Sarah Lucas tells Matthew Barney about the joys of wreaking havoc with her art

This past May, in Toms River, New Jersey, Sarah Lucas torched a 2006 Jaguar. The 55-year-old British artist had already cut the car, which she bought from a salvage yard in Brooklyn, in half with a rotating saw. She stuffed the back half with hay and set it a blaze. The front portion of the Jaguar met a different fate. In the Long Island City studio of her old friend, the artist Matthew Barney, Lucas glued Marlboro Reds onto its entire shell. She has been working with cars since the late 1990s, and this burnt-and-smoked rendition will be one of the centerpieces of Au Naturel, Lucas’s September retrospective at New York’s New Museum. The show also includes many of the found-object sculptures that first brought her fame in the early ’90s as part of the notorious Young British Artists, a loosely connected group of friends and collaborators who wreaked havoc on the era’s self-serious sensibilities. While Lucas was in New York working on the new exhibit, she took time out to talk to her friend and temporary studio mate about cigarettes, turning hate into humor, and getting the car without the corpses.

———

MATTHEW BARNEY: Could you ever make a work about something you truly disdain?

SARAH LUCAS: I once covered the front door of my house in pizza leaflets. It was getting right on my tits, finding a bunch of them every day on my doormat. I don’t even eat pizza. It shocked a lot of people on the street, because it was impossible to miss. Other people were amused, especially kids. The leaflet delivery guys didn’t know what to make of it. I saw them hesitating to come down the garden path. Some people were even scared. Security-wise, it’s a great advantage to live in a scary-looking house. To answer your question, it’s difficult to keep up disdain once you start engaging. It’s more a case of turning it around and sending it back out. It was similar to when I started using tabloid newspapers years ago: I had great disdain for them and for the world that was reflected in their pages. Once I started using them in a work, I’d be thinking, “Oh, that’s a good headline,” or, “That’s a good spread.” It certainly required a sense of humor. Would you say that you engage in things you disdain? I would think the opposite, that you’re doing exactly what you love to do, very extravagantly.

BARNEY: No, not disdain. But I do need to find things to work with that put pressure on me and my sensibility. Combining subjects that I don’t necessarily like with forms and characters that I’m fond of tends to work well for me. It creates conflict in the work, and I need that.

LUCAS: I remember you once saying that you felt a need to be more embarrassed by what you’re doing, that embarrassment is the gauge of whether you’re really onto something.

BARNEY: I think you and I had that conversation when I was craving more of that vulnerability. It was at the beginning of the “River of Fundament” project [2014], when I had started performing some of the narrative in live situations. That live work was raw and embarrassing at times, but it was definitely what I needed. Why did you choose a Jaguar sedan as the focus of your new work for this exhibition in New York?

LUCAS: I went looking around old car-breaking lots in New York one snowy day with Sadie [Coles, the owner of the art gallery Sadie Coles HQ] and Miciah [Hussey, a director at Gladstone Gallery]. I was on the lookout for something quite wrecked. The thing is, I’d recently acquired a seriously wrecked car in Mexico. It was something I’d fancied getting my hands on for years. They’re difficult to obtain in Europe—and probably in America—because they’re caught up in the bureaucracy of insurance and court cases and all the machinery for ensuring that vehicles are accounted for at all times and properly disposed of. I’d previously asked Mexican friends about the possibility of getting one, and they said, “Sure, you can get one with the dead bodies still in it if you like.” So that’s what I did—without the dead bodies. It was so mangled you would hardly believe it, like something that had dropped out of the sky. So when I was looking around New York on that day for a car for this show, I wasn’t impressed with the stuff we were looking at. Then Anthony, the car-lot bloke, said he had another lot around the corner, and we trooped ’round there and there was the Jaguar. Sadie found it quite glamorous.

BARNEY: Why did you choose to cut it in half?

LUCAS: The New Museum wanted a car piece, so Massimiliano [Gioni, the museum’s artistic director] asked if I would consider making or remaking one of the cars. Then it turned out that none of them would fit in the lift of the museum anyway. So I said, “Don’t worry, we can cut it in half.”

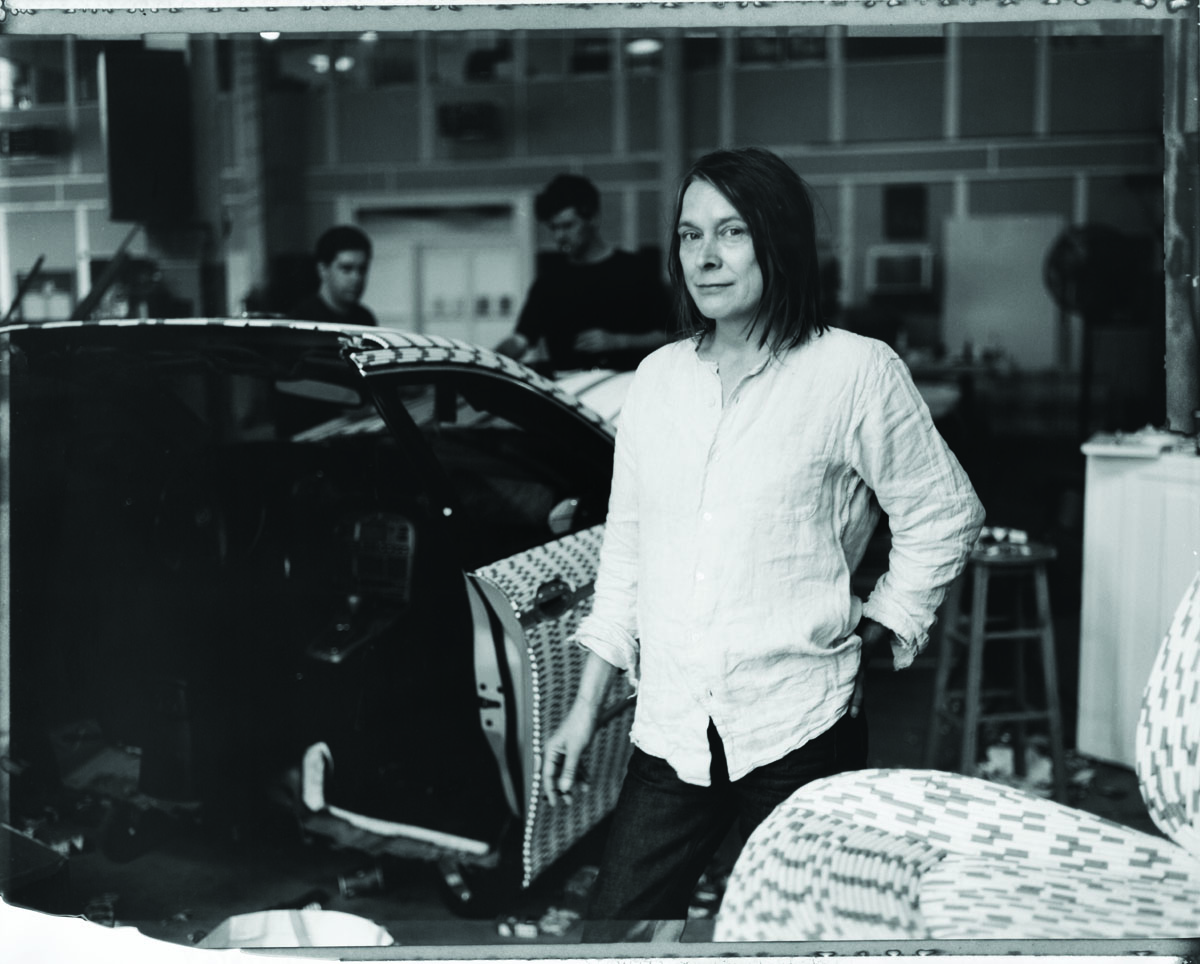

Lucas borrowed her friend Matthew Barney’s studio in Long Island City, Queens, to produce her most recent work for the show.

BARNEY: Have you ever started with a car that was in such good condition?

LUCAS: I don’t think I’ve ever started with a viable car, although a couple of them did still drive a bit. One time, in London, a Ford Capri I had lined up was a tiny bit too wide to get into the exhibition space. A friend of mine, Alan Kane, said, “Don’t worry, we’ll get it in.” He got in the driver’s seat, put his foot down, and rammed it through.

BARNEY: The cars in your work have operated so differently from piece to piece. In some works, there is a kind of desecration to the car, particularly where the transformation is subtler. In other works, the car is more of a stage, or mise en scène. Sometimes it’s more formal, like a pedestal. More recently, the cars feel like characters with a broader range, emotionally and formally. The piece you made in Mexico [“EPITAPH BLAH BLAH” (2018), which featured a wrecked car covered in cigarettes] was very beautiful in that way. It was in equal parts violent and exquisite, traumatized and regal. Some of your past works with cars have had an irreverence about them. This new piece doesn’t feel that way to me.

“I once covered the front door of my house in pizza leaflets. It was getting right on my tits, finding a bunch of them every day on my doormat. I don’t even eat pizza.” —Sarah Lucas

LUCAS: Funny you should put it that way. As we got more and more into the job, an atmosphere was created that was almost like that of a church. Anyone needing to come through the gallery sort of tiptoed, and that became a very emotional and moving thing. How key is your working relationship with people? Is it more important than the end result?

BARNEY: So much of what I do is done with a group of people. The film productions are obviously collaborative, but so is the sculptural work and all the material experimentation leading up to it. So those working relationships are key for sure, and many of them go back a long way. On a basic level, the work is about the relationship between things more so than the things themselves. And that definitely includes the collective experiences and bonds that were formed in the process of making the work.

LUCAS: I’ve noticed, visiting your house, that you’re not very concerned with the trappings of the art world: having a nice house or a well-displayed art collection or any chi-chi stuff that people reward themselves with and pump themselves up with. Your parties, when you have them, tend to have the spirit of a bunch of cowboys ’round a campfire.

BARNEY: That’s funny. I’m always hoping that something will happen in a social situation; maybe the mosh pit days destroyed my ability to sit passively and enjoy something. I like that kind of community purging. When we have parties in the studio, there usually ends up being a physical event at the center of it. We made a huge slide out of all the plastic offcuts for a Christmas party one year. You were at the one more recently where we made a bucking bull from a miscast part of a sculpture, suspended from some rope. In a situation like that, it’s true that people tend to stand in a circle around the object. It’s maybe more of a ritual than a party, but it’s fun. The way you throw eggs at the wall at some of your exhibitions feels that way to me—that it might be a collective purging as much as it is an art-making decision.

LUCAS: I conceived of that as an event for women, given that men get to spill plenty of seed already. For an exercise in futility, it’s surprisingly elevating. In Mexico, I relaxed the rule a bit because I’m not actually a sexist and I could see the men were dying to throw eggs, especially the boys. So I said they could have a go if they dressed as women. It was sweet.

BARNEY: How much are your decisions influenced by the place where you make work?

LUCAS: I don’t tend to have a plan about how a show will be before I get to the place in question. I like to be as open as possible about the hang. Actually, I see the hang as an artwork in itself. Also, I generally make some things in the situation—sometimes everything. So the influence of the place, people, what’s available, whether I have to rethink things because of that, is absolutely real and present. And it usually moves my own ideas forward in unexpected ways. Do you leave much to chance? Of course chance always happens, but I can see you being very determined to get what you want.

Lucas used between 50 to 55 cartons of Marlboro Reds in affixing cigarettes to the shell of the dismembered 2006 Jaguar.

BARNEY: It depends. There are certain scenes in the filmed or performed pieces, or sculptural works, that are designed to be uncontrollable. In those situations I’m more interested in reacting to what is happening and in having the opportunity to improvise through the process. It’s especially exciting for me if I’m forced to react quickly. In general, I’m slow to decide, so I need to find ways of tricking myself into making a more spontaneous choice. But as far as installation goes, I guess it’s true that I tend to draw out a plan ahead of time and stick to it. Can you talk about the layout of cigarettes on the car in Mexico?

LUCAS: I guess you’re wondering if there is any particular significance to the patterns. I expect if you were doing it, there would be. There was no prior plan about how the patterns should be. It’s dictated to a great extent by the shape of each section. Working inwards, decisions have to be made: how to get around an obstacle or to flow into the next section. Also, things get tighter moving in. Often a decision is called for, and that will have consequences for the pattern. It’s more revelation than design.

BARNEY: I remember a number of years ago you gave me a bar towel that had the flag of England, Saint George’s cross, on it. It was around the time you were working on a project focused on an English footballer, Charlie George. I liked to use the towel, but it always felt loaded in a way that I couldn’t totally understand as an American. Eventually, I wondered to what extent that project was about letting red into your work, by way of the cross of Saint George and the jersey of Charlie George—the same way that yellow became so central to your installation in Venice at the British Pavilion.

LUCAS: For Venice, I wanted to do something architectural. I had the idea that a breeze block and MDF [medium-density fiberboard] floor throughout would be great. But then I thought about the logistics of it, and started to realize that it would probably turn out to be an absolute nightmare. Meanwhile, I’d been musing over how to get eggs into the show. My working premise was “MAKE A SARAH LUCAS SHOW.” A Sarah Lucas show needs an egg in it somewhere. So between this notion of stepping over the threshold of the pavilion into a total otherworld on the one hand, and trying to do something about eggs on the other, arose, like a lightbulb going on in my mind, the color yellow. And really that was the key to the whole thing. The plaster “Muses” I was working on became meringues in a sea of custard. What could be more uplifting, I thought, than a dessert? I had a drink and a cigar at that point.