Five Warhol Sitters On Their Legendary Silkscreen Portraits

In honor of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s blockbuster exhibition “Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again,” we traversed the United States to track down some of the legendary silkscreens—and their equally legendary subjects—to hear the stories behind the portraits that defined a generation.

———

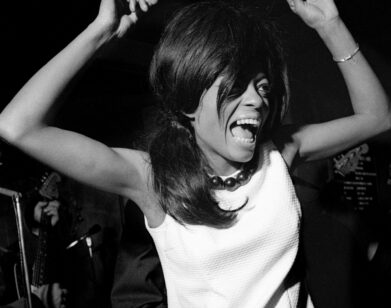

The actress Pia Zadora at home in Las Vegas

“Andy was a fan of mine—believe it or not, I did have one! He was at my debut at Carnegie Hall in 1986, and he pretty much came to see me perform whenever he could. Andy was kind of kitschy and knew that I was, too, so we locked into that. We’d go to the Russian Tea Room and hang out. We were polar opposites: He’d never say a word and I’d never stop talking. One day he said to me, ‘Let’s do you!’ I said, ‘Andy, at this point in our lives?’ So the guy who did the Campbell’s soup cans now wants to do me. But that’s how it happened. I said, ‘Okay, when and where?’ And on that day the limo dropped me off at his studio in Union Square. He told me not to bother with makeup and I thought that meant he’d have his own makeup artist. When I got there he handed me a gingham smock, like the kind you put on when you get a facial. He said, ‘Throw this on,’ and I said, ‘I want to throw this at you. It’s not Bob Mackie, go fuck yourself!’ I remember thinking, ‘Oh, no—what next? This is going to be a huge debacle.’ Then Andy handed me a tube of red lipstick. I said, ‘Andy, I don’t wear red lipstick!’ I was in my twenties and thought red lipstick was for older women. He said, ‘Just put it on.’ I did because I trusted him—it’s Andy Warhol, if he wants me to wear red lipstick, I will. Then he came out with his huge Polaroid camera and said, ‘Stand over there.’ He took a Polaroid, looked at it, and asked to do another angle. So I did another angle and then he said, ‘Okay, thanks, see you later.’ And that was it. I went on the road and when I got back to New York he called me to ask what colors I liked. He’d made one in lime green and another in red. He knew green was my favorite color, but he liked the red. I said, ‘You’re the artist, give me the red. Maybe I’ll grow to like it. Stranger things have happened.’ Now I love it so much I can’t live without it. I perform a show called ‘Pia’s Place’ at a nightclub on weekends in Vegas. Right over the piano is a copy of my Warhol, and sometimes I sing looking into my Warhol face. I’ve had the original hanging in every apartment I’ve lived in since. It’s always the centerpiece of the house, which makes me a narcissist, but so what? It’s a Warhol!”

———

The restaurateur Michael “M” Chow at Mr. Chow in Los Angeles

“It’s important to note that after World War II and abstract expressionism, portraiture had really died out. So it wasn’t very popular at the time. However, since the 1950s, I’d been collecting portraits of myself. A number of artists had done them of me, including David Hockney, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring—even Dan Flavin. In a way, Andy revived portrait painting and I revived portrait painting. Andy did me rather late. I remember it was like ordering a club sandwich: extra bacon, hold the mayonnaise. I said to Andy, ‘Hold the color, lots of diamond dust.’ That was my special order. He did two of me, and they’re very raw. Of all the portraits he’s done, mine look the most like photographs. One was black and white, and one is like a photographic negative with the diamond dust. Just today someone sent a double portrait of me done in red, so there were others. Andy would always do that. He’d make one for you, keep one for himself, and do another for somebody else. He was so smart he didn’t know what day it was! I remember I went to his studio to get my picture taken, and there was a woman at The Factory, Brigid Berlin, who collected penis drawings. She had me draw a penis for her, and I did a very elegant one during my sitting. And Andy is a genius—he takes his huge Polaroid and snaps a lot of pictures. He was so good at taking those pictures and the one of me is simple and powerful. Some of my Polaroids are floating around on the market. Andy kept everything—Mr. Chow chopsticks, a spoon that he stole from the restaurant, everything. He was a true collector.”

———

The educator Corice Arman at home in New York City

“I was very lucky in that my husband [the late artist Arman] really liked to have me ‘hanging around,’ which meant that a lot of artists did my portrait. In 1977, Andy invited me over to The Factory on Broadway to have my photo taken. After he tried a few shots he asked me to take off my top. At first I was reluctant, and you can see that in the image. I’m crouching a bit. I’m certainly not pushing my chest out like a proud cock. [Laughs] But he made me feel confident. In the end, I was one of the first portraits he captured below the shoulder. Andy was a friend and he was always coming around the house. I gave birthday parties for Arman every year. Andy attended the one I threw in 1986. I remember he was standing there, very observant as he always was, and he beckoned me over to him. I said, ‘What is it, Andy? What’s going on?’ And he said, ‘Oh, Corice, you need an update.’ The 1977 one of me was hanging on the wall—both of them, in fact, one over the other in the living room. That’s when he did his second portrait of me, and one of Arman. He was supposed to do a portrait of our 3-year-old daughter, Yasmine, as well. It was going to be a Mother’s Day gift to me. Andy came over to our house to discuss that portrait, and as he was leaving, just before the elevator closed, he put his hand out and said, ‘I want Yasmine’s hair just like that for the portrait.’ That was the last time we saw him. We went to Europe and he was going to shoot Yasmine when we came back, but he died before it could happen. None of us thought he’d go like that.”

———

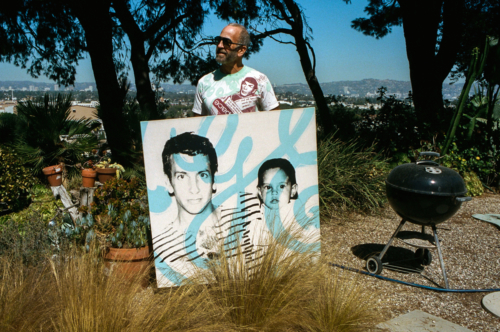

The artist Kenny Scharf at home in Culver City, Los Angeles

“Andy and I used to trade art in the ’80s. I remember going to The Factory in Union Square to have the picture for my portrait taken. I’d been there many times before so I was familiar with how he worked. One thing that was so hysterical and smart that Andy used to do when he worked on the portraits of married couples was diptych paintings. He told me he did that so the couple wouldn’t have to fight over the portrait when they got divorced. He was such a realist! So my wife, Tereza, and my daughter Zena, who was less than a year old, went down there, and not only did Andy do Tereza and I in separate paintings that fit together but he included Zena in both paintings. So if you keep your portrait in the divorce, you also get to keep the kid. One thing I remember distinctly about getting the portrait taken was that Jean-Michel [Basquiat] was there with Andy and he was visibly upset about the attention I was getting. Jean-Michel did not like other people getting attention. It was a little difficult to pose while he was glaring at me behind Andy’s shoulder. The pose was typical Andy: straight on, very blank, without any emotion, and that’s how he made you look amazing. If you’re young, it’s easy, but if you’re older, you were basically just whited out to your bare features—two eyes, two dots for nostrils, and your lips. Everyone looked perfect no matter what age. In my portrait, there’s the imagery of the General Electric symbol, which he went on to use in a number of other silk-screen paintings. But he used that ‘G.E.’ first in my portrait because the G.E. logo was one of that street tags that I used to do. I kept my painting with Zena ever since, and I presume Tereza has hers with Zena somewhere.”

———

The artist Jamie Wyeth at home on Southern Island, Maine

*A 1976 portrait of Jamie Wyeth by Andy Warhol

at Wyeth’s other home in Wilmington, Delaware

“I was introduced to Andy by a mutual friend, Peter Beard, in the mid-1970s. I actually asked Andy if I could do his portrait, and then I basically moved into the Factory at 860 Broadway. We set up a little studio with black partitions for me in the corner next to Fred [Hughes’s] office. I was there for about two years doing Andy’s portrait, along with Arnold Schwarzenegger’s and a few other people’s. Andy’s portrait took two or three months to complete and he posed for me with his little dog, Archie. At the end, Andy said, ‘Now I want to do your portrait,’ and, of course, that only took about five minutes. He’d make you stand in front of the wall and move around a little bit. He took a lot of photos with his Polaroid Big Shot camera. My pose for the one he selected is very romantic, very heroic, with my hand at my chin. It’s sort of the antithesis of the portrait I did of Andy. [laughs] I remember he used to look at my palette when I was painting him and say, ‘You’re using too much pimple paint!’ Afterward, we had an exhibition of the portraits we did of each other at Coe Kerr Gallery on East 82nd Street. I bought one of my Andy portraits and have kept it ever since. He also gave me a drawing he’d done from one of the Polaroids and in exchange he wanted a drawing I’d done of his feet. I’d drawn him on cardboard and it wasn’t big enough for his whole body so I added a piece for his feet. That’s what he wanted to keep, his feet.”