art!

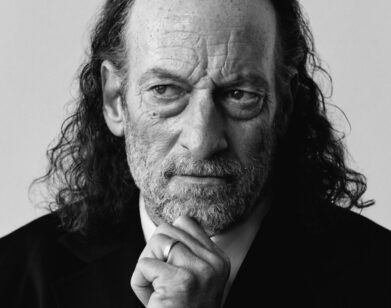

Sam Mckinniss Is Reimagining Hollywood Iconography in a New Medium

Michael Ovitz has made a name for himself as a driving force in Hollywood since the 1970s, but he’s been one of Los Angeles’ beacons and bellwethers of still pictures for just as long. A fearless collector and champion of contemporary art, the entertainment uber-mogul has built up his own museum-grade art program, which includes a private exhibition space in his Beverly Hills home. In recent years, Ovitz and his curator, Viet-Nu Nguyen, invite artists to create site-specific, one-of-a-kind installations and projects in the space. Ovitz and Nguyen acquired the collection’s first Sam McKinniss painting in 2019: a still of Julianne Moore from her performance in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia.

It was just over a year later that the pair hatched an idea (with the help of Ethan Buchsbaum of Almine Rech Gallery) that felt like a match made in Hollywood heaven: The Ovitz Family Collection would stage an exhibition of the young New York painter’s latest works devoted to movies. Over lunch—and a shared love of cinema—Ovitz, Nguyen, and McKinniss discussed the prospect of a series that takes Titanic and Eyes Wide Shut as its starting point. Soon after, a global pandemic struck, forcing the trio put their fledgling project on hold. Now, all these fragile months later, an exhibition is born: “Costume Drama,” a suite of 21 paintings, premieres this month and runs until October. Using iconic, pop-laden film scenes as his springboards, McKinniss has created a collection of paintings marked by decadence and defiance. Below, Ovitz, Nguyen, and McKinniss talk Hollywood, Cindy Sherman, movie magic, painting candlelight, and why Schindler’s List could never be in color. —CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

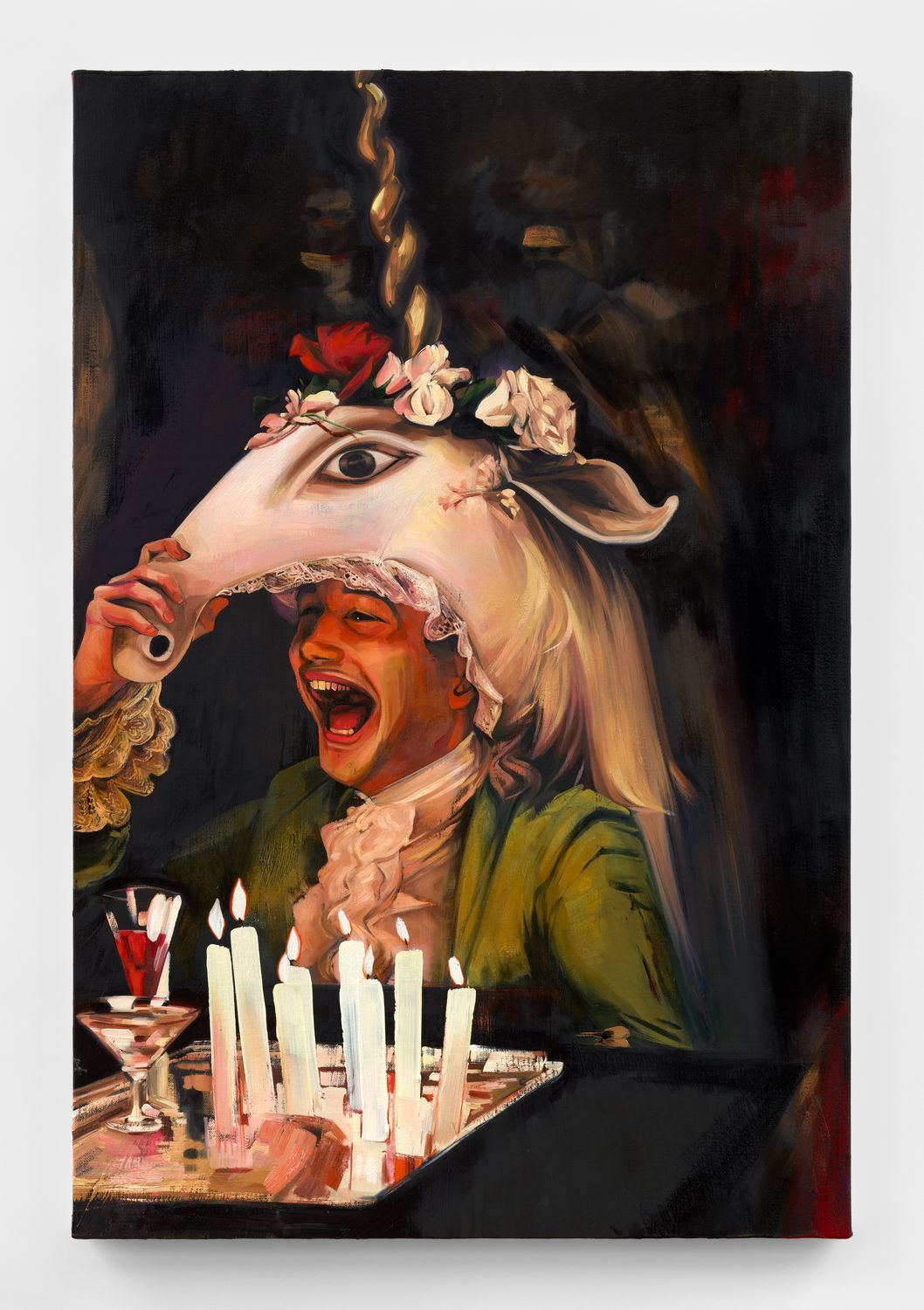

“Wolfgang,” 2020. Oil on linen.

VIET-NU NGUYEN: We’ve been talking about this project since early 2020, right before the pandemic began. We had lunch at Michael’s house that February, and it was the first time I saw anyone give an elbow bump. Sam, how did the past year influence this particular group of paintings?

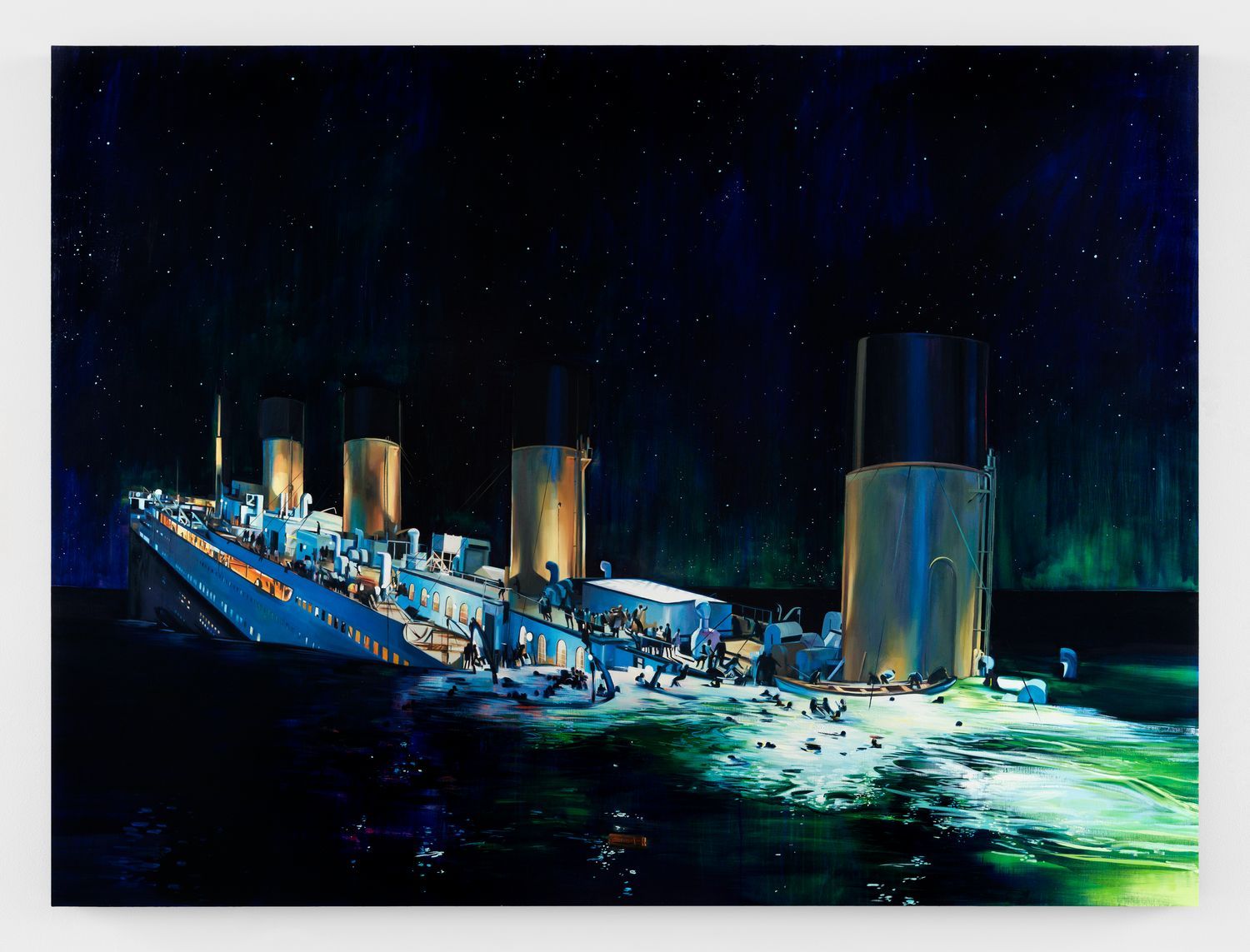

SAM MCKINNISS: That lunch was very warm, and it did not take very long for that nice feeling to fade because it was immediately followed by global chaos, uncertainty and imminent threat. I wanted this show to be contemporarily relevant, but I also wanted to try making “history art”—to make work that represented the time we were in. The best way I could think to do that was by using language taken from “the industry” that you work in, Michael. I wanted the show to feel portentous by using imagery borrowed from costume dramas or period pieces or things that looked like they were important to the past, while also keeping a watchful eye on the present. My thought was, “Wouldn’t it be amazing to recast and reimagine Eyes Wide Shut aboard the sinking Titanic?” That was my initial plan. It seemed a good idea to bring the orgy out from behind closed doors and into first-class aboard James Cameron’s sinking ship and see what effect that had on my imagination. Both movies leave a residue on my memory from when I first saw them as a teenager. Combining the two films felt very 2020 in a way—like, the party was really, really, fun, and then all of a sudden, it’s all just going down the drain. Then I wondered, “What other characters would it make sense to bring into this orgy at sea? Who else should be there?”

MICHAEL OVITZ: I loved witnessing an artist referencing and transforming the medium I worked in—moving pictures—into a single image, and your interpretations are so full of emotion. All the subjects are caught in the appropriate moment. I bet if I put the directors of these films into a room with you and asked them to select some of their most important shots, you’d both be aligned on a good number of the scenes that were chosen. The paintings aren’t just single frames—they remind the viewer of what happened before, during, and after this scene. In other words, your images unfold like a condensed movie. I knew that about your work from the time I saw the painting of Julianne Moore that we acquired—there was a look in her face that went beyond a still photograph. It was like the kind of work that Cindy Sherman did as she came to fame. I do feel you take a moment in time—of light projected through a celluloid frame—and bring it to life. When Martin Scorsese did Gangs of New York, I gave him a book on Rembrandt because Gangs of New York was set in a period of time when light either came from candles or daylight. Every so often, these inventoried images come out in a painting or in a movie or in a book. Your paintings go from Old Masters all the way to Contemporary—from Titian to Cindy Sherman.

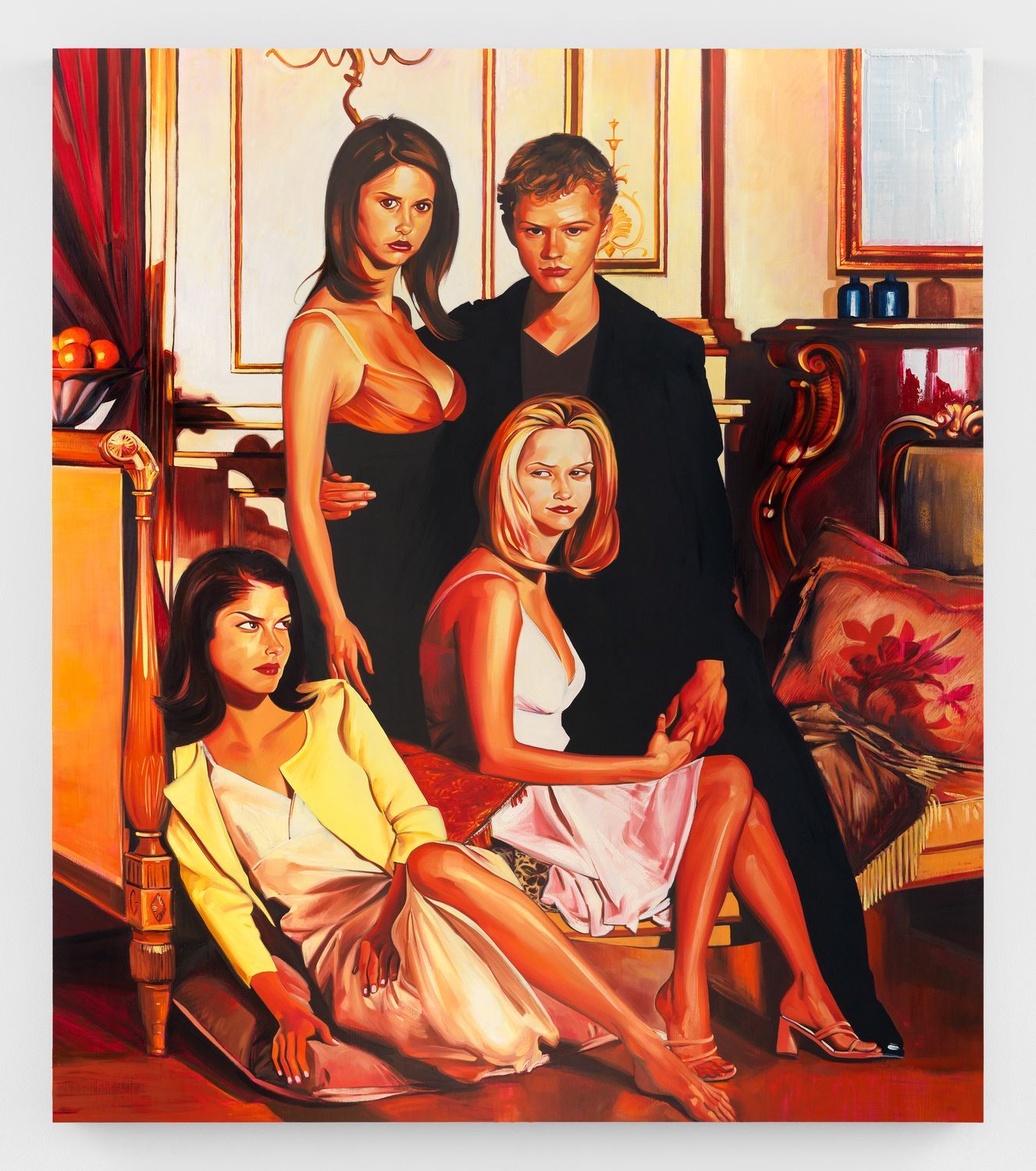

“Kathryn, Sebastian, Cecile, and Annette,” 2020. Oil on linen.

MCKINNISS: I like that you keep mentioning Cindy Sherman, because not a lot of people mention her to me. When I was in art school, I would make watercolor studies of her film stills. I was trying to figure out exactly how the drama was constructed inside of a still image, not a moving picture, but a still image that looks like a movie. It was very instructive to copy her work. The best art I’d resonated with before college was stuff that I had seen in music videos or at the cinema. And I’ve been trying to understand the process of montage ever since—which is still image, still image, still image, in quick succession. There’s no narrative-building in a dramaturgical sense. It’s just an impression of a narrative being put together by all these rapid-fire images being thrown at you, which is the experience I grew up with watching MTV. I suppose, it’s something that I’ve been trying to work out ever since.

OVITZ: As human beings, our brains react from stimulus to response, and the stimulus of a single image creates a multiplicity of responses, especially when you’ve seen the reference material. I’ve seen Titanic a half dozen times, so when I look at your painting, I replay the movie in my head. Stanley Kubrick was a client of mine. Very few people know that. But there is a photographer who worked mostly in Europe and who had extraordinary impact on Kubrick’s work. The photographer’s name was Jacques-Henri Lartigue. He was very famous in certain circles in Europe. Lartigue would catch the moment the way you do. Your Wolfgang is a movie still, yet I can remember that scene [from Amadeus]. I can actually look at the image and hear him [actor Tom Hulce] laughing. To me, that’s the ultimate form of communication.

MCKINNISS: That painting was fun to make because I knew I had to use glazes on all areas except for the candles, so that everything but the candles would have a kind of amber patina to it. The candles would stay very bright and nothing else. The candles would look like they give off light, and everything else would bask in the glow. But I have to say, usually I don’t have much access into your world, the world of film, except as a consumer. But I guess I have an impressionable mind. I go to watch movies because I enjoy seeing them. But I’m looking at them as finished compositions, as color, as poses, as moods and whatever else is being projected at me. But you see it from the other end, from their making.

“Jen Yu,” 2020. Oil on linen.

OVITZ: A director will work for 12 hours, which is the max they can do on set, and they will get, if they’re lucky, two minutes of usable film for a movie. You, as a painter, will work for a similar number of hours to get to the same place. With celluloid, the director draws the shots and scenes on what’s called a storyboard. You paint them. You both have the moving image in your heads, and it all ends up as something very specific. The similarities are abundant, but the styles and the art form are 180 degrees from each other. That’s why the tension in your work is so interesting. I wonder, ten years from now, will your subjects still be films? Or will it be streamed programs, which are technically television programs. Obviously, the cultural agenda and cultural iconography have changed and will continue to change. The delivery system has also changed. So, it’ll be interesting to see what you do, Sam. What will stimulate you and what will you remember? What will influence you going forward? The idea sneaking away and telling a little white lie to your parents about where you’re going in order to go watch Jurassic Park…. Kids don’t have to sneak out to watch movies anymore.

MCKINNISS: Maybe that’s just one other thing to add to the list of new pandemic realities. I haven’t been able to go to the movie theater. Going to the movies is not the same as streaming them.

OVITZ: It’s a completely different experience, having people fill the room.

MCKINNISS: And the enormous screen, that’s the best part. The totally pitch-black room and an enormous screen and the huge sound. There’s nothing like a dark room. I want to ask you, is there a film that you come back to and think about on a regular basis? One that you believe has had an outsized effect on how you understood the world, or yourself, or how you understood life?

OVITZ:, Sam, I’m just a fan. In the height of my career, when CAA handled the majority of the talent in the entire film business, I never thought of anything except, “did I enjoy what I was seeing?” I was more interested in being transported to the mind and world of another human being. I was not concerned about intellectual stimulation with film— that happened later. I allowed art to do that for me. I was concerned about being entertained when watching a movie. As an agent, I always felt that you could get the best of both worlds. You could get the aesthetic and you could get the commercial, and if you pushed them together, there was a place where they met and you ended up with something spectacular. A Scorsese movie, a Spielberg movie, Dances with Wolves, Out of Africa, Casino, Goodfellas, Schindler’s List are all great examples of that. Schindler’s List was an intellectual movie, a visceral conjuring of a horrific time in history, but Spielberg’s adept storytelling and meticulous attention to detail attracted a wide audience. Everyone told me Rain Man was going to fail because it was too intellectual. I said to everybody, it’s not going to fail, it’s a family story. And it was the number one movie. We were told it would not do one nickel in Japan, and it was the number one movie in Japan too because it’s all about family.

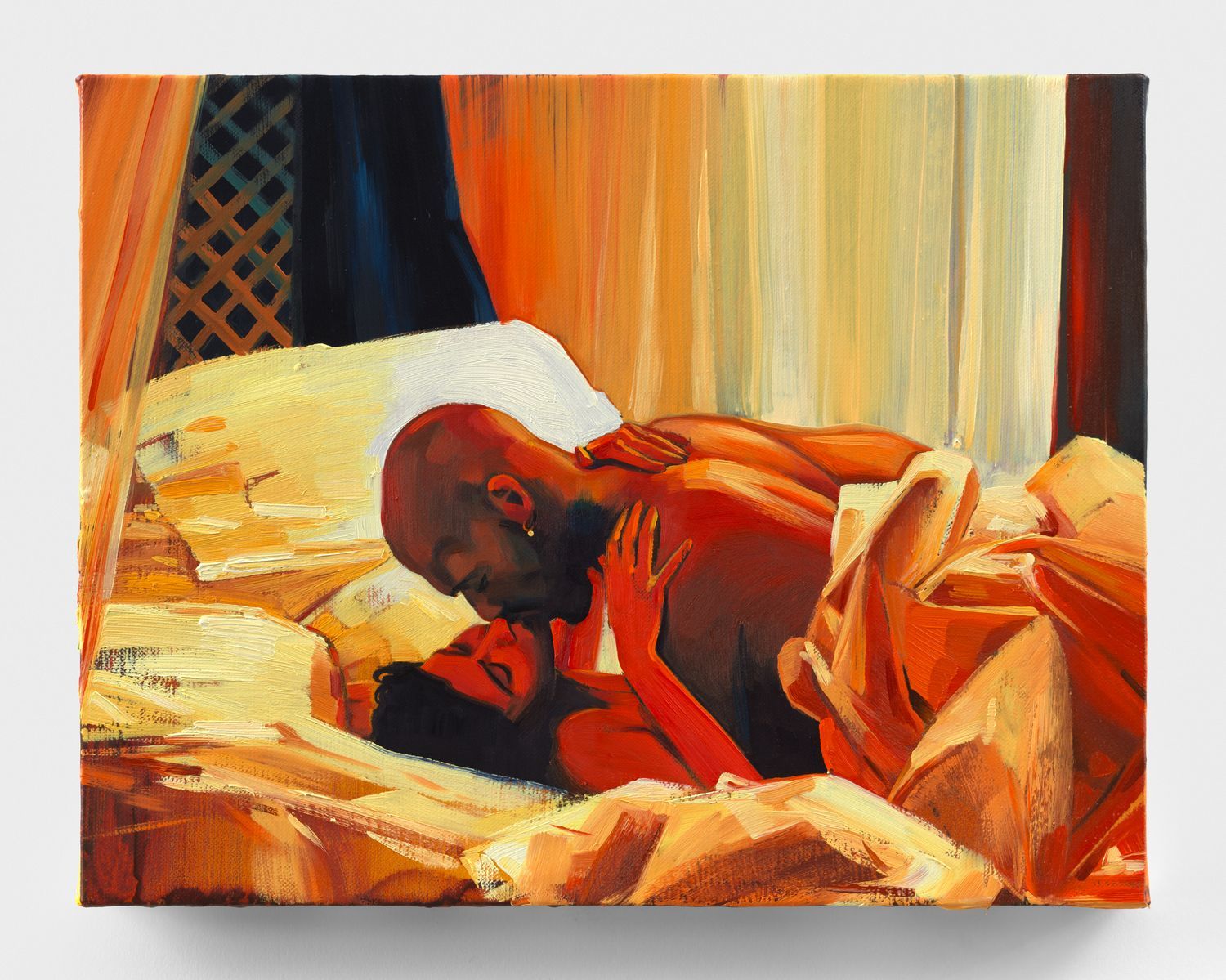

“Othello and Desdemona,” 2020. Oil on linen.

MCKINNISS: I watched Rain Man again recently. I hadn’t seen it since I was young, and I was taken in all over again. An entire world inside of that film and at the same time rather expansive. It goes lowbrow at the same time that it goes highbrow. I want to ask, is there a movie that comes to mind that you saw before you got into the business?

OVITZ: I lived four blocks from a movie studio, and I got my first job when I was 16 working at Universal Studios as a tour guide. To prep for that job, I had to watch all the great black and whites of the ’40s and then all of the big CinemaScopes of the ’50s, those crazy over-acted period dramas. Orson Welles created Citizen Kane at 27 years old, and to this day, it remains one of the greatest movies ever made. I’m a mega Frank Capra guy. It Happened One Night never left me. And Lost Horizon. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it. Lost Horizon is such an uplifting movie for the soul. For a process fan like me, the movie is a triumph in filmmaking because part of it takes place in the Himalayas, and Capra wanted to show the fogged-up breath of human beings, so he shot those scenes in a meat storage facility. The stuff you see in movies is crazy. Why did I respond to Ghostbusters, or Stripes, or Meatballs, or any of those comedies? I thank Frank Capra for that. When Michael Crichton gave me the story of Jurassic Park, I thought about big, spectacular Cecil B. DeMille movies that I hated on some level because they were so overacted, but I loved to watch because they were challenging to make. I always rerun old movies. I reran Ben-Hur recently. It’s beyond overacted. It’s kind of funny, but it’s brilliant in conception for the time that it was made. Those are the kinds of things I think about. I think about old films. You learn so much about lighting when you look at black and white films. One of the biggest fights I ever had was with the head of Universal Studios over Steven Spielberg’s absolutely firm insistence on shooting Schindler’s List in black and white. They said it would never sell videocassettes. And here again, backing the artist paid off for me. You have to back the artist. It’s their vision. I can’t imagine seeing Schindler’s List in color. It wouldn’t feel right. It wouldn’t feel real. It’s like Barry Levinson’s touch on Rain Man. That film went through four directors before Levinson did it. When your stomach meets your brain, something amazing pops out, and that’s what happened to Levinson on that film. He had all the right impressions and instincts. Cincinnati was his idea.

MCKINNISS: What’s interesting to me right now in terms of art lingo, the definition of “Impression” has changed. “Impressionism” means 19th century modern French painting. But in our lifetime, “Impression” means seeing an image that makes an impact on you or your behavior. Does it stick with you? Does it influence your consumer habits just for having come into contact with it somewhere on a screen? That’s a big shift in the definition of just one word from one century to our century.

OVITZ: Yeah, completely different.

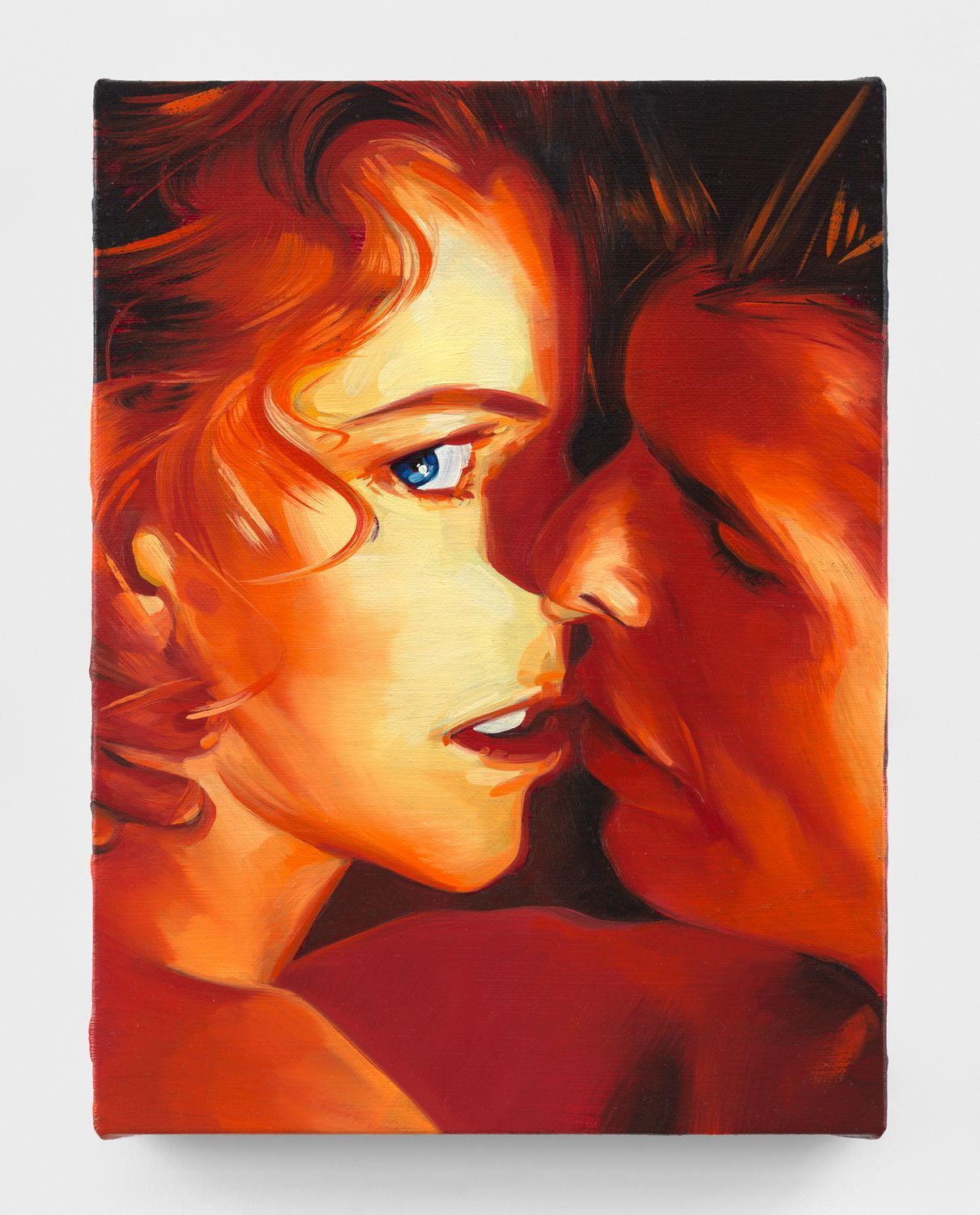

“Alice and Bill,” 2020. Oil on linen.

NGUYEN: You both talk about the impression or residue of films, but has the residue of 2020 changed your understanding of these films that you once loved? Michael brought up Gone with the Wind. This film was actually taken off certain movie catalogs this past year. When it was put back on, introductory text and video was added to give more historical context about the film’s portrayal of slavery and the antebellum South. So much happened in the past few years that I, personally, can’t look at many of the films that I have loved in the same way. Every Woody Allen film, for example. Do either of you feel that way about any movies?

MCKINNISS: I can’t watch Kill Bill anymore in light of Uma Thurman coming forward with her experience of making that movie. I don’t feel comfortable enjoying it. I know it’s a great movie, I know Quentin Tarantino is a great filmmaker, I know that it resonates with me, and I know that Uma Thurman is an amazing actor, but just knowing now what’s come out about the backstory, that she was nearly killed on set, I can’t enjoy it. Even though it’s been one of my go-tos.

NGUYEN: It was on your initial list of formative movies.

MCKINNISS: Totally. But it’s difficult to get into it. Part of that is because the moment has passed—it’s not so current anymore, obviously. But without even knowing her, I have real affection for Uma Thurman and for her work, and that makes me feel protective of her. I didn’t watch much that was new this past year. Titanic totally holds up. That’s a disaster movie that just has it all. It was oddly comforting during this time to be onboard with those characters, to be there with them and do it over and over again. I watched it at least four times while I was making this show.