least a world where it’s possible for him to believe in himself. Now he just needs the “you.” The 62-year-old writer, who is also the president and publisher of Farrar, Straus and Giroux and serves as the Honorary Chairman of the Academy of American Poets, didn’t just write a poetic follow-up for his third collection—he wrote a poignant, piercing, and very private falling out, down, and over.

“Time is short,” he writes in the poem “Once,” “you have to live it.” Galassi’s style has always been imbued with a dark, romantic edge, and his particular imagistic tic leans toward nature. It’s a credit to his style and to the confidence of his voice that both hold up beautifully in Left-Handed when he dives straight into the heart of Manhattan (“the rough-/ diamond city spread-eagled be- / low”) and straight toward the heart of a fellow named “Jude” (“I / can still believe I’ll be / rich in another sun”).

Galassi’s verses can be pithy and playful, and it’s a joy to watch the flame light so blue and so high for love in these poems. But his most haunting poem, the appropriately named “Ours,” reveals what is lost in all of this new, boundless gain: “hours were ours the/ walks the silent drives the si- / lences unspoken love the lacks / the guilt the missing the alone- / ness what we couldn’t do the / what we didn’t say the things I / couldn’t do the one I couldn’t / be and wanted to and didn’t is / our too.”

I visited Galassi at his FSG office just off Union Square in early March to talk poetry. Naturally we touched on the greats: Bishop, O’Hara, Sexton, Lowell, and the left-handed one himself taking a minute out of his busy day.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: Usually when I read from a book of poetry, I just open to a random page. I never start at the beginning and go from front to back. But your new collection has a narrative that unfolds over the course of the book. It’s actually made me wonder: have I been reading poetry books wrong this entire time?

JONATHAN GALASSI: I think this one is more structured. There are many different ways of putting together a poetry book. This one does tell a story. My other books didn’t in this way.

BOLLEN: Did you set out to create a story when you started writing these poems?

GALASSI: No. But my poems are always about my life in one way or another. The first part of the book was a continuation of the poems I had written in my last book, North Street, which was set up in Connecticut.

North Street was one of those poems about starting again at 50. And Left-Handed is about starting again, too. I wrote the first poems in Left-Handed in the same place. Someone told me, “Oh I see you write in the summertime because there’s a lot of summer imagery.” That’s because I wrote it in summers. That’s what I did on my vacations. I wrote poems.

BOLLEN: I noticed the summer imagery. Arguably you’re a nature writer, but there is a sharp detour into the urban about a third of the way through the book.

GALASSI: Yeah, this book is all about the incursion of something into a settled life. That happened here. There are all sorts of dichotomies in the book and one of them is city versus country.

BOLLEN: Was it a challenge to put this book out because it was so personal?

GALASSI: Yes, it was a challenge. There have been a series of challenges in my life, which have changed my life, and that’s reflected in my writing. It’s one thing to live those things, another to write about them, and then it’s another to publish them. I felt that the changes I made in my life were necessary and right for me. The book is a story about an aborted relationship, but it’s also about how that relationship liberated me. It brought me into closer contact with myself. The second part of the book is about this frustrated love affair, or infatuation, since it was non-happening. The third part is about the aftermath, and it’s about loose ends. It’s about other relationships and about looking backwards and about divorce. It’s about guilt. If the middle part is the tapestry, the third part is about all the different threads that come out of it.

BOLLEN: As you were experiencing these life changes, was poetry a sort of therapeutic safe haven? Did you look to poetry to make sense of what was going on?

GALASSI: A lot of those poems were actually written for the other person, “Jude.” Did you notice in some text, it says “lost”? It’s because some of those poems really were lost.

BOLLEN: Do you mean literally lost?

GALASSI: They were lost, by Jude.

BOLLEN: Wow. You know, you should always keep a copy of your work, right?

GALASSI: But they were written as offerings. This was not a literary project. This was a life project. It wasn’t conceived as a book. This was what was happening.

BOLLEN: There are also poem fragments that are printed in gray.

GALASSI: That’s what I can remember of those poems.

BOLLEN: And in the poem “The Last Swim of Summer,” you have a footnote clarifying that it wasn’t actually the last swim of summer. That another swim “came weeks after, it was so warm that fall.” I love correcting the facts in poetry. Poets are notoriously hyperbolic. Or romantic liars. They usually aren’t ones to trip over stubborn details.

GALASSI: They’re mythmakers. I did that because it was supposed to be funny.

BOLLEN: It does take a pickaxe to the grandiose feeling.

GALASSI: Here’s this lyric about loss and about not saying goodbye. And then I’m sort of saying, well, it wasn’t actually that way. It’s sort of anti-poetic in that way.

BOLLEN: Swimming is an image you return to a lot. So is frequent flying.

GALASSI: Yes, because that metaphor of the flyer starts with the high-flying Jude. That’s one of the metaphors of him.

BOLLEN: Have you always used poetry to work out your romantic side?

GALASSI: I think poetry was always where I went to deal with my deepest feelings.

BOLLEN: I wrote a lot of poetry when I was in college. And I often wondered why I was more attracted to poetry in those years than to fiction.

GALASSI: Because you were miserable. [laughs]

BOLLEN: Yes. I truly was. But I also think I was much more of a closeted character in those years. And one of the great things about poetry is the pronoun “you.” The “you” is so liberating because it shields the writer from identifying the subject. It’s great for gay writers because you don’t have to use a gender pronoun. But I guess what I mean is, poetry is a terrific way to tackle feelings and also to camouflage them. You use “you” a lot in your poems, as well as so many great poets. Do you feel that poetry reveals and disguises simultaneously?

GALASSI: I don’t think there’s any hiding of the sex of the person. At least not in this case. But I do think poetry can be very naked and clothed at the same time. It’s very specific, but it’s also universal. The specific story of this particular poem can also stand for something in the experience of the reader, or a general experience, and that’s what poetry tries to do.

BOLLEN: Of all the interesting pronouns in Left-Handed, I found the poem “Ours” to be one of the most powerful. It tests the durability of the pronoun “ours,” which breaks down.

GALASSI: That’s to my wife. But that’s really true. There’s no “we” with Jude. That’s part of the story too. The third part is trying to work your way towards that, towards somebody else.

“Ours” was probably the last poem I wrote for the book. That was looking back at it and trying to make sense of the whole thing and honor it. It was a very big relationship.

BOLLEN: I wanted to ask you about Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop, who you studied with at Harvard.

GALASSI: I was very lucky to have them, especially Elizabeth Bishop. Robert Lowell was kind of intimidating to me. Very Olympian. He wasn’t so accessible. He taught a poetry class. Elizabeth, on the other hand, I became really close to and adored. She was like a grandmother. She was a very formal, reserved person, but we really connected. I loved her.

BOLLEN: Did the camaraderie extend beyond college?

GALASSI: I saw her for years after that. She was a friend. I was so awed by her. I loved her poetry. She was published by FSG then. And now here I am at FSG and there’s Elizabeth Bishop’s National Book Award [Points to award framed on his office wall]. There are some sacred objects here.

BOLLEN: That’s the book I read when I came to discover her poems as a kid.

GALASSI: She was a New England lady. She was a lot of other things too. But, as James Merrill says, she carried out a life-long impersonation of an ordinary woman.

BOLLEN: [laughs] That is a great line.

GALASSI: She was a natural, which was one of the great things about her style. And she was an ideal for me in many ways. She was a great teacher. Some of the other kids thought she was too old-fashioned. She did inspire me ethically, and her insistence on clarity, honesty, simplicity, all those things, mattered to her.

BOLLEN: What were your poems were like in college?

GALASSI: They were college poems. She had us do imitations of other writers.

BOLLEN: I think all of my poems in college were imitations of other writers. Only that wasn’t the assignment.

GALASSI: These were supposed to frankly imitate. Then she would have you turn prose into poetry. They were great assignments.

BOLLEN: So you stayed in touch with her until the end of her life?

GALASSI: I did. After college, I went to England and studied for a couple years. Then I moved to Cambridge and she was living there. She was still teaching at Harvard. Then, I was sent down to New York in ’75 and she died in ’79. I have a lot of letters from her.

BOLLEN: Do you see a difference in those iconic poets of the mid-20th century standing very tall in literature and the poets of today? Is the mythical status of the poet different now than it was then?

GALASSI: The thing about poetry today is that there are so many different things going on. On the one hand, you have someone like Ashbery, who really loved Bishop, and you could say that he’s the continuation of that line of the great poet. Although he’s much more experimental. Then there are all these poets in their 20s and 30s, and a lot of them sound alike to me. I can’t make sense of some of them. But we’re always discovering new people that we’re excited about. I think the process of poetry continues. The poets of the future will decide who the poets of now are. The people who are read in the future are the canon. So I’m still a big believer in the process. Poetry is an incredibly active and lively art today.

BOLLEN: I had a poet friend tell me, “Oh you’re so lucky you’re writing a novel because, with fiction, there’s commercial success involved.” I thought, no, you’ve got it backward. It’s so awful to write novels because there is commercial success involved. You register yourself as such a failure when there’s this money yardstick telling you that you didn’t earn enough or sell enough. I think there’s something liberating about poetry primarily because there is no chance of commercial success.

GALASSI: Many poets have said that. [Eugenio] Montale, who is a big hero for me, said all it takes to write a poem is a pencil and a piece of paper. The fact that it’s not commercial is its saving grace. It’s really about needing to write it. I agree with you. I think it’s a wonderful thing. It’s not a way to make a living. It’s a way to live.

BOLLEN: Did you find that when you got out of school and you entered publishing that being an editor was compatible with being a poet? Or were those completely separate ventures?

GALASSI: No, they weren’t separate. I wanted to be involved with literature. I certainly wasn’t going to be able to write for a living, and I didn’t have enough confidence in my talent to think that I should be just doing that. Publishing seemed like fun to me—to be involved with writers. And it did turn out to be. I thought I’d try it, and I’m still trying it, 40 years later.

BOLLEN: Were you writing poems in your early years in publishing?

GALASSI: I was slowly writing. I didn’t publish my first book until the late ’80s. I did a lot of translations. I started working on Montale’s prose and then on his poetry. I sort of backed into publishing, the way I backed into everything. I always say that. I was always writing. Ever since high school. But I have had my ups and downs in publishing. I was fired from Random House.

BOLLEN: Getting fired can be one of the greatest things that a person can experience.

GALASSI: It can! It’s the best thing that ever happened to me. At the time it was painful and difficult, but FSG just turned out to be the right place for me. It’s been wonderful ever since. I’ve been here 25 years now.

BOLLEN: You edited a lot of poets in the ’70s, correct?

GALASSI: They let me start up a poetry series at Houghton Mifflin. I said, “We should do a new poetry series,” and they said, “Fine.” And we did.

BOLLEN: One of the poets you worked with was Anne Sexton, at the end of her life. I think it was Robert Lowell who said something about how her late work suffered because she either got too good or too bad at writing poems.

GALASSI: I don’t remember the quote. But she was fascinating. Her death was, in a way, the end of the confessional period. It was wonderful and lucky for me to catch a glimpse of that.

BOLLEN: You came to New York in 1975. I read in an interview where you said you felt like you had just missed a big cultural moment in New York. I feel like everyone who comes to New York always feels like they’ve missed something.

GALASSI: It was just after the whole New York School moment.

BOLLEN: I was lucky enough to study under Kenneth Koch in college. His class, among other delights, was basically a series of anecdotes about Frank O’Hara. It was worth the tuition to hear those stories.

GALASSI: It wasn’t just the poets, it was the painters—the poets and painters together. I felt like when I came in ’75 that I was coming onto the tail end of a really great moment in art in New York. There had been many other great moments that have happened in art since. Balanchine was still around, for example. But if you’re a poet, there’s something about the romance of the New York school, all those people being poor together downtown. It’s pretty magical. The place you can still breathe the air of the New York School moment is the Tibor de Nagy Gallery.

BOLLEN: If you came in the mid ’70s, I suppose you were arriving at the moment of the language poets.

GALASSI: I was never drawn to the language poetry. And I don’t know if they were so New York-centered. Charles Bernstein is a friend of mine, I knew him in college. But he’s not really hardcore language poet. He’s a theoretician of language. To me, language poetry is sort of like Dada. Once you’ve seen it done, you don’t need to see it done twice, you know. It doesn’t have any intrinsic poetic interest for me.

BOLLEN: Do you find it hard to wear two different literary hats? On the one hand, you’re a publisher and editor. On the other, you’re a poet. It’s living two very separate lives in the same system.

GALASSI: I would say that one flows into the other. And I only publish a book of poetry every 12 years or so. But I would say that my own writing is quite out of the fashion lines of poetry right now.

BOLLEN: Really? How so? Because it’s autobiographical?

GALASSI: It’s not the content. It’s style I’m talking about. It’s a little more traditional. In this book I kind of broke that up by changing the lineation and stuff. I think probably the poets that I feel closest to stylistically are poets like [James] Merrill, people from another generation. At the same time I really don’t want to be in the boat with the new formalists. I think they’re very narrow and they don’t feel alive to me. I don’t know.

BOLLEN: Throughout your poetry, there has always been an obsession with time and age.

GALASSI: To be bald about it, I think that my earlier work was probably more concerned with time passing because of unfulfilled desires or yearnings. Now, I feel younger than I felt when I was a young old man. Now I want to live as long as I can. We’ll see what comes out. That might not be such a theme in my poetry from here out.

BOLLEN: This may be a warped question, but now that you no longer have all of these bottled-up unrequited feelings, are you less inclined to write poetry?

GALASSI: No. I’ve been writing a lot lately. That’s like people who are afraid if they go to psychoanalysis that it will kill their talent. That doesn’t happen. But I’ve been writing a lot lately, for me.

BOLLEN: How does a poem come for you? Is it an image? A line? A matter of forcing yourself in a chair and just putting words down?

GALASSI: It starts with words. A line. Of course, that line is about something. I just visited a friend of mine in the Dominican Republic and I started writing a poem about him. I’m dying to write it. I want to send it to him.

BOLLEN: I love how you use poetry as correspondence.

GALASSI: I do. I was asked recently to write something about photographs that a friend of mine did. I found that inspired me to write something that really interested me. So assignments sometimes are good too.

BOLLEN: Obviously your poems are very personal. Do you consider yourself a confessional poet? I’m confused by what the term “confessional poet” even means any more.

GALASSI: I think the people who wrote confessional poetry didn’t like that title. They would reject it as being reductive. Who are the confessional poets? It was Lowell, Sexton, Sylvia Plath…

BOLLEN: What about O’Hara? He could, in some way, be read as quite confessional.

GALASSI: O’Hara is much more joyful about it. He’s not anguished. He’s happy. He’s about asserting happiness and normality and health in his life. That is extremely winning I think. Although he talks about pain and other things too.

BOLLEN: Even in his neurotic lines—”I don’t know the people who will feed me”—have great warmth and exhilaration in the lines.

GALASSI: They are “I do this, I do that” poems. It’s about daily-ness. There’s an acceptance of life despite everything. So I wouldn’t call him confessional. I would call him… “advertisements for myself.”

BOLLEN: He fully embraces it. The whole cultural, social, New York romantic swirl.

GALASSI: It’s sort of like saying, “I’m here, I’m queer, get used to it.” The so-called confessional poets are existential. They chart their existential dilemmas of life in a darker, more northerner way. You could almost say O’Hara was a reaction to them. He was the un-confessional or the non-confessional poet. I think there’s no denying that my book was influenced by Robert Lowell’s poetry. He’s not my favorite poet, but he wrote about his life in a very naked way. It’s definitely a book about a conversion. It’s about a change. That’s one of the things it draws from.

Actually, Montale’s poetry is a much more direct poetry for me than Lowell. He called his work an autobiographical novelette. You may not know Montale’s poetry. The center of his work is his love for this woman Clizia. She was actually an American Jewish woman who lived in Italy and had to go back in 1938. It’s all about her absence, and he idealizes her. There’s a huge tradition in Italian poetry going back to Petrarch and Dante about grieving an absent woman. He uses that whole mythology and updates it in terms of his own life.

I think that’s much more at the core of this book. This book didn’t start out as a book. It started out as a series of poems to be given to Jude. They added up into something eventually.

BOLLEN: Finally, I wanted to ask about the title, Left-Handed. Obviously it’s from a poem, but you are actually left-handed?

GALASSI: I am left-handed. It wasn’t the original title. It was called The Crossing for a long time. But I thought that was too bald. But I think that poem, that’s probably the most psychoanalytical poem. Left-handed is a metaphor for gayness.

BOLLEN: And the way they try teach you to write right-handed as a kid.

GALASSI: Right. My parents knew that I was left-handed and didn’t try to make me write that way. But, the implication is, they did try to make me do other things. That’s the subtext. Maybe, although not consciously, I wanted to mold myself to be what I thought they wanted me to be. But if you’re left-handed, you’re left-handed. You can’t do anything about it. I think it’s a good title for the book.

Christopher Bollen’s first novel, Lightning People, came out in 2011. He is the editor at large at Interview.