art n craft

Code-Switching in Art and Craft: Sanford Biggers in Conversation with Diedrick Brackens

Sanford Biggers. Photo by Giancarlo Valentine.

“I don’t think these are going to be really, totally understood until someone unearths them decades down the line,” the artist Sanford Biggers says, discussing his quilt-based tapestries, paintings, and sculptures, currently on view as part of his exhibition, Codeswitch, at the Bronx Museum. History is important to Biggers; to grasp the meaning of his art, he explains, it’s necessary for viewers to recognize the network of individuals that have formed his materials and method.

Biggers began incorporating antique quilts into his practice ten years ago, inspired, in part, by the alleged importance of quilts in the Underground Railroad. Some historians believe that nineteenth-century abolitionists would stitch coded messages into quilts and hang them from laundry lines, guiding escaping slaves to safety in the North. Quilts, Biggers reminds us, function as metaphors, too; by virtue of their patchwork, they build upon the generations before them, as all cultural forms do. Works throughout Codeswitch make reference to hip-hop, funk, and jazz music, in particular—passions of the artist, who heads the “multimedia concept band” Moon Medecin. A QR code linking to a Moon Medicin performance appears on one quilt, a sequin disco ball glitters on another, and, as with all three musical genres, they are rife with sampling and improvisation. The works on view also pay homage to the myriad of Black American artists whose practices have engaged the history and mythology surrounding the African Diaspora. The art historian Kellie Jones, whose book South of Pico examines the community of Black artists that rose to prominence in L.A. in the 1960s and ’70s, situates Biggers as an “heir” to those practitioners, building upon their work to expand their discourse.

Before traveling back to L.A. for the first time since the pandemic, Biggers sat down (virtually) with the emerging textile artist Diedrick Brackens, who knows a thing or two about the art of craft. Since the artist’s first institutional solo show at the New Museum last year, Brackens has gained considerable recognition for his vibrant allegorical weavings investigating Black and queer identity in America. Below, the two artists reflect on the significance of “code-switching” in their respective practices, the legacy of South of Pico in present-day L.A., and the indelible influence of Missy Elliot. —ELLA HUZENIS

Diedrick Brackens. Photo by Alex Hodor Lee.

———

SANFORD BIGGERS: I am trying to figure out travel from the East Coast to the West Coast, which I haven’t done yet. Have you traveled yet?

DIEDRICK BRACKENS: I’m in Texas. I live in Los Angeles, but I drove out. Everyone’s like, “It’s fine to fly,” and I just was like, I want the space, the time, the assurance that I can take my own precautions and stuff.

BIGGERS: My parents are actually from Texas, so I used to spend a lot of time there as a kid. My dad was from Galveston, and my mom was from Houston. They met in junior high school. I’m sure are aware of John T. Biggers.

BRACKENS: I did some research and found out that you’re maybe tangentially related.

BIGGERS: You know how it is. We cousins and brothers. My parents were friends with him and Hazel [Biggers]. I grew up knowing him and met him several times, even showed him my art once when I was in high school. We kept in conversation and would check in for many years.

BRACKENS: How did you find your way into art?

BIGGERS: I actually think John might have had something to do with that, in addition to growing up with prints and artworks that are now considered Black Romantic work, like images of Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, of course. Beyond that was Barbara Wesson and Varnette Honeywood and Elizabeth Catlett, Charles White. I grew up with that around my house, and all my parents’ friends’ homes had that too.

I actually was going more towards music at a younger age. I took lessons for a little bit but got bored with it and then started playing by ear. My older brother had garage bands, so I would play along with the band and had a little garage band of my own in junior high school and high school. Then I got to a point where I started listening to jazz, and I couldn’t play what I was hearing by ear, so I started painting and drawing the musicians. Then that led to drawing civil rights [leaders] and some more obscure historical figures at that time. When I would show them and share them with my friends, they’d often ask, “Who were these people?” It was a good source of information exchange and education. How about yourself?

BRACKENS: I think I was always drawing and writing and had a good deal of support. Not necessarily that people were like, “We get it and we’re pushing you this way or that,” but they gave me the freedom to figure it out. So when I hear this idea of being enmeshed in this world of art, I’m like, “Oh, wow, that sounds amazing to think of people around who get it and can pivot you.”

BIGGERS: Well, I don’t know if they necessarily got it, but they did appreciate the idea that art was something that was supposed to be part of your existence. That was big, because a lot of people don’t have that. When I was locking myself in my room and drawing and painting, my mom was really skeptical, but my father actually was supportive. I was all over the place as a kid and having problems in school, and art was one thing that I would calm down and really focus on. I started getting some recognition as a high schooler. The teachers would ask me to put my works through the hallways and stuff like that. So they were like, “Just see where this goes. He’s going to apply to college. He’ll figure his stuff out. Let’s see where this goes in the meantime.” Did you have to stake your claim as an artist to become the Artist?

BRACKENS: There was some claim-staking, for sure. I didn’t really start seriously making art until high school. And then, when I went to undergrad here in Texas, I decided to study art there. It’s weird to be home talking about this because my mom’s standing in the kitchen.

BIGGERS: I love it. Hey Mom, what’s happening?

BRACKENS: My recollection of it was that my parents were nervous. I had decided I was going to study English and biology, and then the first day of classes I dropped all of the bio and signed up for whatever art classes were being offered. My dad was like, “Okay, yes, I’m supporting it.” But behind the scenes apparently, he was freaking out, and my mom was the one who was like, “It’s going to be fine.” But I never witnessed any of this. As I started to have shows and things, they were always there.

Sanford Biggers, Bonsai, 2016. Antique quilt, textile, paint, tar. Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Sanford Biggers. Photo credit: Object Studies.

BIGGERS: I think that’s one thing that’s great about where we are now. There’s enough of us out there in the world where it doesn’t seem crazy to think of becoming an artist. When I was growing up, no peers were doing it.

BRACKENS: Yes. I remember in the beginning, thinking, “I have to do this because there’s not a road map.” It’s exciting to think that maybe I get to be one of the last generations of this idea that there’s no one to look at for how to achieve this, because there’s so many folks in the ecosystem right now. I don’t have to be a “possibility” model, or the next person doesn’t have to be one. So the show [Codeswitch] is up? I’m assuming you’ve been?

BIGGERS: I went, and I was very active in the installation. On some level, I think it’s the ideal viewing experience, because people who go in are going there because they want to go. And once they’re there, they’ve got the whole run of the place with very little competition, very little outside distraction. On a pure viewing level as an artist, and as an artist wanting to really get into the work, I think it’s great. I do miss the fact that we couldn’t do the whole vanity project of big openings and the visibility-type of thing. But I guess everything has a time and place, right?

BRACKENS: Absolutely. It’s interesting. I get something out of watching people engage, and getting to talk to them about the work. That, I think right now, is the thing that is most sought after. But when you were talking about the “vanity” part of it—I don’t think I really committed to what that meant until now, when there’s only five people there and you’re like, “I mean, does it exist? Did it happen? Am I important?”

BIGGERS: Of course, that’s the thing. It’s a tangibility that you can’t cross-reference by the reaction of the people. How are you dealing with exhibiting?

BRACKENS: I had a show up in L.A., and we had a small opening timed throughout the day. It was really amazing, both to be able to talk to everyone who wanted to engage and be able to not feel “ping-pongy.” It was surreal to see the emotional impact of folks getting to see art after months and months. A lot of people seemed really overwhelmed in a positive way from the experience. And I think, to some degree, the materiality of the work, this thing that you think about touching, brought people to life a little bit.

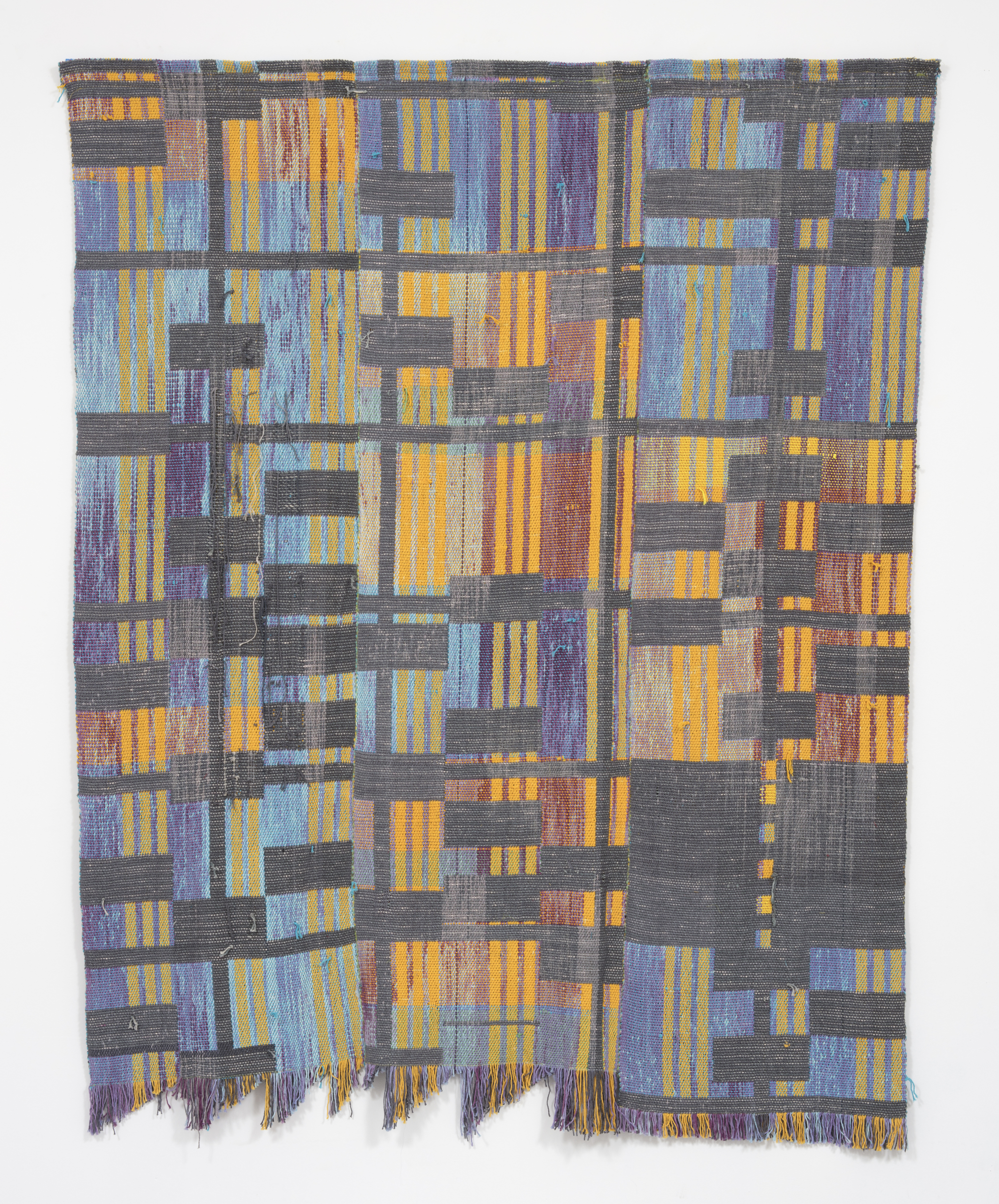

Diedrick Brackens, wading still (bend, bow, pull), 2018. Woven cotton. Courtesy of the artist.

BIGGERS: I was in a conversation earlier today about how to figure out a schedule be able to enjoy the show with some other people in person. Because the few times I’ve gone to the show after it’s opened, that exact same thing has happened. People are just looking at your work, and they don’t know you’re the artist. I love watching that. But because it’s so small, somehow they figure it out, and you end up having these really interesting exchanges with people. How long does it take you to make your work? I know you get asked this all the time, but I have to know, because you have a lot of work, and it’s all varied, and I can just imagine the hours…

BRACKENS: I would say roughly about a month from conception to all the processing—dying the material, weaving it, sewing it. What about you?

BIGGERS: They range. After working on them for the last ten years or so… I go through different periods where I try different approaches to making them. Sometimes it’s thought out, and I’m going to plan this imagery or try to make this imagery occur within this pattern or within these parameters. Then, I might go through a phase where I’m like, “I’m going to go in there cold. I’m going to grab a brush or spray paint or a handful of tar. I’m going to throw it on there and just respond.” The most recent phase has been actually cutting and pulling away fabric and creating a void. It takes a long time because there’s only so much room for a mistake. Fabric has a mind of its own, so you have to do various preparations to make it respond to your cuts and to affect the way it’s going to hang. It’s process-oriented, for sure.

Sanford Biggers, Quilt 14 (Flying Lotus), 2012. Embroidery, fabric treated acrylic, spray paint, cotton. Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Sanford Biggers. Photograph by Object Studies.

BRACKENS: What is the reception to you as a Black man who’s making this work?

BIGGERS: I definitely expected a pushback because there’s a perception of working with this type of material as a gendered thing. I’m using those materials and paying deference to that, but at the same time, I’m an interloper, in a way. I ended up getting another pushback from quilters, hardcore quilters. But over the years, a lot of quilters have come over because they’re pushing boundaries in that genre. I’ve become friends with a lot of young quilters. We reach out. We’re in each other’s DMs. They come to lectures and shows. I point people in their direction. These are people who are not even claiming to be part of the contemporary art world, but just straight-up-and-down quilters. It’s gratifying. Weird relationships happen because of the material, because of the nostalgia and Americana and community aspect of some of these quilts and how they’re made.

I did a lecture in North Carolina once. This older white woman drove in two hours. She waited until after the lecture, came up to me with a bag full of quilt materials from her neighbor who was deceased and was like, “She gave them to me and I didn’t know what to do with them. I’m a quilter, but I’m not going to use this stuff. I know what you’re doing, and I think she would want you to have it, and I’m giving these to you.” I was so touched. Those strange things happen. That gives me more energy to go through the work. How about yourself?

BRACKENS: I think it’s a similar tightrope. I think a lot of my most productive conversations have been in these places and spaces where I know that I’m speaking this old white woman’s language, but I’m embedding this other thing that she would not otherwise have a way to consider. Or I’m using the material or the techniques to introduce her to my world or give her a through-line in ways that I’ve been like, “Oh, this is working. They hear me.”

The pushback has been minimal, but I came to craft before I came to art in some ways. I decided to leave behind parts of craft because I knew I was breaking rules and was fully going to continue to do so. I think textile folks are just arriving at this place where they have decided that they can part with some of the historical ideas that are embedded in the medium, which I’m so excited about.

BIGGERS: I totally agree with you. Even in the other bodies of work that I do that are not quilt-based, I’ve always been very interested and engaged in that notion of “craft” and “fine art,” and the high-low read. That to me is very, very fertile ground for expression, but also social evolution. I do feel like some of the craft community is looking outside of that realm. The “fine art” realm is also having to reinvestigate their notions and their biases as to what’s called “craft.” We’re dealing with vernacular culture. It only makes sense that we are translating things that were communicated to us materially and then putting it back out transformed, but also for other people to be informed by it.

Diedrick Brackens, blessed are the mosquitoes, 2020. Woven cotton and acrylic yarn, sewing notions. Courtesy of the artist.

BRACKENS: That makes me think about the title of the show, Codeswitch. I’m wondering if you could talk about code-switching and where you’re positioning the title of the show relative to the cultural things that I know are under there.

BIGGERS: Either I have ten answers for that, or I have no answer for that. I only say that because I like the fact that Codeswitch can embody so many different interpretations. I like the idea of the materials code-switching. I like the temporal nature. Some of these materials are antique, but then you have me working on them. I don’t really think these are going to be really totally understood until someone unearths them decades down the line and they’re seeing the through-line from the multiple people who’ve intervened on these materials. I think there’s that code-switch between craft and fine art that we spoke about. The power in softness, I think that’s a code-switch. The high-low. There’s just so many. You’re dealing with a lot of code-switching in your work thematically. How do you see that idea of code-switching?

BRACKENS: For sure. I do think that things get flipped and reversed.

BIGGERS: Did you just quote Missy Elliott?

BRACKENS: See? I knew you would get it. I like the idea of not being on stable ground. I know that there are certain associations that people are going to find immediately. I like finding this way to get them to reconsider, or feel this other tug. Speaking of Missy—I watched the clip where you’re talking about the ways that music rides in the work. I think about improv and the ways the materials move, just responding to what it’s doing. Even if I had a plan, letting these impulses lead me to these new discoveries.

BIGGERS: There’s a sense of improvisation in your work that I really respond to. There’s so much improvisation in quilting and textiles in general; there’s patterns, but you riff on the pattern. When you start looking at traditional patterns, and then you look at Gee’s Bend, you see there’s a whole evolution of visual language that’s happening between those groups and those timeframes. I think you’re encapsulating that. Plus, there’s the international aspect of what you’re doing, how it’s tapping into so many ancient cultures. It’s really rich. How is L.A. right now? You’re there artistically at a very good time. How long have you been living there?

BRACKENS: I’ve been in L.A. for five years. In the last two years versus the first three, it is a different place. The amount of energy that is in L.A. in the art world… it feels like it’s changed ten-fold. When I first got here, I felt the disconnect. I felt the sleepiness of it all. But now, minus COVID, there’s so much happening here at any given time. I feel like I’ve found my people. I’m getting to watch them all rise in the ranks, which feels so great. I remember when I first moved here, I was reading South of Pico, and I was like, “This is this mythical place where all of this stuff is happening.” I feel like the clock has started over, and I’m like, “We are these people. We’re in the same terrain sharing the same experiences of some folks over 50 years of time.”

Sanford Biggers, Khemetstry, 2017. Antique quilt, birch plywood, gold leaf. © Sanford Biggers and Marianne Boesky Gallery. Photograph by Object Studies.

BIGGERS: South of Pico encapsulated all the history that had already gone through L.A. I grew up knowing a lot of those people. Those were early mentors of mine. I interacted with so many of them. Like you said, L.A. had its sleepy moment. It was always burgeoning. Then all of a sudden, boom! It just started hitting so hard. It’s nice to think that that energy is back in L.A., reinvigorated and re-envisioned by a younger group of people who are probably much better networked and have a lot more eyes on them. It’s an exciting time to be there. I’ve considered coming back there many times.

BRACKENS: Come back.

BIGGERS: I’ll see how it goes after this flight. What’s coming up next for you?

BRACKENS: I’m opening a show at Oakville Galleries alongside a Senga Nengudi show, which I’m excited about, as we talk about South of Pico—getting to touch those nodes of thinking about migration, the underground railroad, and textiles’ mythic connection to that. It was really exciting to read some of the things you were saying about the importance of holding that mythology in our consciousness.

BIGGERS: I see it in your work too. You have anecdotes. You have narrative. You have references, whether it be biblical, poetic, personal. I like that it’s prevalent in your work, but it doesn’t overpower the work. It’s just one of the rich elements. It feels good to know that you’re putting that kind of depth in the work.

BRACKENS: Thank you.

BIGGERS: I want to hear you do the rest of the song. You were slick with that.

BRACKENS: There’s also a really good theoretical craft essay that references that song too, so it was both to Missy and to L.J. Roberts.

BIGGERS: Hey, there we go.

BRACKENS: Missy didn’t know she was informing me.