ART!

Jack Brusca: Forgotten by the Art World, Until Now

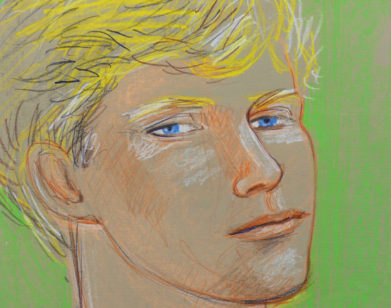

26th and 6th, 1992

In today’s age of ultra-visibility, it’s hard to imagine a Google search for an artist’s name yielding anything less than a page’s worth of search results—but such is the case for Jack Brusca. Born in 1939, Brusca rose to prominence in New York City’s fringe art circuit in the 1970s after staging his first solo show at the (now closed) Bonino Galleria in SoHo. It wasn’t long before Brusca’s paintings, known for their lush surrealism and sensual figurative work, made their way into the mainstream—appearing in the Whitney Museum’s collection and making the exhibition rounds at several esteemed institutions and galleries around the city.

Given the artist’s notoriety in downtown circles, his departure from the contemporary art conversation over the last few decades is a mystifying one. When Brusca passed away from AIDS-related complications in 1993—four years after his final solo show at SoHo’s Paraty Gallery—he left a rich archive of paintings and drawings in his wake, but they remained inaccessible to the public. This month, however, the curator Daniel Cooney has unearthed Brusca’s unseen works, on loan from the artist’s brothers, in a new exhibition at his eponymous gallery titled “Jack Brusca Paintings 1975-1993.” The show spotlights 10 of the late artist’s most notable paintings—from Self Portrait In Hospital Bed With Angels to Night Work—which have resided for the past 28 years in a Long Island storage unit. To mark the opening of the new exhibition, Cooney spoke to Interview about his first encounter with Brusca’s work, New York-centric nudes, and the feeling of bringing a great talent’s work to light after all these years.

———

JULIANA UKIOMOGBE: When did you first encounter Jack Brusca’s work?

DANIEL COONEY: About a year ago. I was looking at the Visual AIDS website. They have a database of artists that have either died of AIDS or are currently living with HIV. It’s a pretty extensive archive, and I came across Jack’s work there. There’s not much information about Jack on the website, and they also didn’t have any contact information for next of kin or an estate. So, of course, the next step was Google. I found his obituary from the New York Times. On Instagram, I did a deep-dive, and finally decided to reach out to someone named Ken Brusca, who turned out to be his brother. Through him, I started learning about Jack’s work. That’s how I got to go to Long Island to see it in person.

UKIOMOGBE: How many pieces of Jack’s work did his brother have?

COONEY: 25 or 30. They’re in a storage unit and have been sitting there for a very long time.

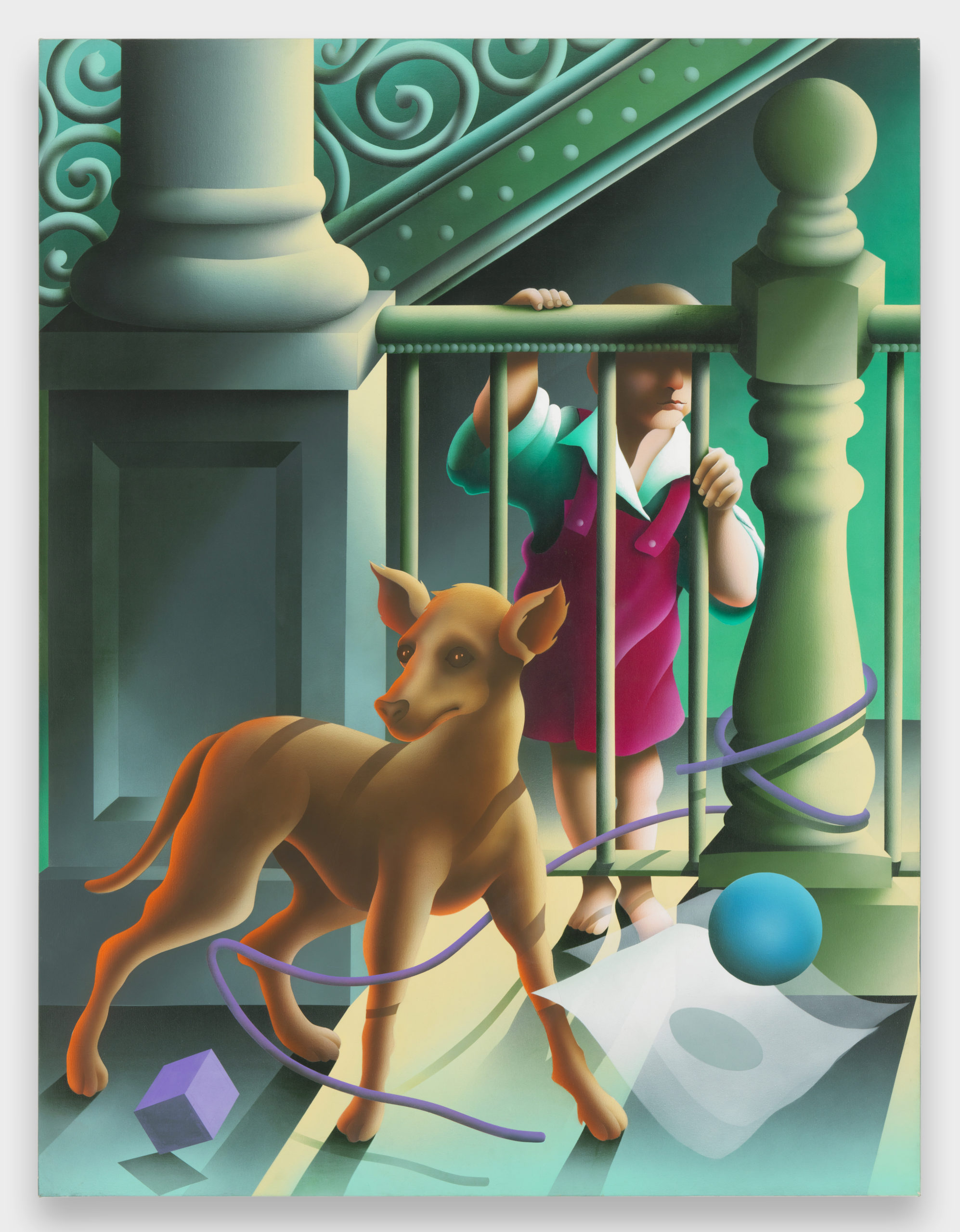

- The Pool, 1975

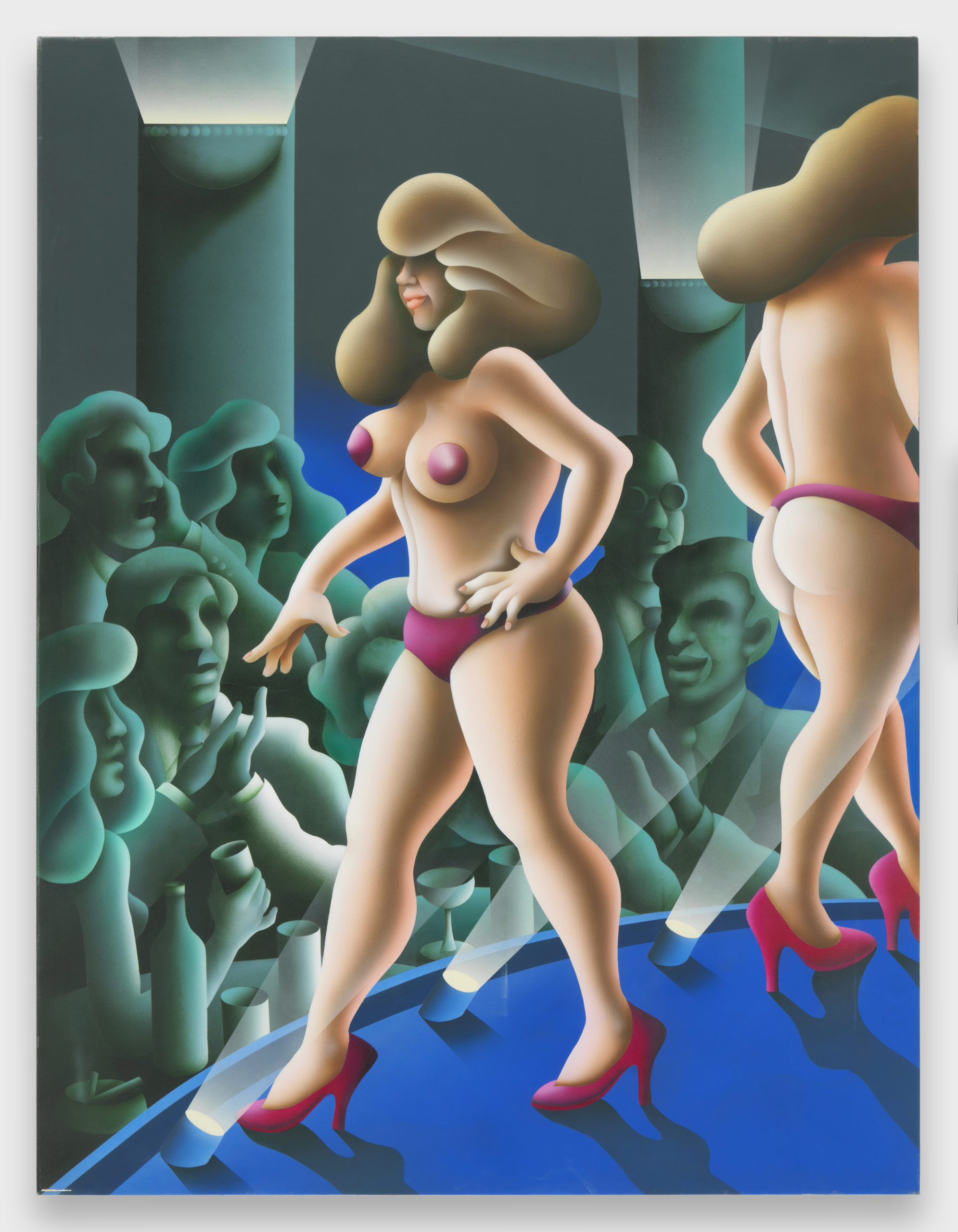

- The Dance, 1975

UKIOMOGBE: Why do you think his work slipped under the rug?

COONEY: That’s a good question. I think that a lot of people who died of AIDS were traumatized, and they didn’t plan their estates properly. A lot of them were in their 20s and 30s, sometimes even younger. Jack was 54 when he died. Although he was a bit older, that doesn’t mean that he was more prepared to die unexpectedly. He left his work to his family, and they have their own lives, too. Promoting someone’s work after they’ve died is a full-time job. For the family, it’s sometimes very traumatic. Keeping it safe is an act of bravery in itself. Even if the family doesn’t advance the career of the person, at least they’re holding onto it. A lot of people who died of AIDS had families who were ashamed of them. Their work would just end up out on a street corner in the trash.

UKIOMOGBE: Was his family apprehensive about letting go of his art after holding onto it for so long?

COONEY: They didn’t express any apprehension to me, although I’m sure after years of not really dealing with it, when I reached out to them they were probably like, “Well, who is this guy?” But I have a track record of doing this type of work, and many times it’s successful. Ultimately, they were grateful that I’m doing the show. It’s a beautiful tribute to Jack’s life.

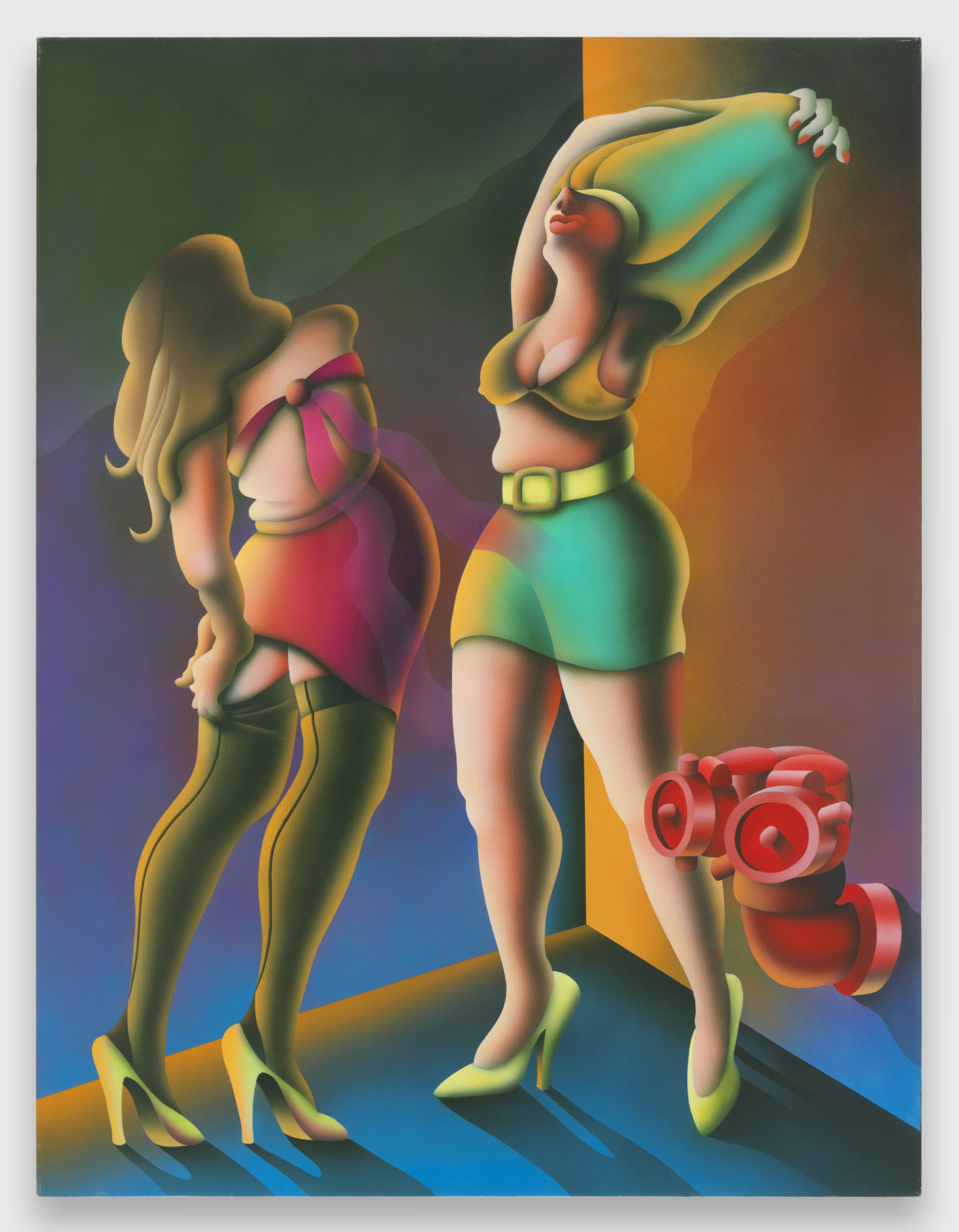

- Copa Girls, 1990

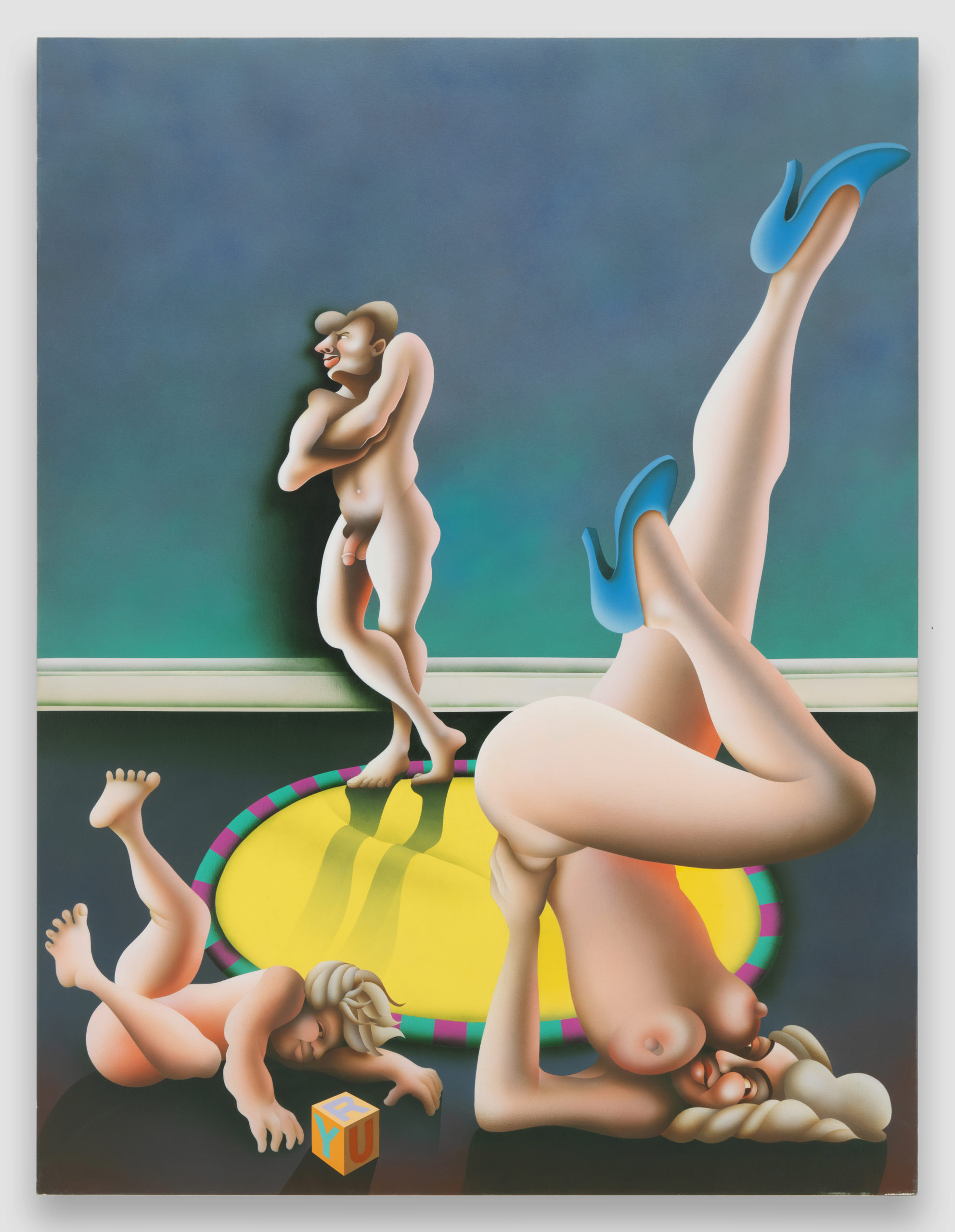

- Family, 1990

UKIOMOGBE: Definitely, I agree. How did you curate the show?

COONEY: If you break it down, there’s figurative work, there are abstractions, and architectural work. There are only 10 pieces in the show, which is really the maximum that I could exhibit in my space.

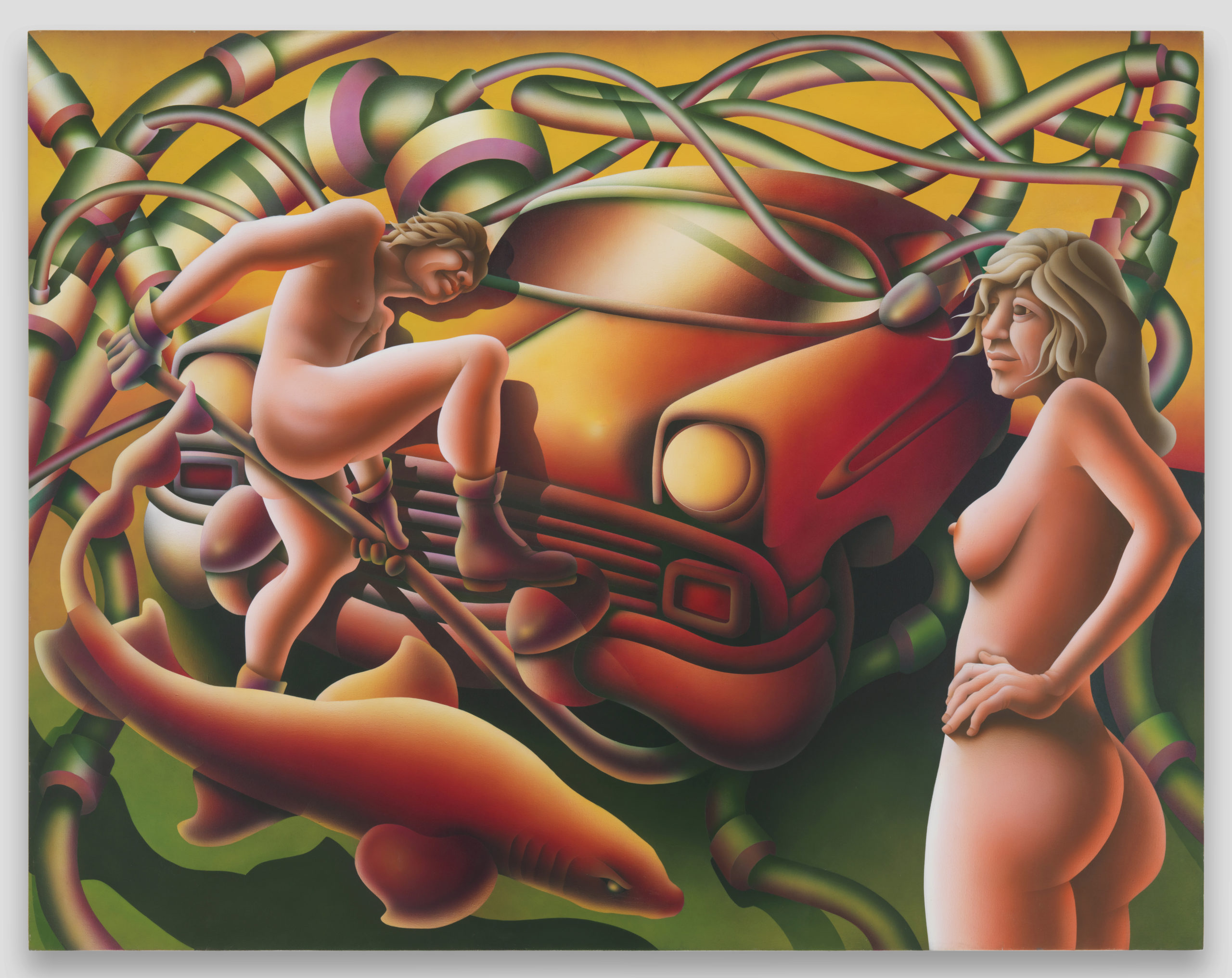

UKIOMOGBE: I love the nude pictures. They’re so fun and quirky.

COONEY: Yeah, they’re figurative, but they’re very New York. They’re very much about these dirty little corners—the subway, the strip club, hookers, the hallway of a tenement building. A lot of the work I show is very New York-centric and very ‘70s and ‘80s. So it fits right into the bigger picture of the gallery.

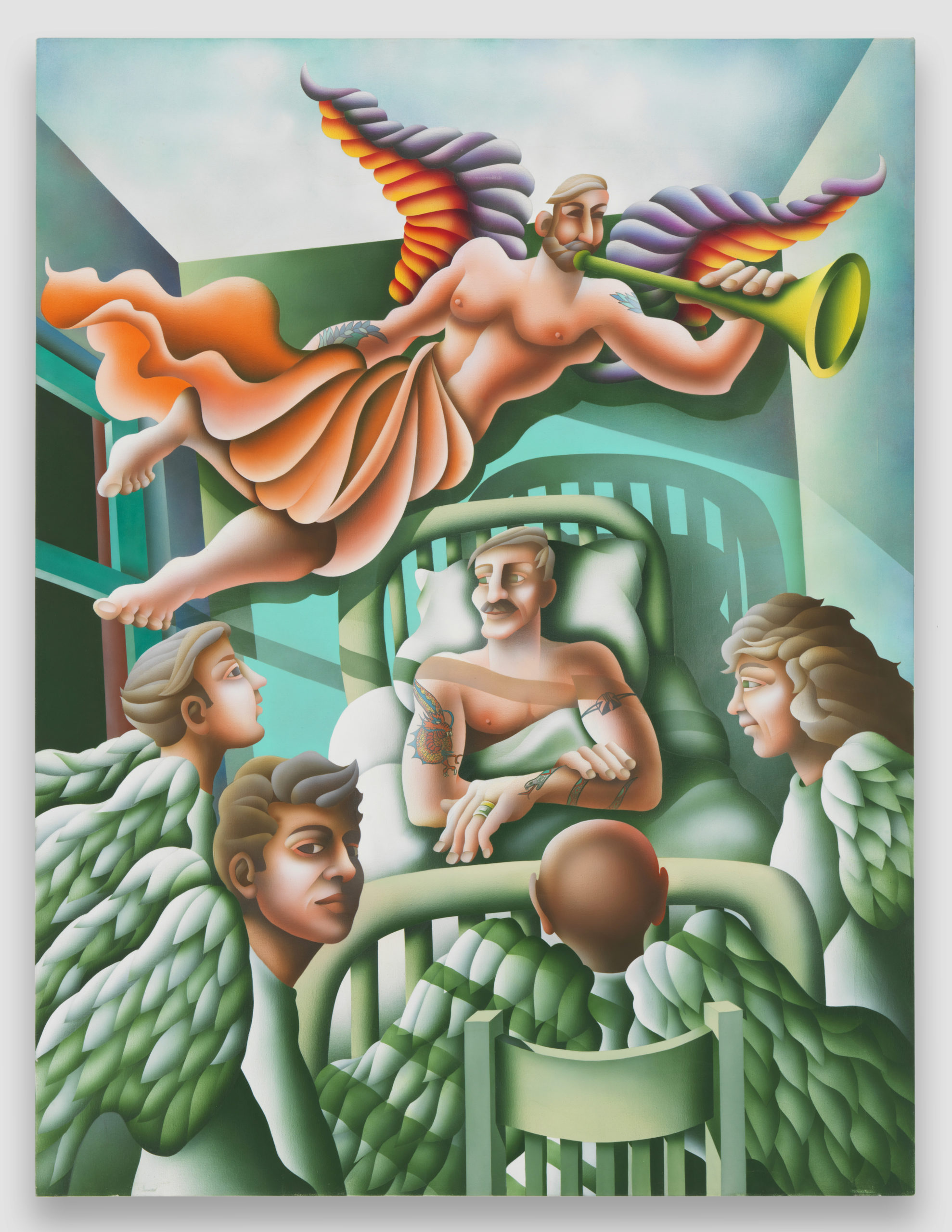

Self Portrait In Hospital Bed With Angels, 1993

UKIOMOGBE: Do you have a personal favorite of Jack’s paintings that appears in the show?

COONEY: Yeah, I think it’s the most poignant piece—Self Portrait In Hospital Bed With Angels. It’s from the year that he died and it’s a portrait of him in a hospital bed surrounded by angels who are friends of his that died before him. It’s heartbreaking, but at the same time, there’s joy to it. He looks good, strong, he’s got this big mustache, he’s got tattoos. He pictures himself as very muscular, which, I imagine at the end of his life, he probably wasn’t. But as far as self-portraits go, it’s a very flattering portrait of himself and then he has his very good friend Frank Diaz flying above him with these colorful angel wings blowing a trumpet. And the light is coming in and he’s looking out the window. There’s something really beautiful and tragic about it.

UKIOMOGBE: What has the reception to the show been like? Are you finding that these are new fans of his or older fans that maybe forgot about his work and are returning to it?

COONEY: There are a handful of people that, as you said, are returning to it. But I think the majority of people are new and have never heard of him before.

- Night Work, 1990

- Summer In The City, 1990

UKIOMOGBE: That’s great that you’re introducing a whole new audience to his work.

COONEY: That’s what I was hoping for. I also expected that. A lot of people of that generation are no longer here. There is a whole new generation of young gay artists that are doing figurative work now, and a lot of it is very similar. If you look at Justin Liam O’Brien or Louis Fratino, there are elements of Jack’s work in theirs. I think they probably don’t even know who Jack was. And certainly, Jack wasn’t the first person to paint in the style either, but it’s a generational thing. So that’s what really piqued my interest. I made sure that the title of the show had the dates of the work—1975 to 1993—because I was pretty sure that people would think it was a contemporary painter. They look like they could’ve been done this year.

UKIOMOGBE: That’s so true. Did you discover anything new or surprising about Jack while you were unearthing his work?

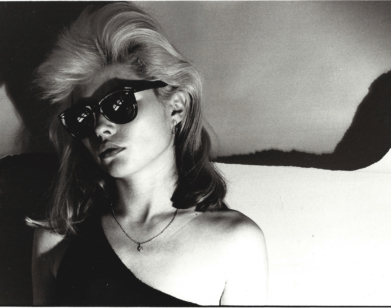

COONEY: I’m still very much learning about Jack. You know, a couple of years ago I did a show by an artist named Tim Greathouse. As people came into the gallery, I asked if they knew of him and they’d be like, “Yeah, oh my god I love him” and they’d tell stories. And then I’d ask those people if they knew Jack and no one did. I guess he just ran with a different crowd. It doesn’t seem like he was part of the East Village scene. It seems that he was at the gay clubs and going out. He was definitely on the scene at Fire Island, and he painted the first logo for the Fire Island Pavilion, which is the dance club out there. He painted the wall murals there when it first opened. At that time, without cell phones or Instagram, people could be in the Chelsea scene and not know people in the East Village scene. I do know that Jack’s roommate was Frank Diaz, who was a model and muse for [the photographer] Robert Mapplethorpe. I don’t want to say that I didn’t learn anything about Jack—it’s more that I’m still in the discovery period.

UKIOMOGBE: It’s an evolving process.

COONEY: Absolutely.

———

Manhattan, 1991

———

The show will run at Daniel Cooney Fine Art through December 18.