Drake Gets Cold Feet, and Other Stories from Twenty Years of Alife

From the original Alife store on Orchard St. All photos courtesy Alife.

For nearly two decades, the streetwear institution Alife has been synonymous with a certain Lower East Side aesthetic shaped by the convergence of late-90’s skate culture, graffiti, and hip-hop—the same ingredients that birthed a global movement so pervasive its influence can be seen from the Balenciaga runway to the suburban shopping mall. Well-documented in Alife history are its laundry list of major brand collaborations, from the obvious (Reebok, Adidas, Fila) to the left-field (Budweiser, Crocs..?), as well as the famous faces that have graced the shop’s backyard-turned-dais to perform records off their latest LPs. But long before Alife became a destination for in-the-know hypebeasts and Instagram-obsessed tourists alike, it was a no-frills commercial storefront between two fabric wholesalers on Orchard Street, housing a creative agency and a host of oddities from homemade ink to Foamposit clogs.

Of the four founding members, only Rob Cristofaro, a Bronx-born former graffiti artist, remains with the brand. A True Yorker of the white tee and Timberlands stripe, Rob is as proud of the scope of the brand’s influence as he is its spirit of defiance (exhibit A: their early-in-the-game decision to “kick out all the cronies from Nike” who’d descended upon the store, a move that ultimately lead to a collaboration with the brand). Despite a few rocky years, including some inner-turmoil and a few brushes with over-expansion that backfired, Alife has managed to retain its credibility—the most valuable currency a brand that aims to shape culture can have—as well as its lease on a rapidly gentrifying block. With the twenty-year mark approaching, Interview sat down with Cristofaro to take a look back at how the clubhouse inside 158 Rivington became a staple of downtown consciousness.

Three 6 Mafia at Alife in 2008.

———

“When we started Alife, before we opened, in the graffiti community I put the word that we were gonna start this space, which was gonna be a platform for anybody that wanted to do something that they had passion about, whether it was furniture, whether it was creating product, whether it was artwork, clothing, whatever it was. The initial meeting was all the boroughs, really anybody in the New York metro area, it was Brooklyn, it was Bronx, it was Queens. Then you had a lot of the kids that worked in the store that were skaters from New York. So little by little, we became this hub that had everybody.

In the early days, out of our space was born a [graffiti] crew called Irak. They were like Wu-Tang Clan, probably like 20 people. And from that crew were guys that really blew up to become the top contemporary artists of today—Ryan McGinley, Dan Colen, Dash Snow, Kunle Martins. We were the safe house for a lot of these kids that used to come and hang out. We would do parties, we put them in Mass Appeal. That was like a big emphasis, you know, putting focus on a lot of these young kids and giving them a place to kinda like, get shit out there.

Drake performing at Alife in 2013.

We had art shows on the regular. We would show guys like Ryan McGinness, Steve Powers, Todd James. We didn’t have corporate money. But we had art people—big art people—watching us, and not only art people, but brands also. Jeffrey Deitch would see what we were doing and would say, okay, I like this, this is new talent, and would come and basically poach the people that we were showing in our space. Nike would come and say, ‘Okay Steve Powers, we’re gonna give you a shoe, we’re gonna give you $100,000.’ Jeffrey Deitch would go, ‘Okay, here, you guys just did a show at Alife for a budget of two thousand dollars? I have a budget of $250,000.’ This is the kind of shit that was happening.

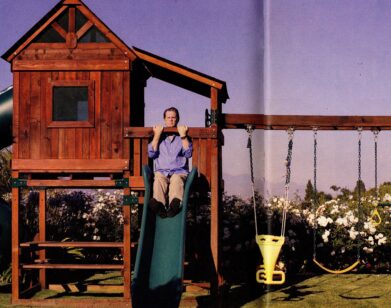

From the original Alife store on Orchard St.

John Mayer jamming at Alife in 2006.

When we lost our lease on Orchard Street in 2004, we moved to Rivington Street. We lost our ability to do these big visual exhibitions. What we did gain was a backyard. So it went from visual art to performance, you know, musicians and shit like that, and that became a whole ‘nother era. I had no clue who John Mayer was. He was introduced to me through an old school graffiti writer, John Matos, who used to write “Crash” years back. We originally were talking about working together on something, and John was like, ‘You should meet this guy John Mayer. Maybe do something incorporating music.’ So he came to my studio with his new CD and we popped it in and we listened at the table. My initial thoughts were that this isn’t really our audience, but I don’t give a fuck—you’re passionate, you’re doing your thing, we’re gonna give you the venue. Rather than just have a performance, we wanted to do something new with the music. So we mixed these two guys together—Just Blaze, who comes from our scene, and John Mayer. We wanted to let them organically create. Here’s the stage, here’s the platform. Here’s a small audience. For the first one, we had like 60 people come. Didn’t really publicize it. John Mayer came with like, six fucking guitars. Just Blaze came, got his shit set up. They shook hands, they talked for five minutes before, Just Blaze started playing his shit, John Mayer just sat down, and fucking, boom, they free-styled a session.

That was the initial concept—having people be in kind of an uncomfortable situation, where a lot of them are used to performing in front of a lot of people and shit, but our venue is different. Our venue is very small, very personable, you’re performing right here, you’re rubbing arms with people. Drake’s first session at Alife—it took him fucking 45 minutes to gather enough confidence to get on the mic. And then by the second one, you know, you got Raekwon, you got Travis Scott climbing on the walls and shit, before he was anybody. That’s where him and Drake met. Then when Nas was here, he was just doing a record release with us, not really trying to perform, until he was fucking sipping and smoking and was like, fuck this, gimme the mic. The performances we get in this little venue… we’ve had sessions that aren’t relevant, you know, we’ve had fucking Biz Markie DJ’ing and Doug E Fresh MC’ing. And you know what they turned the session into? A fucking dance party. Biz Markie was playing house music, Doug E Fresh was getting people hyped up and dancing. It’s a weird venue. You never know what the fuck is going to happen.”