In Conversation

Pippa Garner and Hayden Dunham on the Struggle of Being Inside Bodies

Clifford Prince King, Portrait of Pippa Garner, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

On the occasion of Pippa Garner’s first solo show in New York City—at Jeffrey Stark gallery in Chinatown which runs from May 14 to June 13, 2021—the 78-year-old trans-disciplinary artist got on the phone with one of her fans and friends, the artist and Hayden Dunham, to discuss, among other things, losing their vision while still being able to see.

Early last year, I received a phone call from Pippa Garner, who couldn’t see. I lost my vision a few years ago, and a friend set us up. We didn’t know each other, and were both without eyesight at different points in the conversation. It was, in all respects, a blind date. The last time we spoke, it was late at night, and a sweatshirt Pippa made that says “Bad in bed” on the front was resting on my floor. Christopher Schwartz gave it to me on her behalf when I came to see Pippa’s show The Bowels of the Mind at his STARS gallery near the Hollywood Walk of Fame. “The pieces are breathing,” I said to Pippa on the phone from Hollywood. She made an inflatable sculpture that rises and falls like lungs, meant to represent the moment of artistic inspiration, the Brainstorm.

I first encountered Pippa Garner’s art when I was in high school. I cut a business suit in half and made it into a mini skirt after seeing her do this in Utopia or Bust: Products for the Perfect World, a book she published in 1984. Years later, I was visited again by this image of Pippa’s half-suit in Vogue, and connected how much her work has infiltrated and informed the world I am living in.

When Pippa and I talk, I’m usually in the bath and she is working. She works all the time. We compare notes about our research and progress: What will happen after we leave our bodies, how we want to die, what it will feel like to get a new operating system, how she got to her doctor’s appointments.

All of it is imagined for me. We have never seen each other, but through not seeing, our vision is infinite. I picture Pippa working out in her home gym made out of water jugs. She imagines the mist fountain I use to steam my eyes. Inventions that work and don’t work, for bodies that work and don’t work. Today, I don’t have access to vision, and she is seeing yellow. —HAYDEN DUNHAM

HAYDEN DUNHAM: I’m interested in what your experience was like being in your body historically, and then being in your body now.

PIPPA GARNER: There was something that always seemed odd about being saddled with a gender, or being isolated by your gender. Because the advertising, consumerism, in the background in my life, was very much gender-oriented. There were things for women and things for men. It was all-out masculinity or all-out femininity, macho or made up. And if you didn’t feel that yourself, you felt uncomfortable. That was what they wanted, so that you would buy their products. In the mid-’80s, when I first started playing with gender, I thought, “Why am I forcing myself to become more masculine?” I was tall and athletic, more or less. But I had this insecurity about lacking what it really took to be masculine. I finally said, “Fuck this. Why am I conforming? I don’t care. I’m just me. I’m this individual unit that’s here, going through an episode on Earth, and I’ll do what I want to do.” Nobody I knew had really thought about transitioning except in the ‘50s, there was… What was her name?

DUNHAM: Christine Jorgensen?

GARNER: Yes, of course. She was a G.I. during World War II, not in combat, but anyway. She was drafted and after the war, she got this surgery. She was a very, very shy person and didn’t want any publicity. But the press got hold of it and it was a huge furor in the newspapers. One of them, the title of the article was: “GI Goes Abroad, Comes Back a Broad.”

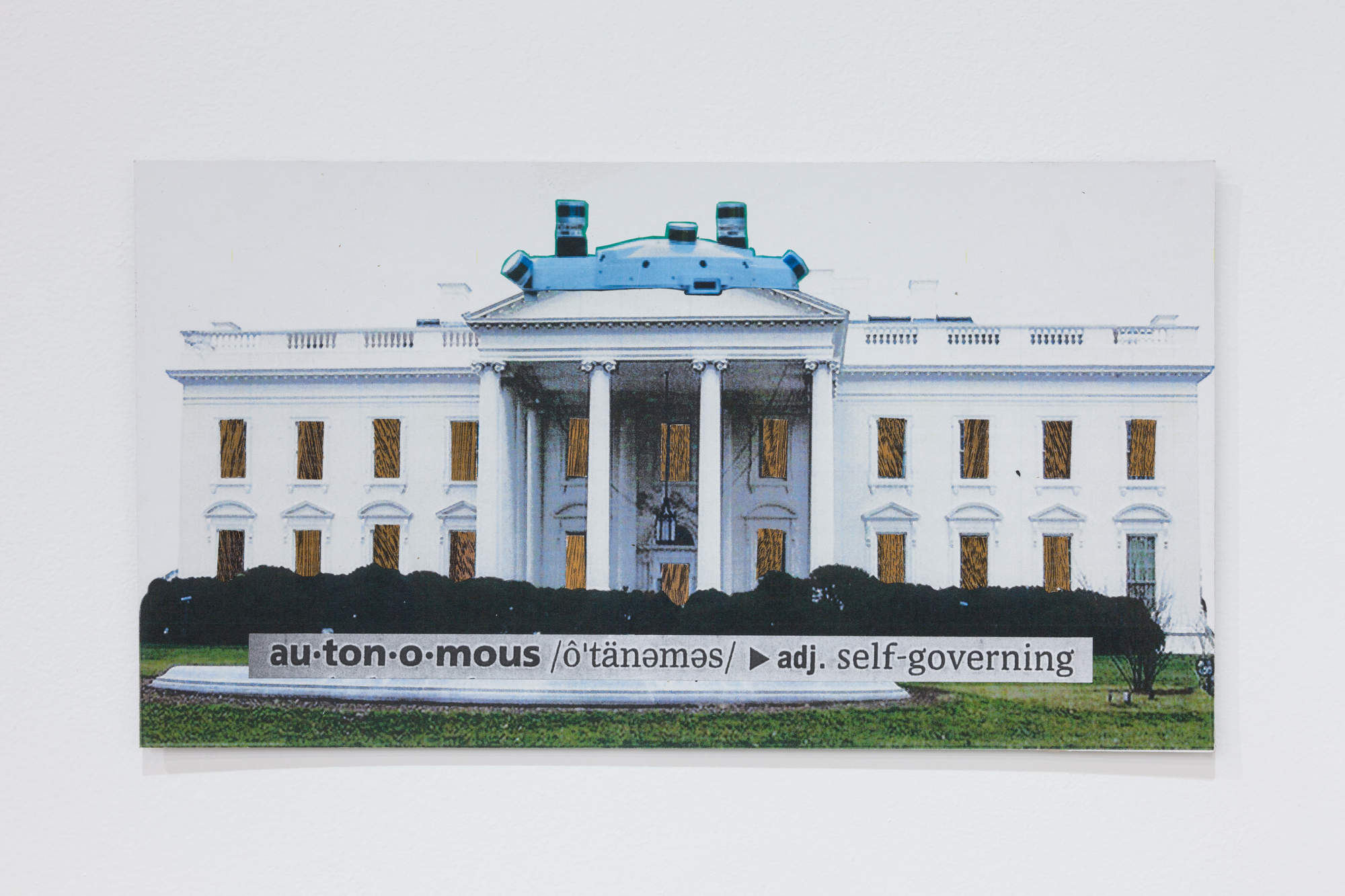

Pippa Garner, “autono*mous,” 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

DUNHAM: Wow.

GARNER: That was the only trans person that I knew of back then. The idea of experimenting with gender intrigued me. At one point, I thought, “What if I did that?” I wanted to have a different relationship with women, for one thing. I also sensed that this would save me from ever becoming stereotyped or getting into a position of really being comfortable, socially. And I think that was something I dreaded. My whole attitude is like this. It’s like how I never really considered L.A. home. It doesn’t feel like home here, it never has. But I’m bound to L.A. because somehow, the fact that it’s a little off is a good creative environment for me. I need to be in a place that doesn’t quite feel comfortable.

DUNHAM: That’s how I feel about being human. It’s not a comfortable place, but it’s a creative place. Like my body is an open container that can be augmented and even cared for to hold me here for this lifetime. It has been a challenge to find ways to live inside of it. What did it feel like when you first started taking hormones?

GARNER: Oh, it was amazing. It was totally transformational. I didn’t notice anything for the first month, I think. And then all of a sudden, this completely locked-in, linear sex drive started to fan out and become more of a peripheral sensuality, rather than just pure sexuality. It was a real revelation because I thought this is obviously what we need. Probably the only piece of wisdom I’ve ever gotten in my life was to see that what we really need is to balance the male and female influence in our leadership. That’s what was wrong: the patriarchy. The 20th century was complete patriarchy, men ran everything. So now it’s refreshing to see that softening. We don’t have blinders on anymore.

DUNHAM: We don’t have blinders on anymore. Pippa, I love that. That’s really inspiring.

GARNER: I don’t want any more wisdom. I don’t like wisdom. Wisdom to me is the end game. I’d rather just have soundbites of knowledge, just pile them up and then play with them. I don’t want to know too much about anything. I tell people, the reason I had the sex change was that I wanted to find out if men’s brains really are between their legs.

DUNHAM: What do we think, Pippa?

GARNER: I have more. I came out of the closet and into the woodwork. I could never find the right girl, so I decided to build one in. I didn’t want to be the same gender as god. We all know that god is a man, right?

DUNHAM: Pippa.

GARNER: I’m female, but not period correct. See, somebody told me to go fuck myself and I took him literally.

DUNHAM: You’re so funny. This is a perfect opening to your relationship with the jester.

GARNER: I only have my own interpretation of things that I’ve picked up through reading and experience, so let’s see. Within the court systems in Europe, there were jesters and fools. The fools weren’t part of the court in any formal way, or they didn’t have to behave according to the rules of the court. They could be slobs, they could eat with their hands if they wanted, they could do anything. And they were supposed to actually, because that was in contrast to what was considered important, to the traditions and regulations of the ruling structure. Fools could play with it. Kings tended to have fools who were very smart and had insights and wisdom. They knew what was going on in a deeper way. If your attitude is that things are amazing but they’re also absurd, you’re able to see patterns that link behavior. The fools were like psychologists, in a way. The kings would have somebody like that, maybe several, who would give them advice. They could interpret the culture in a way that was not bound to traditions, and just get ideas, feelings and thoughts. And sometimes that might save the king’s life. If there was a plot to kill him or something, the fool might be able to pick that up before anyone else. What the fool is really, I think, is a transitional link between true depth of understanding and the superficial level that most of culture survives on.

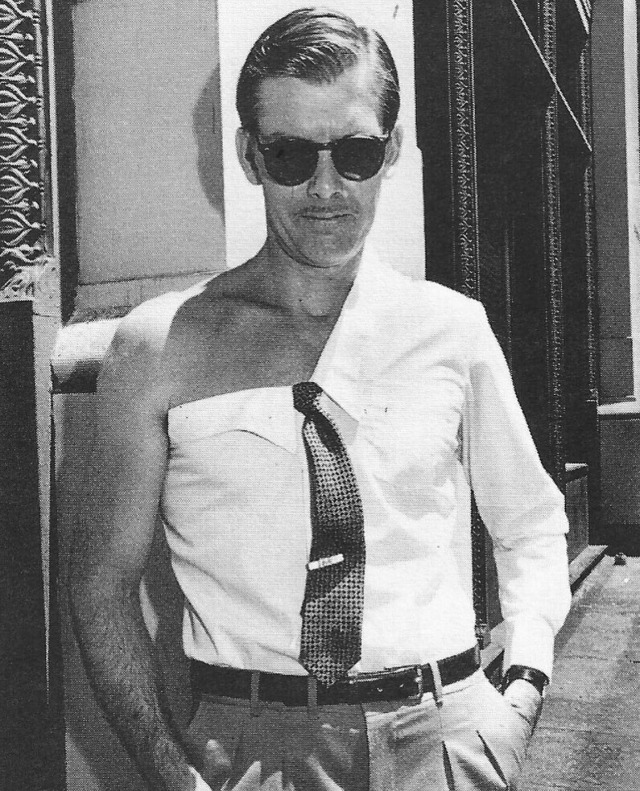

Pippa Garner (formerly Philip Garner), NEOPOP Businesswear, 1981. Courtesy of the artist.

DUNHAM: Sounds like you.

GARNER: Oh, I don’t know. What I’ve created is a couple. It’s like I’m on a constant double date within my own body.

DUNHAM: Could you tell us more about that?

GARNER: I see the body almost as a toy or a pet that I can play with. What am I going to do with it? Do I just let it go and then watch it deteriorate? What are the options? I can change the shape of it, I can exercise and make it look different. I can style it up with fashion and all the other things that you can do to create an image with your body that other people respond to. And I’ve done that. I am an inside and an outside. I see them as one inside the other, and that’s an issue I’m having at the moment, because I’m at a point where the exterior part is not behaving as well as it should, and the inside part is aggravated by that, saying, “Come on!”

DUNHAM: So much of your recent work is about the body. I’m thinking about what I just saw in L.A., The Bowels of the Mind sculpture that breathes, and Human Prototype, that’s like two humans stitched together, one of God’s abandoned designs. I loved seeing these sculptures next to this huge portrait of you [by the photographer Clifford Prince King] hanging in the gallery.

GARNER: I’d love to see that image sometime. I couldn’t with my vision. I hope it shows my tattoos.

DUNHAM: It actually is an extremely beautiful photo of you. And yes, it does.

GARNER: Oh good. It’s always nice being naked in public.

DUNHAM: What’s your vision like right now?

GARNER: Terrible. I had this medication. I don’t know if I mentioned that.

DUNHAM: Yeah, it was making you sick.

Pippa Garner, “The Bowels of the Mind,” 2021. Courtesy of the artist and STARS Gallery.

GARNER: This cancer treatment medication I was prescribed was making me feel really sick. And also, it seemed to be affecting my vision more severely. So I went off it, then back and forth with it, trying to follow the oncologist’s instructions. I’ve had various treatments. I have to do eleven treatments a day for my eyes for the rest of my life. Five of them are for tear production. Three times a day, I have to do hot compresses, and then I have another medication that’s supposed to increase that tear production. I don’t know if it’s working or not. What’s done now will seem archaic. There’s still a lot of guessing and experimenting. Meanwhile, everything has a side effect. Anyway, I didn’t want to get into all that now. I just want to hear a friendly voice for a moment. Are you feeling better?

DUNHAM: Can I tell you something?

GARNER: You mentioned you were having a sort of a down period, too.

DUNHAM: Yeah. Well, I’ll tell you something that’s interesting. My eyelashes have grown five times the normal amount from that same medication that you’re on. I also was on it, taking it eleven times a day when I lost my vision. And now one of the side effects is that my eyelashes turned white and grew extremely long. Every morning when I get up, they’re all twisted up and I have to kind of weave them into each other to make this eyelash shelf or shade structure over my eyes. They grow really, really long. And then they eventually fall out and start over again.

GARNER: The compresses help with that. They keep the medication from causing them to get stuck together. It’s funny because it’s sold as a beauty treatment also.

DUNHAM: Blindness is weird. Being in darkness and in pain, I found that whenever I walked into a room I would upload a map and know where water was at any given time. There are a lot of parts of being in darkness that I like now. It really becomes about listening instead of talking. And waiting. It’s really durational when you’re in darkness, because time is not linear, or it’s much harder to track time. I can understand why it feels like forever, because it actually kind of is in a sense. It’s without time. Everything feels infinite.

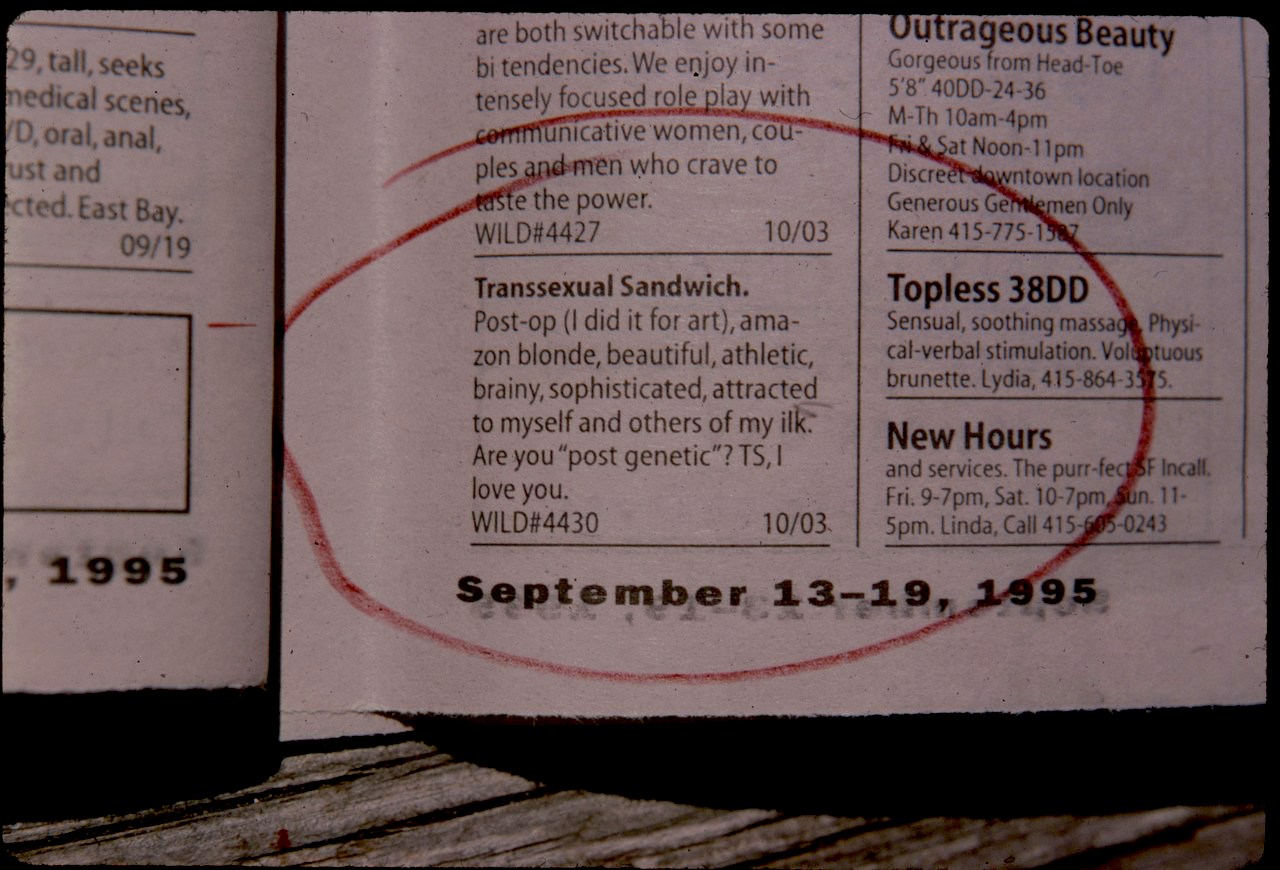

Pippa Garner, “Transsexual Sandwich,” 1995. Printed personal ad. Courtesy of the artist.

GARNER: It’s difficult. I think if I got back to having an acceptable level of vision, I’d be so grateful constantly, for the rest of my life. But you don’t think about that sort of thing unless you’re forced to.

DUNHAM: It has been helpful for me in unexpected ways. I had an idea to say a couple words to you and then you just respond to it, anything you want to talk about on that topic.

GARNER: Whatever you want to do. There has to be a leader and a follower in an interview. I mean, sometimes the follower takes the lead and then it spoils it.

DUNHAM: Okay. So my phrase is “Body versus vessel.”

GARNER: Oh, like a ship? Or like a blood vessel?

DUNHAM: It actually could be either. I was thinking about how our body is a container for us in this lifetime, and that we get to do whatever we want with it, as you said.

GARNER: When I think of “vessel,” the first thing that pops into my head is Noah’s Ark. Wonderful mess. The world is getting so bad that it has to be flooded out. The humans have to be killed by floods and this boat with pairs of animals floats above it to then start the whole thing over. The creator said, “Fuck this, this only getting worse. The answer now is to wipe it out and start over. So I take samples and put them in this vessel and put them away until everything else is gone and pure and whole again. The way I wanted it. Then they can start over with pure morality. A good world.” I don’t believe that it’s possible to have good without evil, it’s absurd.

DUNHAM: What do you think happens when we lose the exterior part of ourselves? The body, the vessel. Like in death, what happens to our operating system then?

GARNER: I have no idea. I am in this thing, a mix of being natural and something that’s beyond that. As humans, we can think. We can create things that don’t exist. In nature, things dissolve and go back. When something dies, it falls apart and goes back down into the earth and is recycled. This is true for an automobile, as well as a leaf. An automobile is made of things that are mined from the earth and put into this unique unearthly form. But when they go, they go, eventually. Mother nature hasn’t let anything go, it seems like it’s all contained. We have gravity that holds everything; it sucks everything towards the center of the earth. And yet moisture is able to overcome that and get up into the sky and come down again as rain or snow. Will I just dissolve? There’s no way to have any idea what happens. That’s it. I don’t know. The pandemic is a nice pause in the midst of a stagnant cultural period. We’re really going to see, I think, a change in the global timestamp. I think we’ll have made a big step toward a sense of humanity as a whole, and not as certain pockets that represent certain things. It will still have a long way to go, but I think we’re going to see an improvement. Which is one reason I want to stay. Keep my health somehow. Be in shape for at least another couple of years, to see.

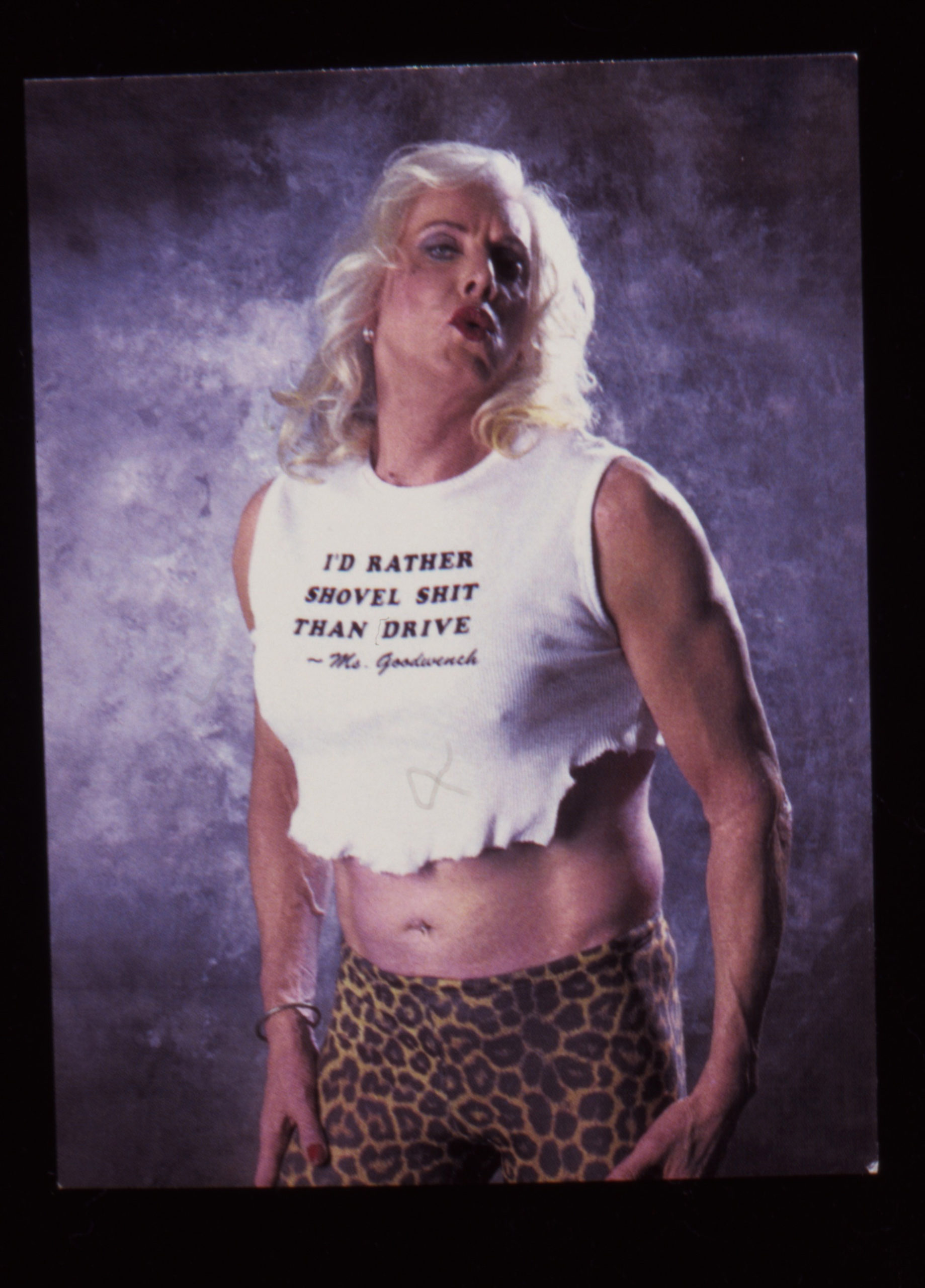

Pippa Garner, “Self-portrait (I’d Rather Shovel Shit Than Drive)”, 2004. Courtesy of the artist.

Pippa Garner’s show The Bowels of the Mind is on view at Jeffrey Stark gallery (88 East Broadway #B11, basement level, New York, NY 10002) through June 13, 2021