Lights Out

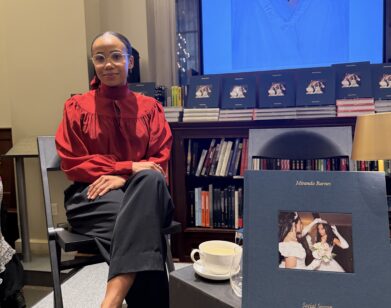

ABOVE: BRAD GOOCH IN NEW YORK, FEBRUARY 2015. PHOTO BY BRIAN HIGBEE. STYLING BY MARK HOLMES. SWEATER: LOUIS VUITTON. T-SHIRT: CALVIN KLEIN. PANTS: DIOR HOMME. WATCH: GOOCH’S OWN. GROOMING: RHEANNE WHITE FOR LAYRITE/SEE MANAGEMENT. SPECIAL THANKS: BROOKLYN GRAIN.

The moment I finished Brad Gooch’s new memoir, Smash Cut, I tried to remember the last time a book made me cry. Tear-jerking alone is not the standard-bearer of literary brilliance, but there is so much brilliance at work in Gooch’s reminiscence of life in gay, bohemian downtown New York in the late ’70s and ’80s that a reader’s face is liable to span the entire emotional spectrum before they’re through reading. The memoir charts the relationship of Gooch, then a struggling writer, grad student, and occasional model, and his boyfriend, the budding filmmaker Howard Brookner. The first half of the book is filled with deliciously decadent, fleet-footed tales of love, drugs, sex, carousing, near-breakups, and run-ins with fame. But this is a party where the lights don’t just turn off-the air is sucked out of the room. In Gooch’s visceral, gut-punching narrative, the arrival of AIDS turns the city into a cemetery. In one haunting scene, Gooch watches as a man carrying a prescription in the West Village breaks into tears: “I knew that he had just received his diagnosis and that now he was on his way.” Soon Brookner is diagnosed, and the memoir transforms into an ode on survival, sickness, devotion, tenderness, and young loss. This is a memoir that needs to be read by those who remember and those who never knew. I asked Gooch a few questions about what it was like to write it all down.—Christopher Bollen

STUDYING UNDER THE GREAT POET KENNETH KOCH AT COLUMBIA: He was a tremendous teacher. I remember I had blank-verse class with him. He came in and was talking and I realized at a certain point that he was talking in blank verse: “I came down on the street tonight on my way to work. I saw a tree and the tree was…” He was very clever. Once he said to me, “You rely too much on authority.” And that just went through my brain. I was traumatized by it.

WHETHER MODELING FELT LIKE A SIDESTEP FOR A SERIOUS WRITER:It always seems like literature’s dying anyway. So somehow it seemed that literary careers weren’t to be aspired to, in some ways. Everyone kept saying there weren’t going to be any more books. It was also a Warholian era, and I was interested in those kinds of things: in celebrity and models. At the time it was actually an art form. And a lot of us coming out of Frank O’Hara have that interest in popular culture and in writing poems about James Dean. Then I had this idea of writing a novel about my modeling experience [Scary Kisses, 1988]. I was a minor model but because I wrote a novel about it, I was forever this model-turned-writer. That’s had its problems, and probably its perks too.

WRITING THE MEMOIR: It took me a while, conceptually, to figure out how to do it. I started writing about the fabulous ’70s and ’80s. It really was fun to go back and remember that feeling of innocence and romance and joblessness of that time. It was also an amazing generation—the first out generation in some way. And specifically in writing about Howard, I really enjoyed it; it was like being back with him again after so long.

LOOKING BACK FROM A 30-YEAR DISTANCE: Someone told me that Stanislavski said to wait seven years to make a memory. But AIDS memory takes longer. It’s very difficult. But everything is so different now than it was, everything has changed. I see the Chelsea Hotel every day and it’s being re-vamped. The entire nature of Chelsea has changed, with husbands and children. You can barely believe you’re in the same place or the same person. But I felt in some way that Howard expected me to write this book, so recording him was important to me. Howard has always been floating inside of me and around me in this kind of cloud. Forever. And somehow by writing the book, which is a gain and a loss, he’s kind of become fixed…now I think about him as I wrote him.

POSING FOR ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE: When I first saw Robert he was at the Mineshaft [a gay bar and sex club in the West Village] and I was very intrigued. He would come walking through looking like a Jersey guy, in black leather—very spiffy. And then he had this line of colored handkerchiefs in his back pocket. He would kind of stride through Mineshaft. Then someone introduced us, which was exciting and disappointing that he wasn’t this Jersey guy; he was a photographer. And he said if I ever wanted to work together…. He sent me a postcard in the mail, which was a photograph of a guy with an uncut penis. When we hung out together there was always this funny erotic charge that neither of us could figure out what to do with. And that’s what happened when he took my photograph. He wasn’t a fashion photographer, but he knew exactly what he was doing. He was bold and driven by desire. He wasn’t making that up. We did that thing where we sat around and talked and did cocaine. And then he said, “let’s do the photographs.” We went to the back of his studio and he took my photograph. But at the time I couldn’t tell, is this sex or not sex? Because he was micromanaging everything, which is partly sexual. We were so stoned I couldn’t figure it out. He had this camera at his crotch.

NEW YORK IN THE ’70s AND ’80s: It was very small. Now you don’t have to come to New York. You can just go on Instagram. You can hook up with your niche through all different ways. At that time you had to go somewhere. If you were in the American suburbs, it would probably be New York. And it was a small group of people, especially in the gay aspect of it. For example, when I was a college student I was at this party, and Kenneth Koch said to me “Is there anyone you want to meet,” and I said Allen Ginsberg and John Ashbery. You quickly met everyone—it was that small. But it was also expansive because people would run around and do things that they wouldn’t dare do today in public, because someone would take their picture. Everything really was underground, and therefore it was safe.

ST. VINCENT’S HOSPITAL IN THE ’80s: I have this almost dolly track footage in my memory of going through St. Vincent’s. That floor in St. Vincent’s was safe. It was obviously sequestered, but the attitude was nurturing and loving. Howard wasn’t the only one who had a kind of guileless humor and could be flamboyant about death and not be sentimental about dying. A lot of the guys there treated death the same way. It was a kind of bravery and courage and humor and all these qualities that I wouldn’t have thought these guys had in them, having known them, but it did bring it out. And many of them were so young. That’s why the war metaphor is an apt one. It really was like going into war. And wondering what life would be like if they had lived is sort of like wondering “What if the South had won the Civil War?” What if Mapplethorpe were alive and Howard were alive? What would the world be like? Because a lot of the freer spirits were the ones who got kind of picked off by the sniper of AIDS. They were innovative and productive and serious about their art and it was also a much more politicizing time. Horny as those Mapplethorpe photos seem, they were also political. Gay identity seemed much more up for grabs back then. No one expected the emergence of a science fiction disease that killed you. It’s also not that everyone was completely innocent; there were times I remember looking around thinking, “this can’t go on”—all of the not sleeping and taking drugs and heavy sexual activity. What came to be was completely unfair, no question. But it wasn’t completely counterintuitive.

ON MADONNA, WHO WAS IN HOWARD’S LAST FILM, BLOODHOUNDS OF BROADWAY (1989): Madonna was very brave, coming up to St. Vincent’s, visiting Howard, kissing him on the lips, visiting the other patients. She had this great heart, and she’s really smart. She was an amazing figure. But that’s also the part that’s the art-and-career tragedy of it; Howard really was doing interesting stuff and these actors were really into it, and it was an exciting energy. Howard learned from Burroughs, and from Robert Wilson, and from Warhol, too. That was part of our education, growing up in New York. And Howard would have had a long, exciting career.

ON KEEPING THE NARRATIVE TIGHT AROUND HOWARD: The world became this hospital room or Howard’s apartment. I wasn’t really dealing with the larger political issues. It really had to do with him. Around someone who’s dying, there’s this intimacy, which is painful, but it’s also beautiful. It’s like some kind of endomorphin that death releases. There’s something soothing about it, as long as you stay with it. That was the most important thing going on in the world and in my life, and I gave myself to that. So, the book just reflects what happened. The world just became that, and people came into it sometimes.

REMEMBERING IN PRECISE DETAIL: I had been keeping a journal when Howard was sick, just as I was keeping a journal when I was modeling, so I had specific details. The medical part confused me at the time—it confused everyone at that time because no one knew what brought it on or how to treat it. But I also had a lot of Howard’s possessions. It was in my attic, in my Hoard file. And then, funnily enough, things would just show up, which happens when you’re writing a book. Burroughs talked about that, how writing tampers with the world like a kind of magic. So, things would pop up, that I had forgotten, like a letter from Howard or a postcard with a date to verify my timeline was correct.

HOWARD’S HERO, WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS: William was a double-edged character. It was interesting to write about him because I’m not part of the cult of Burroughs. I love his writing but personally, he could make me uncomfortable. It’s ironic that I’m writing about him and that I had that kind of up-close exposure in the first place. Back then it felt like there were two different aesthetic strains, and there were two different sides of Manhattan. It’s like Darryl Pinckney was studying prose with Elizabeth Hardwick at Barnard, while we were studying poetry at Columbia with Kenneth Koch. That was a huge difference, and never was the twain gonna meet. There was a real divide then, and we worried about these things.

BRAD GOOCH’S MEMOIR SMASH CUT COMES OUT TOMORROW, APRIL 14, VIA HARPER.