Art

Nile Harris and Crackhead Barney on Art and Exploitation

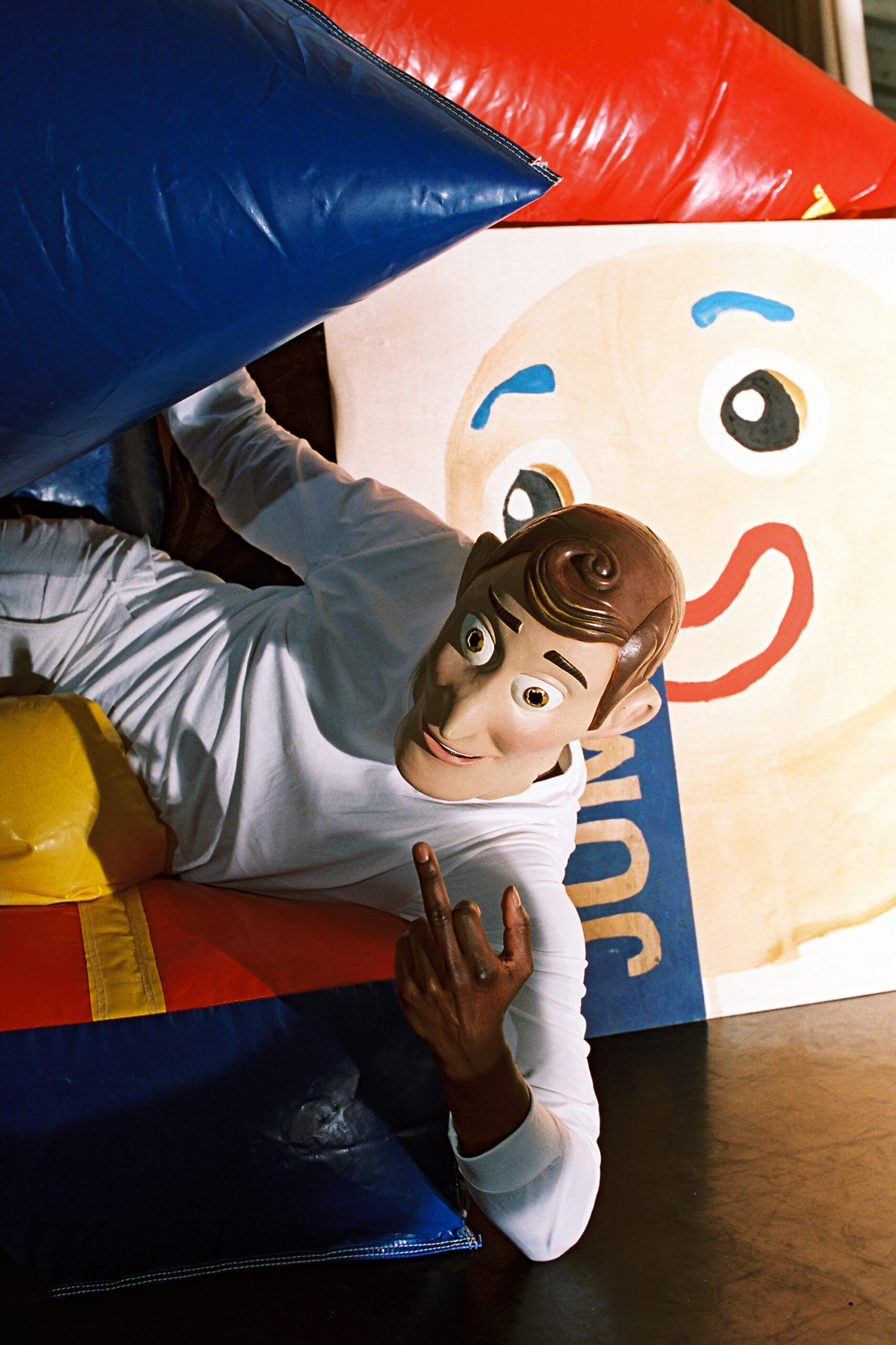

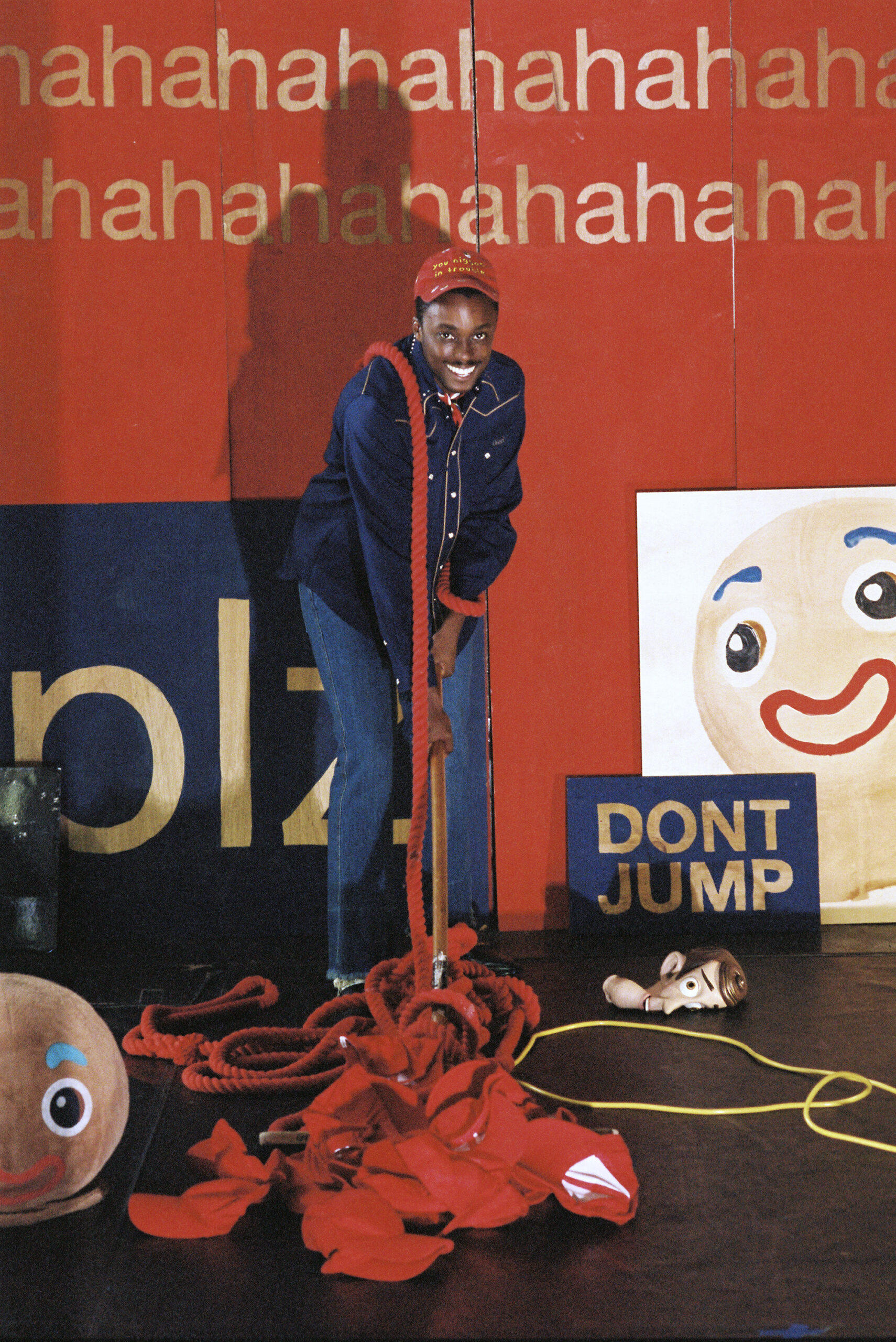

A children’s bounce house rigged with microphones. Two white women fighting over a vape. A surplus of red baseball caps reminiscent of the Trump era. These are just a few of the nihilistic ingredients that make up Nile Harris’s latest live performance, this house is not a home, set to run for three days this July at Abrons Arts Center in Manhattan. Nile is not only the creator, but also the work’s principal performer (his masked identities include a minstrel-like gingerbread man and Woody from Toy Story). Nile’s work has always tackled uncomfortable social issues, and while this latest encapsulates so many of his barbed artistic obsessions, it also serves as a tribute to his best friend and longtime collaborator, the filmmaker Trevor Bazile, who died in 2021. Nile, who recently became co–artistic director of the New York experimental theater group Ping Chong and Company, has been busily assembling his dystopian Oz, but he took time out of a rehearsal with his friend and fellow bounce house performer, Crackhead Barney, to hash out a bunch of topics they probably thought we’d cut from the interview.

———

WEDNESDAY 4 PM APRIL 26, 2023 NYC

CRACKHEAD BARNEY: Where’s Niles?

NILE HARRIS: I’m right here, baby. This is white-woman Barney in the nice new wig.

BARNEY: I’m Barbara Walters. It’s Barbara Walters interviewing you.

HARRIS: Oh my god. I’m so lucky. Barbara asks good questions. I feel so honored to be interviewed by a white legend.

BARNEY: I’ve been telling people that I’m a white woman, but unfortunately I’m getting treated like a Black coon nigger. I don’t know what’s going on.

HARRIS: People treat me the same way. I don’t know why.

BARNEY: White and privileged. This is ghetto-ass Interview, and they really want the magazine to sell.

HARRIS: And they can’t have white people on the cover. White doesn’t sell anymore.

BARNEY: White is not in vogue.

HARRIS: That’s why we can’t be on the cover. They want Black artists for the cover.

BARNEY: Black gay artists. They’re in.

HARRIS: Us white artists have to really struggle.

BARNEY: So Niles—

HARRIS: I love that you call me Niles because I performed last night and they put Niles Harris on the bill.

BARNEY: Fuck your name. I’m renaming you.

HARRIS: You think it’s better for my brand to be Niles?

BARNEY: Yeah, because it’s more like Miles Davis. And you’re living in plurality. There’s multiple people living inside you.

HARRIS: You can be Barney and you can be Barbara Walters all at the same time.

BARNEY: Every day I’m a new fucking person. Yesterday I was crying. Today I’m happy. Okay, did you grow up in a predominantly white neighborhood?

HARRIS: I did.

BARNEY: So let’s say in the classroom of fifth grade, were you only Black person?

HARRIS: I was one of four.

BARNEY: Were the other Black people trying to coon with you? Were they trying to act white?

HARRIS: I don’t think that I knew I was cooning quite yet at that age. But it was really important for me to define myself, that I was not what you expected me to be based off of what you looked at.

BARNEY: The other Black kids, were they loud? Were they disrespectful?

HARRIS: No. They were just like me. They were good kids. I didn’t know them very well.

BARNEY: So how did you redefine your Blackness?

HARRIS: By speaking really well. That was one of my things. I went to a really good private elementary school and that’s where I started theater. I knew that I wanted people to take me seriously, and I knew my language was an entryway into being taken seriously. So if I held myself in a certain way and spoke a certain way, I would be taken seriously. That’s like micro-cooning. I don’t think I knew the meta layers of cooning that we got into later in life.

BARNEY: When did you realize you were Black? Did your family formally introduce you as a Black kid?

HARRIS: My parents weren’t radicals. My mom calls my dad an armchair radical. He would wear—

BARNEY: Kente cloth? Malcolm X raised-fist t-shirts?

HARRIS: He would wear a Che Guevara t-shirt.

BARNEY: What are some of the microaggressions or macro-aggressions that you face when you enter these white spaces as a Black artist? If that’s too big a question, how about today? Did any white people give you macro-aggressions? Was Interview magazine being a little weird?

HARRIS: We can out Interview on their own platform. I did tell them, I want more Black artists behind the scenes, and I felt like a coon for saying that.

BARNEY: Who did you tell? Was it a white person?

HARRIS: It was a white person. I asked for more Black talent on set.

BARNEY: Would you say that’s micro or macro?

HARRIS: Micro. They were like, “Oh, we understand the value of diversity, but—”

BARNEY: Stop being Black.

HARRIS: But there’s limited time to do this.

BARNEY: You’re lucky you’re even in this shit! And you brought a motherfucking crackhead bitch?

HARRIS: But they want you because you bring cultural capital and clout. How do you feel when Black people get upset about your performance?

BARNEY: I love it. Yesterday I was looking at Hannibal Buress and Eric André, and some white interviewer said, “This is what the people are saying on Twitter: ‘Eric André and Hannibal Buress are the two worst things that happened to Black people. And the third is slavery.’” I love that. I want to supersede that. I want to be the worst thing to happen to Black people.

HARRIS: Worse than slavery, worse than Eric André.

BARNEY: That’s what every Black person should aspire to.

HARRIS: Black people are often afraid of being the butt of a joke because of the legacies of trauma, and we purposely try to subvert that by making ourselves the butt of the joke.

BARNEY: I get in trouble as a “Black female.” Black men are outraged. They’re so mad that I fuck white guys. But that’s by default because Black guys won’t fuck me.

HARRIS: You’ll never catch me slipping, saying that I fuck white men on the record.

BARNEY: Oh bitch, you just said it. So I was going to tell you about a microaggression. This interview was slated for 4 p.m. and then the magazine messages me at 2 o’clock. They’re like, “We’re wrapping up. Can you hurry the fuck up?”

HARRIS: But that’s fashion people. They just want you to hurry, hurry, hurry. They make the schedule purposely tight.

BARNEY: I thought they were just trying to be like, “This bitch is going to be late. She’s going to be late and late and late.” Black people have a tendency that 4 o’clock actually means 5 o’clock for us.

HARRIS: You came on time.

BARNEY: Because they were rushing me.

HARRIS: That’s what white people are there to do.

BARNEY: Their culture is different. They like time. We don’t emphasize time.

HARRIS: It’s like a way of showing power. Time as a power structure, time is not real.

BARNEY: But time is money.

HARRIS: Time is money. And if they can weaponize our time, they can weaponize us. It’s a tool of domination.

BARNEY: I hate that shit. So it’s about monetization and capitalism. Okay. So there’s a bouncy house in back of you. Now tell us, is that related to cooning?

HARRIS: I think there’s some coons in this house. A bounce house is a temporary structure for Black people to practice failure. You can jump up and down in a safe space. You can try stuff. And it’s not as hard as the real floor because it’s forgiving.

BARNEY: I always tell people I like to fail good.

HARRIS: Our work is all about failure. We practice failure.

BARNEY: You’ll get pain, rejection, and the comedy’s very tragic.

HARRIS: Yes, that’s what the bounce house is about, failure. And me and Trevor [Bazile, a friend and collaborator] really dreamed about the bounce house. This became a joke between us. It was a subversion of the Capitol.

BARNEY: What capitol?

HARRIS: The Washington, D.C. Capitol.

BARNEY: Oh, I thought you meant white supremacy.

HARRIS: That part too. It’s very generous.

BARNEY: Is Interview mag a part of white supremacy? What do you think, Andy Warhol?

HARRIS: Inadvertently. Was Andy Warhol a white supremacist?

BARNEY: Yeah. What do you think? He had Basquiat. So he did gay Black guys.

HARRIS: But that was about positioning yourself next to Black people for—

BARNEY: Do you think Interview mag is doing that with us?

HARRIS: Yes. They’re positioning us well to have cultural capital.

BARNEY: But we seek that.

HARRIS: Exactly. That’s meta-cooning. It’s like we see that and still choose to engage.

BARNEY: Do you think we’re being exploited?

HARRIS: We’re being exploited right now.

BARNEY: Seriously? Thank god I have a blonde wig on.

HARRIS: They’re exploiting Barbara Walters for no money. But I say that this bounce house is like when someone dies. If you’re a wealthy person, when a family member dies, you inherit property. So much of how I talk about this story of the bounce house is that it’s like my inheritance from Trevor. With the money from the projects that he was working on we bought this house. And when he passed away, I inherited this house.

BARNEY: Oh, so you say this house is not a home.

HARRIS: That’s a Luther Vandross joke. And it is true. You get all this stuff, you get this house, we get this platform, but it always comes at cost.

BARNEY: What’s the cost?

HARRIS: Integrity. Because if we really were trying to do Black radical work, we wouldn’t be talking to this white magazine. I don’t think one can do Black radical work in this framework.

BARNEY: What other context would we use? I have a blonde wig on, and I like my blonde hair. You see, I have KKK colonizer inside me. So I feel like with me having long hair, I feel more beautiful.

HARRIS: Yeah, you have an obsession with beauty standards. What’s up with that?

BARNEY: Because I’m Nigerian and—

HARRIS: Nigerians have very strict standards of beauty.

BARNEY: So even the nose, we’ll be like, you have a broad nose—

HARRIS: Would you ever get plastic surgery?

BARNEY: I would get a face-lift. Sometimes I look at Jane Fonda and I’ll get jealous.

HARRIS: Is that going to be the tail end of your career, going super plastic?

BARNEY: I would like to get triple-D or triple-Z titties.

HARRIS: Should we use this platform to start your GoFundMe for your new titties?

BARNEY: And an old white boyfriend in a wheelchair. And I wheel around with him in the mall. I want everyone to look at us and be like, “Oh my god, she’s such a Black slut.” And I’ll be like, “That’s so true.”

HARRIS: You like to play both sides. You want to be Black and you want to be white.

BARNEY: Exactly. Leave me alone. Okay, so let’s talk about Trevor. Trevor was a big believer, a talented artist. We all met in 2021, right?

HARRIS: The three of us met in 2021, but I met Trevor in high school. We grew up in different neighborhoods, but we went to an arts high school in Miami that you had to audition to get into. And Trevor auditioned for jazz. He was a jazz saxophonist, and I was in the theater department.

BARNEY: What was the encounter between you two?

HARRIS: We used to party in the same circles in high school and we had a similar friend group. But we weren’t that close then. It wasn’t until he wanted to make a movie about Charles Mingus, the jazz musician. He has an album called The Clown, and Trevor knew that I was doing a lot of work with clowning, so he wanted me to play the black – face clown that would lead his Charles Mingus movie in 2019. That’s when we got really close and started hanging out.

BARNEY: When you say blackface, did you make your face darker? I did that.

HARRIS: This is an ontological question. Can a Black person do blackface?

BARNEY: I did. It was a couple years ago. I was on the train, and I even played minstrel music and everyone was like, “Oh my god, she’s in blackface, but she’s Black.”

HARRIS: That’s an oxymoron. But yeah, Trevor was my best friend and he passed away in 2021. It’s really sad. So much of this chapter of the work is about honoring him and his legacy. He inspired so much of what we’re doing today.

BARNEY: I’m so honored that Trevor wanted to meet me.

HARRIS: You were our superstar. When Trevor got here in 2021, we were working on the film festival. All we knew was that we had to work with Barney. Trevor was a meme kid and an internet kid just like you. All triggers, no warning.

BARNEY: He kept reposting my videos, and I thought it was a white kid in a fucking basement. Loser, trash. And he’s like, “I’m behind it.” I’m like, “Oh my god.”

HARRIS: He was doing digital whiteface. He was performing as a sort of white incel online.

BARNEY: You know what inspired me about both of you? You guys were so young and took over these sophisticated corporate spaces. Trev – or put together this big festival that was funded by Peter Thiel?

HARRIS: There was some Peter Thiel money rumor, allegedly.

BARNEY: What would you tell your 18-year-old self if you could do it all over again?

HARRIS: I think I played my cards pretty right. I would tell my 18-yearold self to keep going.

BARNEY: You don’t think that you should have taken more risk or less risk?

HARRIS: I don’t want to sound too privileged, but I do feel really happy with a lot of the cards that I played.

BARNEY: You do get every grant.

HARRIS: I’m good at grant writing. I’m the token pick of the year.

BARNEY: So what else is going in this show?

HARRIS: It’s about dancing alongside my inheritance from my best friend. It’s about improvisation. Formally the work is about the act of improvising itself.

BARNEY: Do you have a shrine of Trevor?

HARRIS: I think the set that we’re sitting in is a shrine of Trevor, the paintings. He wanted to see a huge painting of George Floyd. That’s why we made a painting of George Floyd.

BARNEY: When he died, you guys had just done a show together.

HARRIS: We did a performance in a skate park where I tried to inflate the bounce house with my mouth over six hours on livestream, and Trevor orchestrated a jazz band around me. That was one of our biggest dreams to come true. To do a big opera, a big performance, that was multiple hours. And we did that. That was the last day I saw him.

BARNEY: Have you ever been called the N-word by a white person that you were having sex with?

HARRIS: Surprisingly, no.

BARNEY: Oh. But you want to make them mad enough for them to call you the N-word?

HARRIS: I mean, that would be interesting if it was organic. But if we’re going to do a role-play, that’s less interesting to me.

BARNEY: Do you want to be auctioned off or beaten or whipped?

HARRIS: When I graduated from acting school as an undergrad, we had to do an acting showcase for agents and casting directors. That felt very much like the auction block. It felt like you were getting put up to be bought and sold by casting directors and agents. That was the worst experience in my life.

BARNEY: You felt more exploited there than here?

HARRIS: At least I get to take pretty pictures today. So that’s a better form of exploitation. Sometimes I fear that I exploit you. Do you feel exploited by me?

BARNEY: No. You’re very supportive. But you probably want clout. That’s okay. I also want to be exploited. I remember I would go up to white people and be like, “Can you exploit me please?” That’s how I got my old editor.

HARRIS: But Barney, let me read your contracts before you sign them. I’m afraid that someone’s going to actually exploit you one day.

BARNEY: Because I’m so needy for attention.

HARRIS: Well, not necessarily because of that, but just contracts get weird. And yes, we want to be exploited, but we want to own the rights to our content, too.

BARNEY: Do you think that I exploit myself by calling myself a crackhead and then doing all those videos?

HARRIS: No, that’s just art.

BARNEY: How much do you feel like you have to code-switch in these white spaces?

HARRIS: I code-switch a lot less these days. I’m trying to work really hard on that, showing up in all these spaces as I am. No matter what space, you get the same Nile. But you were talking about that the other day, about feeling angry and acting on it because life is too complicated to not; why not? And I don’t really give myself space to be angry.

BARNEY: Were you angry about Interview magazine today? Did you feel like you had to code? Did you code-switch any?

HARRIS: No. The emailing leading up to the shoot, I was doing some code-switching. But once I showed up I felt pretty honest.

BARNEY: Can’t they put you on the cover? Niles Harris, Cooning into the Metaverse.

HARRIS: But I’m just a minor performance artist.

BARNEY: We’re outsider artists. If I were in charge I’d put us on the cover.

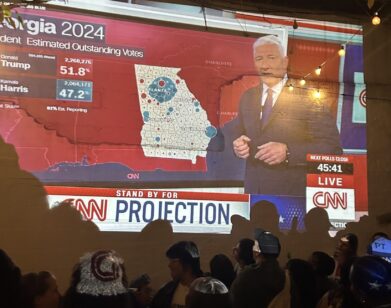

HARRIS: Okay. 2024 Crackhead Barney runs Interview magazine.

BARNEY: No, because I’m running for president 2024. But I guess this interview’s dedicated to Trevor Bazile.

HARRIS: Yes, that’s right. This feature is dedicated to Trevor Bazile.

___

Grooming: HIDE SUZUKI using ORIBE.

Set Design: DYER RHOADS.

Fashion Assistant: LULU LEE.

Location: ABRONS ARTS CENTER.