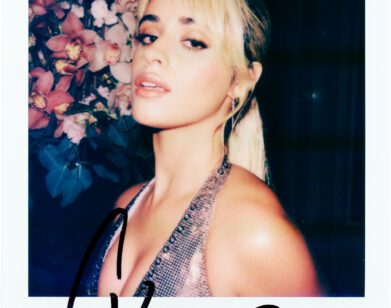

Birgitte Hjort Sörensen

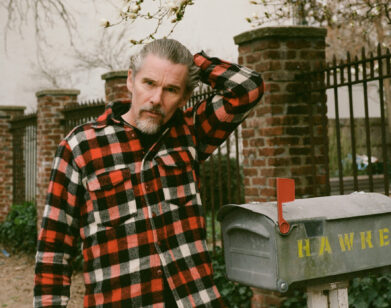

BIRGITTE HJORT SØRENSEN IN NEW YORK, OCTOBER 2016. PHOTOS: DAEMIAN SMITH + CHRISTINE SUAREZ/ANGELA DE BONA AGENCY. STYLING: JOSHUA LIEBMAN/HONEY ARTISTS. HAIR: JORDAN M/SUSAN PRICE USING BUMBLE AND BUMBLE. MAKEUP: TORU SAKANISHI/JOE MANAGEMENT USING CHANEL ULTRAWEAR FOUNDATION.

“When I applied for drama school, the idea of working as a Danish actor outside of Denmark was so foreign to me,” explains Birgitte Hjort Sørensen over drinks in New York. “Not a lot of people had done it—it had been, like, Mads Mikkleson,” she continues. “Even though I dreamed about it, I didn’t think it would be within my reach. Then when first The Killing and then Borgen became such hits, all of the sudden the scenery changed and it was a different landscape.”

Raised in Copenhagen, Sørensen’s American résumé isn’t long, but it’s impactful. Over the last two years, she has appeared as a Wildling chieftain in Game of Thrones, an unfriendly German acappella singer in Pitch Perfect 2, and one of Andy Warhol’s Factory friends in Vinyl. When we photographed her on the streets of SoHo, New York, last month, a group of ten-year-old girls immediately recognized and surrounded her, eager to know about the likelihood of a Pitch Perfect 3. On the set of HBO’s now-cancelled drama Vinyl last year, burly crew members would ask for selfies.

At the moment, Sørensen is on Broadway starring opposite Janet McTeer, Liev Schreiber, and Elena Kampouris in the Donmar Warehouse’s production of Les Liaisons Dangereuses. Sørensen plays Madame de Tourvel, the moral heart of the narrative. Though it is her Broadway debut, Sørensen has acted on stage many times before: she played Roxie Hart in Chicago in both Copenhagen and London, and worked with Les Liaisons’ director, Josie Rourke, on Corialanus at the Donmar Warehouse in 2013. “I always thought I would do lots of theater,” she reflects. “I have a strong dramatic sense.”

EMMA BROWN: Can you tell me a little bit about how you got involved in Les Liaisons Dangereuses? I know you’ve worked with the Donmar Warehouse before.

BIRGITTE SØRENSEN: I think that was a big part of it. I had worked with Josie Rourke when we did Coriolanus; we had a really good working relationship and we’ve been in contact since, trying to find another project to collaborate on. When this came along, for a while it seemed like, scheduling-wise, it would be difficult because I was still doing Vinyl at that time. But when that was cancelled, all of the sudden my fall was open. There was an auditioning process because a lot of people have to approve me, but that was definitely my way in.

BROWN: The play got such great reviews when it was on earlier this year in London—is that comforting at all or does it feel like a lot to live up to?

SØRENSEN: Probably a little bit of both. I try not to read reviews, even if I’m just going as an audience member, because I don’t like to have my opinion influenced. So I hadn’t really paid attention to that. I think that most of all I felt comforted by the fact that the writing is so strong and the fact that the producers here thought it was strong enough to bring over. And I know Josie and what I wonderful director she is. And Janet [McTeer]’s work of course, and when Liev [Schreiber] was attached as well … All in all, I felt pretty comfortable that it would at least be a really interesting working experience.

BROWN: During the preview period, how much actually changes?

SØRENSEN: Overall it’s pretty set because the play is 30 years old and it’s proved itself. There’s not a lot of necessity to change the words. We’ve maybe taken one or two out, or something like that. We’ve changed some of the mise en scène. We used to have a fight, me and Liev; I used to slap him and he used to grab me and throw me down. But because I was injured, we had to find a different way to do it, and we actually like the new way better, so we stuck with that.

BROWN: I was familiar with the story before I saw your production of Les Liaisons Dangereuses—I’d read the book and seen the Stephen Frears film—but I think I was more unsettled and upset by it than ever before. How it fits into my worldview in terms of gender politics and sexual politics has changed, even over the last five years. How do you feel about it? How has your relationship with it changed since you first saw the film?

SØRENSEN: The first couple of times I saw the film I was a kid and I don’t think I thought about that at all. I am now grown up, and therefore pay attention to those topics. I think it’s also very much a current topic in the world now—with the internet, the fear of public humiliation is so present for all of us. Janet has this fantastic speech about how, “You can ruin us with one single word,” and I think that’s even more present today. The idea of revenge porn is actually what they’re talking about and it’s a horrible, horrible thing. But for me at least, it makes me think of the play as incredibly modern and up-to-date. It’s funny, isn’t it? In some ways, I feel like where I grew up and where I am now, we’re very far away from the perception of gender as portrayed in the piece. But it still seems to play a big part. Today, we’re struggling a lot, both men and women, with finding out what we’re supposed to be. Like when you go on a first date, I always find it incredibly difficult to figure out whether I should reach for the check or not. I don’t want to presume anything, but I don’t want to be a ball-buster. A lot of rules are thrown up into the air and I think that maybe more than anything, we’re confused.

BROWN: You want the audience to be invested in and to care about what happens to Valmont and Merteuil, even though they’re horrible people. How do you get around that?

SØRENSEN: It’s my sense that audiences always love the baddies. Especially these ones that are so witty and charming and outrageously devious—everything you’re not supposed to be. I think it speaks to the basic, primal nature in us. What’s brilliant and what I hadn’t really thought about before is the intense love story that is between them. There were so many wonderful conversations that came up in-between rehearsals about how they’re actually soul mates, but they’re so damaged by all the lying and deceiving that they’ve done that they can’t form a healthy relationship; they can’t trust themselves or the other person. My concern was mostly that Tourvel would be sort of boring compared to them. Definitely the first couple of previews, I struggled so much with the fact that the audience laugh at her because she’s not in on the joke. I had put so much focus on understanding her profound sense of both religion and moral conduct and being proper, I’d forgotten that to most modern people that’s hilarious and she can come off as kind of naïve. The first couple of previews I was mortified: “You can’t laugh! It’s really serious for me!” It took me a while to figure out that that’s where I’m supposed to be. She’s not naïve, but she is guileless compared to them. She doesn’t think about deception—it’s not in her world. That made her seem purer. There’s something about Valmont and Merteuil that just make people fall in love with them because they’re so outrageous.

BROWN: I was laughing at Cécile, because she is so ridiculously naïve at times, but when I thought about it, I felt terrible. You’re laughing at this young girl for being exactly what she’s been brought up to be.

SØRENSEN: We talked about it, and the really wonderful thing is if you can get the audience to laugh and then feel bad about laughing, because then you’ve really got them. The play, it starts out really funny. For a long time it’s pretty much a comedy. And then it turns and becomes serious.

BROWN: Your parents are doctors. When you decided you wanted to be an actor, how did they react?

SØRENSEN: First off, they didn’t say much—they just supported me. My dad at one point said something about, “With your head, you should go to school,” but they never discouraged me. Probably they had concerns, but they didn’t express them. I got a pretty good break, because fairly early I got into drama school and got jobs. I think that put them at ease.

BROWN: Were you allowed to take jobs when you were in drama school in Denmark?

SØRENSEN: You weren’t allowed for the first two years—we go to school for four years. I cheated a little bit and did one day on a TV series and called in sick at school. [laughs] I had a scene with my fencing teacher, so I had to say to him, “Please don’t tell people back at school!” I think maybe the landscape is changing a little bit now because they understand that it’s a good thing for people to establish networks while they’re still at school. But that was the rule back then.

BROWN: Game of Thrones and Pitch Perfect 2 came out around the same time. Did things really change for you in the U.S.?

SØRENSEN: I’ve been very surprised at the level of attention for Pitch Perfect 2. Within three weeks or so, the episode of Game of Thrones came out and Pitch Perfect, so my social media accounts exploded right around then. I could tell on IMDb that all of the sudden I was getting more hits. But the funny thing was, we were doing Vinyl at the time and for a couple of weeks, the crew would come up and say, “I took my daughter to see Pitch Perfect 2 and she really loved it.” That was mostly women. Then the day after my episode of Game of Thrones was out, all of the really tough crew guys all of the sudden wanted pictures.

BROWN: You knew Nicolaj Coster-Waldau before you did Game of Thrones, but you didn’t have any scenes with him. Did you know anyone else in the cast?

SØRENSEN: I didn’t know anybody else involved, but I know that the writers are big Borgen fans. I think when they needed this Nordic woman I was probably someone they were interested in seeing. I did an audition, but I had sort of a head start.

BROWN: Are you okay with being cast as these sort of ambiguously European characters—whatever nationality someone needs at the time? You’re German in Pitch Perfect 2.

SØRENSEN: It’s fine. It’s funny to me sometimes that people will come up to me and say, “I met a Dutch person yesterday!” I’m like, “Okay, great!” I understand, being here, especially, that it is very far away. And because America is such a big country, I can understand that if you don’t travel you don’t really understand what is going on. I get it. I tell myself I know all about America, but I don’t; I know L.A. and New York.

BROWN: What was Vinyl like? Did you have any scenes directed by Martin Scorsese?

SØRENSEN: He directed the pilot, so I had two days of shooting with him. When we did the rest of the series, he was just producing and I saw him a couple of times. It was such an incredible project. I couldn’t believe when I got the email about the audition. Sometimes they have a very standardized way of looking—those “Please put yourself on tape for this” emails. I usually will recognize one or two names, and this was just A-list all the way. I really couldn’t believe it. I was so excited to be on board and very nervous. I dreaded that I would forget my lines. But none of that happens because Martin Scorsese is so much about the work. All the fuss around him, other people make it. He doesn’t really pay attention to it. Once I got over myself—that “Oh my God, I’m actually here”—it was very easy. I think that’s why he gets great performances, because he puts his actors at ease. I felt like I could contribute with whatever I could. It was just a small scene but I really enjoyed it.

BROWN: You said that being a Danish actor working abroad wasn’t really something that you thought was possible. Once you started working in England and the U.S., how did your goals shift? What do you want out of your career now?

SØRENSEN: I actually don’t have a specific goal in mind; it’s served me very well to keep an open mind and to see what comes my way. Pitch Perfect I would have never thought about—I didn’t know the first one. Then when I got presented with the opportunity to audition I read it and thought it was really well written, really funny. I had so much fun doing it. So you can’t really tell, I think. But I feel very encouraged that the fact that I am neither American nor English doesn’t mean that I’m eliminated from any kind of list. I think my only goal is to keep enjoying what I do. Sometimes the reality of doing this is a lot of waiting on your own, far away from home, and then one day here or there where you really get to do your work. I think for me it’s also important that I have something that I enjoy on an everyday basis. That’s ultimately why I haven’t moved here, because I still feel at home in Denmark. For me it will be about balancing interesting work and also having my home life.

LES LIAISONS DANGEREUSES IS ON NOW AT THE BOOTH THEATRE IN NEW YORK THROUGH JANUARY 22, 2017.