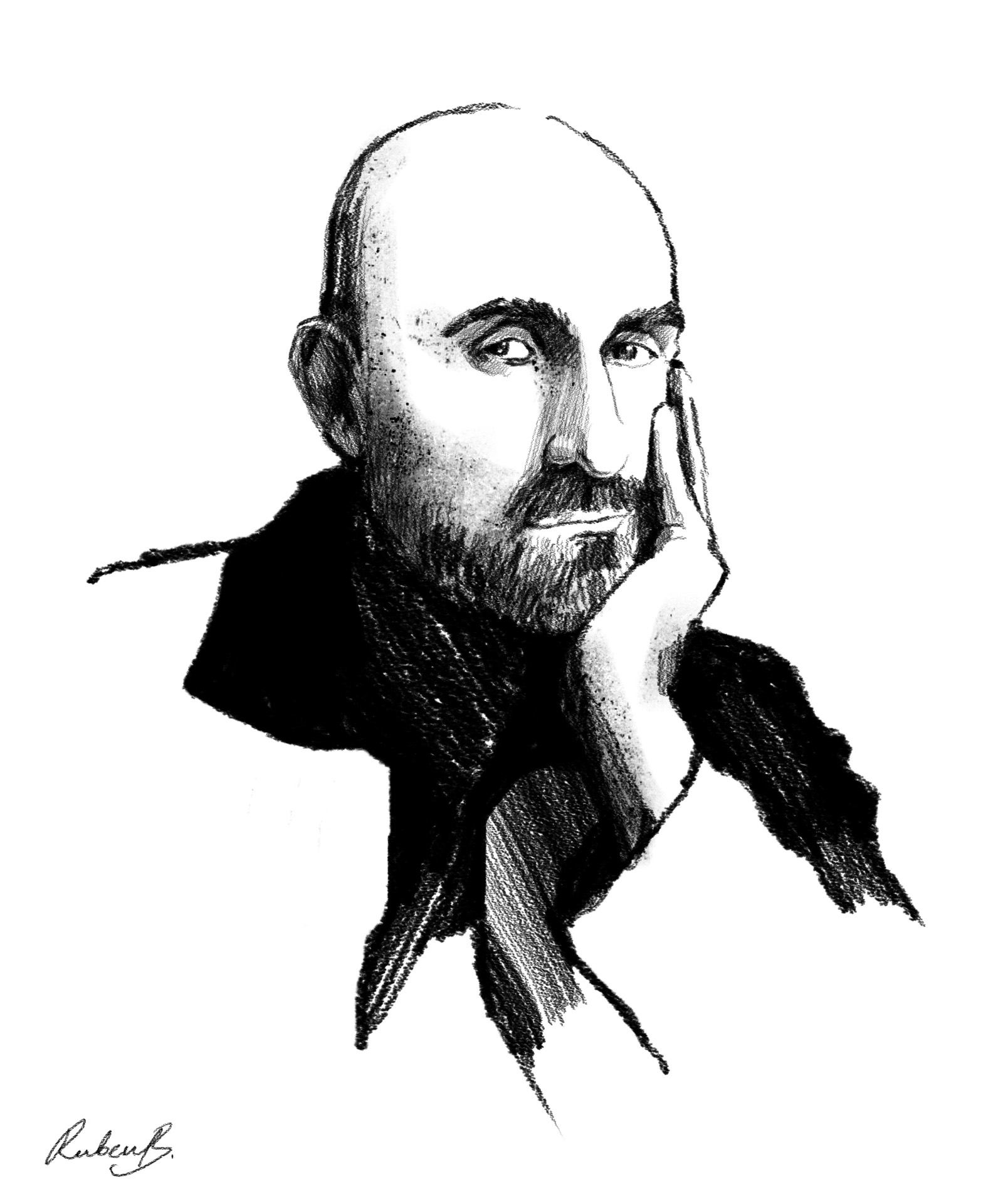

Ask a Sane Person: Hari Kunzru On the Difference Between Signaling and Seizing Change

“When you are powerless, everything you do seems in vain,” Hari Kunzru wrote in his 2017 novel White Tears. “You stow your bag, show your ticket, climb the steps. All the sinners climb aboard.” Kunzru is one of our foremost novelists on charting the ways in which society wields power and holds its volatile forces in check. Right now, the actions of the powerless do not, for once, feel in vain. The New York–based author is about to release his latest novel, Red Pill, about madness and meaning set against a writing residency in suburban Berlin. Also this fall, he’s launching his own podcast, “Into the Zone,” devoted to stories of shifting borders.

INTERVIEW: Where are you and how long have you been isolating?

HARI KUNZRU: I’m at home in Brooklyn. I have access to some outside space, and a place to work. My family’s been healthy so far and we can still make a living. We’re lucky. We’ve been doing this since early March. March 9th was the last time I ate at a restaurant. March 11th was when I last rode the subway.

INTERVIEW: What has this pandemic confirmed or reinforced about your view of society?

KUNZRU: I’ve always felt intuitively that people are connected in ways that we don’t fully acknowledge, and that the fear of collective life and collective action that’s so rooted in American culture would come back to bite us on the ass. Well, guess what…

INTERVIEW: What has this pandemic altered about your view of society?

KUNZRU: It’s changing how I think about cities. I thought people would always swarm into top-tier cities like New York, Paris, or London as a way of getting access to the absurd concentrations of capital located there. Now that we’ve been forced to create a more robust teleworking structure, I’m beginning to think that perceptions will change. No one wants to be on the subway right now. Nobody’s feeling good about their decision to spend $3,500 a month on a tiny apartment in a city with none of the pre-pandemic activities and attractions. I think the pandemic is a force for disaggregation. Months of “social distancing” will change us in profound and subtle ways. Rich people will find further excuses to disconnect. Young PMC types will look with interest at smaller communities. I think New York and other “world cities” will still be hubs of activity, but I’m not sure the model of a dense downtown central business district will survive everywhere.

INTERVIEW: What is the worst-case scenario for the future?

KUNZRU: The U.S. becomes an autocracy, and devolves into a weak and fractious patchwork of jurisdictions run by more or less rapacious oligarchs who conduct a losing war with China, first cold then hot. Human rights become a quaint idea. The environment collapses, and the resulting massive migrations of people lead to vicious authoritarian regimes taking control in richer countries. Genocidal wars are fought over water. The Tibetan plateau is a global flashpoint. New pathogens emerge out of the melting permafrost, killing millions. Life becomes hellish for all but the very wealthy. For the masses, the future looks like an insect world of starvation or highly-surveilled shock work; for the few, a melancholy decadence conducted behind high walls. I always thought the shit would go down when I was young and strong. These days I’m just hoping I won’t spend my old age picking through the ruins of my city looking for expired canned food.

INTERVIEW: What good can come out of this lockdown? Are there any reasons to hope?

KUNZRU: There are reasons to hope. We’ve paused our lives, and this has given people a moment of reflection that I think will have global consequences. For example, the air has been good here in New York. People will notice the reduction in air quality as the traffic returns. In Delhi, the world’s most polluted city, that bad air will be felt like never before and perhaps people won’t put up with it. I’m beginning to read commentators saying that the pandemic is making certain sorts of fossil fuel extraction non-viable, and that some production may not come back. If the pandemic helps us speed up the transition to a low-carbon economy, that’s a silver lining.

INTERVIEW: What has been your daily routine during this time?

KUNZRU: The dirty secret is that it’s not too different from what it was before. I’m obviously not very social.

INTERVIEW: On a scale of 1 to 10, what is your level of panic about the current state of the world?

KUNZRU: I suppose I’m going to quibble about the use of the word “panic.” I’m really alarmed, but determined. Right now, it feels as bad as it did in 2016, in some ways worse. Even if Trump goes, we’ve spent the last half-decade pissing around instead of future-proofing our society. I’ll say 8, right now. I’m sleeping okay, and not having to do breathing exercises.

INTERVIEW: Do you think there is hope for true racial equality in the United States? What do you think is the first step in that goal?

KUNZRU: Yes, I do. The first step is to make Stephen Miller pick up trash every Saturday wearing an orange jumpsuit while children laugh at him.

INTERVIEW: How can America work to ensure more equality and justice on a day-to-day level?

KUNZRU: I think there’s a lot of meaningless signaling. I don’t give a damn if a brand blacks out its IG. The real work is conducted through simple and rather concrete things. Who gets paid? Who gets credit? Who gets heard? Who is in the room? We can all look around in our work and social lives and ask if there are people missing. And if there are, we can take steps to find out where they are and bring them in.

INTERVIEW: Do you think protests are effective tools for changing the system? How does it make a difference in the long term?

KUNZRU: There are limits to protest, of course. I remember in 2004, after so many of us had gone on to the street to protest the invasion of Iraq, feeling so disheartened that it happened anyway, and that it was exactly as bad as we’d warned, in exactly the way we’d predicted. We’re still living with the consequences of the failure of our leaders to acknowledge that protest. But the protests following the murder of George Floyd are producing change. Look at the bans on chokeholds and the critical look at police budgets. The protests have also exposed the raw edges of the power structure. For now, at least, those who govern us do so by our consent. By coming out on to the street and being disruptive, we remind our representatives that they serve at our pleasure, not the other way round. These communal experiences—which are, of course, also a massive release from the tension of Covid, and sadly probably a vector for its future spread—remind us that we are powerful. They are a “time of chance,” in the ancient Greek sense of kairos, a moment in which we can remake the future, seizing the opportunity to change.

INTERVIEW: How do you personally channel your anger? Do you find anger to be a useful emotion?

KUNZRU: I’m trying to put it on the page. It’s the only outlet I have that has a chance of being meaningful. Yes, anger is useful. Black humor is also useful. So is love.

INTERVIEW: Who are the young leaders that inspire you?

KUNZRU: All the anonymous organizers and protest leaders who will never be recognized, or pose for photo shoots or be held up as role models, but who are exhausting themselves trying to make this happen. Thank you, one and all.

INTERVIEW: What’s the next step after protests in the streets? Where does the righteous rage go?

KUNZRU: For me, it goes into the coldest and clearest analysis of the situation I can make. That’s all I can do. I’ll write what I can, comment, link to information, try and help people decide for themselves what these times require. I think we need to work toward November, and focus on surviving until then, dealing with whatever flood of shit is going to come at us during the election. After that, let’s see. I’m taking things a day at a time right now.

INTERVIEW: How do we address the conversation about race directly?

KUNZRU: I think there’s altogether too much talk. Try not talking. Try silently doing stuff. See how that feels.

INTERVIEW: What thinker have you taken comfort in of late and why?

KUNZRU: Comfort? That’s a particular question. I’ve fantasized lately about being a hermit. There’s an ancient Chinese poet called Han Shan (“Cold Mountain”) who writes about retiring to a place also called Cold Mountain to contemplate the world. I have the poems in a beautiful translation by Red Pine. It’s pure escapism, of course.

INTERVIEW: If 2020 were a song, which song would it be?

KUNZRU: “Baby Shark” played very loud on repeat for 24 hours a day. This is, as they say, the stupidest timeline.

INTERVIEW: Where did we go wrong? Like, what was the exact moment?

KUNZRU: Probably with the development of agriculture.

INTERVIEW: Which (admittedly totally unqualified) celebrity would you trust with the planet’s future?

KUNZRU: I thought the Tiger King guy was already in charge.

INTERVIEW: What’s one skill we should all learn while in quarantine?

KUNZRU: Compassion.

INTERVIEW: What does our future as a nation look like?

KUNZRU: Oh, look! Over there! Is that an eagle? Sorry, what did you say?

INTERVIEW: What prevents you from giving up hope in the human race?

KUNZRU: I have children. I have to be hopeful.