ask me anything

Gloria Steinem Takes Questions From 25 Formidable Friends and Fans

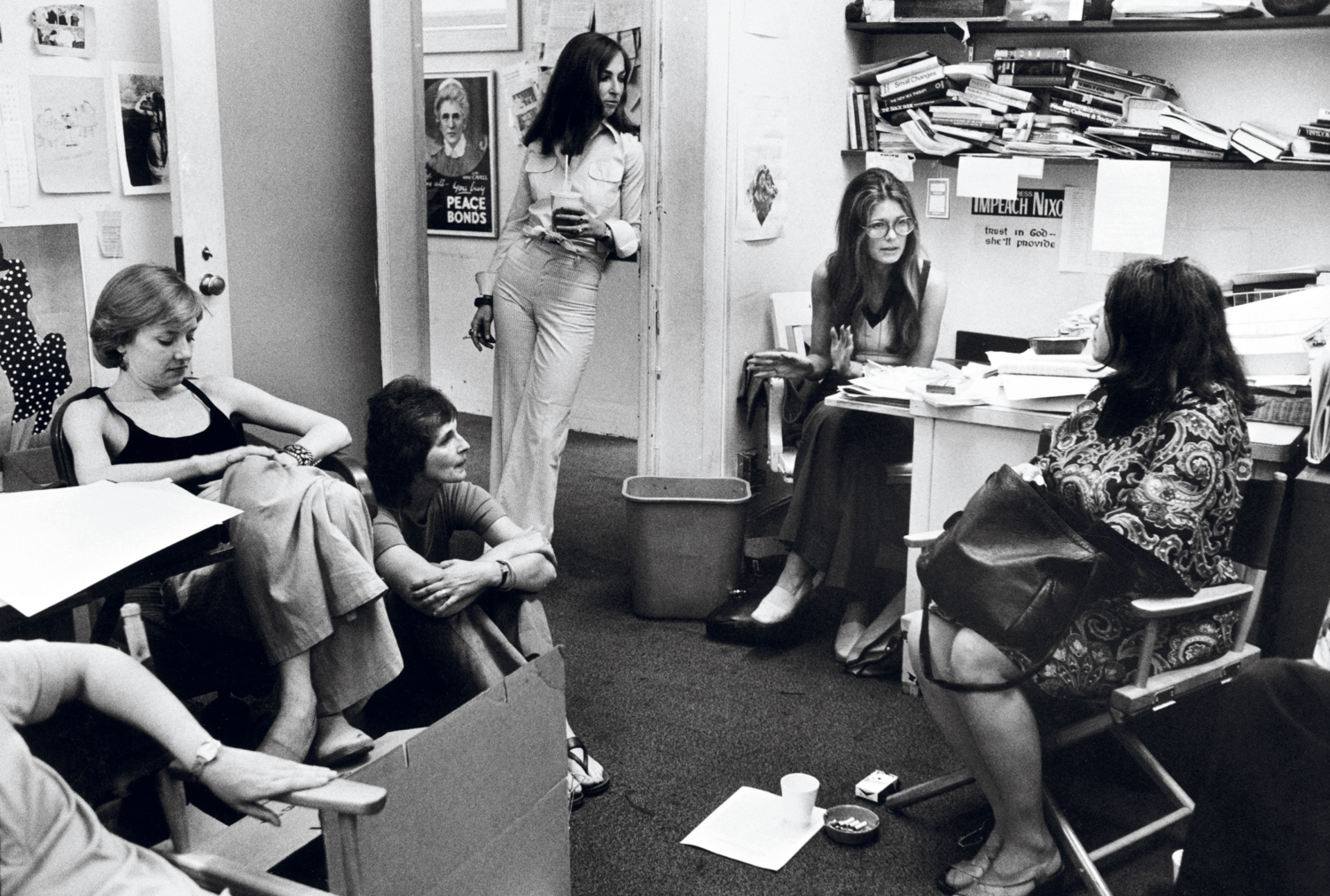

The last time Gloria Steinem appeared in this magazine, back in the summer of 2011, she told Maria Shriver, “Revolutions that last don’t happen from the top down. They happen from the bottom up.” Who could have predicted how timely, how resonant, those words would be today? Steinem, that’s who. As with all the wisdom she imparts, her passion and prescience are rooted in experience. At the age of 86, the Ohio native has seen it all: as a politically wide-eyed Smith College student immersed in the traditions and cultures of India; as a journalist battling misogyny in the newsroom and documenting it by going undercover as a Playboy Bunny; as a soldier in the battles against the war in Vietnam and the war on reproductive rights; as a co-founder of the pioneering feminist magazine Ms.; as an organizer of female-led Equal Rights Amendment marches; as a recipient of countless honors, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, for her service to humanity; and as a target of cultural fascination—and, for some, derision—since she first devoted her life to the cause of gender equality six decades ago.

This month, Steinem’s biography will be told on the big screen in The Glorias, a film co-written and directed by Julie Taymor, and based on Steinem’s 2015 bestselling book My Life on the Road. Played at various ages by four actors, including Oscar winners Alicia Vikander and Julianne Moore, Steinem is depicted in the movie as a tenacious disrupter whose life’s work has been about questioning the disparities upheld by authority. In the lead-up to its release, we reached out to 25 of Steinem’s formidable fans, friends, and co-conspirators, all of whom had some questions of their own.

———

GAYLE KING: I recently watched The Glorias, and there it was, one of my favorite Gloria Steinem quotes: “The truth will set you free, but first it will piss you off.” What truth has pissed you off the most in your life?

GLORIA STEINEM: Just unfairness and unkindness, and all the situations in which we see those two things, knowing that it does not have to be that way. I suppose that both result from a lack of empathy. People who cannot feel—there’s one in the White House—are the most dangerous.

———

JULIANNE MOORE: I am so impressed and inspired by your patience and tolerance, and how thoughtfully you have instigated change. Which female leader have you found most inspiring, and why?

STEINEM: The problem is that most people won’t know the female leaders I tend to find inspiring. I’m thinking, for instance, of Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay from India. She was a great leader of the independence movement and of the women’s movement, and just incredibly foresighted. But there are different ways of leading. I think of Alice Walker, because she is so true in her writing that she helps everyone who reads her—or knows her, or knows anything about her—be true to themselves.

———

ALICE WALKER: If you were not Gloria Steinem, who would you like to be?

STEINEM: If I were not me, I guess I would like to be a woman who only learns about patriarchy and racism and monotheism and nationalism from history books. I would like to be a woman for whom those things have all long, long, long passed. But I would still imagine myself as a woman. I can imagine myself as coming from India or Africa, but I can’t quite imagine myself as a male person.

———

DIANE VON FURSTENBERG: If you had to be a man in history, who would it be?

STEINEM: I find it very hard to imagine being a man, but ever since I lived in India in my twenties, I’ve been fascinated with Ashoka, a ruler there in the 3rd century BC. He democratized legal knowledge by carving laws into stone pillars around the country, treated all life as sacred, including animal life, and seemed to be doing the best he could to change the patriarchy he was born into.

———

JULIE TAYMOR: Of all the women you have worked and marched with, who made the greatest difference in your life?

STEINEM: [The late Cherokee activist and community developer] Wilma Mankiller. I learned from her that so much of what we hope to gain was once ours. Before I met Wilma, I thought that what we wanted in the future had either never existed, or could never exist, but only from knowing Wilma did I discover that most of it, once, was here.

———

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Out of all the photographs I have taken of you, the one with you and Wilma Mankiller still seems to be the most important to you. When you look at this photograph now, what do you think about?

STEINEM: How much I miss Wilma. She was younger than I. She should be with us still. I miss her every day.

———

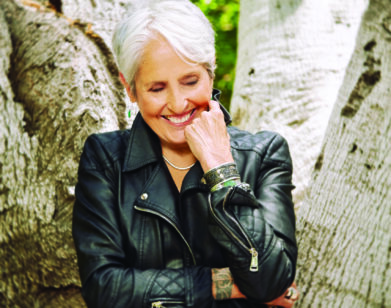

MAXINE HONG KINGSTON: You and I first met on a spring day in March, the month of your birthday and my husband Earll’s birthday. You gave him a gift. “Here’s my birthday present to you,” you said. “This is what 40 looks like.” Earll is now 82 and I am 79, turning 80 in the fall. My question to you is: Tell me, Gloria, what does 86 look like?

STEINEM: I’m doing my best to understand that I’m not immortal, even though, of course, we continue to think we are. But I’m working hard on my sense of mortality because I feel like it will help me to use my time better, to do what I truly care about. Writers are always putting off writing, and I’m very good at that, especially because I’m also an organizer, and there are infinite possibilities to think of as hopeful or angering, or which have potential for organizing. It’s very distracting. I’m not sure if this is true of all writers or not, but it probably is: Because writing matters to me so much, I tend to put it off, yet when I’m doing it, I know it’s the one thing in the world I should be doing.

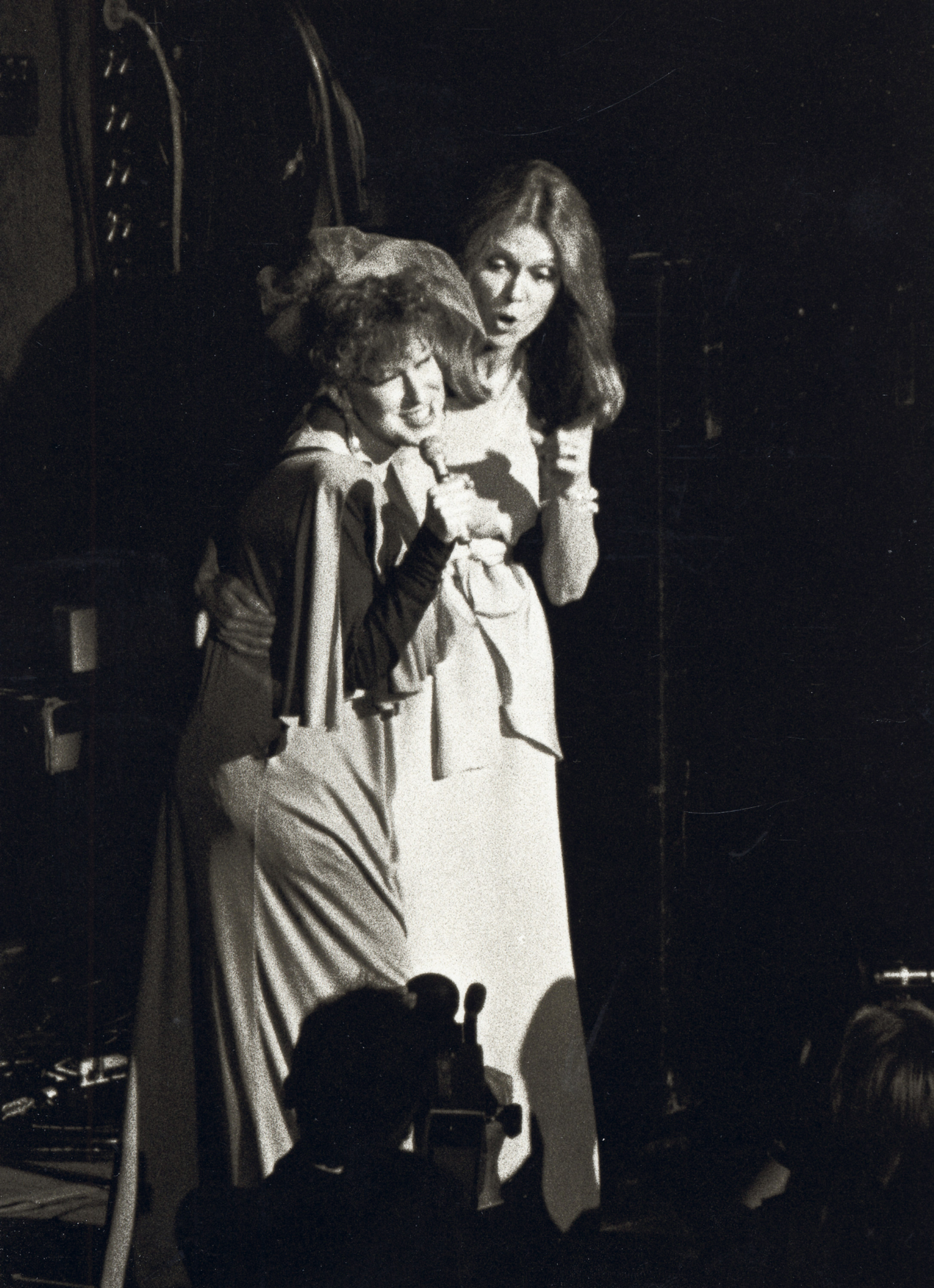

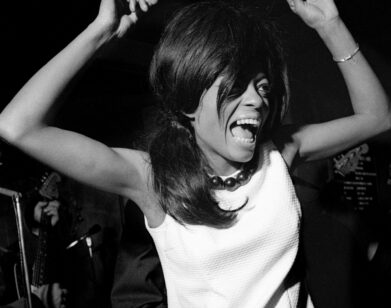

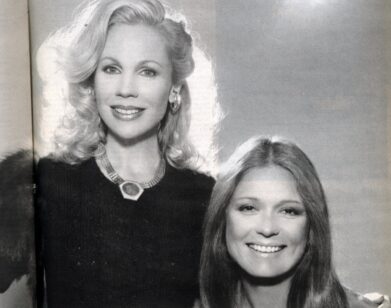

This spread, clockwise from top right: Adam Scull, MediaPunch Inc./Alamy Stock Photo; Ron Galella Collection, Getty Images; Copyright Annie Leibovitz.

AMANDLA STENBERG: How does your practice transmute as the language of gender expands?

STEINEM: Oh, language can easily go beyond gender. We just have to rethink and abandon labels. We can refer to somebody by their name without saying, or having to say, where they come from, or what gender or race they are, but by the fact that they are a unique human being named Dorothy or Vladimir. I also think that COVID-19 has helped us go beyond adjectives, because the pandemic doesn’t recognize, and is not limited by, race or class or gender or nationality. I think it’s helping us realize that we are all human.

———

MELINDA GATES: When progress toward gender equality feels too slow, what keeps you hopeful?

STEINEM: Age is helpful. I remember when it was so much worse. One of the functions of us older people is hope, because we remember when it was worse, and one of the important functions of younger people is anger, because it should be so much better. It’s why we need to organize together. Age segregation is as wrong as any other form of segregation.

———

ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON: As a Member of Congress, I would appreciate your advice on which of many issues Congress should flag for attention next year because of its importance or because the issue is most achievable in the short run.

STEINEM: First, I trust you to know the answer to this question better than I do. You are way more knowledgeable about the art of the possible, especially in Congress. If we look at the most basic issue, in the sense that it is the first step in hierarchy, it is controlling women’s bodies as the means of reproduction, which is redoubled if there is racism, because then there’s far more motive to decide what groups increase and what groups don’t. The first step in every hierarchy I’ve ever witnessed or read about is patriarchy. It is about controlling women’s bodies, since we happen to have one thing that men do not: wombs. So I would say that the first step toward true democracy is for everyone, men and women, to have decision-making power over our own bodies. If we focus on that, all else will follow.

———

BETTE MIDLER: Which book galvanized your thinking, and what is your favorite book?

STEINEM: There are so many. My favorite book, as a child, was Little Women. It was the first time I realized women could be taken seriously on their own, and could form a whole society. Now, there is a Ghanaian author named Ayi Kwei Armah. His is the only writing I’ve read that bridges pre-patriarchal and precolonial times to the present. He makes you see both past and future possibilities.

———

JANE FONDA: You once told me that you wanted to live to be 100 years old because you wanted to “see how things turn out.” What do you think you would be most interested in 14 years from now?

STEINEM: I was much younger when I said that. Now that I’m close to it, it’s harder. There’s a Native American story that says that if human beings become too destructive to Earth, itself a living thing, then Earth will shrug us off and start over. I think about this often, and wonder if COVID-19 is Earth beginning to shrug us off. I would like to know the answer to that question.

———

STACEY ABRAMS: How is the right to vote integral to the continued advancement of women’s rights?

STEINEM: The voting booth is the single place on earth where everyone is equal. If we don’t have full access to that, we can never be equal. And how we vote is our most important voice, so voting is fundamental to women’s equality and safety and humanity.

———

CHELSEA HANDLER: Who or what has been the greatest love of your life?

STEINEM: Possibilities. I fall in love with possibilities. I see a problem and I’ll think, “Well, if we could just get these groups together they could solve it,” or, “If I could introduce this person to that person, or raise money for this project…”

———

JOY REID: With the Equal Rights Amendment so close to having enough states ratify it, but with women having made so many advances since the days when you launched Ms. magazine, what, in your view, would materially change for women if the ERA became a constitutional amendment?

STEINEM: Everything. To be present in the Constitution would make an enormous difference. So much would change if sex discrimination rose to that level. Also, we would join every other democracy in the world that includes women in its Constitution.

———

REID: When I was in college in the 1990s, Black and white feminism faced a significant culture clash. Women of color and white feminists were rarely rowing in the same direction, and there’s a history of that, going all the way back to the fight for the 19th Amendment [which guarantees American women the right to vote]. In your view, how can we use this moment, with the Black Lives Matter movement—which has become preeminent despite the continued prevalence of “Karening”—to create a unified, cross-racial feminism?

STEINEM: First of all, Karen is not a feminist. That woman we all saw in the park clearly was not a feminist. Feminism either includes all women or it’s not feminism, and one thing that would be helpful is if our history were more accurate, because Black women have been way more likely to be feminists than white women, just statistically speaking, from the very first public opinion poll that was done in 1972. Black women have been about twice as likely to support the causes of female equality as white women, largely because a fairly big number of white women are still dependent on the economic and social standing of their white husbands. So instead of voting for their own self-interests, they’re voting for their husbands’ interests.

REID: Who is your heir apparent?

STEINEM: I do not have an heir apparent because I am not a leader. I’m just part of a movement, so my heirs apparent are a multitude, and I learn by listening to all of them.

———

MONA ELTAHAWY: As a woman who is childfree by choice, I know the taboo of saying out loud the freedoms that have come from such a choice. How has choosing to be childfree impacted your life?

STEINEM: I would put the emphasis on“free.” It has increased my freedom. Everyone has a right to make this choice, or hopefully has the ability to make the choice to be a parent or not. It was always clear to me that I did not want to be a parent, so, although I, of course, understand and see the joys and rewards of parenthood, I experience the freedom that comes without that responsibility and connection.

———

BROOKE SHIELDS: As a journalist and the editor of Ms. magazine, is there one interview you wish you could redo?

STEINEM: For Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was then the head of the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project, I went with her colleague, Brenda Feigen Fasteau, to interview Fannie Lou Hamer, the great civil rights organizer, in Mississippi. She had been sterilized in a hospital there without her knowledge or permission, after she entered for a different procedure entirely. For Ruth and Brenda, her interview was very valuable in fighting off state laws that tried to enforce the sterilization of Black women on welfare, but also to restrict the voluntary sterilization of white women unless they had several children and their husband’s written permission. What could be more racist than that? Fannie Lou Hamer’s interview helped Ruth and Brenda protect the reproductive rights of Black women and girls who were subject to racist laws in state legislatures, but I’ve always regretted not asking Fannie Lou if I could also publish her words in Ms. magazine. A lot more people would have learned that patriarchy controls women’s wombs—which is why abortion remains supported by most Americans but opposed by patriarchal religions and racists—and racism doubles the motive for controlling all women’s bodies. Wherever there is racism, women of color are in the most danger, but white women are endangered, too.

———

MAXINE WATERS: We have known each other and worked together since the 1977 National Women’s Conference. You asked me to serve on the board of the Ms. Foundation for Women, which was one of the most wonderful experiences of my career. We’ve talked about a lot of things over the years, but I have never asked you about your experience as an undercover Bunny at the Playboy Club. What was that experience like? Did you meet and talk with Hugh Hefner? What did you say to him? What did he say to you?

STEINEM: Being a Playboy Bunny was like being hung on a meat hook. I had to work very hard in 3-inch heels and a costume so tight that I could hardly breathe. I did not meet Hugh Hefner during the dreadful experience of being a Playboy Bunny, but I did meet him when I interviewed him. The most surprising thing about him was that he was pathetic. He was like an 8-year-old boy pretending to be a grown-up man.

———

JANELLE MONÁE: What did you think about vibrators when they first came to mass market and became visible in mainstream culture? If you have ever used one, which do you recommend?

STEINEM: My dear Janelle, I don’t mean to be disappointing, but my generation discovered vibrators for reasons other than orgasmic. We thought they were about having muscle aches and pains. They hadn’t yet become erotic.

———

AMY SCHUMER: Is there a fun sexual experience you would be down to share?

STEINEM: Anything that starts with mutual massage is a good thing.

———

ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ: How have you seen the role of intersectionality in feminism evolve over the years? It seems as though in this moment, many people are revisiting the work of feminists like yourself, Angela Davis, Dolores Huerta, and the Combahee River Collective. How does this moment compare to the beginning of your career?

STEINEM: I agree that we’re rediscovering the beginnings of this wave of feminism, and they were always intersectional. I learned feminism mostly from Black women. I learned organizing from Dolores Huerta. Of course there are divisions in the movement, but the problem is less the divisions than the blindness and inadequacy of history. There was an assumption on the part of journalists—and newspapers are the first draft of history—that the Women’s Movement was white, and the Civil Rights movement was male, and therefore women of color, Black women especially, were not well recorded in either.

———

DOLORES HUERTA: With all the opportunities of lucrative careers, why and when did you decide to focus on the most difficult women’s issues?

STEINEM: Well, they made everything else boring. Also, I was not thinking in terms of a career, because I’ve never actually had a job. I’ve always been a freelance writer or editor. I’ve never had a nine-to-five.

———

SHARON STONE: How have you dealt with the straight male need to control you by not only diminishing your accomplishments but by intentionally choosing to not respond to your emotional needs because they were threatened by your independence?

STEINEM: I left. I left and found another man.

———

HARRY BELAFONTE: I’m wondering, DO YOU STILL LOVE ME?

STEINEM: Completely. I completely love and admire you.

———

MICHAEL MOORE: You grew up in working-class Toledo (a city which we in Michigan like to call “the Flint of Ohio”). But your parents brought you to Michigan each summer, and I’m curious what your memories are of Michigan. Also, are we gonna make it?

STEINEM: My memories of Michigan are of Clarklake, which is actually all one word, oddly. Clarklake. I remember a small freshwater lake full of minnows and turtles and springs and sandy beaches and clear water and many delights. Michigan, in my life, was about nature. And yeah, we’re going to make it because there are people like you.