Edmund White

THAT’S WHAT YOU DO—YOU BECOME THE FLANEUR. I NEVER HAD SO MUCH FREE TIME IN MY LIFE AS I DID WHEN I LIVED IN PARIS. EDMUND WHITE

Everyone says he or she wants to live in Paris, but the reality is somewhat daunting—a strange language spoken rapidly, a culture that rivals and a history that far surpasses America’s, winters during which it rains every single day, an exorbitantly expensive town. No wonder so few Americans go there for long, just long enough for their fantasies to wear off and the cold, wet reality to dawn on them like a bad hangover.” Strangely, this gorgeous observation remains untrue for the man who wrote it. For novelist and essayist Edmund White, Paris was, for a while, his place.

White’s latest memoir, Inside a Pearl, out this month from Bloomsbury, covers his days and nights following his move to Paris in 1983, partly on a Guggenheim fellowship, partly as a correspondent for Vogue, partly, in his own words, for “a new lease on promiscuity” when the AIDS crisis had reached its devastating height in New York, and partly, one suspects, to convene with the ghosts of literary gods like Proust and Genet and find the Xanadu of European high culture. White stayed for 15 years. Any reader who feasted upon and squealed at the scruffy, sexual street orgy of his last memoir, 2009’s City Boy, which encapsulated 1970s New York, may be surprised by the refined, blue-blooded café society charted so meticulously in Inside a Pearl. But the 74-year-old White proves once again, like a scopophiliac in a hall of mirrors, that he is the unrivaled master of nailing down a time, a place, a mood, and its walking, talking, erring, outrageous denizens.

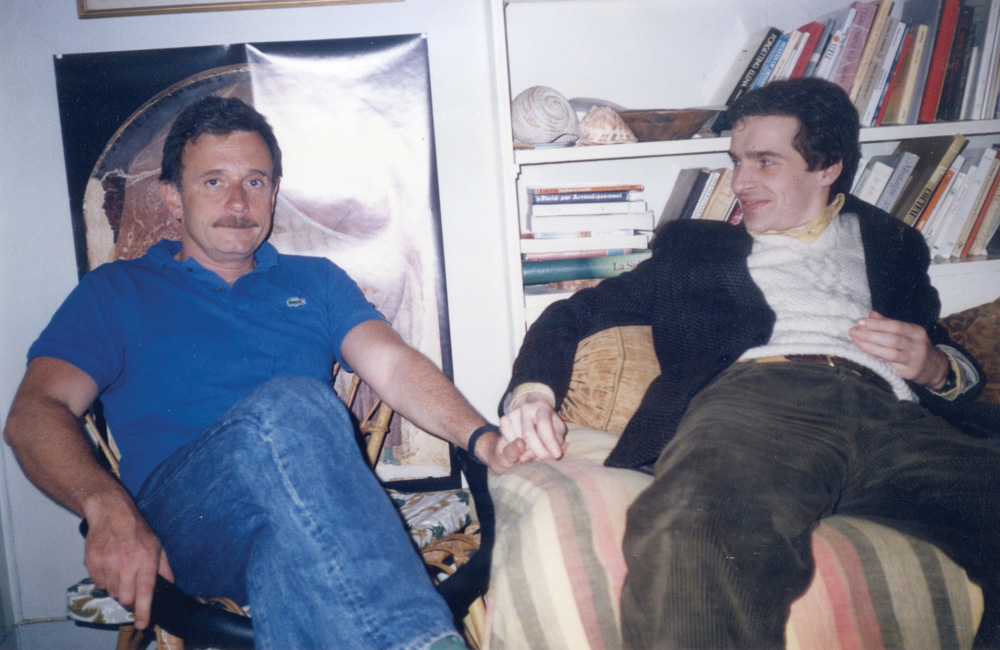

White’s grand banquet comes with a delicious roster of cameos—Michel Foucault, Ned Rorem, Milan Kundera, Mary McCarthy, Lauren Bacall, Julian Barnes, Nigella Lawson, Dominique Nabokov, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Azzedine Alaïa, Paloma Picasso (it seems likely that if any of the jet set attended a dinner in Paris in the ’80s or ’90s, they might have shared a bread plate with him). But Inside a Pearl is also a dedication to the lovers and companions and night-time cruisers who get equal footing in the sweeping, Bank-to-Bank narrative—the young, drifting American John Purcell who accompanied White to France, a Swiss cinema manager named This with an impressive art collection, and his current partner, writer Michael Carroll. Early along the way, White tests positive for AIDS, and a trace of flinching mortality underlies the extravagance and dizzying spree that makes Inside a Pearl such an exhilarating ride.

White has set to page the ins and outs of Paris before—particularly in his literary walking guide, The Flâneur, in 2001. But he’s never written about the city with such an expert mix of anthropology and vulnerability. “People in Europe liked to talk about American ‘puritanism,’ by which they meant not only prudishness, but also distaste for luxury,” he writes. “The French liked clothes and interior decoration for their own sake, not as status symbols alone but also for the comfort and pleasure of contact with fine things.” “The comfort and pleasure of contact with fine things”—an accurate assessment of reading White’s latest work, and puritanism is not a word that applies. In the following conversation, White spoke by phone from his apartment in Manhattan with writer Dennis Cooper, who currently resides in Paris: two literary expats sharing impressions of one city. —Christopher Bollen

EDMUND WHITE: I can’t believe you’re in Paris. How do you like it?

DENNIS COOPER: I actually really love it. I’ve been here, like, almost eight years—or over eight years now …

WHITE: Paris can be like the land of the Lotus-Eaters. You can’t leave.

COOPER: And I don’t even speak French well. [laughs] My comprehension is okay, but I don’t speak it. It’s strange, but I tend to get by okay.

WHITE: Well, you’re cute. When I was living in Paris in the ’80s, I used to go out with an American model who couldn’t speak French. But suddenly everyone could speak English because he was so cute. [laughs]

COOPER: I don’t know if that’s the reason, but I can speak in French and they tend to answer in English, so it works out somehow.

WHITE: I’m so curious if the Paris from my memoir sounds at all like your Paris?

COOPER: No, it didn’t at all. That was the interesting thing about it. I live in the 10th arrondissement, not the fourth like you did. But I think my life is so much quieter than yours was, in general. I mean, I have fun, I do … But I was very interested in how different our experiences have been.

WHITE: I was working for Vogue when I got to Paris, so my Paris was kind of snooty. I had convinced Vogue that I was fluent in French, although when I first moved here, I wasn’t at all.

COOPER: One of the things I loved most about the book was the fact that you interviewed Éric Rohmer in 1984.

WHITE: I did. And I couldn’t understand a word he said. [laughs]

COOPER: Another thing I liked is that your memoir got me reading Jean Giono again. I just picked up a book of his.

WHITE: I wrote a long article on Jean Giono for The New York Review of Books. I spent most of fall writing it. I went to his house in August when I was down in Provence and met his daughter, who is in her eighties and arrived on a motorcycle. A fair number of Giorno’s books were translated into English, but I think most of them are out of print.

COOPER: He seems like a super-interesting guy. Whenever I say the name, everyone thinks I’m saying John Giorno.

WHITE: Yes, when I mention him, people say, “Oh yeah, I read ‘Eating Human Meat.'” I like both writers, but they couldn’t be more different. So, what have you been doing in Paris?

COOPER: I’ve been doing a lot of collaborations. One of the reasons I came to Paris was to work with this French theater director and choreographer named Gisèle Vienne. We make theater works together, and I’ve been doing that since I’ve been here. They were only put on a little bit in the United States because there’s not the money to bring European avant-garde theater over anymore. And, of course, I work on my novels. Other than that, I just sort of wander around.

WHITE: Yeah, that’s what you do—you become the flâneur. I never had so much free time in my life as I did when I lived in Paris. In New York I never seem to have any free time.

COOPER: It sounds like it. You got to meet some incredibly interesting people. It was such a different time. Like being in Paris with Michel Foucault …

WHITE: I first met Foucault in New York. And then I saw him in Paris. I invited him to a gay bar. He said it was hard for him to go out in Paris because he was too famous, and I said, “Oh, come on.” But then, when we went to the Bar Hotel Central in the Marais, he was mobbed by fans and he ran out and jumped in a taxi. I was flabbergasted. When he died in 1984, he was on the front page of every newspaper.

COOPER: I feel like, in comparison to your Paris, I know fewer people. I know a few writers, like Marie Darrieussecq and Emmanuel Carrère …

WHITE: Emmanuel Carrère is among my favorite living French writers. And I like Jean Echenoz, too.

COOPER: You had some wonderful details about Pierre Guyotat, who, as you can imagine, I love.

WHEREAS MY YEARS IN NEW YORK HAD BEEN PRETTY GRUNGY, RUNNING AROUND HAVING SEX IN TRUCKS, IN PARIS I WAS ALWAYS IN A COAT AND TIE… Edmund White

WHITE: I met him through my translator. Pierre would give performances at a museum where he’d speak in his own language, in which every word sounded, to me, like testicules.

COOPER: He has such a huge head. I really admire him.

WHITE: I know. With his bald head, to me, he looks like the great god Baal.

COOPER: There’s a part in the memoir where you describe that Louis Malle wanted to buy the rights to your novel Caracole.

WHITE: Yes, I had lunch with him after he had read that baffling, tedious novel of mine and he wanted to buy the movie rights. “Why on earth?” I asked. He said, “Well, it’s a fantasy novel about a superior people being ruled by an inferior one, and as a child, I lived through the Nazi occupation of France.” Then he told me the story of how they harbored a Jewish boy at his Catholic boarding school, but one day he was betrayed to the Nazis and they hauled him off to the death camps. “That’s your movie!” I said, shooting myself in the foot, and he made Au Revoir Les Enfants, one of his best films.

COOPER: I know a few filmmakers in Paris. Like Christophe Honoré. I had coffee with him, like, two hours ago, actually.

WHITE: I never met him, but tell him I’m a huge fan. In his movie Les Chansons d’Amour, the way you know the cute boy, Erwann, is gay is that he’s reading The Beautiful Room Is Empty, one of my books.

COOPER: I actually was in one of his films. I have a small role in the one called Man at Bath, or Homme au Bain. It’s kind of like his sexy movie. [laughs] It has François Sagat in it, the big French porn star. I have a scene where I humiliate him. And he’s naked at the time, too, so that was cool.

WHITE: I thought Ma Mère was the sickest movie I ever saw, which is kind of a compliment. Did you ever see that one? When he’s beating off next to his mother’s corpse … That was a bit much for us poor little Americans.

COOPER: That’s his big moment of transgression on its own, I think. Most of them involve Parisians shifting around and thinking about love a lot. Which you did yourself in your time here. How was writing about Paris in the ’80s different than the memoir you did about the ’60s and ’70s in New York?

WHITE: My best friend in Paris, Marie-Claude de Brunhoff, ex-wife of the man who draws Babar the elephant, died, and I decided to write the book as a tribute to her. Whereas my years in New York had been pretty grungy, running around having sex in trucks, in Paris I was always in a coat and tie, and many of my friends were straight, and I was freelancing for Vogue. Paris, at least my Paris, is much more bourgeois than New York.

COOPER: You didn’t mention this in your book, but did you ever meet Pierre Clementi in Paris? I’m a huge devotee of Clementi.

WHITE: No, I never did. He was the actor. He was very cool.

COOPER: He was in Belle de Jour and a bunch of experimental films. I’m kind of obsessed with him. My most recent novel, The Marbled Swarm, was set in Paris, and one of the characters is the imaginary son of Pierre Clementi.

WHITE: The Marbled Swarm is a great title. When I was a child, I loved The Marble Faun by Nathaniel Hawthorne. The reason I liked it was because it had a beautiful binding. When you’re a kid, you like books because they’re pretty to look at, and this one had a white calfskin cover and gold edges. That was enough to make me love it.

COOPER: I hear you’re writing a novel now that involves a French male model.

WHITE: I’m trying to. It’s about a model in the late ’70s who comes over from France to New York. He’s sort of a Dorian Gray figure; he never gets older, like how Brad Gooch never ages. He falls in love with some boy, and the boy says, “Oh, I could never go to bed with anybody over 25,” and he’s already 40, so he has to pretend to be 25. I think it’s a fun idea where you have to disown all the pop tunes of your own era, all the movies and everything that defined your time. You have to pretend you don’t recognize any of that. I’m also supposed to be writing another book about Mozart’s librettist, Lorenzo Da Ponte, but all I do is sort of read books about him, and I never write anything because I can’t figure out how to do it. Sometimes I think I’m too un-daring. I should be more daring and write some crazy thing. I’m always too conventional.

COOPER: I always wanted to do this thing where I wouldn’t write a book. I would just talk about a book and someone else would go and write it and I could go back and fiddle with it. Like the way sport stars do.

WHITE: That’s a really good idea. I used to think that I could be successful if I pretended to be a 23-year-old black woman. I wanted to find a young black woman who would be willing to go in on this with me. I would write her novels, and then she would do the touring. I always thought I was too old and the wrong color.

COOPER: [laughs] It’s not too late. It’d be very controversial, that’s for sure.

WHITE: Isn’t it weird how there are so few black people in Paris? Well, of course there are Africans.

COOPER: Where I live, in the 10th, has been for a while kind of the neighborhood for the African immigrant community. In the years that I’ve lived here, it’s become super-trendy and very fashionable, but they’ve managed to hold on.

WHITE: Do you ever miss America?

COOPER: I do. I just mostly miss Los Angeles, but I go back there and visit. I miss my friends. I’m sure you probably have the same thing.

WHITE: In my day, if you stayed out of America and went back no more than 30 days of the year, you didn’t have to pay any American taxes. I saved so much money that way. Is that still the case?

COOPER: Yeah, but unfortunately that isn’t true for me. I’m just a tourist here. I don’t have a visa or anything.

WHITE: I was just a tourist, too. I was a tourist for 15 years.

COOPER: You were so lucky to get the little apartment on Île Saint-Louis for so much of that time.

WHITE: I had a friend who worked for NYU who had a kind of pied-à-terre, so he let me stay there. I was only supposed to stay a couple months, and I stayed for eight years, so I think he was kind of pissed off because he wanted to use the place. I just loved it. It was so mysterious and always so foggy and cold.

COOPER: Can you still stay there when you visit?

WHITE: No, I don’t have any home base in Paris anymore. I’m too poor to be able to afford it. People always say, “Do you keep an apartment in Paris?” And I say, “Are you kidding? I can’t keep anything anywhere.” I was put up in a hotel the last time I was there, just last September. I stayed at the Lutetia, which is where the Nazis stayed during World War II.

COOPER: I live in an artists’ residency building near the Gare de l’Est. That’s the only reason I can afford it here. It’s called Centre les Récollets. It’s very nice. It used to be a convent, so it’s this crazy old building that was once a big squat in Paris—I think that’s what it was when you were here.

WHITE: Do you have a lot of sex in Paris?

COOPER: Me? No. [both laugh] I never did. I write about it a lot, but I don’t do it as much as I write about it.

WHITE: I don’t think I do it as much as I write about it, either.

COOPER: Yeah, it’s weird, right?

WHITE: We’re always too busy writing about it to do it. But there used to be this great sauna in Vincennes, the last stop on the metro, for older men and the young ones who liked them. It was really fun.

COOPER: Oh my goodness. I haven’t heard of that. WHITE: Oh yeah, you go down a narrow entryway, and it’s all tiled. It was on three floors and full of cute young people who liked older men. Thank god for them!

COOPER: The one that everyone goes to now is called Sun City. I don’t know if that was around when you were …

WHITE: No.

COOPER: Every time I talk to someone who’s gone out to look for sex, they’ve gone to Sun City on Boulevard de Sébastopol.

WHITE: I used to live not too far from you on the Rue des Lombards and the Rue Saint-Martin. The Rue des Lombards was interesting because it was the street of old whores. There were all these ladies in their seventies pottering around with these hot, young Arab boys running after them. It was great.

COOPER: That still exists. They’re in the process of passing this new law now in France, which basically fines and criminalizes buying prostitutes. There are actually protests in the street about it at the moment because the government is trying to pass this thing that would decriminalize prostitution and criminalize people who paid for them.

WHITE: It would criminalize Johns and decriminalize prostitutes? That’s interesting. What was shocking to me in the ’80s was that French law really went after the pimps. I knew someone who had a call-boy service, and he was sent to prison for years for proxénétisme, whereas the boys got off with a fine.

COOPER: You said in the memoir that the French, unlike American audiences, weren’t really taken with “gay fiction.” They saw it as a fad, whereas Americans really took it seriously as a genre. Do you think that’s changed at all? Or is so-called “gay fiction” in America alive and well?

WHITE: There’s definitely gay literature in every country still flourishing. All you have to do is attend the Lambda Literary Awards in New York to see how intense and exciting LGBTQ writing is. In Ireland there’s Colm Tóibín, in England there’s Alan Hollinghurst, in Italy there’s the great Walter —and in each case, these are among the best writers of any sort.

COOPER: I remember the last time I saw you was in Paris from across the room at the Alain Robbe-Grillet memorial. I had to duck out early before I had a chance to say hi.

WHITE: Oh, yeah. I like his wife, Catherine Robbe-Grillet. I think she’s so nice.

COOPER: Yes, she’s a friend. She actually collaborated on one of the pieces I did with Gisèle Vienne. She is quite a character.

WHITE: I saw her at a party in Paris just this past September. She said, “I have a bone to pick with you.” I was terrified she’d criticize my book, because she’s in it. She said, “You say I bring all of these glamorous society people out to my castle and that I beat them. But it isn’t just society people, it’s everybody.” [laughs] I think she’s so great. The French use the word people to mean celebrities. Je n’ai pris pas seulement les people.

DENNIS COOPER IS A WRITER, EDITOR, CRITIC, AND PERFORMANCE ARTIST. HIS LATEST WORKS INCLUDE A NOVEL, THE MARBLED SWARM, AND A FULL-LENGTH COLLECTION OF POEMS ENTITLED THE WEAKLINGS (XL).