Discovery: Griffin Newman

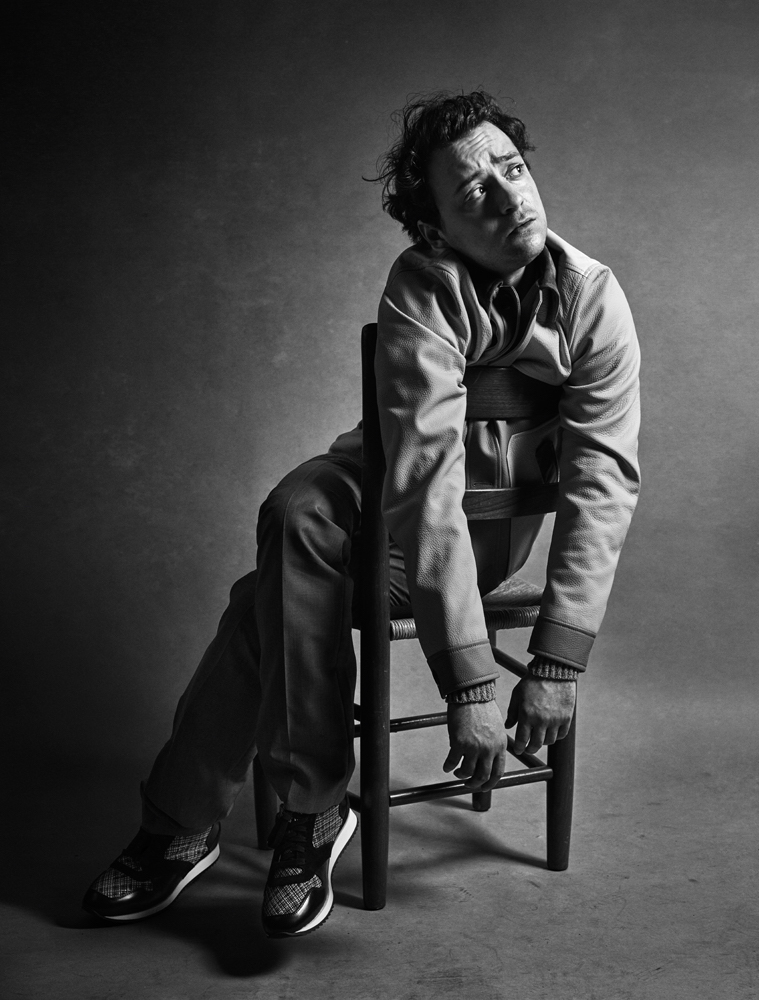

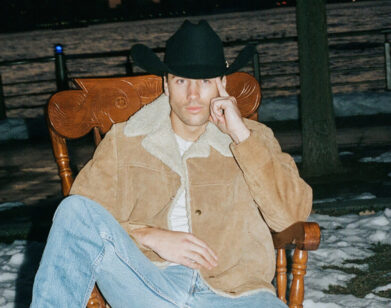

GRIFFIN NEWMAN IN NEW YORK, JANUARY 2017. PHOTOS: DAVID NEEDLEMAN/JONES MANAGEMENT. STYLING: SAVANNAH WHITE. GROOMING: LAURA DE LEON/JOE MANAGEMENT USING CHANEL. RETOUCHING: FEATHER CREATIVE.

Griffin Newman is a film nerd. When he’s not acting in television series like Amazon’s The Tick or TBS’s Search Party, or performing stand-up comedy, the 28-year-old hosts his own podcast through UCB, Blank Check with Griffin and David. Newman and his co-host David Sims spend each two-hour episode discussing a film of the past or present, from Suicide Squad to True Lies. “I think movies are kind of undervalued today,” Newman explains when we meet at a café in New York City. “I don’t know if it’s stupid or sentimental of me to position movies as the underdogs, but I feel like, especially in our generation, TV has become the more dominant storytelling form, and people engage more critically with TV than movies,” he continues. “The critical conversation that happened with movies in the ’70s—cultural arguments over whether a movie was harmful or progressive—as a dork, I fantasize about that being able to happen again.”

Raised in New York, Newman has a long family history with the arts. His father is producer Peter Newman; his mother, Antonia Dauphin, who is now a casting director and aspiring feature filmmaker, was featured in Interview‘s March 1982 issue as an actor to watch. Then there are Newman’s maternal grandparents, French actor Claude Dauphin and Deauville Film Festival representative Ruda Dauphin, and his younger brother, James, who starred in the U.S. remake of Skins.

In spite of his early exposure to the entertainment industry, Newman’s journey to the plum part he plays in The Tick was not as smooth or speedy as you might think. Though he auditioned on-and-off as a child, and was profiled as a stand-up comic in The Observer at the ripe age of 12, he did not sincerely begin acting until he dropped out of Cal Arts as a freshman. Then, he spent several years climbing up the ladder of bit parts and near-misses. “Most of the acting parts I had before this year were playing the milquetoast, put-upon assistant,” he recalls. “I had years where I pretty much always played the assistant or secretary or adjunct. My job was to stand next to whoever the movie or TV star was, deliver a bunch of exposition, and fuck some stuff up. Be awkward. Be uncomfortable. Be nervous. I used to joke that there was always a scene where someone insulted me to my face, and I was good at playing that moment of, ‘No offence taken.'”

AGE: 28.

HOMETOWN: New York, New York.

CHILDHOOD DREAMS: I was always single-mindedly focused on movies, TV, plays, and comedy as a child. That was the only thing that made sense to me. It was a thing my teachers would bring up in parent-teacher conferences: “Your son can’t talk about anything else. You maybe need to find a way to get him interested in other things.” I would steer any conversation back to some piece of pop culture ephemera. I remember a point where my parents banned me from talking about movies for a week. They were like, “We want to see if you can talk about anything else,” and I really couldn’t do it. I took kid movies more seriously than anyone else. I was thoroughly obsessed with whatever the kid movie du jour was, but also really obsessed with the production and the development and all that kind of stuff. Toy Story was my major obsession. I had this coffee table book that I made my parents buy about the production of Toy Story. It was this very dense, adult book that was very dry about the development of a computer-animated movie. I would read that to myself to fall asleep every night. It was talking about the production designer and their rendering software.

STAGE DEBUT: I was [also] very obsessed with The Muppet Show as a child. It presented this bunch of broken creatures that struggle to put on a show together, and is so based in vaudeville comedy troops. That was always kind of my thing. I wanted to be in that world—the hubbub of what it feels like behind the stage of The Muppet Show. There was this program in New York City called Kids ‘N Comedy, which still exists, where they rent out comedy clubs once a month and have kids perform. I made my dad take me to see one of those shows. I had always wanted to be performing, and I went to a lower school that didn’t have a theater program, so there wasn’t really any outlet for me. I would get really jealous when I saw kids in movies or TV shows. My mom especially was very adamant about not wanting me to become a child actor, for all the obvious reasons. But I saw this show with my father, which was these kids performing, and it felt like a reasonable, contained enough thing. I did get some press from doing that. There started being offers to audition—people would come around [to shows] when they were looking for precocious kids—but I never really got anything.

I stopped stand-up when I was 13, and I started again when I was 19. At first, my whole stand-up routine was based around me being the most depressed guy in the world—I did this Eeyore-meets-Fozzie Bear routine where the bit was that my jokes weren’t funny because I was actually maybe on the verge of a nervous breakdown. It was half a character, but I had to psych myself up into feeling that miserable every show in order to play that role. It ended up being so exhausting. I wanted to see if I could get on stage as myself and just say things.

FIRST ADULT ROLE: When I dropped out of college, my first job was a pilot for Showtime that wasn’t picked up. Tim Robbins directed it, and it was Tim Robbins, Ellen Burstyn, and Tim Blake Nelson—all these crazy people. It was the one year that Showtime didn’t pick up any series. I was like, “Oh, I’ve made it,” and everyone was like, “You’re set.” And then it belly flopped. It just disappeared.

THE LEARNING CURVE: I came to realize that the best thing that can happen as an actor is to have a couple of really big, high-profile failures, because you get to a point where you are just very sober and focused on the things that you can control—your own work—rather than thinking about what something is or could be. I always learn best through failure.

I got fired off a sitcom where I was supposed to be one of the leads. There’s what they told me was the reason and there’s what me at my most paranoid wants to believe is the reason. The reality is probably somewhere in-between the two. We shot a pilot for a network, and then a different network picked it up and wrote my character out of it. I knew that the new guy was playing a totally different character than I had played, and I couldn’t play the character the way it was written. It was no longer my type. But in everyone else’s eyes, I was replaced. That was a hard one. It was a multi-camera show, so a combination of stand-up and the on-camera acting—acting for the camera and being in a moment and reacting and listening to your scene partners, but also playing to the audience and getting that immediate feedback. It felt like I did well. Sometimes you don’t know, but I got the laughs and I felt like it was working. It felt like there was this currency that was kind of objective—when I said the lines, people laughed. [After] there was a year and a half of me just lying in bed awake every night going, “Could I have been funnier? Is there a point where I could’ve killed to a degree where they wouldn’t have questioned me?” I definitely felt for a while that was an albatross around my neck—my biggest credit was being fired from something. Certainly within the comedy community, that’s what I was known for, for failing. People try to tell you, “It’s great that you got that far,” but the scary part is, what if you don’t get that far again? A lot of people don’t get one shot—to get two is very rare.

Then I did this movie Draft Day, and when they were test screening it, it was playing really well and my character was scoring really well. It was that weird phenomenon of, I go to L.A. for the premiere of the movie on Monday, I spend Monday through Friday going to meetings and auditions where, for the first time, people are like, “We saw you in that movie. You were really good in that!” Then, on Friday when the movie came out, they knew by that afternoon that it wasn’t opening well.

I’ve had a couple of times in my life where everyone has told me “it’s” about to happen, whatever “it” is. For me, I would just like to continue working. After going through the tunnel of being super cynical about it, or being super depressed and fatalistic about it, I feel like I’m just now clear-eyed.

THE ART OF AUDITIONING: I like doing tapes, and I feel like I’ve gotten very strategic about it. I got The Tick off of tape. I didn’t do a live audition for them until my final screen test. It certainly helps if the person you’re sending the tape to is someone you’ve met in person. I feel like a big part of this isn’t just how you act, but that they’re getting some sort of vibe from you: “Oh, this doesn’t seem like a crazy person. This seems like someone I can recommend as a professional who’s sane and responsible.” Whenever I went to L.A., I would always try to just go out for whatever auditions I could, even if I wasn’t right for them, just to meet casting directors face-to-face.

I do my tapes at my manager’s office. Over the last ten years, whoever is the newest employee sort of has the short straw and has to do it with me. When I used to do self-tapes, I used to do them with my mom. Most things, especially when I was 19 or 20 and going out for high school stuff, are either romantic scenes—you’re the nerdy boy talking to his crush girl—and I’m playing that with my mom, or it’s two horny 15-year-olds talking about sex, and I’d have to do that with my mom. Then my mom would always have notes that only a mom would have: “Don’t you think your face is doing a weird thing there? Can you stop doing that weird thing?”

THE RIGHT ROLES: Search Party and The Tick are my two favorite things I’ve gotten to do, and my two favorite characters I’ve gotten to play. The way they were written, they avoided being the stock, one-dimensional versions of how those people are usually portrayed. Both of those characters are, for me, dudes dealing with mental illness that’s manifesting in very, very different ways. It’s easy on other shows to just have someone be crazy or sad or creepy, and be dealt with as a side character to get reactions out of the main character rather than an actual person who’s going through their own thing. I loved that neither of those shows over-explain what’s going on with the guys—there’s a lot of room for interpretation. The Tick presents this broken guy—the least heroic person you’ve ever seen—and the larger goal is that he’s going to come into this position as a superhero, and hopefully make a different archetype for what a hero can look like and act like and think like.

Search Party‘s the opposite; this character is kind of a villain, and it would be very easy to make him a monster, but for me at least, the boy’s mentally ill, and his long-term girlfriend, who was having an affair, just disappeared. This is a deeply paranoid guy, who’s going through a really traumatic incident that he’s not psychologically equipped to deal with or process. On top of that, he’s now put into this weird mousetrap that Dory’s constructing, in which she’s viewing everyone as a plot point or a character, and he’s not. He’s a real human being and it’s dangerous to do that to him. But I love that the show doesn’t try to argue that he’s secretly a good guy underneath it all, or try to argue that he’s just a bad dude. It’s such a bold move in a show that is one contained narrative to give an entire episode over to a new character who’s not part of the main cast. When he’s drunk and he’s vomited everywhere and he gets into this cab and leaves, you have to wonder what happens that next morning when that guy wakes up. Because he still doesn’t know how to be a functional human being. He’s going to keep on struggling on a day-to-day basis.

THE PILOT EPISODE OF THE TICK IS CURRENTLY AVAILABLE TO STREAM VIA AMAZON, WITH MORE EPISODES IN THE WORKS. SEARCH PARTY HAD BEEN RENEWED FOR A SECOND SEASON. TO KEEP UP TO DATE WITH THE REST OF NEWMAN’S WORK, YOU CAN FOLLOW HIM ON TWITTER.