Jeffery Deaver’s Unbreakable Bond

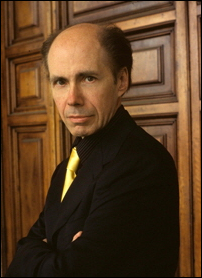

JEFFERY DEAVER. PHOTO COURTESY OF JERRY BAUER

James Bond is an icon—many things to many people, but still a man shrouded in mystery. In Jeffrey Deaver’s latest installment to Ian Fleming’s spy saga, Carte Blanche (Simon & Schuster), Deaver digs deeper into what drives the debonair 007. He was hand-picked for the job by the Ian Fleming Estate after winning an award bequeathed by them for his novel Garden of Beasts. Corinne Turner, Managing Director of Ian Fleming Publications, said, “I thought no way would Jeff be interested, and then his acceptance speech was all about how he loved Ian.” Deaver went on to deliver a sophisticated and stylish espionage thriller that takes us past the explosions, gadgetry and seduction to some deeper human truths, exploring Bond’s childhood and psychology. There are still creepy off-the-wall evildoers, bombshell babes, and plenty of death-defying dynamite action and drinking, but the Bond of Carte Blanche is more grounded, and more engaging. We caught up with Deaver in Amsterdam to discuss bringing a new outlook to an old spy, how mystery has changed since Fleming, bourbon vs. martinis, and the multiple meanings behind Pussy Galore.

ROYAL YOUNG: Ian Fleming’s James Bond is an orphan, and I was wondering if you think a measure of tragedy is important in shaping a hero?

JEFFERY DEAVER: Fleming was very sparse about details of Bond’s childhood. Bond’s parents died in a climbing accident and he had been shunted to boarding school and lived for awhile with his aunt. So when they asked me to write the book, that was one of the first things I wanted to explore. Do I think early tragedy is necessary for heroism? No, I don’t, but I do believe that it helps inform this kind of character, and that it was a very telling motive for him to become who he was: self-sacrificing, very much a patriot who had really had a bit of a vacuum of a childhood. His motive now, without sounding corny, is to make sure the people in his care have someone watching their backs that he did not have.

YOUNG: I definitely agree. And which other traits of Ian Fleming’s Bond did you feel passionate about maintaining?

DEAVER: I remember the pleasure I got out of experiencing Bond at a young age, and I wanted to bring that character that I recalled to my book. Partly because I found an extremely complex character. He’s morally unambiguous when it comes to his mission, and his mission is to protect people. He performs that function with style, flair, with a sense of humor. He is also sophisticated. He likes his wines, he likes the nicest things in life, but he doesn’t like them for the sake of indulgence. He is a man who lives on the edge, he knows he will be dead by the age of 45, and he is not going to live a Spartan life without experiencing what he can. It’s existential, though there is a puritanical streak too.

YOUNG: Though I think the puritan aspect is so contrary to him basically having a ton of sex.

DEAVER: Well, I will make a comment about the misogynistic charges leveled at Fleming.

YOUNG: Yeah.

DEAVER: I refer readers to Mad Men. There’s an element of how life existed then, and the disparity between the genders at that time. Fleming, if I could level any criticism, some of the terminology, some of the packaging was a bit inappropriate. And yet, he created very empowered women – Rosa Klebb, for instance, in From Russia With Love, was a mastermind. Characters like Pussy Galore, of course there’s the name, but she was head of a gang. And I’ve actually heard the theory that the word pussy did not necessarily mean what we now think of it as meaning. It was a not uncommon endearment in the late 1950’s and early ‘60s, fathers would refer to their daughters that way, as either “kitty” or “pussy.” I do not have Bond girls in my book. I have Bond women. Bond only responds to powerful women.

YOUNG: The world has changed very much in terms of oversharing on the internet and just having access to so much information. How do you think that’s changed our relationship to spying and mystery?

DEAVER: I’ve been very aware of the power of the internet and you cannot write about espionage nowadays without taking that into account. In the 1950s there were microdots, which you may remember—I don’t know your age.

YOUNG: [laughs] I was born in the ’80s.

DEAVER: [laughs] Well, people were always looking for the microdot, or microfilm, but now of course it’s all digital. So Bond has an iQPhone, because it was created by Q Department. Technology has become so ubiquitous in our culture, you can’t neglect it. But beyond that I did want to get back to the human side of spying, feet on the ground, undercover. Military and all tactical operations are ultimately about people.

YOUNG: Well, removing the phone or the internet from the situation gives it more immediacy.

DEAVER: Yeah, exactly. While acknowledging the importance of technological intelligence – certainly we need to gather information that way—I found it was the human and interpersonal relationships that drive the story forward.

YOUNG: How does Bond reflect current ideas about masculine style? Because certainly part of his persona is a put-togetherness, knowing about good wines and having the best suits.

DEAVER: I think part of it is a quality I didn’t think of earlier. He’s very self-assured. He has very specific ideas and he happens to wear Canali suits, why? Because I happen to like Canali.

YOUNG: [laughs]

DEAVER: [laughs] Just for the record, Canali didn’t pay me anything.

YOUNG: Good to know.

DEAVER: And by the way, no Bentleys have showed up in my garage. I keep checking and there just aren’t any. I think in the movies, there’s product placement and payoffs. I got one fifth of whiskey, no champagne, and certainly no Bentleys. But Bond has very clear ideas of what he likes and what he doesn’t. I don’t know if I’d call that a masculine style, I think it’s a self-assurance that certainly crosses gender lines.

YOUNG: To what extent is Bond the man every man wishes he could be?

DEAVER: It doesn’t get any better than Bond, believe me. The reason for that, though, is not the trappings of Bond. You have to be a nonconformist, intolerant of mindless authority, you have to make your own way and do it with a passion. I’ve worked for law firms, I’ve worked for corporations, and for the past 20 years, I’ve been writing working for myself, and believe me it’s a lot better. That’s a big part of the Bond panache, that you’re responsible, 100 percent responsible, for the success or failure of your mission in life, whatever it is.

YOUNG: Why shaken instead of stirred?

DEAVER: Oh! There’s a real answer to that!

YOUNG: Is there?

DEAVER: Yes. Well, first of all Bond was a bourbon drinker, as am I, and still waiting, did I mention, for cases of bourbon to show up at my house. None have.

YOUNG: [laughs]

DEAVER: But the shaken, not stirred is when you shake a martini it aerates, it really works oxygen into the vodka and flavors the vodka. Fleming never described this, but I did some research on it—a very tough job, I had to sample a number of different types of liquors and mixed drinks in various ways. But really, given Bond’s proclivity for knowing what he likes, I think it makes perfect sense.

CARTE BLANCHE IS OUT IN THE US AND CANADA JUNE 14. FOR MORE ON JEFFERY DEAVER, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.