STUDIO VISIT

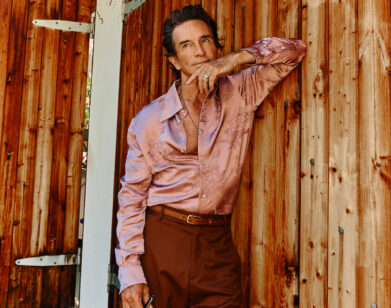

“I’m a Beatnik, Too”: Hannah Beerman, in Conversation with Eileen Myles

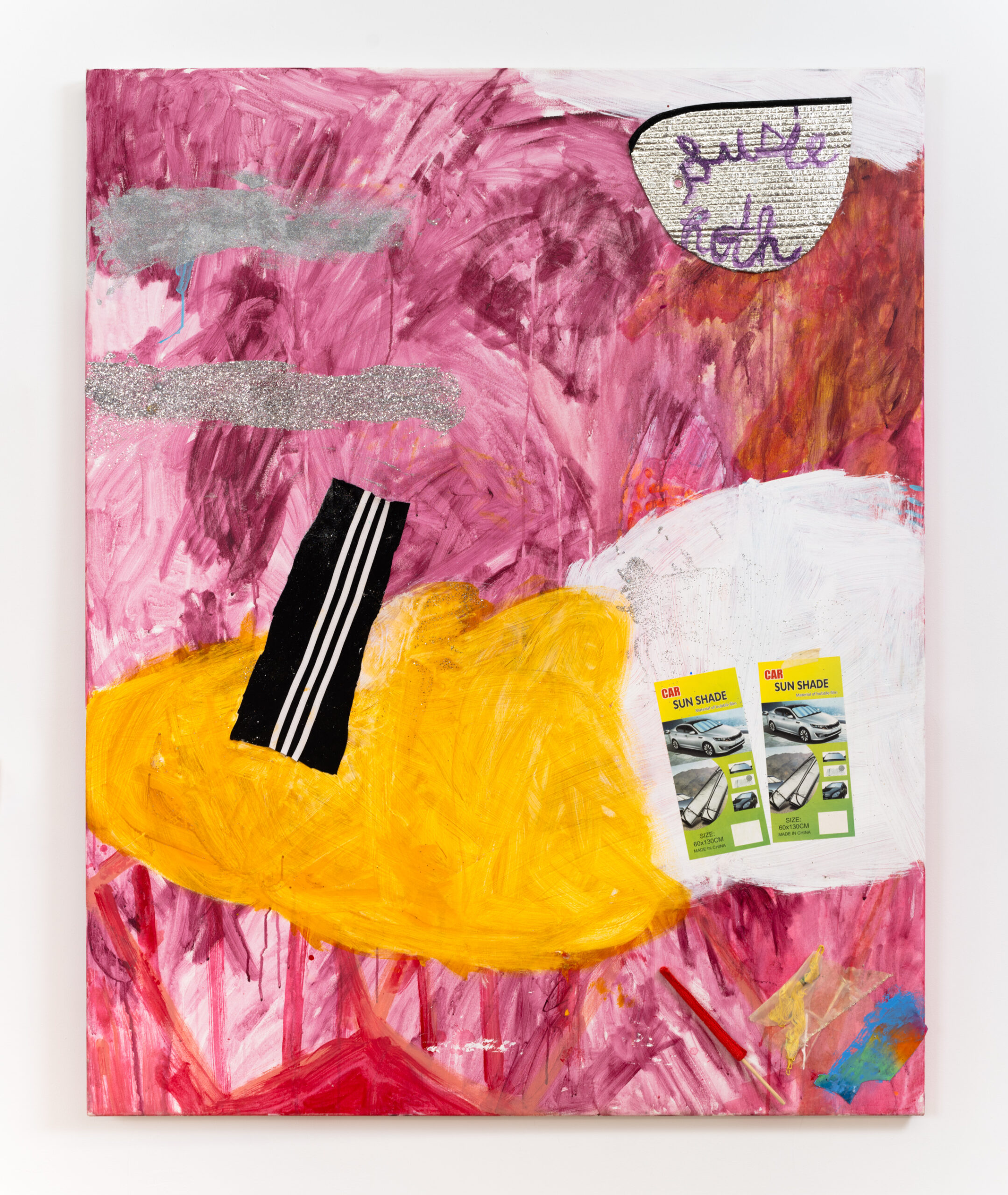

It takes a formidable and imaginative painter to inspire a work of original poetry by the great Eileen Myles. But Hannah Beerman’s assemblage paintings, in which great bursts of color and texture sit—and whip and clang and rattle and jingle—alongside found objects oftentimes unearthed among the purposeful clutter of the artist’s studio, demands this kind of close reading and consideration. “These are delightful and these are macabre,” goes the poem Myles wrote for Beerman, their one-time neighbor and now friend, before the opening of a new exhibition of her paintings at Kapp Kapp gallery downtown. “That’s absolutely part of why I love you and your work, cause you’re a beatnik,” Myles explained. “I’m a beatnik, too.” On Zoom, as the poet made a cup of green tea, the two artists got together to discuss the virtues of mess, the work of Diane di Prima, and saying goodbye to Diet Coke.

———

HANNAH BEERMAN: Are you making your green tea?

EILEEN MYLES: Yeah, I totally am. I just walked in the door, so I had to get the operation going.

BEERMAN: Where are you coming from?

MYLES: I went to the gym. I was sort of waking up in a particularly slothful way, I just looked at the time, and I thought, “Go now.”

BEERMAN: I miss being your neighbor. I miss when I could just text you and we could just meet up all the time.

MYLES: I know, and I always think of you as my neighbor, which is so funny, cause I think of us meeting as being a neighborly process.

BEERMAN: Yeah.

MYLES: It happened on social media because you posted your studio. I was like, “This person lives like me.”

BEERMAN: Yeah. Well, I have a huge crush on your apartment, as you know. I think it’s the most romantic place in New York City.

MYLES: Well, thank you.

BEERMAN: I really loved this poem that you sent me last night. Pretty special thing.

MYLES: That’s really great. I was thinking about your dog, cause we both have dogs, and my dog is Honey and your dog is Jupiter. And Jupiter is where and how we meet, because Jupiter is jovian, it’s the jovian planet of expansion, and that’s exactly how I experience your work. It feels like anything can get stuck to it, and sometimes it looks like it happened, and then sometimes it seems to come out of your perversity, and it just happens to be surrounded by this magnificent painting. I mean, the thing that’s so great about your work is that it sort of happens without making itself feel like the point. It seems like it’s just part of your ardor.

BEERMAN: Oh, thank you.

MYLES: So the poem came out of that place.

BEERMAN: Maybe we should read it.

MYLES: Oh, that’s a thought. Let’s keep talking for another minute, because I have one more minute for my tea to be ready.

BEERMAN: I remember you told me, maybe two years ago, that you switched to green tea.

MYLES: Yeah, from coffee. And it’s like, I’m different, man.

BEERMAN: Also, speaking of you and beverages, RIP Diet Coke.

MYLES: Mostly RIP Diet Coke, except if it’s an emergency of some sort that requires consciousness and I have none, like driving cross-country. Dentists say, “Oh, don’t drink any Diet Coke if you’re having oral surgery.” And I was like, “What does that mean?” It doesn’t mean the Diet Coke is great for you the rest of the time, it just means, in this very vulnerable time, Diet Coke will get in there and fuck with you. And I just feel like it’s such an evil substance. One, like cigarettes, that I have an attachment to.

BEERMAN: An evil substance. But for so long, whenever I would see you, I would just bring a Diet Coke. And often, you’d already have one with you.

MYLES:

Hannah’s purse

is sorta

cowhide

purple no it’s

a painting

had to expand

to see naked

Hannah

crouching

paintings like

notetaking

this or that.

I’ve had yogurt

twice today

Hannah used string

it’s one struggle

it’s war

& string & prints

are a thing

you can do. We go on living.

it’s a green stained show

it’s reckless

thank god. I kill plants.

the wellness of dark wall

paper

papier

like a bomb coming

down on a hospital

or some kids

a great abstract painting

can contain shorts. The best ones

you buy this week @GQ

not these I want these &

want to roll in these

safe & reckless paintings

bright green with a rudder

BOOM. These are delightful

and these are macarbre. It works & holds

the worst in times of war

an orange order for a

tote in that old place. I met you

there. Guts & notes

and somebody’s name. A child

says I recognized her

by her coat. The brush strokes

are furious. When I relax

I’m going to watch a cartoon

about war. A sticker. Two parts

of an egg eating itself

She says remember me, my home

my paintings, my world

remember the spattle of turquoise

converging loops, daubs,

In Belgium I think it was

Belgium they posed dead

wrapped in white daubed in blood

an homage to the Palestinians

this is like traffic everything

going left. Coulda been

a daub in this black painting

Hannah undressing

in the rotary. Like language

dancing green. Big valentine

For… Save me from too much

crowd sourcing when I speak

this is lived. This is the dog bed

tiny & wind. A bear climbs

a wall of color

desperately

I can’t measure

this. A scrawl of cord

a message around

a body, a painted animal body

always already dead

more alive than anybody

I will hold you in my sun

thanks for the art

right. Crescendo

of green black

you & I we can just say it

bug eyes boots

above blue brushes

probably not you

divided self

divided selves Which is better?

I’m at the end

your imbalance so symmetrical

always welcoming

she lives

there’s more

more dark skies

more dark messages

more dark furniture

a heart a bed

& some clothes &

Lorca, no it’s

Loba,

the legendary

she wolf & one chamber’s open

and I see

you grazing, ranting

all over

the house

BEERMAN: I love it.

MYLES: I think you are a very poetic painter. The last painting I looked at, there was a bed and there was the painting, and there was Diane di Prima’s book Loba lying there. Tell me, why are you reading Diane di Prima? How did that happen?

BEERMAN: I started reading ’cause I read Diary of a Beatnik.

MYLES: Which is so great.

BEERMAN: I read it twice, so that led me there.

MYLES: Yeah, yeah. I mean, that’s absolutely part of why I love you and your work, cause you’re a beatnik. I’m a beatnik, too. There’s just a selection of us running through the world. And not everybody is a beatnik.

BEERMAN: And there’s less and less of them all the time.

MYLES: I mean, it’s aspirational for some people, but I think it’s a matter of dwelling where things land and figuring out how to do things from there.

BEERMAN: Yeah, I think messiness is very underrated.

MYLES: Yeah. And it’s highly gendered. Tell me about your messiness, please.

BEERMAN: Well, living in what seems like chaos is the way that I’m able to get anything done. While I’m looking for things in the studio, I’m able to have really un-self conscious thoughts and solve problems. While I think I’m looking to find a brush or a pair of scissors or a bottle of yellow paint and I can’t find it, and I’m crawling through here, I’ll have found an accidental sculpture. Then I’ll put that on the wall and deal with it from there. So many things that happen are just consequences of living.

MYLES: Exactly.

BEERMAN: Like, the aftermath of existing, and trying to live, the marks left behind from that… how funny and how ugly and how beautiful they can be.

MYLES: And all at once.

BEERMAN: And how unpleasant and pleasant, sharp and soft.

MYLES: I love being in a space that’s crowded full of things that we love. I just feel like I look up and I see so many books. And it’s like, the labor of my life is removing books and welcoming books and picking up books and finding books. I mean, I like reading more than anything.

BEERMAN: When I come to your home, there are always different books facing forward.

MYLES: Right, right, right.

BEERMAN: Yeah, I need to be surrounded. I need to be in my cave. I have relationships with people, and those are my primary relationships, but also my primary relationships are my paintings. Maybe you feel this way about books?

MYLES: Oh, yeah.

BEERMAN: I can’t sleep unless I have my books and my paintings with me. Even if I’m mad at my paintings, and I have to flip them around so they’re backwards, I still need them to be in the room so I can sleep.

MYLES: That’s so great. It’s almost like they’re humming.

BEERMAN: Yeah, yeah. It’s like, “This conversation isn’t over, and I’m not ready to separate from you yet, because I don’t want to cheat on you. I don’t want to leave you out somewhere else if we’re still having this intense conversation together.”

MYLES: What’s it like to have people around them?

BEERMAN: I feel like I’ve already done my job. When I see other people interact with the paintings, sometimes I feel very insecure and I have a lot of doubts.

MYLES: That seems unbelievable, cause it seems like your work lacks doubt, but keep going.

BEERMAN: Well, sometimes the paintings have a lot of doubt in themselves. I see them as people, kind of, in the way I talk to the paintings, and doubt definitely plays a role in them. Sometimes, they’re not ready to meet anyone. They’re just in their underwear, but they’re not confident in their underwear. They don’t have their clothes on yet, they haven’t figured out if they want to wear a bra, if they don’t want to wear a bra. They haven’t figured out how they want to present.

MYLES: So if a friend is coming over, do you hide them?

BEERMAN: Yeah. I’ll be like, “Don’t look. Don’t look. Don’t look.” And I’ll just trust that they won’t.

MYLES: Understandable. I feel the same way about poems. I mean, this one was unusual, cause I wrote it last night and I didn’t know what it was, but I knew that it was for you. But often, I really need to go through a little period where I know the poem is okay and it’s safe. I rarely read poems that I’m not sure of.

BEERMAN: At one of your readings a few months ago, I really loved how, as a segue in between poems, you were talking about how once you had opened your refrigerator and you were thinking about the idea of writing a poem in the time that it took to open the refrigerator, look inside, and close it. And I’ve been thinking about that with painting, too; the idea of time, and immediacy, and urgency. What can come out in the span of a refrigerator moment is really the span of your whole life.

MYLES: That’s really great.

BEERMAN: I love that refrigerator thing. I think about it a lot. It’s kind of like having a messy studio to me, because it puts certain limitations on stuff. And within those limitations, you have to act more desperately.

MYLES: Yeah, that’s right. I feel that way mostly about writing a dream.

BEERMAN: Oh, yeah?

MYLES: Sometimes I just wake up and I’ve just had a dream and I know that it can completely be a poem. Because the thing is, I’m really forgetting the dream as I’m reporting it. It’s a squirrelly thing that doesn’t really want to be captured.

BEERMAN: Yes, you have to close that refrigerator.

MYLES: Have you ever destroyed a painting?

BEERMAN: Oh, of course. I’m constantly destroying. I’m destroying, and then repairing, and then destroying, and then repairing. I didn’t keep any of my paintings until a couple of years ago. I always lived in a tight, small environment and I didn’t have money for storage, so I never held onto my paintings. I talked about this with Sarah [Wellington] the other day.

MYLES: Keep going, please tell me.

BEERMAN: Sarah Wellington, this amazing artist that we both really love, was in this position where she had to get rid of these paintings and artworks, and she almost was going to have to pay to put them in the trash cause she couldn’t get them removed. She ended up burying them in the backyard of her sister.

MYLES: But burying them in a protective way, where they could be—

BEERMAN: I think so.

MYLES: That’s amazing. I did see something about her burying them and I thought, “That’s amazing.” But I so wanted to rescue those paintings. I wanted to say, “I’ll take five.” And I didn’t say that. Sarah and I, we were activist friends. We were brought together trying to save East River Park and I knew she had this other painter’s life, but I didn’t know anything about it. And then when I was on book tour for Pathetic, Sarah was in Arcata, California, so I thought, “I have to make that stop, there’s going to be a bookstore there.” We saw the redwoods and it was amazing. But I went to her studio, and my god, these are such good paintings.

BEERMAN: Oh, totally. Brilliant. The last time I saw her, she came over to my studio and we made a painting for you that I haven’t given you yet.

MYLES: Oh, I want it. Can you tell me about the show? How long have you been painting these paintings? What’s the deal?

BEERMAN: Oh, well, some of the paintings, for years, and some of the paintings evolve in a day. I’ve lived in a few different places the last little while, so I’ve had all the paintings follow me at each place. And then some paintings develop in a morning or something. I used to think that time had a different kind of value, that the more time you spent in the studio or put into something, the greater it was, or the greater right it had to exist.

MYLES: Right, right.

BEERMAN: Can you relate to that?

MYLES: I can. It’s part of the riddle of being a poet and being a writer, too, knowing that often the work is really fast, and if somebody were looking at that from the outside, they would think, “I mean, you did that so fast, that can’t be good.”

BEERMAN: Yeah. These are real judgements I’m letting myself let go of and accept.

MYLES: Obviously, I write all these different kinds of things, but thinking particularly about writing about art, if I’m asked to write about somebody, I often think, “Oh, I can just do that really fast.” And often I can. And then certain ones, I don’t know why it happens, I’m just like, “I can’t get this.” And it takes a fucking month. And because I get paid money to do these things, it’s enraging. But it’s just this strange puzzle, which is that certain work just wants you longer and you don’t have the keys yet.

BEERMAN: It has you in a death rattle. It wants so much more from me and I’m like, “I don’t even know what you’re asking for and I don’t know if I have it to give you.” Other things, I just sneeze. Once a year, I’ll blow my nose, essentially, and this painting will come out.

MYLES: That’s really great. I want to say appliqué, but how did the nature of you sticking things to your paintings happen?

BEERMAN: That started because, a while ago, I dropped out of Bard for a second and made my family reenact these scenes from that poet’s theater anthology I was telling you about, that Kevin Killian one that you should be in.

MYLES: Right, right.

BEERMAN: That ethos of just taking what’s around you and making costumes, it came from there. And then we started impersonating classic paintings, like Manet, and when I went back to the studio to paint more, I realized I didn’t have to wait for them to dry. I could just stick things on. Also, I didn’t have any money and I had been trying to paint with oil paint up until that time and I just couldn’t keep up with it. In the trash, there was a bunch of free plastic tablecloths, so I started using them as costumes for me to dress up in and then I just started putting the costumes directly onto the paintings.

MYLES: How interesting. What kind of family do you have, when you drop out of college and make your family do poets’ theater around the house?

BEERMAN: Well, they are very special people. At the time, they had this big dilapidated house in Nyack, New York, where Joseph Cornell was actually born.

MYLES: Wow.

BEERMAN: And they didn’t even know that! They got the house in the ’60s, but they found out that he was born there in the ’80s. They’re artists. My mom’s a psychoanalyst, my grandma’s an artist, my brother’s a musician, but they were down for me to make these films of us reenacting Rousseau paintings and reading Frank O’Hara, things like that.

MYLES: Not every family wants to play like that.

BEERMAN: My family’s kind of extreme. They also took in a lot of strays growing up, tons of adopted animals. We had birds flying around the house without cages.

MYLES: So you grew up in chaos?

BEERMAN: Yes, yes. Good observation. A lot of art-making is trying to take a break from the hyperverbal world of my inner life sometimes, too.

MYLES: That’s interesting. What does that mean? I love the sound of that.

BEERMAN: Sometimes I can get so caught up in language, and painting can provide such an antidote to that.

MYLES: Oh, lucky you.

BEERMAN: I’m grateful that I’m able to switch between the two worlds. It’s a real luxury.

MYLES: Do you write?

BEERMAN: Well, sometimes, but I’m much more of a reader.

MYLES: I feel the same. I mean, I draw. I go through periods—

BEERMAN: I love your drawings.

MYLES: It’s such a relief to not be saying words. I mean, I think my writing comes out of the drawing, even though I don’t do that much drawing. I think that’s why I love artists and feel so comfortable with them. And for you, it’s sort of like your home was just a living monument to an artist’s life. That’s just so familiar to me, because that’s the inside of my head, even if books are what I produce.

BEERMAN: I’m so glad you produce the books you produce.

MYLES: Well, thank you.