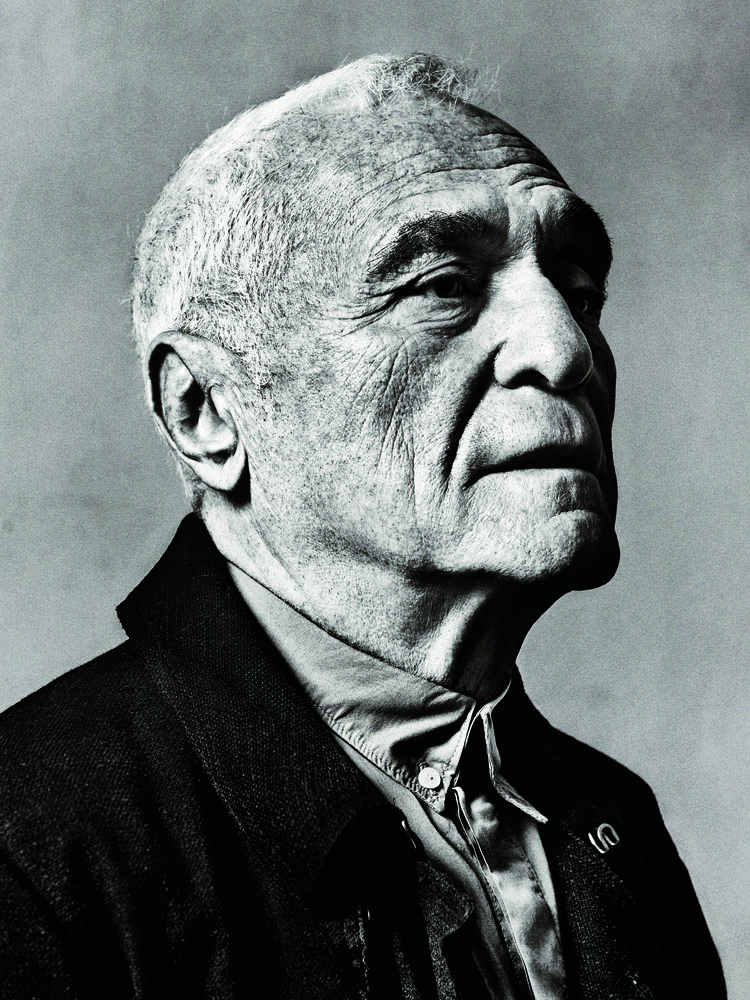

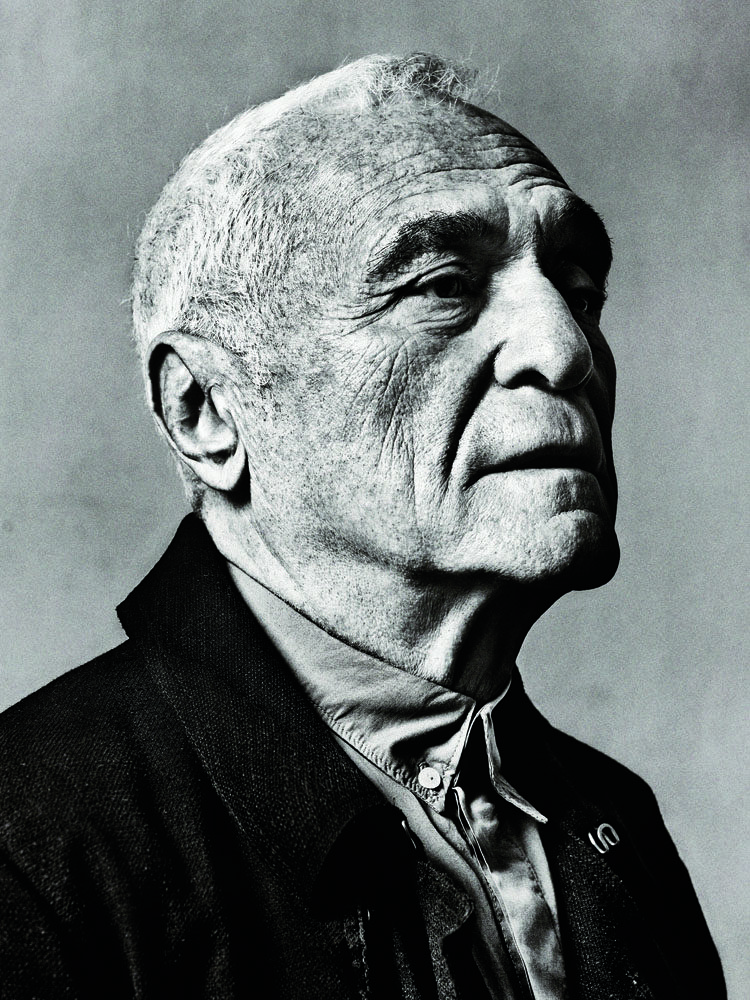

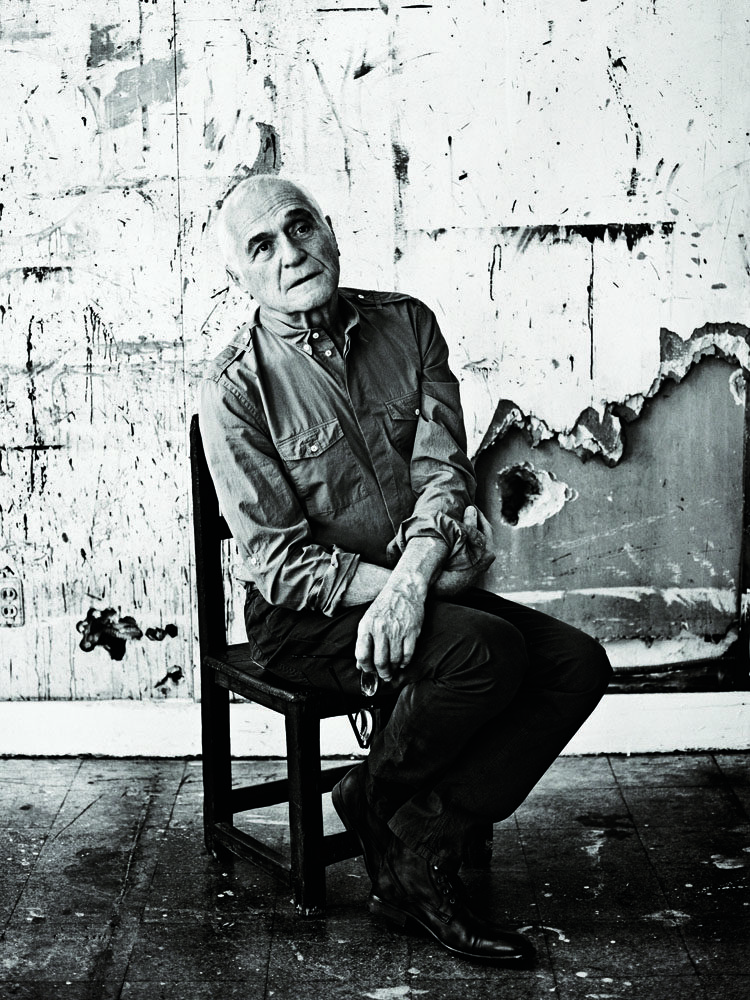

John Giorno

If there is a spiritual shrine in New York City devoted to the downtown art and literary worlds of the past half-century, it exists in a building below Houston Street on the Bowery, in the three lofts owned by poet, performer, painter, and legend John Giorno. Giorno has lived in the building for almost five decades and divides his life among its floors: one for writing; one for painting; and the third, “the bunker,” which originally was home to his longtime friend William S. Burroughs, for, among other life-sustaining acts, dinners and occasional Buddhist prayer ceremonies when Giorno’s teachers and friends travel from Asia. It is striking that, for a man who has lived for so long in one place, Giorno’s prolific, polymorphous productions are so centered on movement. Whether it’s his marathon poems full of insights and incidental reflections and mantra-like phrases that he regularly performs or his word paintings of fragmentary text (“JUST SAY NO TO FAMILY VALUES,” 2009; “A HURRICANE IN A DROP OF CUM,” 2009; “LIFE IS A KILLER,” 2009), his works refuse to stand still. They swirl and build and cultivate in their constant cultural rotation.

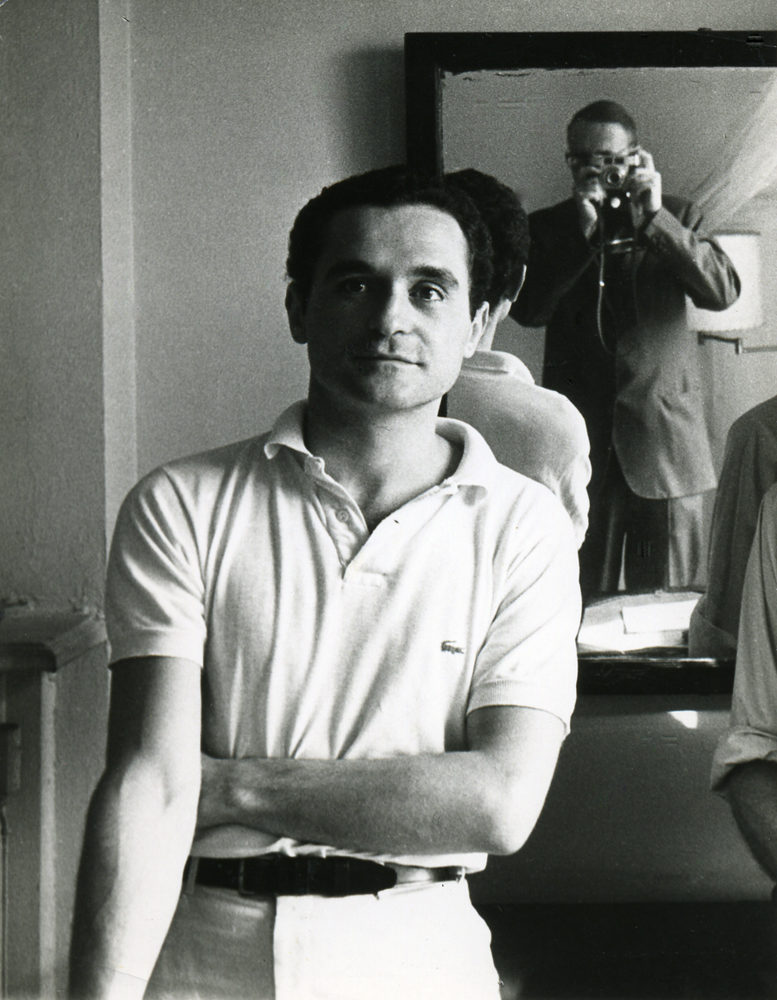

This is not surprising. At 76, Giorno hasn’t only been a New York resident for most of his life, he has also been a key artist and social lightning rod. He moved to the city from his childhood home in Long Island to attend Columbia University in the 1950s and eventually headed downtown. He became embroiled with Andy Warhol during his early experiments with film—Giorno is the star of the iconic black-and-white 1963 movie Sleep, in which he appears as a handsome, nude young man sleeping from various vantage points for the film’s entire five-hour run. Giorno was also friend (and sometimes lover) of artists Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, and it was these creative experimenters of post-abstraction and pop (unlike the New York School of poetry, with its absorption of abstract expressionism) that influenced Giorno’s poetic trials—a “found” style pulled from the streets, enacting the language and politics of the time but also a very revolutionary interest in the means of delivery for poems, using new technologies to bring art to the listener. So began Giorno Poetry Systems, a nonprofit foundation committed to opening unexplored channels. Giorno began developing sound pieces in 1965, through his introduction to William Burroughs and artist and experimental writer Brion Gysin. Giorno famously wrote a poem called “Subway,” and it was Gysin who encouraged him to record sounds in the subway, creating a composition out of the environmental audio, and instigating Giorno’s career in audio arts. In 1968, Giorno started his ongoing Dial-a-Poem series, where the public could dial a number and hear poems recorded by the likes of John Ashbery, Allen Ginsberg, and Jim Carroll (I personally like to think of it as a beautiful early version of the suicide-prevention hotline). Dial-a-Poem was exhibited in MoMA in 1970 and again last year.

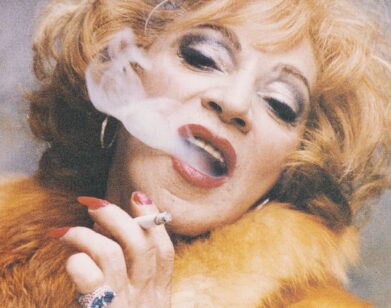

Giorno’s interest in the frontiers of technology continued through the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s as Giorno Poetry Systems released more than 50 albums of poetry and music, melding collaborators as diverse as Laurie Anderson, Gregory Corso, Patti Smith, Karen Finley, Hüsker Dü, Anne Waldman, Richard Hell, Philip Glass, and, of course, Burroughs (the catalogs for the records are like zines, with cartoons, short stories, and photographs). In the ’80s and ’90s, much of the money earned by Giorno Poetry Systems went to Giorno’s own community-minded AIDS Treatment Project. In 1998, Giorno met his partner, the Swiss multimedia artist Ugo Rondinone—who transitioned Giorno into another era of his career and into the folds of the current visual-art world. Rondinone is also a wordsmith, utilizing fragmentary texts in his series of rainbow light signs (one of which, Hell, Yes!, crowned New York’s New Museum, nearby on the Bowery, for three years). Rondinone is currently working on a black-and-white film of Giorno performing his 2006 poem “Thanks for Nothing.” The film will be shown as part of a giant retrospective devoted to Giorno’s art and life at Paris’s Palais de Tokyo in 2015. In the meantime, Giorno is exhibiting a number of his text paintings—including a show at New York’s Nicole Klagsbrun gallery in the fall.

Giorno may be one of the busiest, longest-running artists in New York, but in person, he is calm and kind, handsome and open, and it’s no wonder so many artists and writers have been drawn to him over the years. One artist, Rob Pruitt, stopped by the building on the Bowery in February, and the two spoke over Assam tea in Giorno’s painting room. On the wall was a painting that said this: “Eating the Sky.” —CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

ROB PRUITT: You resurrected your piece Dial-a-Poem last year at MoMA. How did that go?

JOHN GIORNO: It was a huge success. Dial-a-Poem happened at the Museum of Modern Art in 1970 at the “Information” show. Four phones were installed around the museum, and by dialing a number, you could hear one of 50 poets reading a poem. The idea actually started in 1968 and had a few incarnations before MoMA. I sort of stumbled on it by chance—this phenomenon of connecting a telephone with content and publicity. I was talking to someone on the telephone one morning, and it was so boring. I probably had a hangover and was probably crashing, and I got irritable and said to myself at that moment, “Why can’t this be a poem?” That’s how the idea came to me. And we got a quarter of a page in The New York Times with the telephone number you could dial. A million people called. And last year at MoMA, I reinvented it with new technology. In the old days, in its early incarnation, we had to have 12 telephone lines—with 12 poems by 12 poets every day.

PRUITT: So every day you would get someone new?

GIORNO: Yeah. When people were bored of John Ashbery, they would just hang up and wait for Jim Carroll or Allen Ginsberg or whoever. This was all before the internet, of course. But it was still people being bored at work alone. And all they wanted to do was reach out.

PRUITT: What do you think of Twitter? Do you tweet?

GIORNO: No, I don’t.

PRUITT: My studio assistants have set up an account for me, and they try to encourage me every day because they think it’s something that I might like. But it’s the same as swimming when I was young. It’s not something I’ve taken to naturally. In eight months I’ve written maybe seven tweets.

GIORNO: You mentioned swimming. Ugo [Rondinone] just got into swimming. He belongs to a pool practically right across the street on the Bowery. I said if we lived in a great castle of our own, the pool would be no further away than it is now. But in terms of Twitter, it’s not something for me either. I just don’t like doing that daily thing. I do love e-mails though. I love how minimal they are. But just because technology is simple doesn’t mean it needs to be part of our miraculous lives every day.

PRUITT: In the early years of Dial-a-Poem, using the phone in that way must have seemed like a new technology to some degree—or at least a very modern application of it.

GIORNO: I guess it was in a sense. Even a few years before, in ’66, Bob Rauschenberg started this thing called E.A.T., Experiments in Art and Technology, where he got great artists to try to work with engineers. They made some clunkers. There must be a lot of those artistic failures lying about somewhere. The funny thing about Dial-a-Poem was that there was no substance. It worked, but it wasn’t an object. In those years, artists were trying to make things, things, things… [Laughs]

PRUITT: But surely you must have had some poetic failures yourself—poems that just didn’t work. Do you save them? Or do you work on them until they do work?

GIORNO: I work on a poem until it’s finished, which is when I perform it. That’s when it’s fixed. And I perform it for a while if it’s good. I keep performing it. If it’s not, I let go of it, and I never bother with it again.

PRUITT: I’m dying to ask you about Warhol’s movie Sleep. When I was a young man, I felt that what that movie really was about, for me, was being able to see your naked ass! I wasn’t thinking about all the things film theorists have to say about Sleep. I was just thinking, Here’s this image of this beautiful ass. [Laughs] Did you feel exposed or did you feel part of it or did you feel more like a prop? How did you feel about being in that movie?

GIORNO: About the ass, I was just amazed that it got in the movie. That was a daring move for Andy. He was very aware of this. He knew in this homophobic world that he could not have a gay movie—that was the kiss of death. So I’m amazed that the ass got in there. I don’t know how it got in there. Andy was basically just thinking of the sleeping head or sleeping body. I stayed out of it, because I’m not a filmmaker, I’m a poet, and I know that it’s always best to leave the filmmaker alone and stay out of it. Andy had this Bolex. It was July of 1963, and he shot me for two and a half to three weeks, every other night or so. I drank a lot in those days. We’d go back to my apartment on East 74th Street at like one in the morning and I’d be drunk and take off my clothes. We were close friends. The problem was that there was a jerk every 20 seconds in the footage, because Andy would have to rewind it every 20 seconds. So when he developed it, none of what he initially shot was any good. Then right at the end, we met someone called Bud Wirtshafter, and he said, “Andy, there’s a gadget that you plug into the Bolex and into the wall, and it takes care of that jerk by spooling it out in two-minute rolls.” [Laughs] So then we filmed three or four more times over another 10 days, but the two-minute rolls didn’t work either. It took him a long time to figure the process out. He did thousands of rolls from September and October. He even hired people to create storyboards for Sleep but he still couldn’t figure out how to make it. It was depressing. But he was getting publicity for making the film, so he finally said, “Why do I have to do it? It’s already such a great success.”

“THINK ABOUT ALL OF THIS TECHNOLOGY NOW. MORE PEOPLE ARE PLAYING AROUND WITH WORDS IN THEIR OWN WAY. THAT’S POETRY, MORE THAN EVER BEFORE.” John Giorno

PRUITT: It’s known that you had a relationship with Andy Warhol. Was it just casual sex or did you feel like you two were boyfriends?

GIORNO: Andy was very difficult emotionally. We had this great love affair in a sense. But also not in a sense. Andy just liked occasionally giving blow jobs. Andy was peculiar. Occasionally he’d come over and give me a blow job for one reason or another, and that was the extent of it. But that doesn’t mean the passion didn’t go on—for the both of us. But Andy was just difficult. And it wasn’t such great blow jobs.

PRUITT: [Laughs] It can be a difficult thing to do.

GIORNO: Particularly when you don’t get much practice. [Laughs] I knew it was rare that he was doing this with anybody. I thought it was very special and I handled it as lovingly as I could. The interesting thing that nobody knows is that Andy Warhol had a beautiful body and a big dick.

PRUITT: Wow.

GIORNO: We slept together in the same bed when we were up in Connecticut in the summer of 1963. I remember he stood up from the bed, and I looked at him, and he had the most beautiful body of a young man. The classic body, perfectly formed, taut muscles… It was almost like a cliché—like Michelangelo’s David, that kind of young man’s body, with everything perfect. And he was hairless, so it was perfectly white alabaster. And then the Andy Warhol hair would stand out. [Laughs]

PRUITT: Like a bobblehead doll.

GIORNO: And Andy had a big dick! A Slovakian dick. This is true. I saw it hard and soft. I found a photograph of Andy taking a picture of his own dick. It was in a photo booth. Andy had a beautiful body and all those things that men like, but Andy Warhol’s mind saw his face and body as ugly, and so it negated his beauty. I think that’s curious.

PRUITT: Most people make the assumption that—

GIORNO: He was ugly all over.

PRUITT: Yeah, that his shyness was based on his ugliness instead of his insecurity. Anyway, speaking of Andy, I was thinking that the current short attention span of the population has caught up to the way that you’ve always thought of your poetry: quick and chopped and edited and fragmentary.

GIORNO: Finally, happily. It’s true.

PRUITT: There was a novelty item in the ’90s called magnetic poetry. People put it on their refrigerators. It was like magnetic tiles with words on them. Did anyone ever give you one of those sets for your birthday?

GIORNO: No, I never did that. I did those things myself, but maybe not as late as that. You can use any surface to write a poem. But even in the early ’60s, matchbooks were a place for poems.

PRUITT: How do you divide your practice between being a painter and a writer? Is it like one day you wake up and it’s your day to be a painter, and the next day you wake up and it’s your day to be a poet?

GIORNO: It’s all together. Technically I have two lofts in this building, one below the other, not including the bunker. I write upstairs. And I write for a number of hours until I take a break. The paintings are more complicated. The work is the same but it’s two very different things, in two different parts of the mind. I’m a poet; I write poems. So those poems are in my mind, and they go from the page or the computer to my performance of them, which is also a different act. Performing is a set of skills that you develop over the years. I’m not musically trained, I’m not trained as an actor, but somehow I do it. I’ve invented a way of performing. And then I have my silkscreen paintings. What I do with my words are paintings by hand, oil paint, or silkscreen. And that is a whole separate set of skills. It’s like another venue that requires some of the skills that a poet uses. And then the work can take other forms after that—into video and on and on.

PRUITT: Yeah, well, I’ve dabbled in different disciplines myself. [Giorno laughs] And the few times I’ve had to take the stage to even recite something that’s been scripted for me, it’s just so terrifying. I can approximate how it should be in rehearsals, but by the time I actually get up to do it, any qualities that may have been valuable for the audience are completely destroyed by the terror. Did you have to overcome terror in the beginning?

GIORNO: Yeah, it’s that way with everybody. The way you overcome it is just to do it all the time. As a poet, you just get invited to do this. Well, as a young poet you don’t get invited that often, but every week or two months, six weeks—finally the terror just falls away. I have absolutely no terror now. When you’re performing amongst a large audience, there’s an adrenaline that comes. Every performer has their own kind of chemistry, sort of like their metabolism. For me, I always get sleepy before a performance. Two hours before I’m going to go on stage, I take a nap. Something happens, like a doubt. It’s almost like I think, I don’t want to do this, but it’s not even in the front of my brain. My body just shuts down and I’m actually yawning. And then just before I go on, no matter how large an audience, I have to wake up and move the air around. It’s like the Olympics. In the spontaneity of the moment, your energy just comes. One example of a really great reading I recently gave was at a Hurricane Sandy benefit down in Santos Party House. I was a bit hungover from the night before, but I went in and read three poems. There were so many great people in the audience, and afterward everyone said, “John, you were so great,” but really I just did my usual thing.

PRUITT: Have you ever gotten booed?

GIORNO: Occasionally, in the ’70s and ’80s by the skinheads who’d be in the back of the club. There was one particular moment involving some skinheads right after the Laurie Anderson album [You’re the Guy I Want to Share My Money With, 1981] came out. William Burroughs, Laurie Anderson, and I were performing together, and the skinheads just didn’t like what we were doing. [Laughs] They booed. Another time I can remember distinctly was in Toulouse, France, at this sort of Louis XIV converted art center, in 1994. It was indoors and I was standing in the middle of the room and some skinheads started setting off fireworks at me.

PRUITT: Shit.

GIORNO: I didn’t miss a beat. Somehow they didn’t hit me. [Laughs] I finished and it was over. The title of my book that had just come out was You Got to Burn to Shine.

PRUITT: I love that title.

GIORNO: Afterwards, we were standing outside the center smoking joints. And across this little street I see the skinheads looking at me. I was startled and I went over—halfway over—and they came over to me and said, “We’re burning but we’re not shining.” [Pruitt laughs] I thought that was pretty great.

PRUITT: It is great. It’s like a real connection. What about poetry these days? Is it hard for you to see where poetry stands? Most of your adult life has been devoted to poetry. Can you evaluate its place in society? Do you ever think, “Oh, I wish I were doing something that people cared more about, like a crappy television show”? Obviously, words are still critical to culture, but poetry is seldom a best seller or at the front of a bookstore.

GIORNO: I have a different view. I just cannot do enough in my life. I perform endlessly. So what you’re saying about its lack of popularity is not a personal problem for me. But generally speaking, I think that the last 60 years have been a golden age of poetry that never existed before in the history of the world. So there. It’s really true. Before the ’50s, think of T.S. Eliot in the early ’20s, or Baudelaire and Rimbaud before him. They sold a hundred copies of a book. It was enormously powerful work, difficult and effective, but it took awhile to get out. Think about all of this technology now. More people are playing around with words in their own way. That’s poetry, more than ever before. Even tweeting and texting—texting is all about minimal words. It may seem mundane, but it is still the act of thinking about words. You seem to be saying that poetry is dead, Rob. Yes, a few traditions and forms have died—like the sonnet. But in general there is more poetry than ever. Rap is a poetic form. Most of it may be horrible, but a great rap performance is a great poetic form.

PRUITT: I may have been trying to say that poetry is dead, but what I was thinking about is a little more particular. I was thinking that it had no value as a commodity.

GIORNO: That’s something else. Poets never make money. It’s a phenomenon going back millennia. Poets are never paid in any culture. Just like they aren’t in ours. It’s not as though they aren’t famous. People like Allen Ginsberg—he was an enormously famous poet, right? But he made a very modest amount of money. He toured all the time and he got paid a thousand dollars a reading, so at the end of the year, he’d maybe make $200,000. But his peers in any other profession would be making $20 million.

PRUITT: Exactly.

GIORNO: And William S. Burroughs made even less, because he never toured and his books are difficult reading, so he didn’t sell a bunch of copies. So he was forced, on occasion every few years, to do something like a Nike commercial. At the end of his life, he did a Nike commercial and got, I think, a lousy $250,000.

PRUITT: Wait, Burroughs did a commercial?

GIORNO: A Nike sneaker commercial in 1994. He hit the jackpot—$250,000! But poets in every culture aren’t paid. Even the Chinese or the Tibetan Buddhists. If you’re a great lama, you get paid. But if you’re a poet, a crazy wisdom poet, you don’t. You end up with me, someone with a lot of fans. And that’s enough for me.

PRUITT: Why do you live in New York? It’s a fantastic city—young creative people make pilgrimages to New York. But you’ve lived in its epicenter, this one spot on the Bowery, for 50 years. It’s like stationing yourself 15 feet into the sea, where the waves never stop crashing. Do you ever think, Oh, I wish I had a peaceful country house?

“YOU JUST HAVE TO FIND WHICH ONE YOU’RE ATTRACTED TO IN ONE WAY OR ANOTHER. IT TOOK ME GOING TO INDIA TO FIND MY PATH, BUT EVERYONE HAS THEIR OWN PATH.” John Giorno

GIORNO: Oh, no. I have these three lofts on the Bowery: one upstairs; one downstairs; and then the bunker.

PRUITT: So this is your sanctuary.

GIORNO: Yes, and it’s very, very quiet. I live here and work here, and often I won’t see people for days because I’m working. I first stayed in this building in 1962 on the top floor. Andy was there many times in those years: ’62, ’63, ’64. There were many parties up there, [painter and filmmaker] Wynn Chamberlain lived there. And then I got the upstairs loft in ’66 and the bunker came with William Burroughs in ’75. I kept it after he left. And then Ugo Rondinone, my partner, and I have a country house in upstate New York.

PRUITT: Oh. So that takes care of that impulse. I just ask because I’m a little bit younger than you and—

GIORNO: I’m 76 years old.

PRUITT: And I’m going to be 50 in a year and a half. So I think that’s pretty close. Anyway, it bothers me to listen to people my own age lament that New York isn’t what it used to be. I really do love change and progress, even if progress really doesn’t seem like it’s signifying that something is getting better. How do you think about New York and the differences from decade to decade, from the ’60s until now?

GIORNO: I love New York, and because I was born here, I have this good fortune of New York never changing for me. I think now is as great a time as any. You know that world of Gavin Brown and the extended family of artists? That’s a great world, and all those other galleries—it’s a miraculous time. Going back through the decades, it’s never really changed. It looks different. It’s too expensive to live right on the Bowery or in SoHo, now they live in Bushwick. And, yes, it’s changed a lot in some neighborhoods. But it’s not worth complaining about. There are little differences. For instance, my birthday is December 4. So it’s December 4, 1963, Wynn Chamberlain gave a birthday party upstairs, on the top floor of this building. And that was when Sleep was released. At the party were Andy, and the seven pop artists with their boyfriends and girlfriends and wives, and then John Cage and Merce Cunningham were there, and Bob Rauschenberg came with Steve Paxton. Bob had just broken up with Jasper Johns two years before. Jasper came a half hour after Bob left with Steve. And then Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery—the New York School of poets, as they were called, five or 10 of those. And Jonas Mekas and countless others. There were 80 people. Frank Stella and Barbara Rose [art critic and Stella’s first wife]. That was the entire art world, from top to bottom, including Merce and John. There were about 20 people who didn’t come and it was only because they were out of town. It didn’t leave anybody out. There was nobody else in New York! And they didn’t come for my stupid birthday—they came to be together.

PRUITT: Because it was a party.

GIORNO: They knew it was this party, and they all wanted to be together. Nobody was really famous yet. Andy had just had his first show. It’s no different now in a sense. I mean, it was a great period, so it was all these great artists.

PRUITT: You’ve always been at the epicenter. You’ve always been fortunate to be where the action is.

GIORNO: By chance. I didn’t go looking for it. In 1965, I meet William Burroughs and Brion Gysin, and my work completely shifts. Burroughs was completely separate from the New York art world. There were parallels, but it was a different universe. And then Ugo and I have been together for 15 years now, so in that time the art world has again become very much a part of my life, because of him.

PRUITT: Did you start making the word paintings around the time you met Ugo, or did you make this kind of work before?

GIORNO: I’ve been doing this work since the ’60s. I did my first silkscreen work in 1968.

PRUITT: With the same font the whole time?

GIORNO: The same font since ’84. I’ve been fortunate to work with some really great designers, like Mark Michaelson, a designer of album covers and the art director of Newsweek. It was with him that I did the William Burroughs box set [The Best of William Burroughs from Giorno Poetry Systems, 1998]. Mark invented that typeface for me.

PRUITT: I wanted to ask you about Burroughs and the bunker downstairs where he lived. Do you know if he kept guns down there?

GIORNO: No, William never had guns in the bunker. He had a toy BB gun, which is legal, and we did target practice at hand-drawn circles taped to a telephone book.

PRUITT: I read something about you and Ugo recently that I thought was very loving—how you allow him into your studio when you’re making work and how he is very free with his advice.

GIORNO: Yes, he is. I’m very lucky. Actually, I’m too old for this! I’m a poet. But being with Ugo for the last 15 years, he’s been my art teacher. So when he comes here and I’m doing something wrong and I don’t get it, he’s very strong about telling me what he thinks. And it’s been great. When he gets really angry, I know I’ve done something really wrong. [Laughs] I’ve been doing watercolors recently, and I wasn’t sure why I liked doing them so much when we were traveling in Mexico. But Ugo said it’s because the air is so wet. That’s why artists in the South of France made watercolors. The air and the paper are filled with water. You know, I have a show coming up with Nicole Klagsbrun. It’s a bunch of new silkscreen paintings. I work on it every day. I have a book that I’ve been writing that’s nearly 620 pages, single-spaced. It’s nearly finished. I’ve been working on it since 1984. I pulled out some of the older pages to see, and one part was about being with Andy when JFK died.

PRUITT: Wow.

GIORNO: I wrote it 25 years ago, but I got asked to perform it at this show focused on memory [at the Serpentine Gallery in London]. But I don’t, for the most part, want anyone besides Ugo to read it until it’s done. If I should die tomorrow, it’s done. And there’s lots of sex, because I had a lot of lovers who I loved and I had a lot of sex with them!

PRUITT: That’s exciting.

GIORNO: I love writing about sex in the most happy, happy way. The publishing houses from the old days would never have published a book with gay sex. If it was heterosexual sex done with the correct hand, that would have been acceptable, but you still can’t publish gay sex at a major publishing house, because the book has to be able to be sold at Walmart or Kmart in Arkansas and Texas. This would have been a huge liability for me, but now, with books published online, my pornographic writing can be published successfully, I think. When the time comes… I’m happy for that miracle. Otherwise, I would have become an obscure little cult book that was undistributed.

PRUITT: So was Robert Rauschenberg a top or a bottom?

GIORNO: He was great sex.

PRUITT: I wish I had had sex with you so that I could be immortalized in your memoir. [Both laugh] Actually, I want to talk to you about meditation and how it has changed the way you write and make art. I’m asking this question because I suppose I’m a little bit envious that I let so many years of my life pass, and I don’t address these things that involve self-discipline. I only quit smoking six months ago.

GIORNO: Well, congratulations. That’s a really big thing. That’s important.

PRUITT: I knew that I needed to do that for the past 10 years, but I’m very slow to give myself the good things that I think would really change my life in a positive way. And I think that meditation falls into that category. How did you come to it, and how does it change your practice?

GIORNO: I’m a Tibetan Buddhist in the Red Hat Nyingma tradition, and I have been for going on 50 years. Buddhism is about training your mind. I learned about Zen and all of that when I was studying philosophy in school in the ’50s, but it wasn’t until I took my first LSD trip in 1964 or ’65 that I got the picture. When you’ve had a good LSD trip, it’s great, right?

PRUITT: Right. LSD fucking rules.

GIORNO: But when you’ve had a bad LSD trip, it isn’t the acid that did it—it’s your mind. That’s what propelled me. By 1965, Tibetan Buddhism had come to northern India. No one here knew quite what it was. I started meeting people in 1970 or 1971, and I went to India just to do it. It was doing something radical to change my mind. I had the good fortune of meeting my teacher, Dudjom Rinpoche, and a generation of these great lamas. I did endless practice over there, and I’d come back and do meditation practice here. I did many long retreats over there—go over there for six months and do retreats in Darjeeling and other places. I made a lot of progress in those years. And then Tibetan Buddhism came to America, and now it’s very easy; you just have to find which one you’re attracted to in one way or another. It took me going to India to find my path, but everyone has their own path.

PRUITT: When you chose to make that change in your life, was it for some reason, like, “Oh, I wish I didn’t sleep half the day away, and I wish I had a stronger work ethic, and I wish that I was kinder to people, and I really think I need to be more receptive…”

GIORNO: None of the above mentioned… [Laughs] It was only that I was suffering so much. I was so unhappy. I didn’t realize I had a depression problem, but I had one, and I still have one. The depression made me see that it was the nature of my mind that was causing the problem.

PRUITT: I have a depression problem.

GIORNO: I’ve always refused to take drugs, even now, these drugs that people take for whatever. I’m of the generation that when they gave you Thorazine and lithium, it killed you. You’d take it and be brain-dead. So I’m skeptical even of these nicer, lighter drugs they have now. And I’m really happy and healthy at the moment, and I like the work I’m doing and wouldn’t want to change that. The other side effect of meditation is that it really is training the mind. I think it’s had an enormously positive effect on my poetry, and all the things I do. For example, there is one meditation practice called tummo, a generation of heat—in images of tummo, it’s like a yogi sitting in the snow sweating. In tummo, you work with your breath and different parts of the chest and abdomen, moving the air around. And when you’re a performer, you do this all the time. I’d been doing this for years, not knowing what I’m doing. So I used this meditation as a way to help with my performances.

PRUITT: Do you meditate every day?

GIORNO: Yes.

PRUITT: Do you write every day?

GIORNO: Yes.

PRUITT: What do you do to goof off and waste time?

GIORNO: I like to smoke grass. That’s very helpful when I write. Grass is a very helpful writer’s drug. I smoke and work endlessly on one project to another. And the day passes. And I spend a lot of time with Ugo. We are lovers!

PRUITT: I can relate to that. I spend lots of time with Jonathan [Horowitz]. Getting back to poetry in culture: Do you think, when you look back on the history of poetry from the 1950s onward, that in a sense poetry was sidelined by rock-‘n’-roll? Like children were suddenly given a guitar on their 15th birthday and they redirected that emotion and interest into music rather than to poems?

GIORNO: Yes. And that’s just what happens. There were countless rock musicians who were poets when they were 12, like Patti Smith or maybe Tom Waits. Maybe they realized that was their route. I’ve always stuck with mine. In New York in 1960 or ’61, I started meeting people just being downtown, and they turned out to be artists. Not just Andy, but Frank Stella and Barbara Rose… And at the same time, I also know all the poets: Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery. You know, Frank hated Andy Warhol. He could be incredibly cruel to me because of my connection to him. They were only interested in you if you wrote exactly like the New York School of poets; otherwise you were sort of off their list. I was gay, so they liked me. And then there was Allen Ginsberg, who was an enormous influence on me from his poem “Howl” from 1956, when I first read it. Allen was a friend during this time. But I didn’t write like him, so I was off his radar. He liked me maybe because of Sleep, because I was famous for that. But what I mean by all this is that the poets around me really weren’t any help. They were a negative. But Andy and Bob Rauschenberg and Jasper—they were my main influence, seeing their openness of mind, seeing whatever idea came into their minds and how they worked with it. If it was a bad idea, they got rid of it, and if it was a good idea, they went on with it. It’s the poets that got stuck.

PRUITT: Do you listen to hip-hop?

GIORNO: Yeah, that’s all poetry. And, like everything else, a lot of it is bad. That’s why poetry is so great—there’s so much bad poetry around.

PRUITT: Yeah, I love bad stuff. [Laughs] Because it really allows you to see the moment you are living in. I have less interest in separating out the good from the bad. I just sort of like to be immersed in all of that as it’s happening. Speaking of immersion, tell me about Subway Sound [1965], which is the recording of ambient sounds in the subway. How did that project get started?

GIORNO: I met William Burroughs and Brion Gysin in January of ’65. They came, from among other places, Paris, and in Paris there was poésie sonore, sound poetry. It was an art form that people like Bernard Heidseick, Henri Chopin, and Brion were doing there in ’59, the early ’60s. Brion showed me what he had done, which is a poetry of sounds and words, using a bit of early electronics to make sound compositions. So I wrote this poem called “Subway.” And Brion says to me, “John, we should collaborate on a sound composition.” I was a kid, I had no idea what he was talking about. But we went into the subways and recorded sounds and made a sound piece out of my poem. Then Brion said, “Send it to Paris, to Bernard Heidseick,” who was doing a Bienal Biennale at the Musée d’Art Moderne. I did, and it was accepted. That set me off on a trajectory. I spent 15 years doing these sound pieces that scarcely anybody has taken note of, all the albums that I put out.

PRUITT: I’ve heard you talk about how a poem can get dated and how a work of art or great poetry is often defined by you as a mirror of a moment.

GIORNO: That’s very true. I think about it all the time because I perform all the time. And people are getting profoundly moved. I mean, you’re saying these words, and you see inside their minds. I’m not telling them anything; I’m giving out energy, and I’m holding up a mirror to their minds. It’s not me they’re looking at—it’s into their own minds. That’s what a great poem is. There’s no such thing as a great poet; this is only the poem. I mean, Andy’s Gold Marilyn [Monroe] is a great poem. Any great work of art holds a mirror to its audience. An example, for me, was “Howl.” When I read it in ’56, it had an enormous experience. I was a student at Columbia—a gay man, a poet—and what was a gay man then? W.H. Auden.

PRUITT: Or Montgomery Clift.

GIORNO: Or [Jean] Genet, but I’m not a criminal in Paris. I’m a gay man in America. So suddenly there is Allen Ginsberg holding up the mirror to me and a million others. And that was a seminal moment that changed the world. Now if you read “Howl,” it’s a really nice poem, but it doesn’t change anything because its job is done already. So that’s what my theory about poems and art is.

PRUITT: How did you start working on your first found poem?

GIORNO: I wrote my first found poem in the fall of ’62. In school I studied Duchamp and Dada and the Italian Futurists, but none of it had any influence on me. So it was really the work of Andy, and Bob Rauschenberg and Jasper, that got me on it. If they can do it for painting, why can’t I do it for poetry? It was interesting to watch how their minds worked—why they chose what they did and how it became a work.

PRUITT: Did you watch Rauschenberg and Johns make work?

GIORNO: I loved the way Jasper was so careful, the way he went from one thing to another. It was the opposite of the way Rauschenberg would do it. It was fascinating to see how the mind worked because you saw some kind of judgment that was being made.

PRUITT: Do you think about aging? Is the idea profound for you—getting older?

GIORNO: Oh no. I’m going to die really soon because I’m 76, and when you get to be 76…

PRUITT: I had a friend a couple years ago—Jonathan and I moved in next door to her. Her name was Erma, and she was 93. That’s many more years older than you.

GIORNO: You never know when you go. I’m more interested that my work is continuing. For the last decade or so, I’m really happy with the work I’ve been doing. I’ve been performing so much, and I know at some point the energy isn’t going to be there, and whenever that happens I will retire.

PRUITT: I sat down with a curator recently who wants to do a little retrospective of my work. She took 20 years of images and selected what she thought best represented my career and sent them to me. When I looked at them, I thought, “I’m such an awful artist.” [Giorno laughs] “I’ve been deluding myself all of these years.” Do you ever have feelings of insecurity like that?

GIORNO: Well, no, but I tend not to edit myself. It’s not right to be your editor. I have a big show coming up in 2015 at the Palais de Tokyo, and one floor Ugo is going to curate, which is why he’s doing a film of me.

PRUITT: Ugo is selecting your work?

GIORNO: I’ve collected a lifetime of photos and never thought about doing anything with them. So starting now, we’re scanning every photo of me, which is like 5,000 photos from 1962 on. And then we’re scanning my archive, every poem I wrote on the cover of a magazine or a book. And the curator wants everything, like that piece I did with Rirkrit [Tiravanija] in 2008 [JG Reads]. But in the end, I know well enough to stay out of it and let the curators do what they need to. It’s like with Andy and Sleep—I know enough to stay out of it and let them figure it out.

Rob Pruitt is a New York-based visual artist. He is represented by Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.