How Siouxsie and the Banshees Saved Sue Webster’s Life

A typed letter to David Bowie. A copy of Mein Kampf. A paint-splattered pair of Adidas Originals. Sue Webster has spent a lifetime amassing cultural ephemera, first as a teenager growing up in Leicester, England, and then, along with her partner and ex-husband Tim Noble, as a leading artist of the post-YBA generation. This visual autobiography is spectacularly displayed in Webster’s London studio, spread across an imposing wall that she has labeled “The Crime Scene.” The items, interconnected by a network of pink strings, seem to map out a grand theory: Everything leads back to Siouxsie and the Banshees. Webster discovered the goth-rock pioneers, whose first four albums are displayed in the center of her mosaic, when she was a teenager struggling with mental illness. The band, and specifically their otherworldly frontwoman Siouxsie Sioux, became something for Webster to cling to while she recovered and found her way. Her reverence for the band is the subject of her new book, I Was a Teenage Banshee, a catalogue of her obsessions and inspirations. Here, the artist recounts the stories behind some of her Siouxsies.

A typed letter to David Bowie. A copy of Mein Kampf. A paint-splattered pair of Adidas Originals. Sue Webster has spent a lifetime amassing cultural ephemera, first as a teenager growing up in Leicester, England, and then, along with her partner and ex-husband Tim Noble, as a leading artist of the post-YBA generation. This visual autobiography is spectacularly displayed in Webster’s London studio, spread across an imposing wall that she has labeled “The Crime Scene.” The items, interconnected by a network of pink strings, seem to map out a grand theory: Everything leads back to Siouxsie and the Banshees. Webster discovered the goth-rock pioneers, whose first four albums are displayed in the center of her mosaic, when she was a teenager struggling with mental illness. The band, and specifically their otherworldly frontwoman Siouxsie Sioux, became something for Webster to cling to while she recovered and found her way. Her reverence for the band is the subject of her new book, I Was a Teenage Banshee, a catalogue of her obsessions and inspirations. Here, the artist recounts the stories behind some of her Siouxsies.

———

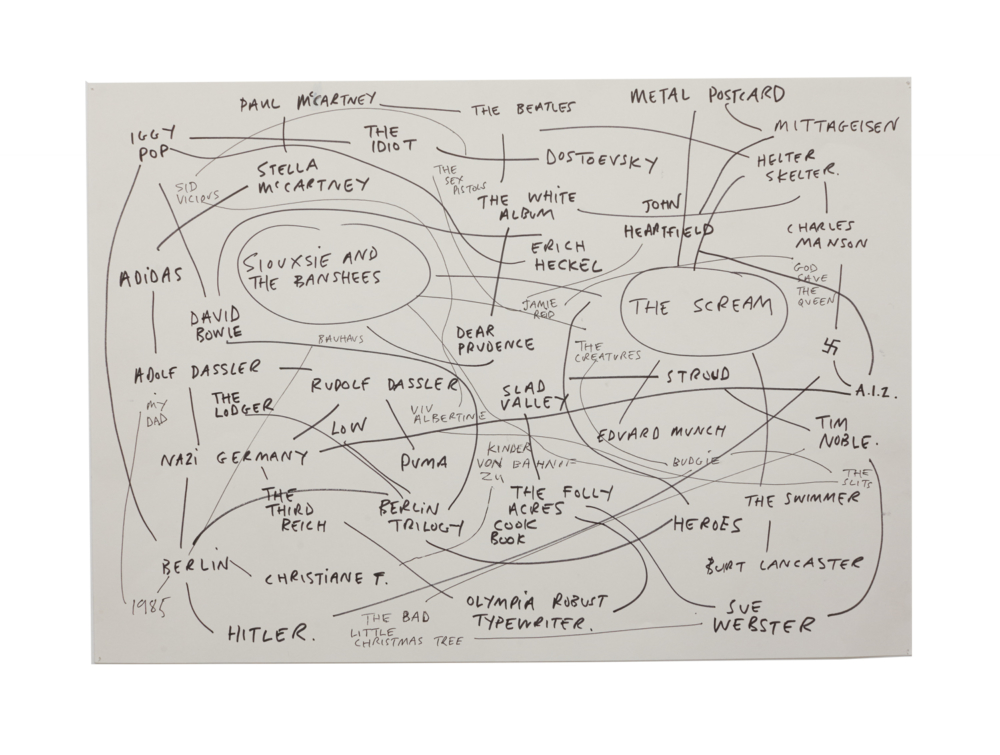

“I used to do these when we were very drunk at restaurants. I’d draw all over the table when I was trying to explain something to somebody. I would say, ‘I’m connected to Hitler and I can prove that in three degrees of separation.’ Then I started doing them to try to connect myself to Siouxsie and the Banshees. I had them all over the walls, and somebody came around for a visit and said, ‘That’s a spider graph.’ I’d never heard that before. My name is Webster, but when I was a kid at school people used to call me Webby, and me and my sister used to always draw spiderwebs in the corners of our school books with little spiders hanging off them. So the spiderweb thing took, and it was a way of trying to draw a connection between where I was and where the music from the first four Siouxsie and the Banshees albums had led me—how they had taken me on a journey to create some of the masterpieces that I’ve created as an artist.”

———

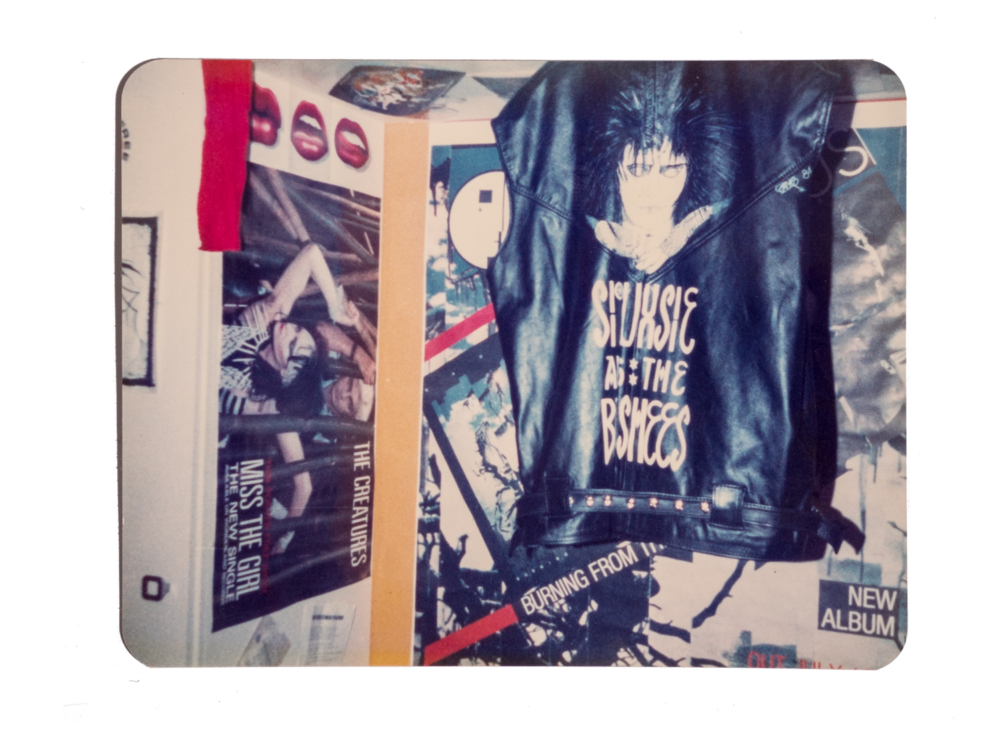

“I made this jacket. I put the studs on the back and painted that image of Siouxsie using leather dye. It was my pride and joy, my armor plating that I put on when I went to the gigs. Even at that age, I would make my own clothes. It’s the thing that defines you, because you aren’t afraid to step out of your front door wearing something that you’ve made. It’s very rare to see that these days. It takes guts.”

———

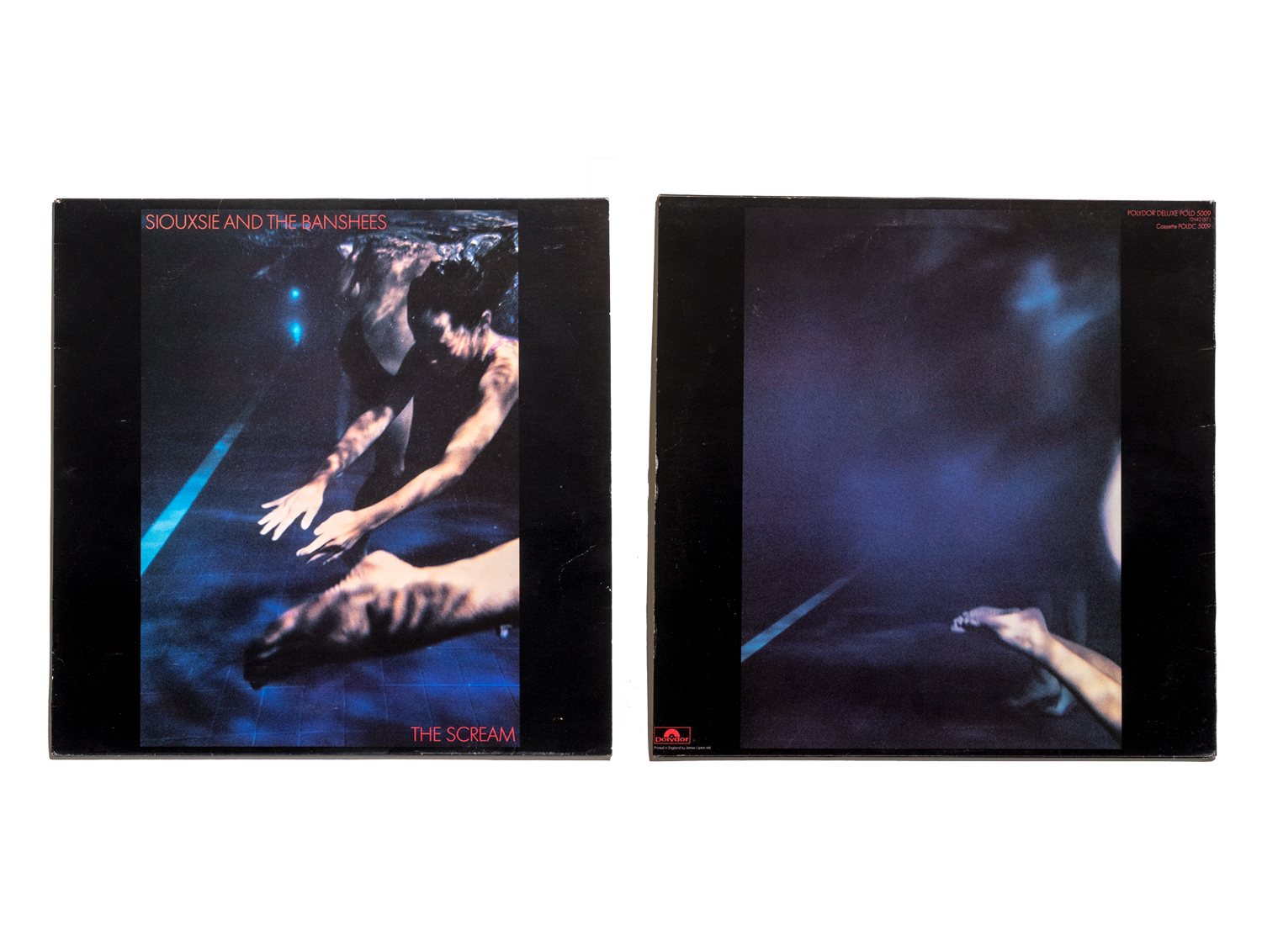

“When The Scream first came out in 1978, it felt like it was punk. But when you listened to it, it was almost like a soundtrack to a film. It wasn’t shouty and screamy. It was strong and powerful. It left a lot more to the imagination, so you could listen to it and be a lot more in the atmosphere of the music. And it’s such a good title.”

———

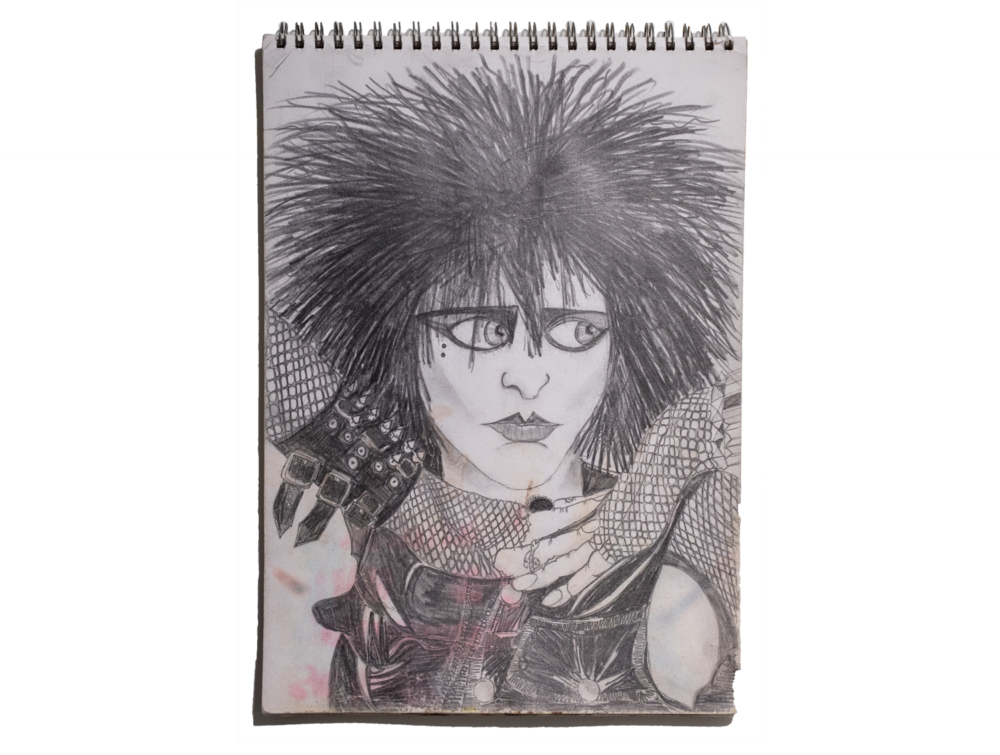

“My sketchbooks date back to something like 1984, when I was in school and leaning toward art college. I’d constantly sketch Siouxsie. I guess it was an obsession. It was the thing that pulled me through my adolescence. Growing up in a suburban town called Leicester, I felt like an outsider. When I first saw an image of Siouxsie, I realized that I felt so different than the world into which I’d been born. I didn’t have friends that had similar tastes. I was drawn to the dark side of life. It was powerful to see images of women who weren’t afraid to be outspoken, who didn’t conform. They wanted to be listened to and had something to say. To an 11-year-old girl growing up on the outskirts of town, that was a wake-up call.”

———

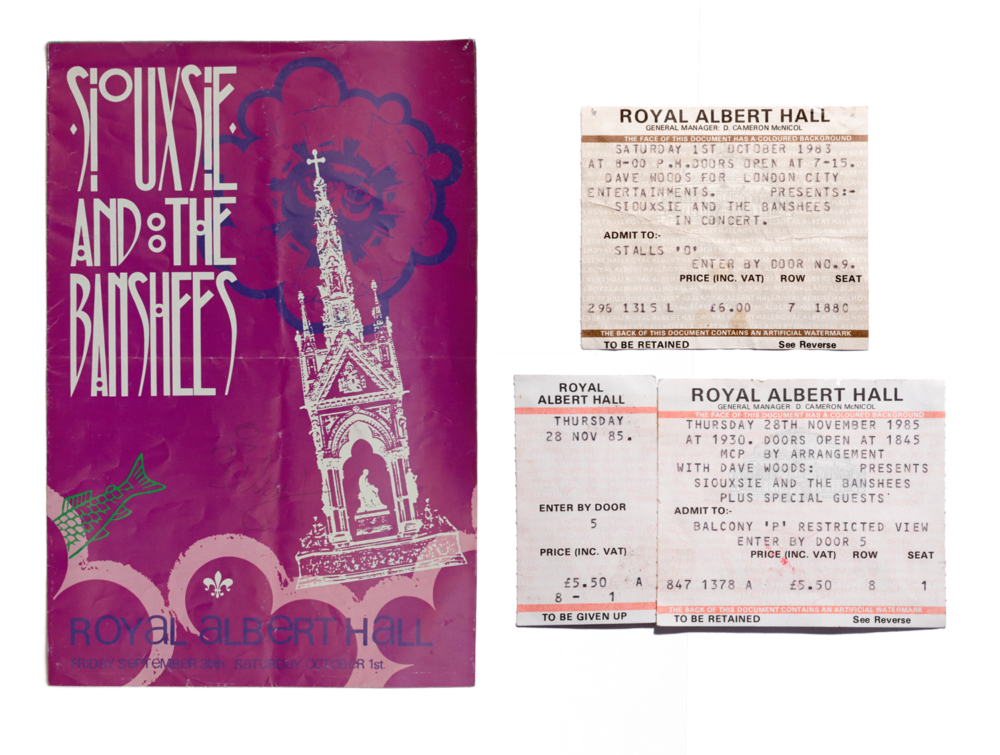

“The first time I saw Siouxsie live was in 1983. I had a boyfriend who came with me, and he’d shaved his hair off into a giant mohican because he was trying to impress me. We were queuing up with our tickets to go in, outside the Royal Albert Hall, with all of these other people in leather jackets and striped hair. Just queues and queues of punks trying to get in. But The Royal Albert Hall is traditionally a classical music venue, or it was back then, and the people at the door were the same people who would be monitoring a classical music performance. They were old ladies wearing long velvet dresses. I will never forget the contrast. It was such a beautiful thing.”

———

“This is possibly worth quite a lot of money. Some fashion label would probably reproduce it in this state, and make a fortune from it. I bought it when I was a teenager, and we used to customize our own t-shirts, so we cut the sleeves off. This thing is holding itself together for dear life with safety pins. But even though it’s on its last legs, covered in sweat and blood and tears from every concert I’ve been to, I can’t bear to throw it out.”

———

“We used to turn up at school wearing these giant badges. We’d get them free with magazines. Smash Hits used to have, as an incentive to buy the magazine, a badge hooked to the front of it. They were famous for having free badges on the cover. But as punk, or the music scene, got more refined, badges got smaller and they became the one-inch badge—the pin badge. We used to put them on our school uniforms. I remember turning up to my religious studies class wearing an ‘Anarchy in the U.K.’ pin. I thought I was so cool. My teacher came up to me and asked, ‘Do you know what anarchy means?’ Of course I didn’t.”

———

“The Crime Scene is a three-dimensional version of the spider graphs. I put a photograph of myself in the center from when I was 11 years old, around the time I discovered Siouxsie and the Banshees. I had to lock myself in a room to try to solve the mystery of my own history. I had all of this stuff from my teenage years that was in these cardboard boxes that my father had packed away. They were stuffed full of letters and records and old t-shirts and concert tickets. I just started pinning them all on the wall and then joining them together with string. I was trying to unravel my brain and the mystery of who I am, and what made me into the person I am today. In many ways, it’s a self-portrait.”

This article appears in the Winter 2019 issue of Interview magazine. Subscribe here.