The Painter Djordje Ozbolt is Showing Us How to Regain Memory Loss

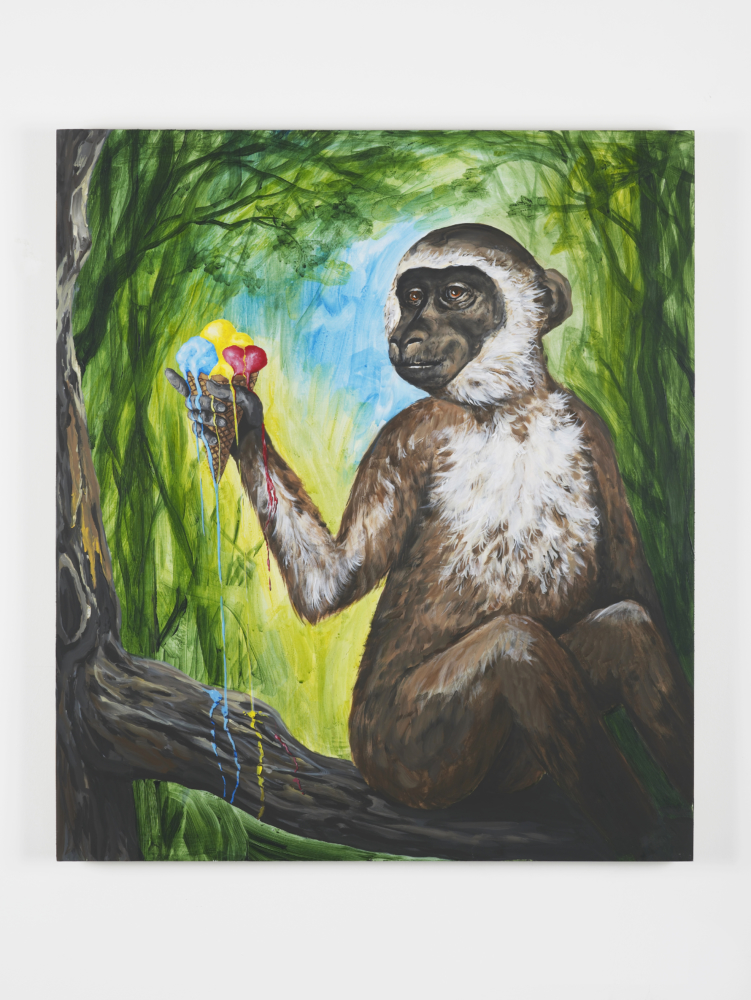

“Study For Regaining Memory Loss 1,” 2019

At this year’s Art Biennale in Venice, the painter Djordje Ozbolt will be representing the Serbian Pavilion for the 58th iteration of the event, titled “May You Live In Interesting Times.” Ozbolt, whose large-scale paintings are frequently called “dark” and “comic,” or some combination thereof, is an interesting painter, to put it mildly, who happens to be obsessed with time. The 57-year-old artist, who’s only shown sporadically in the U.S., plans to present a series of paintings, hung in front of a separate mural, under the name “Regaining Memory Loss.” The multi-layered piece, which features Ozbolt’s vivid colors, and surreal incorporations of the everyday (like the technicolor ice cream melting down a vervet monkey’s arm, for instance) is a meditation on the “imaginary ambient” where the fragments of memories gather. Over the phone, Ozbolt spoke with artist Scott King about attacking the canvas, comedy in his art, and knowing when a piece is finished. “It’s a bit like life itself,” Ozbolt said, “You are dead as soon as you are born, but you go on living, hoping for the best.”

———

SCOTT KING: Do you ever try to change what you do in a radical sense? Do you ever consider becoming an austere minimalist?

DJORDJE OZBOLT: I do! That is, I try to change. It’s not that I get bored of what I do. I just think it’s good to try and be open and keep it fresh. I don’t always succeed. It’s very difficult to change. I mean, radically change. Only the real masters succeed in that. And minimalism? I’ve never thought of becoming a minimalist. Maybe I should try. It’s all about keeping it challenging for myself. It’s the challenge that makes it thrilling and uncomfortable.

KING: You once told me that you never get “painter’s block.” Instead, you just stand in front of a canvas with a paintbrush and something always happens. Is this still the case?

OZBOLT: More or less. If you approach a blank canvas without any ideas, it’s the process of applying the paint that kickstarts it. It can be very rewarding in the end. It can also take a while to arrive somewhere. I do like it when nothing becomes something through the sheer process of painting. Sometimes it’s easy, sometimes it’s not. Instead of contemplating in front of a blank canvas, I believe in attacking it with everything I’ve got.

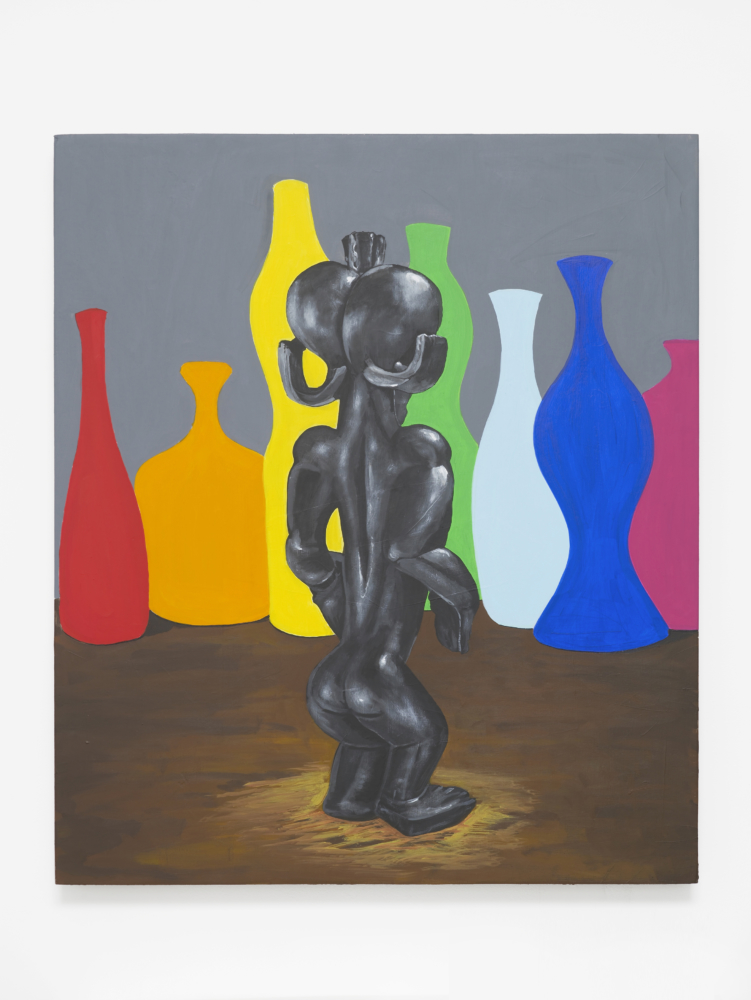

Patience is a virtue (2018)

KING: Do you throw much work away? Do you ever paint over something that, a day ago, you were pleased with?

OZBOLT: Constantly! These days I often paint over and dispose of the work. In the past, I liked the idea of keeping everything. I liked the overview and being able to see the process of getting to a work that I actually liked. This approach was abandoned as it became confusing, and it was impossible for me to distinguish the good from the bad.

KING: Who were your influences when you started? I always think there’s a bit of [Martin] Kippenberger in your painting.

OZBOLT: I don’t really know. I’ve had a lot of influences. The first were the ones I had books on: The Surrealists, Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Hannah Höch, to name a few. When I started taking things more seriously, I discovered other artists, of course. And yes, Germans were a pleasure to discover: Kippenberger and Polke to Richter, Baselitz, and later Albert Oehlen — one of my all-time favorites along with Kippenberger. But to be honest, I don’t really know where to start regarding “influences.” I do go back to Kawara, Picabia, Goya — but art was always just one of my interests along with films, comic books, music, and politics.

“Study For Regaining Memory Loss 2,” 2019

KING: Do you read much? And if so, what? Does this affect your painting?

OZBOLT: I do read, but definitely not enough. I read on holidays and attempt to read in the studio, but painting always gets in the way. As a very keen young man, I read much more, of course. My mind was chaotic and so my choices were eclectic. I also had slightly romantic tendencies and the possibility of worlds outside my own was addictively alluring. This meant that books gave way to traveling and trying to place myself center-stage. This is a dangerous approach. But it did give me exposure to a huge array of different experiences — both good and bad. Having said that, I do believe that reading and the things we read stay in the brain and are channelled, like all experiences, into the work itself.

KING: Do you ever worry you’re not being taken seriously enough — by which I mean, there is a lot of comedy in what you do, but is your painting inherently serious?

OZBOLT: No, I don’t worry. I’m often told my paintings, and their titles, are funny, but I do simultaneously engage with the serious as well. The thing is, I often find it easier to communicate through humor, which doesn’t mean I take certain issues lightly. Is my painting inherently serious? I’m not sure about that. I think people generally perceive painting as being more serious. It’s still seen as a more traditional form of artistic expression. But I think painting can and should be fun, for both the creator and the viewer.

‘Should I stay or should I go‘ (2018)

‘Should I stay or should I go‘ (2018)

KING: What’s the best series of paintings you’ve ever made and why?

OZBOLT: Even before I finish a painting, I am trying to make the next one. I have a tendency to change my mind, so my relationship with my work is never static. I was very happy with the piece “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” that I made a couple of years ago and exhibited in New York. It consisted of 50 small paintings, created as a kind of diary. I would come to the studio each morning and start the day by making one of the paintings. I consciously decided not to have a concept or plan, so each painting was a reflection of my thoughts on that day.

KING: How do you know when a painting is finished?

OZBOLT: I don’t really know. There has got to be a point where you stop. In my view, it’s finished as soon as you start, but you go on hoping it’s going to get better! A bit like life itself: You are dead as soon as you are born, but you go on living, hoping for the best.

KING: What are you doing for the show when you represent Serbia at this year’s Venice Biennale?

OZBOLT: My proposal for the Serbian pavilion in Venice is a combination of things from my practice, specifically a wall painting with paintings hung on top of it and a series of sculptural figures. The idea came from memories of growing up in Serbia (which was then Yugoslavia). I was interested in how memories unfold with the passing of time – how they change and become unreliable. So, I’m just contemplating what we do remember, individually or collectively, and what we choose to forget.