Neke Carson Painted Andy Warhol With His Ass, Then Founded a Modeling Agency

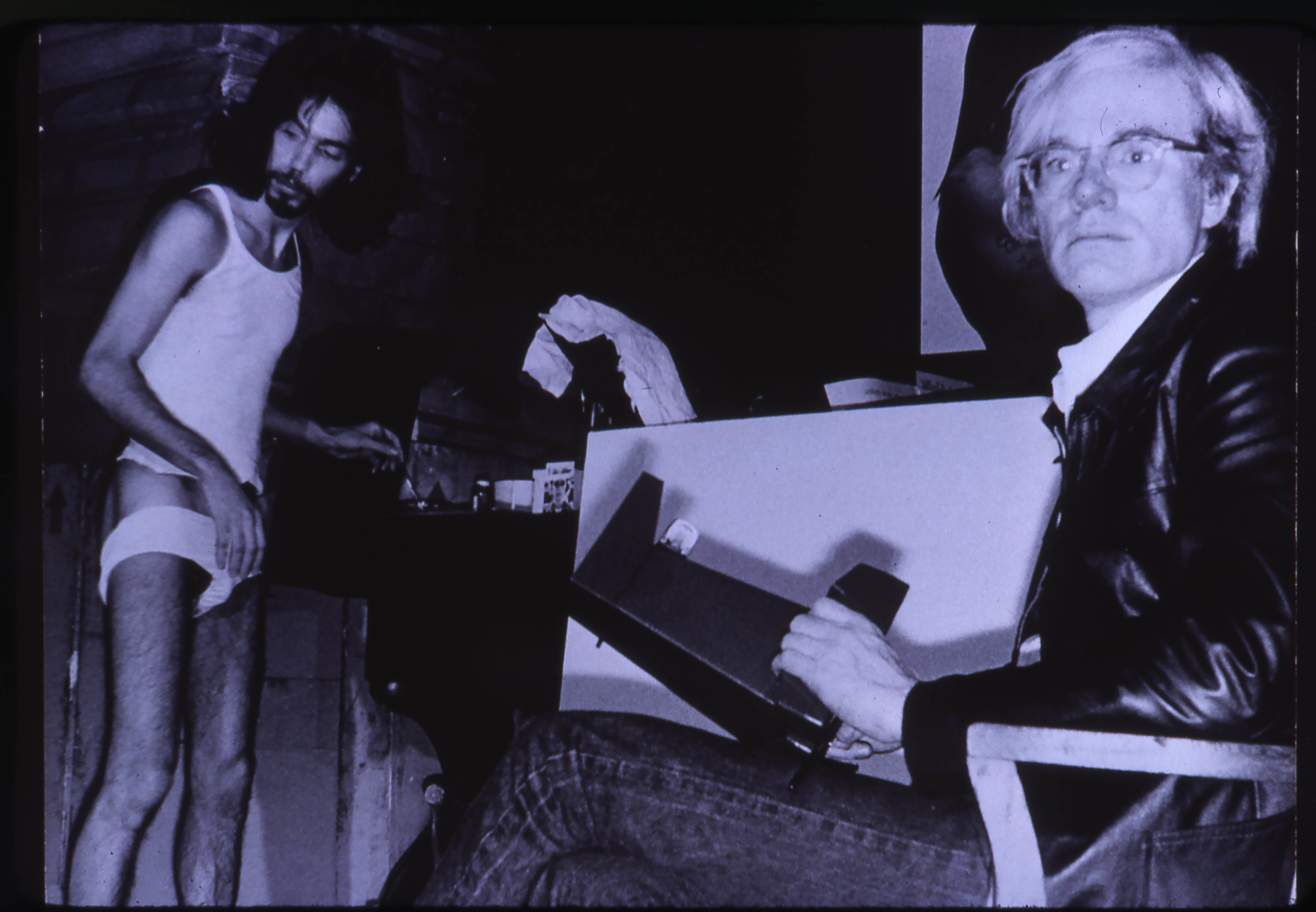

Neke Carson paints Andy Warhol (documentation of portrait session at the Factory). Photo by Anton Perich, 1972.

I was casting artists for a group show titled “Comedy of Erros” when Christopher Schwartz, the gallery director I was working with, forwarded me Neke Carson’s portfolio. Within the mix of drawings, photographs, newspaper clippings, flyers, books, and sculpture, the most compelling pieces for my purposes were a 1987 sculpture of a black satin pillow creased and indented as if kneeled on, and a series of 1969-1972 drawings of inventions, such as a trampoline stretched from twelve hanged humans and miniskirts made out of presidential scalps.

“Comedy of Erros” is “presented” by “Pillow Talk,” a community event I’ve put on for over two years in Los Angeles and New York. Mingling peer-to-peer group therapy with a think tank and a party, Pillow Talk explores the intersections of sex, love, community, and communication from the privacy of hotel suites and apartments. The series services art and art-adjacent people, so it was natural for a gallery opportunity to arise. Unfortunately, Carson’s Kneeling Pillow Sculpture is unavailable, but we have confirmed three of his incredible drawings. In one, called The War Between the Clean and Dirty People (1971), a gang of slime covered pin-ups battle similar but spotless figures who wield hoses, wearing shower heads as halos. In another, a beam of rain cascades like god’s spotlight, falling onto a reclined cross with almond eyes, a shower cap, and a garter belt. “The rain has just started,” the drawing reads. There’s more writing on it, which Carson explained is meant to be the “cross-dressing cross” singing: “O yes it’s great to be out here oh come on rain come on rain do it again touch all of me come inside…”

Born in Dallas, Texas, in 1946, Carson lived in the New York that magazines today are nostalgic for. He was a Factory regular and a New Waver and a post-9/11 community arts programmer. For fifteen years, up until a few years ago when he moved to Sag Harbor, Carson ran Tuesday and Thursday-night performance events out of the Gershwin Hotel, where Poet Laureates shared the stage with pop stars, fine artists, film actors, opera singers, and kink performers.

“Comedy of Erros” was supposed to open on April Fools Day at The Gallery @ El Centro off the Hollywood Walk of Fame. We’ll install it when we’re given the collective green light. In the meantime, we have this conversation, which surveys Carson’s comedic art canon, his famous portrait of Andy Warhol painted with his asshole, and his new wave modeling agency that cast the 1982 film, Liquid Sky.

———

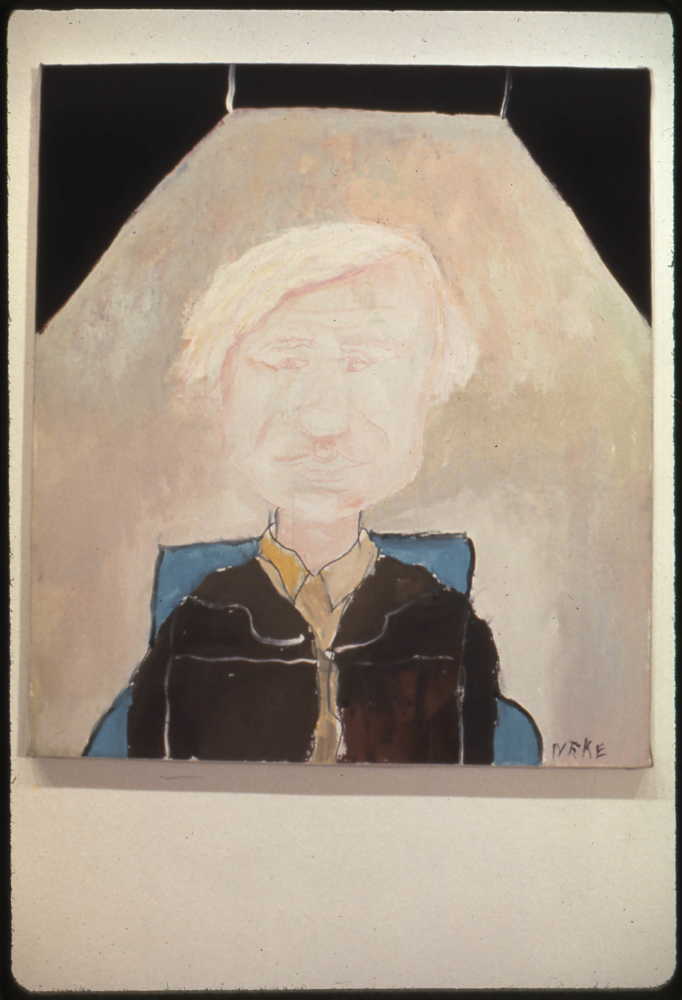

Neke Carson, “Portrait of Andy Warhol,” 19×24 acrylic on canvas, 1972.

FIONA ALISON DUNCAN: How did the [Andy Warhol] portrait come about?

NEKE CARSON: By 1970 or ’71, there were three people I would visit at Union Square. The first was Jean-Paul Goude, the photographer and image-maker who would later marry Grace Jones. He was in one penthouse. A couple of houses down was Antonio Lopez, an incredible fashion illustrator. Absolutely fabulous. And at the end was Andy on the corner. When I did a show at the Warhol Museum in 2008, all these young people who worked there were totally amazed that I knew Andy. To me the question was: in New York at the time, who didn’t know Andy? He was available to creative people who could get his ear and make him laugh. I would go to the Factory pretty regularly. In a conversation with Andy I said, “I’m doing this thing called rectal realism where I paint with a brush in my butt and I would love to do your portrait.” He said fine, let’s do it. Glenn O’Brien and Vincent Fremont filmed it. Anton Perich took pictures. The process is very difficult. It’s your eye-ass coordination. You’re looking through your legs, you’re looking up at the face.

DUNCAN: Did you do yoga or anything?

CARSON: No. At the time I was playing basketball so I was somewhat agile. A doctor gave me some pills for my back because it’s hard on the back. I really wanted to capture my subjects. I could’ve just done a smiley face and everyone would’ve laughed and gone home, but I wanted to capture Andy. I got to stare at his face for a long time. When I finished, it looked like him. No one was expecting that. I had used whiteout for part of his skin. Over the years it faded, and now it has a very ghostly feel to it.

DUNCAN: Had you practiced much?

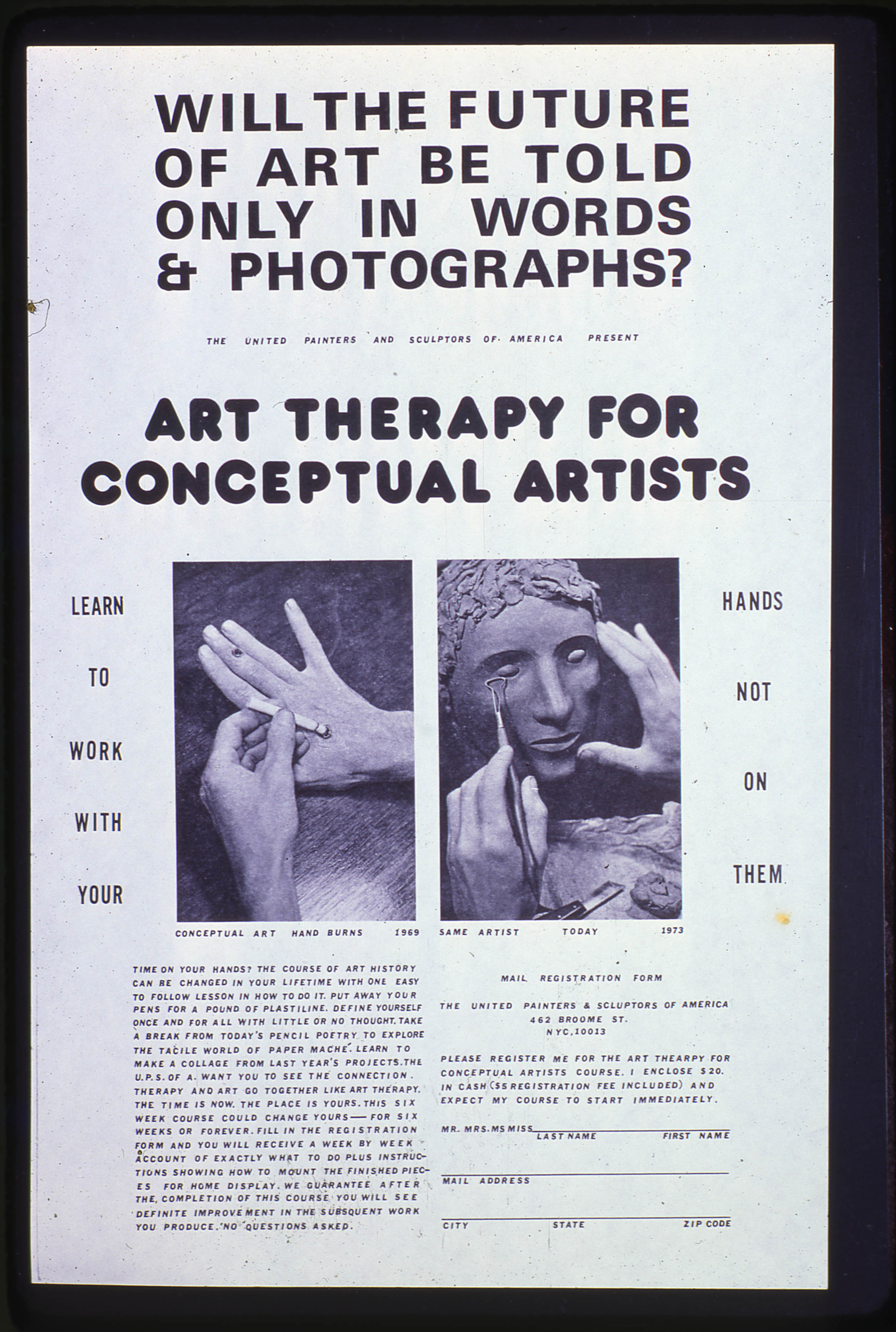

CARSON: This was probably my third painting and I was improving with each one. Later I did Fred Flintstone. Then I did a half-assed painting which was half with my hand, half with my ass. It was a mark of Zorro, five feet by six feet. This was a time when artists were doing things with their body. Body mutilation or whatever. Things were getting a little out of hand. I did a self help book called Art Therapy for Conceptual Artists in order to calm things down, with activities like papier-mâché crocodiles or making big wooden spoons.

I don’t know if you know this history, but the Andy portrait was stolen. It was in a punk arts show in Washington, D.C. and Edith Massey, who is connected with John Waters, was singing and performing upstairs, and some kid went downstairs to the gallery room and took my painting home.

Neke Carson, Art Therapy for Conceptual Artists poster for Six Week Therapy Course, offset printed on paper, 1973.

DUNCAN: How did you get it back?

CARSON: The gallery people were really upset. They contacted a bunch of radio stations and eventually began a dialogue with the perpetrator. They pleaded with him to bring it back, saying there will be no repercussion. Meanwhile, the police were talking to me saying, “We’ll arrange to meet him in a park and jump him.” I refused to allow that to happen. I didn’t want my painting ruined. Eventually, the guy who ran the gallery and the people on the radio just convinced him to come in. I came up from New York, did a little drawing of the piece, gave him that, and he gave me the painting.

DUNCAN: How did you feel through this process?

CARSON: Like I’d just been kneecapped.

DUNCAN: Did they take anything else?

CARSON: No, just that one.

DUNCAN: How did you meet Jean-Paul Goude?

CARSON: He was art directing Esquire. My brother Kit got me a “go see” with him. I started showing him pieces I did like “Dead Birds Fly Again,” where I took a dead bird, put a wire around its neck, and connected the wire to a motor so the dead bird could fly again. I was showing him mainly blueprints of my pieces. I was in Esquire twice through Jean-Paul. Once was for this “Art of Evil” issue. I never did work on evil, but I did do stuff that involved blood. I did a chair that pumped blood, and made a cross filled with blood that said, “Bite me and drink what you love,” for vampires to destroy themselves. With Esquire, I did a bleeding ice skater. I put a needle on the end of a skate blade that connected to a tube with blood and valves that I could push. It makes a trail of blood on the ice as you skate. Jean-Paul arranged that we do this at Rockefeller Center. They closed off the whole rink for us on a Saturday morning. I had never skated before in my life. They pushed me out into the middle of this rink with my apparatus and I just stood there. Everybody was yelling at me to do something. I was almost falling over.

DUNCAN: Was it human blood?

CARSON: No. I deal in fake blood. I had gone down to the Meatpacking District to ask for some butcher’s blood. It just happened that President Johnson was in town that day and they were like, “You aren’t going to throw this at the President, are you?” I looked like the type who would. I took the animal blood home and tried it out but I didn’t like it that much, aesthetically. I found a chemist who worked on fake blood. He was my hookup. I remember people being scared of the blood pieces. I could feel fear. Now, just about anything is accepted, but back then, there were more rules.

DUNCAN: Were you trying to break rules?

CARSON: I was just doing my work. Art is like a taffy pull. The job of an artist is to pull as much as possible. I just thought I’m pulling. I thought that was good.

DUNCAN: What about your Suicide Egg piece?

CARSON: Another invention. I thought of myself at that point as an inventor more than an artist. The Suicide Egg is very lightweight. It hooks on your back and you climb up to a high spot on a building and you get inside the egg and you crack it open and are born a splat on the Earth. This is one of these things that scared people. I’m just combining opposites. Life and death.

DUNCAN: Your latest body of work is also about opposites: light and shadow. Could you talk about this series and the experience of making art from home?

CARSON: Light used to come in my room in the morning and wake me up. As it traveled around the room I began to take pictures of its path. Eventually I would make a tableau of fabric that would be illuminated by the light. I became a light paparazzi. I even made a little red carpet. The morning light became my biggest star.

DUNCAN: Some of the motifs in your earlier work feel very Catholic, like The War Between Clean and Dirty People—shame and filth and the shower heads as halos. Were you raised religious?

CARSON: I grew up Catholic. I’m now Buddhist. My brother Kit went on to be a Jesuit priest.

DUNCAN: I was reading a biography of the brothers Carson and it’s like a movie. Was this the filmmaker brother? [L. M. Kit Carson, who co-wrote the screenplay for Paris, Texas, based on the novel Motel Chronicles by Sam Shepherd.]

CARSON: Yes, but that didn’t last long. The discipline involved was too much. Religion played a part. My other brother Goat became a reverend. He was a musician. He won a Grammy for writing a song with Dr. John.

DUNCAN: How did you start doing events at the Gershwin Hotel and what did that site mean to you? The exterior design is incredible.

CARSON: The Gershwin was a very creative place. I found a lot of people from the old Warhol days there. It was a scene. I started doing events there with the actor Michael Wiener and the pianist Vicky Chow, and opera with Jennifer Peterson. We did events there for fifteen years. We started on Tuesdays. That’s the Evening of Enlightenment. When you listen to gospel music, “one Tuesday evening” is when the person found god. Also, 9/11 was on a Tuesday. We wanted to take back Tuesdays. It was a way of transcending the tragedy. The event was called “Live from the Gershwin.” We did operas in the lobby, Handel’s Rodrigo and Kurt Weill’s complete songbook in chronological order. Debbie Harry read her poetry. We had Billy Collins, the poet. There were people being hung by hooks. Then we’d have somebody like Jared Harris, Richard Harris’s son. He came with his brother Jamie. They did a memorial to their father, a bottle was passed around. The message to our performers was, “We will let you set the bar as high as you want to set it, you can do whatever you want to do.” It gave people an opportunity to do things they didn’t usually do.

DUNCAN: I want to talk about your 1980s modeling agency, LaRocka. What was the scouting and casting process like? Was it an excuse to meet people?

CARSON: It was a lot of things. In the years before, I had gone to the racetrack to become a jockey. I wanted to win a race and have all these drawings on my back and then have a show called “Win a Place to Show.” I spent two or three years at the racetracks in Florida and Atlantic City. It was an exciting adventure, but also really dangerous. I realized it’s one thing for me to play basketball at the Evangeline residence and quite another go out on a horse, even though I grew up around horses. Quarter horses and racehorses are like a truck and a Maserati—two different things. When I got back to New York, I could see this music scene was happening. I was going out every night. I decided to organize it a little bit. I had broken up with my wife. The next thing I’m doing is starting a modeling agency.

DUNCAN: To meet new wives?

CARSON: To meet the new scene. It’s a wonderful thing to go into a club and ask someone who you find very interesting, “Would you like to join my organization?” These people were very talented. Anne Carlyle, one of our models, co-wrote Liquid Sky with the director Slava Zuckerman and also played the male and female lead. Most of our models were in Liquid Sky. It was a rebirth of music and style. Our agency did things for Parco, a department store in Japan. Also Radio Shack. We were the agency if you needed that kind of look.

DUNCAN: What look?

CARSON: At the time they were calling it new Wave. Very sharp. It was a reaction against disco. It was Blondie and people like that, redefining what looks hip. If the punks were the beatniks of that era, New Wave was more like what came after. The attitude was different. There was no angst and anxiety. It was fun to be crazy.

DUNCAN: Did the New Wave embrace fashion and commerce in their art and music? You seem to have with a lot of your work.

CARSON: Yeah. It wasn’t a sin to them. The attitude was: I can make a lot of money doing very clever stuff and that’s fine. You didn’t sell out because there was nothing to sell out—that’s how you got started.

Neke Carson, “Atomic Bicycle,” 72x42x74. Photo by Jean-Paul Goude, 1970