The Last Interview With Robert Morris

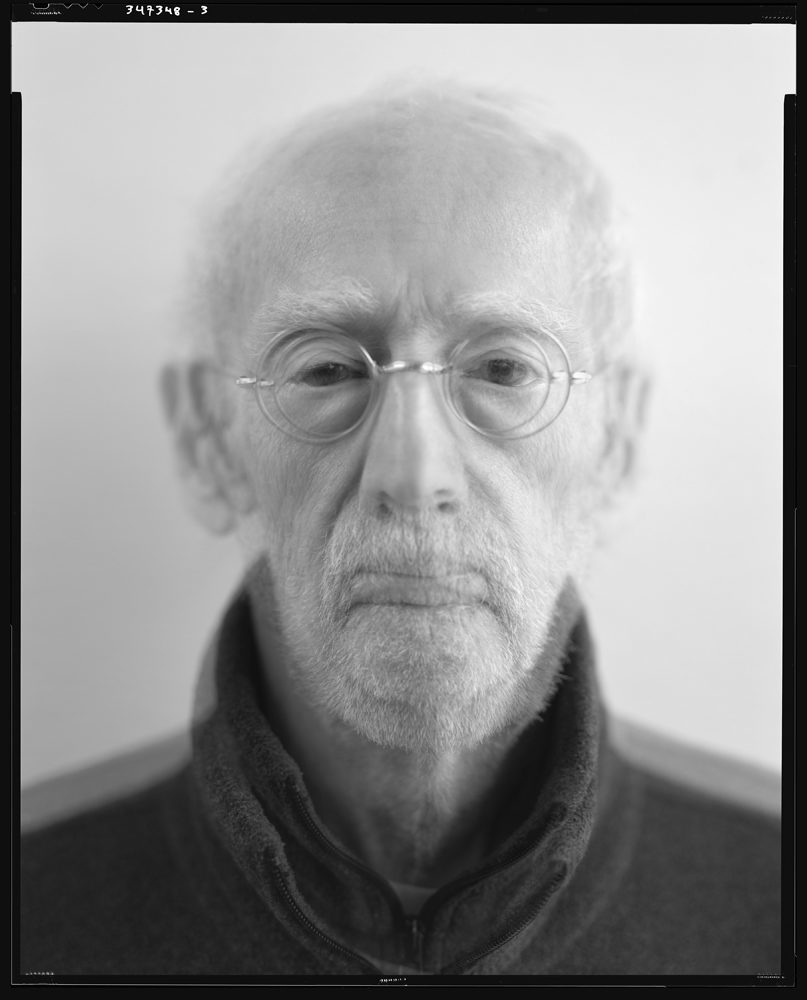

Robert Morris by Grant Delin for Interview Magazine (2014)

Attempting to interview Robert Morris runs the risk of receiving Unavailable, a 2011 letter written by the artist listing the reasons why he is unable to accommodate the request. He elucidates thusly: “I do not want to be interviewed by curators, critics, art directors, theorists, aestheticians, aesthetes, professors, collectors, gallerists, culture mavens, journalists, or art historians about my influences, favorite artists, despised artists, past artists, current artists, future artists.”

Rarely, though, Morris will make an exception. This past spring, over the course of two days, the artist best known for his Minimalist sculpture and performance work with the Judson Dance Theater shared the story of his life’s work for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. More than once, Morris clarified that this would be his “last interview ever.” It was a gentle threat made real with news of Morris’s death, this week, at the age of 87. During the second day, as he discussed an infamous pair of homoerotic posters, the result of a bet between him and Lynda Benglis (“I do not want to talk about posters I should never have made”), Morris motioned to pause the tape recorder, a twinkle in his eye, and walked off. Five minutes later, he returned with print out of Unavailable and sat down for an amused reading of his text.

When asked about Judson Dance Theater, the early 1960s art and dance movement that convened at Greenwich Village’s Judson Memorial Church, Morris lit up as he shared a stream of stories about performing with the women of the collective: Yvonne Rainer, Carolee Schneemann, Lucinda Childs, and Simone Forti, to whom he was married from 1955 to 1962. Each artist is central to the ongoing MoMA retrospective, The Work Is Never Done, showcasing the collective’s performances, photography, and sculpture. Of all the artists covered during our conversations, Morris spoke of each woman with an impressed glow—a drastic contrast from his mild-to-hostile remarks about the more-famous (and categorically male) artists he is regularly tied to: Dan Flavin, Robert Rauschenberg, and Donald Judd.

What follows is a sparsely edited, and largely uninterrupted, oral history of Morris’s monumental experiences as an artist during New York City’s explosively creative post-war years. Radical, controversial, and simple, Morris laid a foundation for new approaches to dance and performance. He dismantled tired conventions of artistic discourse, opting for the expansiveness of letting the work ask every question. As he wrote in Unavailable: “I am happy to be just material for somebody else, so long as I can exercise my right to remain silent.”

———

On Box with the Sound of Its Own Making and Column

At Anna Halprin’s, I met La Monte Young, the musician, and I got to know him pretty well before he moved to New York. So when I came to New York, I knew La Monte and John Cage. Simone and I had a fifth-floor walk-up on Amsterdam Avenue. I called up John Cage and I said, “I have something I think you might like.” He came over, walked up these five flights, and I put the box with its sound on the table, turned it on for a couple of minutes, and said, “This is a box with a sound.” He said, “Don’t turn it off.” So I turned it back on, and he sat for three and a half hours—didn’t move—listening to it. Then he got up and left. Nobody’s ever listened to it for three and a half hours, except Cage.

That was in January of 1961 that I made the Box with the Sound of Its Own Making. At the same time, I made the Column out of plywood. Down on Bond Street, Simone, Yvonne Rainer, and I shared a studio. Next to the open space where Simone and Yvonne improvised and rehearsed, I had a little room with seven-foot ceilings. I couldn’t stand the column up because it was eight feet tall. I made the two things at the same time: the box, the column. In those cramped quarters, something happened.

On War with Robert Hewitt and La Monte Young

I knew Simone and Yvonne and some of the dancers. I knew a painter by the name of Robert Hewitt, who was at Hunter. We were always taunting each other. I remember walking down Sixth Avenue with him one day when I said something he didn’t like, and he picked me up and threw me on top of a car. I mean, the guy was so strong.

I choreographed this work called War with Hewitt. We were talking about war, and the problems of not having a war in this country, when we need an enemy. So we decided to do this confrontation. We both made our suits of armor. It only lasted a few minutes in the basement of Judson. I had made a big gong that Mark di Suvero cut out with a welding torch at his studio down on the fish market. It sort of popped up into this kind of beautiful curve and I made a frame. La Monte played the gong, just hit it, while we were doing War. Afterwards, I gave it to La Monte, and he put microphones around the edge and bowed it. He made music with the thing.

I didn’t have any money then and Simone and I had broke up. I was quite impossible to live with, I know, and I don’t blame her for leaving. It was a very depressing time for me. Anyway, La Monte knew Yoko Ono, and she had this loft on Chambers Street, and she let me work and live in it for a winter. There was no heat and no hot water, but I lived there and made work.

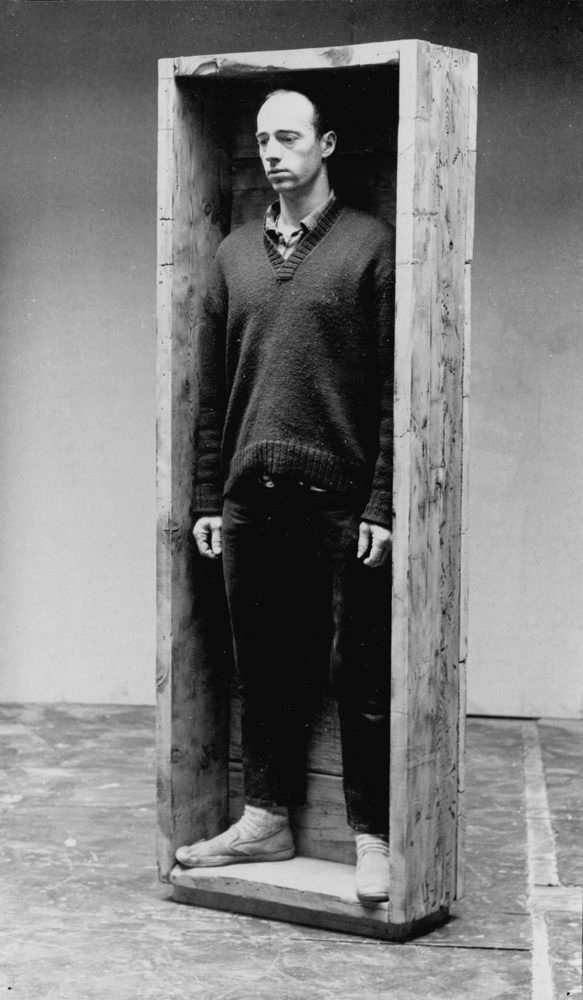

UNTITLED (BOX FOR STANDING), 1961. COURTESY OF SONNABEND GALLERY, NEW YORK.

Evenings at Yoko Ono’s Spare Loft

Jackson Mac Low gave a reading. Simone did her famous Dance Constructions. Henry Flynt gave a lecture. I’ll never forget this. He stood up and said, “Before I give this lecture, I have this Jew’s harp.” He put it on the table and he said, “We’re going to have a contest, and whoever thinks of a game first gets to play this Jew’s harp.” Simone immediately said, “This is the contest, and I win.” Henry said, “I’ve been out-reasoned.”

I made the props for some of Simone’s performances like the inclined plane and the box. One thing she did was come out and get under this box and make sounds. After a while, you forgot there was a body there. It was a strange transformation.

When the time for my evening came, I made the Passageway. You came up to the door of the loft, and there was just this passageway. You couldn’t see in the loft. You couldn’t go in there. People wrote little messages on the wall, like “Fuck you, Bob Morris.” Things like that.

I made sculpture in that loft, plywood pieces, mostly, that one winter. Yoko didn’t do anything there, but she let us use the loft. She liked to be around famous people. When Shusaku Arakawa arrived from Japan and became Yoko’s boyfriend, I had to move out.

Sculpture

I was in a group show in 1961 or 1962 at a little gallery on Fifth Avenue, around Tenth Street, called Gordon’s Fifth Avenue Gallery. The other participants were Japanese. [Shusaku] Arakawa was one. The theme of the show was boxes, and I had Box with the Sound, Column, and one of my slabs. Everybody had a loft downtown, so we rented a truck, loaded up the stuff, and went up to Gordon’s Fifth Avenue Gallery. It turned out that my slab was just a few inches too large in one of its dimensions to go up the stairway. There was a kind of clerestory window right at the floor level of the gallery in front. We decided to slip it through that window, and we all got underneath it and started lifting it up and pushing it into this narrow opening. Then it started to slip, and everyone started screaming in Japanese, and I couldn’t control what was going on. It slipped down, and it broke the gallery’s neon sign at the bar. But anyway, we got it in. I don’t remember the reaction of the show. It was very crowded. When the show ended, the slab had to come out the same way, and it slipped and broke the sign again—after it had been repaired. So the gallery was stuck with two bills for neon signs. That was the first time I showed in New York.

After that I showed with Richard Bellamy on 57th Street at the Green Gallery: a group show in the beginning, and then I had a one-man show after that in [December] 1964. Someone had pulled out of the show that was to open then, and I said, “Well, I’ll take that slot,” not knowing what I was going to do. Through November, I made all of the pieces that went into the plywood show of 1964. There was a corner beam that spanned a doorway. There was the corner triangular piece that fit in a corner. There was a slab that hung, I believe, from the ceiling, at eye level. A piece that ran against the wall, and a long 24-foot-long bench, and then a large piece that was nicknamed “the boiler.” It was around four feet in diameter by eight feet, and then it had two square ends. That was the plywood show.

“I think the fact that my work was about the body, that there was nothing there, took a while to sink in.”

It was noticeable and got some press. In those days, Donald Judd was writing reviews for Arts Magazine, and the reviews usually consisted of about 10 or 15 lines of description, and then, at the end, there was a judgement, like, “That’s third rate” or “That’s fourth rate.” That was typical of Judd. He said, “The problem with Morris’s work is there’s not enough to see.” I knew I was on the right track because those plywood pieces were more for the body than for vision. They were more haptic. They had to do with a sense of the body’s presence, and their presence against the body.

We were grouped together for some time, Judd and Morris and Flavin. I certainly didn’t have anything in common with their specific objects, which seemed to me to be really decorative objects. I have a lot more interest in Flavin’s early pieces, the white pieces, like Monument for Tatlin and things like that, because he used the space and the light, and they were ready-made. I thought it was much more radical than what Judd was doing. Later, Flavin got into colored neon and got very pretty. But yes, the beginning, because we were all at the Green Gallery, we got lumped together. It took a while to live that down.

I think the fact that my work was about the body, that there was nothing there, took a while to sink in. I remember I had a floor slab in a group show at Green. I called John Cage, and I said, “I have this show. Maybe you’d be interested in seeing it.” He went to see it with Jasper Johns, who I was getting to know then, and who later told me what Cage had said: “I went to see Morris’s work, but I didn’t see it. All I saw was this slab.” I thought that was wonderful, a reaction like that from someone like Cage. When I went to the gallery, Bellamy said, “You know, Philip Johnson was here, and he went in there and he saw your slab, and he came into my office and he said, ‘I’d like to have a broom to kill it.’”

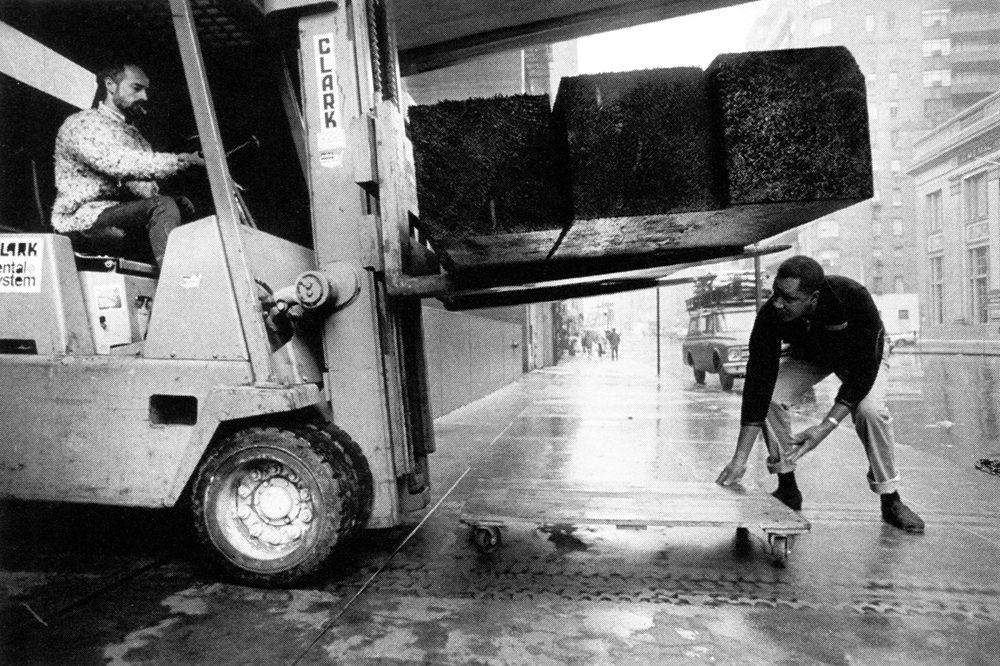

MORRIS OPERATING FORKLIFT. PHOTO: GIANFRANCO GORGONI/CONTACT PRESS IMAGES.

Judson Dance Theater

“Avant-garde” dance in New York at that time was Merce Cunningham. But what was he doing? He was doing ballet according to the I Ching. He just mixed up the movements, but it’s still ballet. It’s still partnering. It’s still all of the conventions of dance, which I detest. Most of the people who performed at Judson were studying with Cunningham. Trained bodies, all that nonsense. But not entirely.

Carolee Schneemann approached me and said, “Maybe we should improvise and do something.” We met in the gym of Judson. She took off her clothes and started painting herself. I didn’t think this was something I could deal with. It was too distracting. We met again and the same thing happened. Finally, I said, “Carolee, I don’t think we can just do this as a kind of collaboration. One of us has to direct. I’ll direct the first one, and then you direct the second thing, and we’ll perform in each other’s work.” She agreed. So we did Site.

Site started in the dark with a blackout, and I’m standing with my back to the audience upstage. Next to me there was a white box, under which an old Wollensak tape recorder played the sound of a rock drill that I’d recorded out the window of my loft on Sixth Avenue, where they were tearing up the street. Then the light comes up, and I walk over, and on the right side of the board, I put my left foot against the bottom of the horizontal sheet of plywood, and reach to the top of it, and pull it, and so it pivots up. Then I walk that board to the back, and lean it there. All of this is rather slow. Then I walk back again and do the same thing to the second board. I walk offstage with that and pause. Then I come back, take up the third board, and there’s Carolee behind it. I put the board, against the second one, which I use to move around with. I spin it one way, and then the other way. I drop it on the floor, walk onto it, get the corner and pull it up—then I back off of it. Then I reach down at the two edges, pull it up, and at one point I throw it up in the air and catch it and balance the 4’ x 8’ sheet, which is not so easy. The board was my partner, in a way, in this piece—and I have a mask of my own face. I do certain gestures with a mask, take off a glove, trace the edge of the plywood. All of it’s slow, except there are these moments when physical exertion comes in and moves the board in some way that requires a little bit of balance and strength.

Yvonne Rainer did these interesting group pieces that involved a lot of people moving around props like mattresses. I performed in those. Rauschenberg did something with a great big parachute or whatever, on roller skates and turtles on the floor. Rauschenberg was somebody I could not really relate to. He once told me, “You know what your performance is like?” I think he was talking about Site. I said, “No, what?” He said, “It’s like giving someone a saltine without salt and saying, ‘How do you like that?’”

Then I did Waterman Switch with Yvonne Rainer. It was two figures, nude, face to face, on two tracks that I made, which we inched down to very lush music from the opera Simon Boccanegra. There was the first movement. There was a second movement: I was running in a circle around the second dancer, Lucinda Childs, who was dressed in a suit as a man. There was another section where the two nudes stood on stones, I think, and balanced at the back, and I lifted a stone with a Muybridge slide, doing the same thing. Then the last movement was Yvonne and I going the other way.

Lucinda used different kinds of cloths that sort of harked back to Martha Graham. But it was very different. There was something spectacular about just looking at Yvonne. She had such a presence that anything she did was totally riveting. That was the last piece I choreographed. I got so much static about using nudity that I sort of soured on the whole thing. People were saying, “Oh, this is just some kind of sensational spectacle.” And maybe it was. But I think there was something about the choreography, about the performances, that involved a kind of bodily imagery and movement that sculpture suppressed. I felt a need for that, and I could find it in the dance. It was very satisfying for a while, and then I somehow passed out of it. I can’t say why. I don’t know why. It just ended. I said, “I’m finished. I’m going back to sculpture.”

There’s a show coming up in France where they want to redo the Judson performances, but I don’t think I want to do it. For me, they’re over with. They’re finished. They don’t exist anymore.

———

Adapted from an oral history interview with Robert Morris, 2018 April 19–20. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.