Cyrus Grace Dunham Tells Rowan Blanchard To Flush Her Writing Down the Toilet

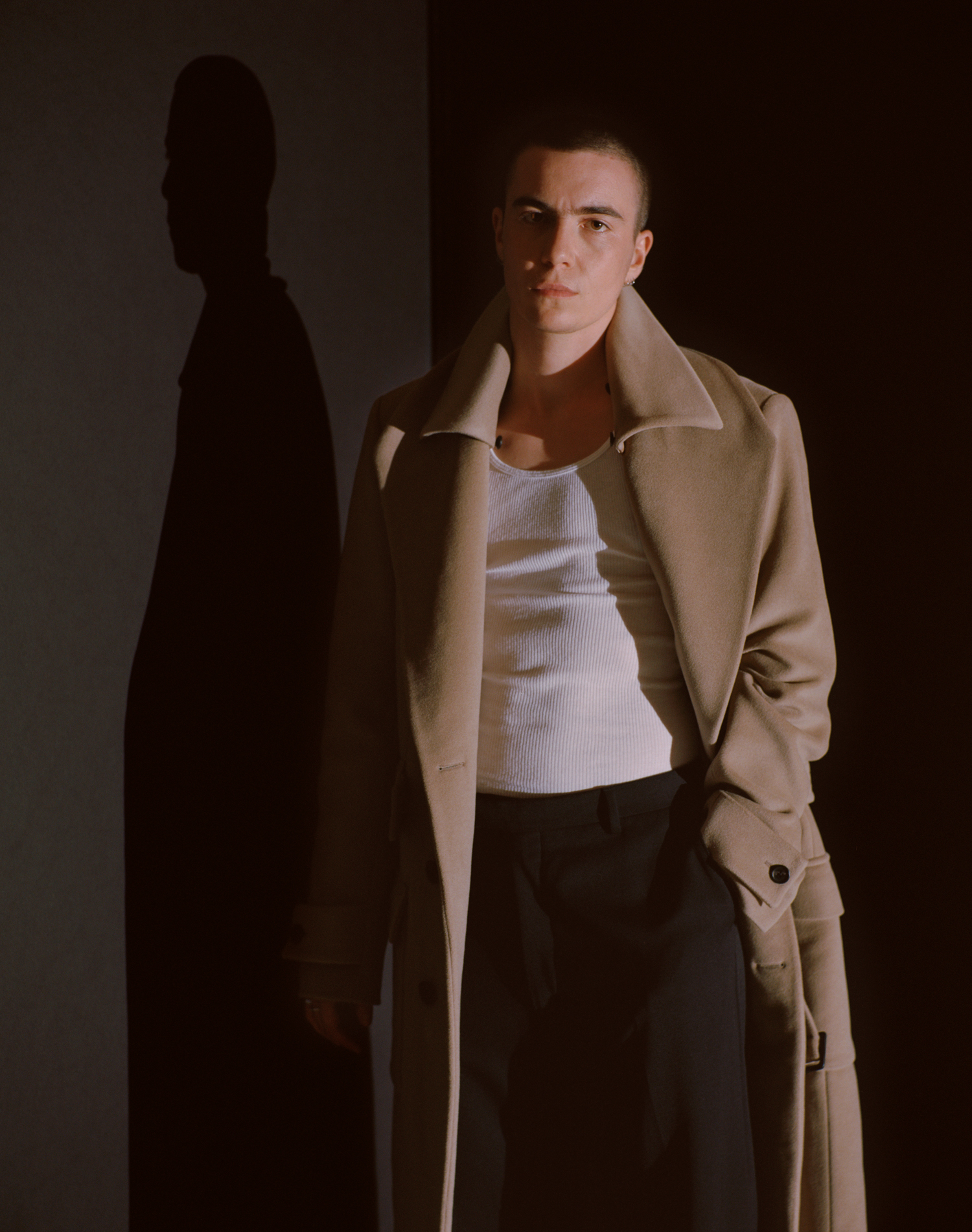

Coat, Top, and Pants by BOTTEGA VENETA. Gloves by HERMÈS. Boots by THE FRYE COMPANY CLIPPING.

“Your body is a battleground.” We’re all familiar with the potent political adage. And yet, for the queer body, it’s doubly apt—a war zone between not only the self and the outside forces trying to control it, but also the internal conflicts, repressions, indeterminacies, hard wins, and uncertain gains that play out between the brain, hormones, genitals, and heart. Perhaps no writer has been able to record this fraught state of being so acutely and sensitively as Cyrus Grace Dunham in their new debut memoir, A Year Without a Name (Little, Brown & Co.). Yes, Dunham is the younger sibling of Lena and the child of the artists Laurie Simmons and Carroll Dunham, but this is not a story about the gilded trappings of inherited fame (although the family does pop up in supporting roles). Rather, the memoir concerns Dunham’s real-time journey of transitioning roughly between the dates of January 26, 2017, when they meet a love interest named Zoya on a trip to India, and September 12, 2018, when their father first addresses them as “Cyrus” and not as “Grace.”

So many memoirs run on the seemingly preternatural sureness of their narrative voices. Much of the poignancy of Dunham’s writing resides in the author’s willingness to question their answers, their weighing second thoughts and changes of mind, and their acceptance that there are few absolute conclusions to be drawn about our deepest selves. It is a brave, purposefully untidy exploration of a young identity coming to terms with itself, body and soul, with a lot of earned observations along the way. “If the two poles of existence were dedication to family and dedication to the romantic, it was safer to choose the latter,” Dunham writes midway through. “At least my life would have a trajectory of differentiation: from loyal daughter-sister to lover. As a lover, I could be a boy.” In their first interview on the book, Dunham speaks to their friend, the actress Rowan Blanchard, about keeping a diary, being drawn to taboo, and why some of the best writing gets flushed down the toilet.

———

ROWAN BLANCHARD: I finished your book this morning. It’s so good. It must be so exciting to see what you wrote in print.

CYRUS GRACE DUNHAM: One of my favorite things about books, especially when so much of what we read is immaterial or mediated by the internet, is that you can hold them. It’s an object you get to have and put your hands on, which can make for a really intimate relationship. It means so much to me when people give me a hard copy of something they wrote. I feel like I get to have this physical, tactile relationship to it. So it’s been exciting to finally get to share my book. But in other ways, it’s scary, because I worked on it for so long and many friends were a part of the process and even became characters in the story. Writing it was intense, and I edited and changed a lot after I had conversations about parts of it with friends. So there was a lot at stake.

BLANCHARD: Whenever you write something down, it’s your truth. But it can be complicated when you write about other people. When did you decide that writing was going to be your primary form of expression?

DUNHAM: Before I even knew how to spell, I would just write and write and write. It was all nonsense, but I produced pages and pages of scribble, as if I were journaling. I’m sure I was translating something that was happening inside my head. So much of my childhood and adolescence was spent trying to work out this really intense divide between my external reality and my internal one. Later I wrote confessions about my sexuality or my desire on pieces of paper, and then burnt them or flushed them down the toilet to dispose of them. I couldn’t fully let myself record what my actual experience was because I was so afraid of putting it into language and having it witnessed by other people.

BLANCHARD: But you overcame that.

DUNHAM: I love the control derived from writing. Wielding language like a tool has always been fulfilling to me. For example, I was really into debate in high school. That involved having control over language and it made me feel really powerful. In my more recent years, I’ve been able to connect to writing as a way of processing my own internal emotions. That’s a huge part of what I taught myself in writing this book: I can use language to process all of this shit that I had stored inside myself.

BLANCHARD: I feel similarly in the sense that words have always felt like something that let me decide things about myself without always having to explicitly share them outwardly. Keeping a diary feels so significant to me.

DUNHAM: Have you always kept a diary?

BLANCHARD: Yes, always, and I’ve recently been trying to get back into it. It keeps me sane and in touch. Processing my own feelings is a big part of how I understand what is going on in the world. Lately, though, for some reason, it’s been harder to connect with writing in that way.

DUNHAM: I often stray from my journal or diary practice, then I remember that there are so many people who I’m constantly in touch with through language and dialogue. So it’s like, “Oh, I actually have dozens of diaries and journals existing concurrently, based on whoever I’m in correspondence with.”

BLANCHARD: It’s always been easier for me to write about things if I address it to someone—even if that person will never read it. I’ve always fantasized about the idea of having a pen pal that I’d never met, and writing them really detailed letters without ever facing the person. It’s like therapy or something. I’m curious about the books that informed or shaped how you felt growing up.

DUNHAM: I read through this almost dorky lens of fate. We pick up books or encounter certain texts at certain times in our lives because we’re open to them or because there’s space for us to receive them. Pretty much everything we read has the capacity to teach us something, even if it’s teaching us about the ways that we don’t want to be in the world or the things that we don’t believe in. I very rarely have the experience of reading something and not being impacted by it. A lot of the things that have impacted me most have come in strange or unexpected ways. I will say that because of the world we live in, and because of the type of education I had, I was given a really specific canon of literature that was extremely white, extremely Western, and a lot of it was very obviously straight. But within that, there were some texts that were extremely influential to me. I was obsessed with Russian literature: [Fyodor] Dostoevsky, [Ivan] Turgenev, and [Mikhail] Lermontov. I also loved Lolita. Have you read it?

Coat by FENDI. Tank Top by HANES. Pants by PRADA.

BLANCHARD: Not yet. But I saw it in the airport bookstore last week and I almost bought it.

DUNHAM: Honestly, I love it. It gets into risky territory, of course, but growing up I didn’t have a lot of access to queer literature, and certainly not to trans literature. So any time something that was part of the Western literary canon had an element of sexual transgression, it was extremely impactful to me. Lolita, obviously, has some very troubling scenes. It’s also intensely about transgression and perversion. As a young person, I felt like I was a disgusting man trapped inside the body of a 13-year-old girl—and I really did feel like I was a monster—so whenever there were depictions of sexual monstrosity in books, they were really significant to me. I loved Lolita so much. I also got my hands on William S. Burroughs and Paul Bowles. Many of the books I found about male sexual transgression were really significant. It’s only when I started to meet people who pulled me toward radical political lineages, particularly around the history of black radicalism and queerness, and I started getting to read people like Audre Lorde, Angela Davis, bell hooks, and James Baldwin, then I started reading things that were influential in terms of shaping my own world view.

BLANCHARD: I relate to that. Thinking back on whatever I was attracted to reading and consuming as a child who was questioning themselves in any way, I was always gravitating toward some kind of sexual promiscuity that I felt could give me less reason to question my own desires, which at the time I didn’t know were okay.

DUNHAM: Sometimes, for me, that even took the form of really explicit depictions of sexual violence in literature. The narrative we’re fed about what life looks like, which is that there are men and there are women and they meet each other and they fall in love and they live their happy lives, was just so clearly a lie. I felt that lie deep in my body. So I gravitated toward anything that lifted the lid and looked underneath it, particularly at the violence of it. We were told this vanilla story of adulthood. But you and I both know that the myth of a monogamous romantic marriage structure under capitalism is actually a deeply violent one that has been used for enormous amounts of sexual and racial violence. Of course I didn’t know that at the age of 12. But maybe kids are really fucking smart because we intuit things we haven’t been told. In reading, I was able to access some truths about the fabric of the world. Books that looked at rather than obscured how pervasive gender and sexual violence are also really tugged at me.

BLANCHARD: I definitely felt a pull toward the perverse. I felt there was more possibility for me in a world of bizarreness. This brings up something I read last week. We were all assigned The Diary of Anne Frank in school. But a friend posted a passage from the uncensored edition where Anne writes an entry about having a crush on her friend who is a girl. She writes about the fantasy of kissing her with a queer experience in mind. I can’t remember if we read this passage in school or not, but I will send it to you because it’s just so lovely.

DUNHAM: Wow, that’s so beautiful. I did not know that, but of course they would censor that entry. Childhood sexuality and victimhood are often seen as incompatible.

BLANCHARD: It just was so touching and surreal for me. I had this weird feeling of a queer déjà vu or something, not knowing if it was my own projection or I had actually read it as a kid.

DUNHAM: Did you write about taboo stuff when you were little?

BLANCHARD: I was almost too terrified to see it on a page. I was naturally really curious, but in terms of my diary, I felt like I had to mask a lot of things. I also think that a lot of those early coming-of-age impulses get experienced on the internet. As a young person on Tumblr, you get exposed to a lot, and it did make me feel like I could exist in a different world. It was too real for me in my own diary, but I could take in that sort of stuff online and in books. And I did what you mentioned doing. I would flush a diary entry down the toilet. Have you ever looked back at your old diaries?

DUNHAM: I haven’t. But it’s very clear to me, when I read old things that I wrote, that I was pretending. I remember so vividly the emotions that I was having internally, which were deep fixations or obsessions on girls that I was in love with, or these really intensive sexual fantasies. But I couldn’t put it into language because I couldn’t face it. Even reading old e-mails to friends, I can see the massive gap between what I was writing and my interiority. It makes me feel really sad. Even now when I look at pictures of myself and think about everything I wasn’t letting out, it’s just a lot.

BLANCHARD: I identify with that feeling of looking at your childhood stuff and being overwhelmed.

DUNHAM: I wonder if one day we’ll feel that way about whoever we are now. I feel like I’m reaching these new levels of transparency, with myself and others, but I have no idea how I’ll think back on my own level of openness in five or ten years, if I’ll see all of these ways that I was really shut down.

BLANCHARD: What are you hoping to get from the publication of your book?

DUNHAM: In a deep way, I hope that it will make some readers feel less alone in the challenge of trying to integrate themselves and connect to some part of themselves that they’ve pushed down, so that they can be closer to other people. I’m conditioned to want praise and I want the book to do well, but I also know that whatever that metric of a successful book might be, it’s not going to make me a happier person. I know that whatever kind of happiness or meaning I’m searching for is about the ways in which I’m trying to live a life with other people that differs from some script or expectation of what my life was supposed to look like. I’m open to what this process will be like. But it also makes me feel safe to know that if I don’t like it, if it doesn’t feel good for me, then I don’t ever have to do it again.

———

Hair: Rachel Lee using Mr. Smith at Atelier Management

Makeup: Karo Kangas using Dior Beauty at Lowe and Co.

Set Design/Prop Stylist: Maxim Jezek at Walter Schupfer

Photography Assistants: Patrick Molina and Tigran Tovmasyan

Fashion Assistant: Sienna Scarritt

Special Thanks: Milk Studios