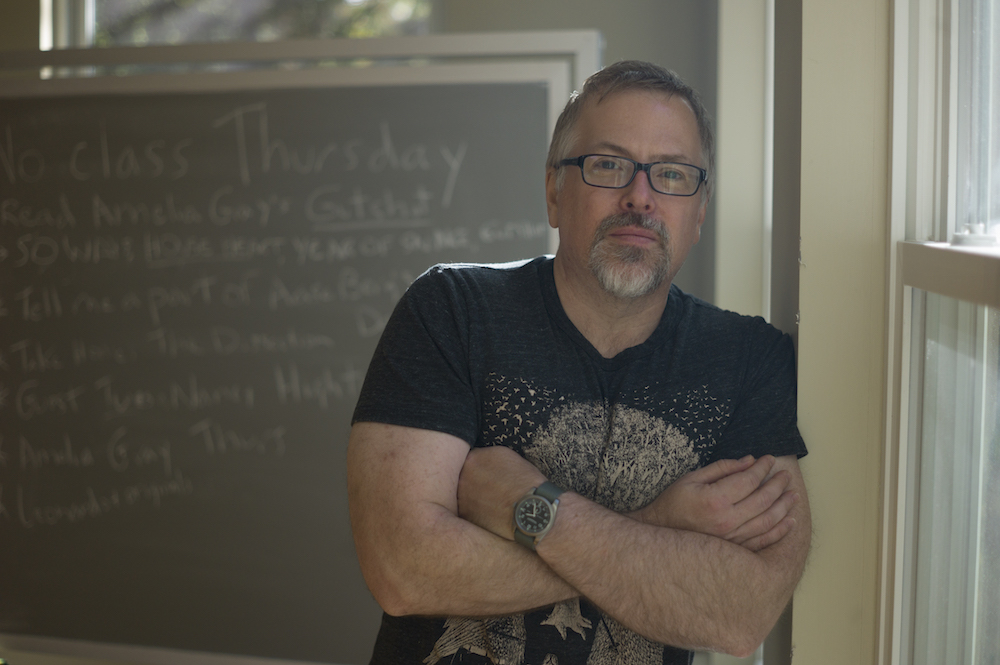

Annihilation author Jeff VanderMeer talks to TV chef Alton Brown about science and storytelling

IMAGE COURTESY OF PARAMOUNT PICTURES

Jeff VanderMeer is the breakout sci-fi author of this decade. His wildly popular Southern Reach trilogy—Annihilation, Authority, and Acceptance, all published in 2014—brought mainstream audiences into his baroque world of horror and intrigue, where malicious fungi and mutated beasts roam free in an enclosure called Area X on the Florida coast.

VanderMeer’s hallucinatory imagery coupled with his understanding of biology and physics gives the trilogy a cortex-gripping depth. Rarely in fiction has such drama occurred beneath the lens of a microscope. VanderMeer grapples with climate change and the failure of bureaucracies without preachiness, all the while illustrating the gorgeous complexity of organic systems.

VanderMeer followed up the trilogy with this 2017 novel Borne, a post-apocalyptic parable about a girl, her shape-shifting sidekick, and a giant flying bear. Last week, the film adaptation of Annihilation, directed by Alex Garland (Ex Machina) and starring Oscar Isaac and Natalie Portman, came out in theaters nationwide. The film caps off a stunning decade of accomplishment for the author.

A few weeks ago, he spoke over the phone for two hours with his friend and fellow science-adjacent talent: Alton Brown, the brainy chef behind the influential Food Network show Good Eats (1999-2012) as well as a former host of Iron Chef America and current host of Cutthroat Kitchen. Despite their divergent fields, the pair share a common interest in what Brown describes as inspiring a “level of curiosity” in audiences that will “push [them] into learning and discovering more.”

ALTON BROWN: You and I both mine the fields of science, but neither one of us could actually be called scientists. Do you find that you’re constantly having to push yourself to understand enough science to be seen as serious in your work?

JEFF VANDERMEER: There are two things going on. One is doing a lot of research into things like animal behavior, but then also knowing—in areas like physics—that any crazy thing I come up with is likely to be validated by some theoretical physicist the next week. When I was working on Area X it was like, “Is this going to be too out there?” Then I read some articles and decided, “No, this isn’t out there enough!”

BROWN: When you’re researching, are you inspired more by what you find as you wander through things, or are you looking for justification for what you already want to write?

VANDERMEER: What I’ve learned over the years is [how] to know the difference of what’s going to work and not. Sometimes the research is necessary beforehand and sometimes it just gets in the way of the writing—it answers questions that the reader doesn’t care about. The animal behavior stuff is really important to get right, because so many writers get it wrong.

BROWN: Why do you feel that getting things right matters?

VANDERMEER: An important reason that we’re in the trouble we are in with climate change is that we don’t have a handle on our environment. We form public policy based on information that is wrong. I want to create an atmosphere in which there’s a lower amount of bullshit. If you were to put together a recipe, can you just throw things together with this idea in your head that they’re going to work, and it works out most of the time?

BROWN: I think that’s doable but it doesn’t work for me. I consider myself a storyteller, I just happen to use recipes, which I actually refer to as applications or proofs. My thing is kind of like the old Talking Heads lyric: “Facts all come with a point of view / Facts don’t do what I want them to.” I’m not concerned with the perfection of factual transference of information, I’m interested in concepts that make people go, “Oh! Okay, I am no longer going to look at an egg the same way again.” People are reading your work now and becoming involved in larger issues. There have to be scientists saying, “What the hell, this guy doesn’t know what he’s talking about and people are looking at him like he’s a prophet!” But you know how to communicate.

VANDERMEER: I have actually had science departments and science conferences bring me in just to talk about the storytelling in The Southern Reach trilogy, because they feel the frustration of not being able to communicate their findings. If the scientists can’t communicate in a sense that you can then turn their findings into actual public policy, that’s where things begin to break down, and why, again, we’re in this situation we’re in.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY KYLE CASSIDY

BROWN: Is there a chance that the science community’s inability to communicate to the non-scientific world is part of why we are where we are?

VANDERMEER: Not really, and I’ll tell you why, because they’re supposed to do their job. They should never have been placed in a position where they have to do this.

BROWN: Well, whose job is it then?

VANDERMEER: In a logical, functioning society, I think this information gets carried across to politicians and everyone else who needs it, in such a way that it creates public policy that’s devoid of radicalized ideologies, that’s just for the common good.

BROWN: When you talk about the effects of storytelling, I would argue that it was a lack of storytelling finesse on the part of the Obama administration that has led us to where we are right now. If the storytelling and communication had been handled better, there would not have been the massive swing of the political pendulum that happened with the election of our current president.

VANDERMEER: I definitely think that’s a factor, but I also think Obama was under attack from the very first day he took office, and I think he had to spend a lot of his time and attention being reactive. Seeing how easy it’s been for Trump to reverse a lot of the environmental stuff has been depressing and instructional at the same time. There simply aren’t enough constitutional safeguards in place to protect against a rogue president. So I don’t know what the answer is. I was teaching at a college in upstate New York when the election occurred and I know that a lot of the professors were stunned at how many of their students voted for Trump, and had no prior idea that they were planning on doing that.

BROWN: I think young people sometimes just want to revolt.

VANDERMEER: Yeah. And it was revolting.

BROWN: I had a friend who had read the Southern Reach trilogy who referred to it as the first feminist science fiction book she’d ever read. And I asked her why, and she said, “Women are in control of every situation.”

VANDERMEER: It has to do with my own work experience. I used to work for a succession of software editing companies that would have contracts with state and federal agencies. And I would be the documenter of meetings, sometimes doing limited business analysis. I began to become quite cynical about how the world works. It works on ineptitude and inefficiency, and a kind of passiveness. I get that that’s disconcerting for some readers. I had a certain number of male readers say things like, “Why doesn’t she just make up and reconcile with her husband, I don’t get it.” It’s been quite interesting to see how just tweaking what we expect in terms of power dynamics and gender can create all kinds of different responses.

BROWN: As I look back at the trilogy, the book that made me the most uncomfortable was Authority. I found the inner workings of the Southern Reach far more disturbing than Area X. As you’re writing these two worlds, are you saying that ultimately our minds are not societally outfitted to deal with nature?

VANDERMEER: Our brains are not really set up for thinking in the long term yet. That’s an evolutionary stage that we manage, but it doesn’t come naturally to us. And unfortunately, we have to keep thinking longer and longer term, the more complex our societies and countries get. There are a lot of human-created systems that we like to tout as being logical that are actually riddled with illogic. And then on the other hand we have all these natural systems that are not conscious, but they are logical and they work really well. My main point is not that we can’t get there, it’s just that we don’t. We think of a smartphone as being, well, smart, and we think of the plants outside as being dumb, even though they may have networks between them and communication elements that, if we were to adapt some of what we learned there, would make our own systems more logical.

BROWN: Have you seen a cut of [the film] Annihilation?

VANDERMEER: I’ve seen a rough cut, yes.

BROWN: And?

VANDERMEER: Well, I can tell you how my body felt. My body was sore all over afterwards because it was so tense. I would say it falls in the horror/sci-fi genre more so than the book. [The director] Alex Garland himself has said this; it’s a loose translation. There are trade-offs. My reaction, though, was that I was on the set and saw some of the scenes being filmed, I’d written the book, I’ve seen all this fan art, so there are all these overlays in my head. My body appreciated the movie, but my conscious mind was thrown out throughout the entire movie, because of those other things that were coming in and spoiling it for me.

BROWN: In your writing, you purposely make decisions, in your descriptions of things, that can lead a reader into a very challenging and uncomfortable place.

VANDERMEER: J.G. Ballard is the writer I studied the most as a teenager. Not the substance of the stories, but the way that he expands and contracts space and time. In Annihilation I had this idea that throughout the expedition they’re always going down—even when they’re described as going up into the lighthouse, they’re actually going down. I deliberately destabilized those descriptions so that there are words that actually apply more to going down than going up. Subconsciously, it’s supposed to give you a little more vertigo.

BROWN: People talk about the time that you grew up in Fiji. How much of you, the writer, was formed by your years in that paradise?

VANDERMEER: Pretty much all of it, in a way. Just the proximity to the natural world and being able to live in it. There was also this other weird juxtaposition that went into making me a writer. I had terrible allergies to some of the blossoming trees. I had asthma. I had this weird juxtaposition of being in this beautiful place and feeling miserable half of the time.

BROWN: Does nature ever scare you?

VANDERMEER: Every once in a while when I hike by myself. There’s the St. Mark’s Wildlife Refuge in Florida with a shit ton of wild boar. I don’t care about alligators, I don’t care about anything else, but wild boar are unpredictable. That used to scare the crap out of me, the anticipation of coming across a pig.

BROWN: They can be terrifying. I’ve seen wild pigs in South Georgia. You and I are neighbors, we’re both Southern; unless you’ve seen one, your brain can’t wrap around it really well. I’ve told people, imagine a small Fiat, now cover it in fur and give it tusks. Because people are like, “Oh, pig,” and I’m like no, you don’t understand what I’m talking about.

Can we just talk about Mord [the giant flying bear character from the novel Borne] for just a minute please? First off, I almost named one of my cats Mord. I was going to, right up until the moment he got inside a wok, and he became Stir Fry.

VANDERMEER: That’s so cute.

BROWN: Who the hell invents a five-story-tall flying bear? You have to understand that on a certain level, that shit’s funny.

VANDERMEER: It is. [laughs] That’s why you’ve got to really commit to it. There can be no irony to Mord because irony will make him fall.

BROWN: Walk me through the sequence of creating Mord.

VANDERMEER: To walk you through Mord, I have to briefly walk you through how the novel came to me. I had this vision in my head of this sea anemone-like creature that was buried in very dirty seaweed and this woman was reaching out toward it, and a lot of things happened at once in my head. I realized she was reaching toward it because it reminded her of where she had grown up. I realized the thing in question was actually potentially intelligent. And I realized it wasn’t in seaweed, it was embedded in the dirty flank of a giant bear.

BROWN: Okay, okay, okay. So describe to me the mushrooms you had eaten half an hour before this came to you.

VANDERMEER: You know, I get so many people who ask me if I do mushrooms and I just tell them I don’t, and they’re so disappointed. In fact, we sometimes get mushrooms from fans to the P.O. box which I have to immediately get rid of. [laughs]

BROWN: But I mean, normal people don’t just all of a sudden say, “Oh, and then I realized the seaweed was the fur on a giant bear!” Bullshit, Jeff. Nobody thinks that way.

VANDERMEER: [Laughs] Well, when you do it in that tone of voice, it sounds ridiculous! But it got worse, because then the bear flew off. And I had to think to myself, am I going to keep the bear or not?

BROWN: Is Mord mindless?

VANDERMEER: No, I don’t think Mord is mindless. I think Mord had become more mindless as he’s bought into his own myth, so to speak. I wanted him to be like a hurricane, something that was exacted upon the city randomly. I wanted him to be the thing that appears on the horizon and changed your life forever.

BROWN: Was Borne, for you, a palate cleanser? Because Borne was actually—gosh, it’s hopeful, it’s funny, it’s loving, it’s terrifying, yes, it’s weird, but I find it comforting.

VANDERMEER: Yeah, it was a palate cleanser. How can I write about these immense, terrible things but still show that life goes on, that people still joke in extreme situations, people still take care of each other? I think it’s really important to show that. Otherwise, you get this grim, right-wing militia wasteland view of the future that isn’t really accurate. No matter what the future is, it’s still going to be complex, right? It’s still going to have all the things we know now, just in a different form. I think in that book, humor becomes an expression of love and hope. It’s a precious resource.

JEFF VANDERMEER’S LATEST NOVEL THE STRANGE BIRD (FARRAR, STRAUS, AND GIROUX) COMES OUT FEBRUARY 27, 2018.