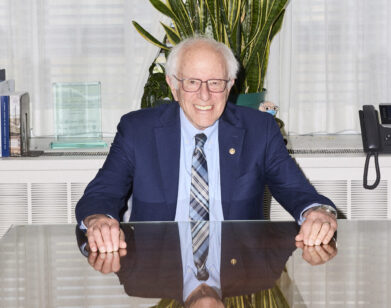

A.M. Homes’ Family Affairs

In the recent New York Times review of A.M. Homes’s latest novel, May We Be Forgiven (Viking), critic Garth Risk Hallsberg described the author’s style as minimalism (specifically the literary minimalism that, according to Hallsberg, was in vogue in 1990 when her breakout short story collection, The Safety of Objects, was published). But I prefer to think of Homes’s style as “maximalism by other means.” The 50-year-old writer does not build characters or plots with oozing, gaudy adjectives or melodramatic trajectories. There’s a cool, controlled tenor to her sentences, so extraordinarily lucid while painting such extraordinary disasters, that the presence of a detail-obsessed watchmaker is clearly evident behind the lines that build her stories. The results are worlds with dimensions heaped upon on dimensions heaped upon dimensions (and particularly for Homes, that hi-def treatment has often been reserved for the suburbs, as in her frightening1999 novel Music for Torching).

May We Be Forgiven is perhaps her biggest, broadest, most spacious novel yet, a dark carnival of American life in the 21st century, and she doesn’t bother with a slow simmer. In just the first 30 pages, a TV executive named George Silver kills almost an entire family in a car accident that seemed less accidental than heat-seeking, and then murders his wife, who happens to be in bed with George’s older brother Harold. Harry, a flailing Richard Nixon scholar and holder of a lifelong grudge against his younger brother’s successes and excesses, is forced to sort out George Silver’s life, children, pets, business, attachments, and prison sentences as he takes up residence in his modern house in the New York City’s suburbs. Homes allows her novel to take detours—private school upstate, trips to the mall, a family vacation to colonial Williamsburg, a laser-tag sex night for suburban couples—but the plot never wanders away.

Since the start of her career, Homes has been barraged with a slew of foreboding synonyms when critics describe her fiction—haunting, terrifying, twisted, dangerous, dark (and its refined brother, darkly comic), bizarre. (Even I did it above, with “frightening.”) But what gets me—what has gotten me ever since I read The Safety of Objects in my own suburbs as a teenager—is that Homes’ writing is probably the most realistic depictions of American life that we can find in literary fiction. The travesties and tragedies she records seem the stuff that make up most lives below the skin and aluminum siding. Homes is ultimately a realist, which is why those adjectives placed on her work reveal a strange disconnection we have with our own lives or how literature is thought to reflect us.

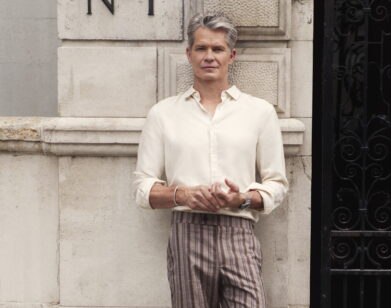

She answered a few of my questions when she returned to the city from her month-long book tour in America.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: The genesis of May We Be Forgiven was a short story. Does this often happen to you—getting an urge to build onto something that’s supposed to be a limited, contained piece of fiction?

A.M. HOMES: No, it really doesn’t happen often. And worse yet, I am philosophically opposed to short stories that become novels. But this is the second time it’s “happened” to me. The first was Music For Torching, and, in both Music and May We Be Forgiven, very significant events happen about 30 pages into the novel. Right at the moment that should have ended the story I found myself charging forward despite it all, which creates a kind of problem. You have to up the ante with regard to the drama or the story engine. May We Be Forgiven started as a story that Zadie Smith asked me to write for her anthology, The Book Of Other People (2008), the idea of the story being to focus on two characters. I started writing and just never stopped. The book took many years, and even then I was six months late turning it in. I’d likely still be writing if the editor would have allowed it.

BOLLEN: You’ve frequently explored the theme of sibling rivalry—from your 1990 short story “A Real Doll” to the recent story in The New Yorker, “Brother on Sunday.” What I love about the tension between Harry and George Silver is the irony of the fact that those whom we most resent or dislike so often are the very ones whose lives we’re forced to take charge of in moments of tragedy. What draws you to the family?

HOMES: What draws me to family… if I were a psychiatrist, I’d say an enormous amount of unresolved personal material. If I were an anthropologist, I’d say families are at the root of social structures—they shape our identity, our belief systems—and so I find them fascinating. Also, I love the idea that families have narratives that are essentially the family story that is passed along generation to generation—and the rifts start when people question the story.

BOLLEN: Do you think families everywhere are loaded with open rage and misunderstanding? Or is that an American specialty?

HOMES: Not really, but I’d say our ability to supersize those emotions are American-made special effects. In European countries, people mostly stay close to home and whatever rage there is simmers under the surface—it’s what made the plays of Shakespeare and Harold Pinter so good.

BOLLEN: What I love about your writing is the way your characters come across as less these overly defined types—blonde hair, blue shirt, chipped tooth, age 41—but more these menacing and moving vortexes of frustration, desire, anger, confusion, doubt. I tend to think writers have styles because that’s how they write—that’s how the words fall together—but a “Homesian” character is a particular kind of literary creation. How do you envision your characters as you move them through a story? Are you inside them, or are you watching them from high overhead?

HOMES: I like to think the characters unfold, or reveal themselves organically. Grace Paley, who was my mentor, always talked about writing the “truth according to the character,” and I take that pretty literally. I check what I’m thinking against what I know of a character’s background, history, emotional life, etc… My characters are heavily layered, which I think is hard for some readers—i.e.. they’re not good or bad or just after one thing. To me they’re very real and very human, which means complex and flawed.

BOLLEN: I think a lot of writers need to get out of their own way when they draw a character. They have to stop themselves from piling on every description at once (look at this highly original character!). Yours seem to build beautifully from vapor to liquid to solid. When you started writing, what details attracted you to a character?

HOMES: That’s good question, and something I talk about a lot with my students. I think one has to select details very carefully—and they should be reflective of the character’s interests or through the character’s eyes. A good example is that perhaps someone wrestling with a drinking problem would constantly notice what others are drinking and how much. Someone who is on top of the world would be noticing other things. Whatever details are used should be like scaffolding that supports what we’re learning about the characters.

BOLLEN: As you mentioned, in May We Be Forgiven, the most shocking events happen in the first 30 pages—murders, a car accident. The book refuses to follow the programmatic arc of a typical novel. Instead, you open the story up, allowing new characters in late, following detours, letting events move and shift around the characters. I’m sure May We Be Forgiven would drive a traditionalist crazy, but I wondered if this freedom has something to do with your writing for television in recent years—this idea of an open-ended episodic narrative as opposed to the 19th—century novel structure.

HOMES: The truth is, I think of myself as a very traditional writer in terms of structure. That being said, I didn’t know that you couldn’t bring someone new in late in the book. I also really don’t watch enough TV to know about the impact. In my experience as a TV writer, I would say is the exact opposite—it’s very constricted, all having to conform to a form. My sense of fiction writing is not to think about rules but to be driven by the characters and their stories. I often ask myself what’s at risk here, who needs what, and how are they going to get it. There has to be a reason for the reader to stop living their own life and start reading your book.

BOLLEN: Harry Silver is a Richard Nixon scholar. The character (and thus the author) knows his Nixon history/biography quite well. What kind of research did you do into Nixon? And should there be Nixon studies seminars in liberal-arts colleges?

HOMES: There’s no need for Nixon Studies as a course in and of itself, but I do think we need a better education in world history and importantly going forward, economic history. For the book, I read an enormous amount by and about Nixon, both books written long ago and those more current. I especially enjoyed volumes by his psychiatrist and his physician, though I’m not sure how they justified writing them. Talk about privacy violations. There’s an enormous amount written about Nixon and his presidency. I also visited the Nixon Library, which is also his birthplace in Yorba Linda, California, and found that very exciting. You can request special files, etc., and go through the documents in person. It’s amazing. The Nixon Library website is also quite wonderful.

BOLLEN: Not only that, you actually write short fiction stories attributed to Nixon in the novel. How did you come up with Nixon’s particular writing style and subject matter? I love that he writes these very quietly twisted average-Joe American stories.

HOMES: I thought a lot about Nixon’s personal history and the changes in America during his lifetime and tried to craft stories, which I thought reflected some of his personal history but also the backdrop of a changing America. Nixon grew up in a strict Quaker family. The idea of the American Dream, of hard work and not much fun, was ingrained in Nixon as a child, but curiously so was a love of music. Nixon himself was a pretty good piano player. So it’s the contradictions that interest me, as I think we all have them.

BOLLEN: Earlier I mentioned detours in the novel. One in May We Be Forgiven is to Colonial Williamsburg. When I was little, there were always commercials on in the morning before school from the Colonial Williamsburg tourist board. I always wanted to go. Did you actually go?

HOMES: I took a trip to Colonial Williamsburg as part of my research for the book—I’m big on research. I’d gone as a kid and wanted to go back and see if it was anything like what I remembered. We had a great time—but the town itself, old Williamsburg is only a few blocks long. The cool thing is that you can book a reservation to stay overnight in one of the old colonial houses.

BOLLEN: I know some die-hard A.M. fans out there. Have you ever had a strange fan encounter? Can literary fiction fans ever be fanatical?

HOMES: I’ve been asked to sign various bits and pieces of peoples’ bodies and I politely decline. And sometimes people come up at a reading and whisper that they think we have “something in common,” which usually refers to some kind of sexual predilection—that we do not have in common. It means a lot to me that people read the books. But the fact is I’m really shy and prefer to communicate through the books rather than one-to-one in the flesh, so to speak.

BOLLEN: I think one of the reasons that your work really holds people is that you write such brutally honest stories, but also there is room for a sense of compassion. The title of the novel itself asks for compassion. As you have gotten older—and had your own child—has the morality or ethics of your stories changed? Or is that a ridiculous assumption and the part of you that is a writer is a separate entity from the personal A.M. Homes around her family?

HOMES: I’m very interested in compassion—compassion for oneself and others. I write about very complicated characters and experiences and try to do it without judging the character or the action. That said, I think there’s a very moral core to my work. And yes there is a separation between A.M. Homes and A.M. Homes—the human A.M. is much crankier around the house than the brilliant A.M. Homes, who is, of course, always compassionate, generous, and good humored.

BOLLEN: I’d love to hear a little bit about your memories of the literary world when you first started out. Did you find any sort of tribe of fellow writers in the literary community?

HOMES: Ahh, the golden years when books were still printed on paper. When I was first starting out, there were a bunch of us who used to go to the Cedar Tavern—yes, the same place that Pollock and de Kooning went. It was Jonathan Franzen, Philip Gourevitch, Rick Moody, and a few others—including David Foster Wallace and Jeff Eugenides when they would come through town. Most of us had day jobs in publishing—it was a good time. There was hope. The idea that one might make a living as a writer was alive. We had aspirations of having lasting and supportive relationships with book editors like the infamous William Maxwell and Maxwell Perkins. What’s amazing is how much publishing has changed in the last 20 years. I rarely meet a student who aspires to become an editor, and the idea of making a living as a writer is fading fast. What’s worrisome is that an occupation that dates to the beginning of time—scribe—would somehow just evaporate during our lifetimes…

BOLLEN: I recently reread the 1996 Times review for End of Alice and had forgotten how harsh that review was on you. Did you expect that kind of reaction? Do reviews get to you?

HOMES: You really can’t write well if you’re thinking about what the reviewers might say. That said, the intense, negative reviews to End of Alice seemed personal, which I was surprised by, but on the other hand, it was clear the book had a big impact. I encouraged Scribner to use the negative reviews as a positive and take out an ad with all negative reviews on one side and positive on the other. Do reviews get to me? Yes, only in that often people writing reviews have no idea about the amount of work that goes into writing a book and that given the state of publishing, I’d like to quote Thumper from the film Bambi—perhaps if you don’t have something nice to say, then don’t say anything at all? I’ve always prided myself on being very forgiving re: negative reviews but recently had a good long talk with myself and asked why? Why, if Norman Mailer can pick fights, can’t I? So, I aspire to punching someone in the nose… I just have to work out the details re: what would happen next.

BOLLEN: May We Be Forgive starts—and ends—on Thanksgiving. What is your favorite holiday?

HOMES: I’m not really a holiday person. I find them stressful—too many people, family members with enormous expectations, food and travel. A recipe for disaster! I do like going uptown and watching the Thanksgiving floats get inflated on the night before Thanksgiving. That’s what I call the “good kind of melancholy.”

BOLLEN: Ultimately, the novel drives toward a new, contemporary definition of what a family is. The American suburbs used to be the setting for the traditional family unit. In May We Be Forgiven, the suburbs are no longer so traditional—there’s a lot of Internet sex, for one thing. Did you want to write a more hopeful view of the new American family?

HOMES: The struggle is how to write optimistically when the world we’re living in is not inherently optimistic. I love the idea of the family from the most Norman Rockwell version to Norman Bates. Without family, we have very little—it is the most basic social structure. So yes I suppose I wanted to write a hopeful book about the evolution of the family.

A.M. HOMES’ MAY WE BE FORGIVEN IS OUT NOW.