In the Streets

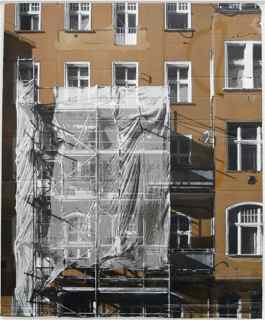

Graffiti artists producing illegal out-door art often breathlessly bang on about bringing “the street” into official art institutions. But “the streets” they mean to evoke are quite different from the calm, understated and ordinary city blocks which Evol brilliantly renders for his first solo show at the Wilde Galerie. Rather than recreate street scenes busting with human activity and renegade energy or provocatively desolate dystopian cityscapes, the artist who grew up in a German suburb and now lives in Berlin spray paints quiet scenes of bland prefab buildings on cardboard. The ten recent paintings which he produced on discarded packing material, and the one walk-in-sized installation, are all primarily grey, black, white and tan. The tan colour comes from the cardboard itself, which he uses as a base—allowing the scars and marks from where tape was torn to feature as weathering on the tired buildings he represents.

While Evol also incorporates graffiti into his city scenes, the graffiti isn’t a creative counter-point to the paintings’ dreary mood, like it is in Nigel Cooke’s oil paintings. Instead, it enables him to integrate the writing that already marks his recycled cardboard canvases into his imagery, just as the marker writing made for the boxes’ original use is incorporated into the street scenes as unimaginative tags. The Hopper-esque scenes’ subtle play of light and dark suggest they are taking place in mid-day when people are awake. Yet beside the tags on the wall, bicycles, cars, recycling bins and occasional shadows spotted behind window-frames, his streets are unpopulated. Nevertheless, they don’t appear ominous or hopeless. Rather, the beauty of Evol’s art is that he clearly feels genuine empathy for the occupants of these uninspiring yet comfortable habitations.

ANA FINEL HONIGMAN: How would you describe the urban settings you paint?

EVOL: Basically they are ordinary houses, where ordinary people live, like you and me.

They didn’t dress up to impress you, they just reflect the stories that happen there. I am more interested in the stories next door than in artificial sensations.

Evol, Balconia, 2009

AFH: What are your emotional associations with the environments that you depict?

EVOL: I think of these as something like a portrait of the area of Berlin I moved to almost 9 years ago. Most of the buildings looked like the ones I paint back then. Most of them weren’t renovated. You wouldn’t have called a posh neighborhood. In fact, it appeared rather poor. But it was rich for space and possibilities for people to make things happen. People could do anything because no one really cared, and you didn’t need big resources to do something spontaneous or temporary. Area others could call “rundown” or dilapidated, were in fact pretty charming. There was visible history on the facades with all their marks from generations of inhabitants. The buildings silently told stories of their inhabitants’ existences. That is what interested me. Berlin did not have the isn’t it the same kind of “charm” that an ordinary tourist seeks in rome or small village in the South of France but it was not charmless. Only then all activity and freedom made the area got more and more popular and, just like anywhere else, were gentrification happens here too. Prices go up, thousands of gallons of yellow paint were dumped on those buildings, destroying their unique charm, the people and the possibilities. So, for me these paintings are a symbol of what the neighbourhood once was.

AFH: Do you feel that the work you do in the street is a more authentic version of what you produce for the gallery? Is streetwork more authentic than gallery work?

EVOL: They are two totally different things, even though the same topics interest me. My work on the street is site-specific. When creating art on the street, you are putting your work in a surrounding your “audience” is familiar with, but wouldn’t expect to have function as an art space. The downside is that you’re excluded from the reactions. The only feedback you get is when learning whether a piece was destroyed. And you are very limited in materials that you can use. You are especially limited with time. Time is what I have when working on a piece for a gallery. Then I can use a different language because I am liberated from the limitations on the street, and because I know that my audience is already primed and focused. This enables me to direct attention to different things.

ANA FINEL HONIGMAN: Why did you decide to lessen the overt political messages in your paintings for the Wilde Galerie?

EVOL: I prefer a more subtle way of attracting attention to my messages. I have ads screaming at me all day long already. Plus I don’t see my work as mainly politically motivated. It is a comments on my surroundings and I would rather that people make up their minds own instead of getting delivered pre-packaged short-term advisory lesson from me.

ANA FINEL HONIGMAN: I hear that you’re not happy with the term “street artist.” I can understand why the particular aesthetic associations of “graffiti” are unappealing but how does “street artist” not represent you or your work?

EVOL: I would rather see myself as an artist, who enjoys leaving his marks in the streets but I also enjoy working in a studio preparing marks to be left elsewhere. The meaning of “street art,” to me, implies that it is only on the street. That description simply doesn’t represent all of my work and I feel that term “street art” has been used in a patronizing way. I find it sad that brilliant interventions in public space are stuck in the same drawer as the loveless self-ads that you may find in a lot of those so called “street art”-coffee table-books. The term is so flattening, I guess because otherwise the drawer doesn’t close. Because of these associations, a lot of really innovative people are overlooked. I find the term simply unfair to all those great artists who develop an individual way of reconsidering public space.