Andy Warhol’s Contempt for, and Adoration of, the American Performance

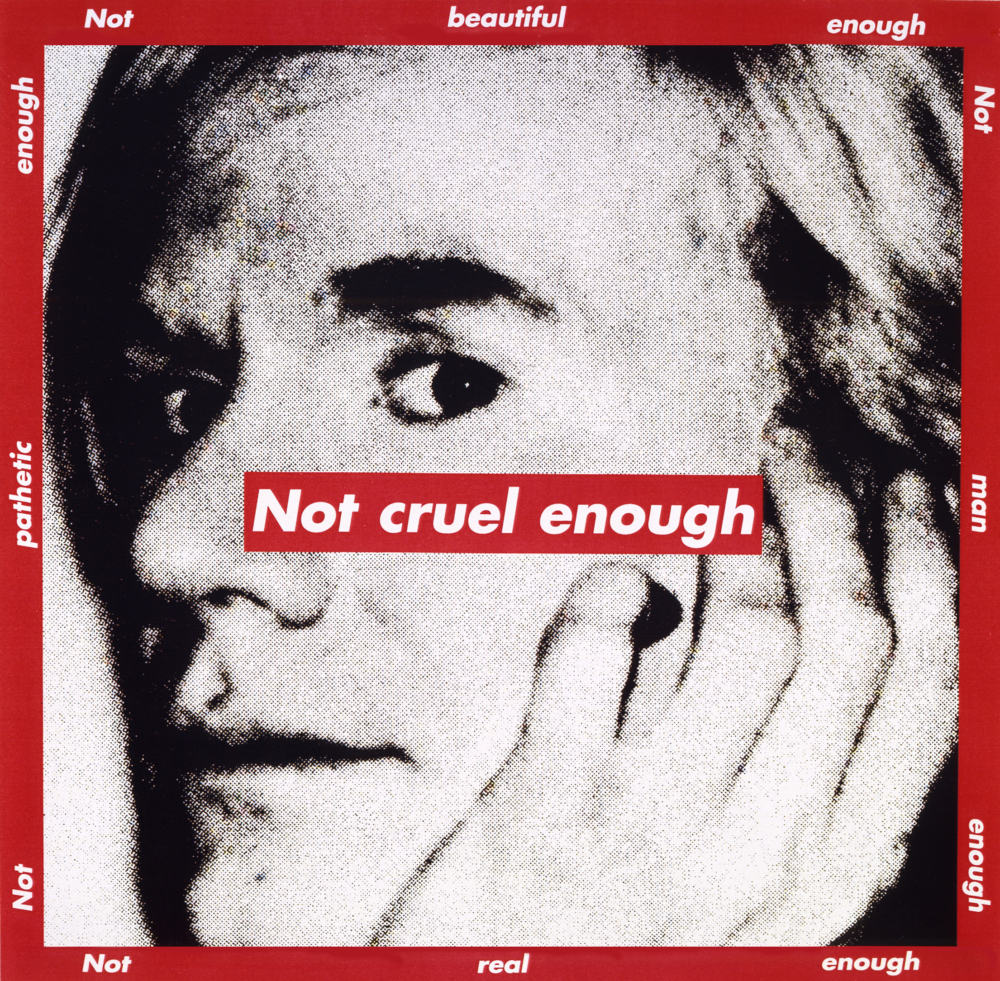

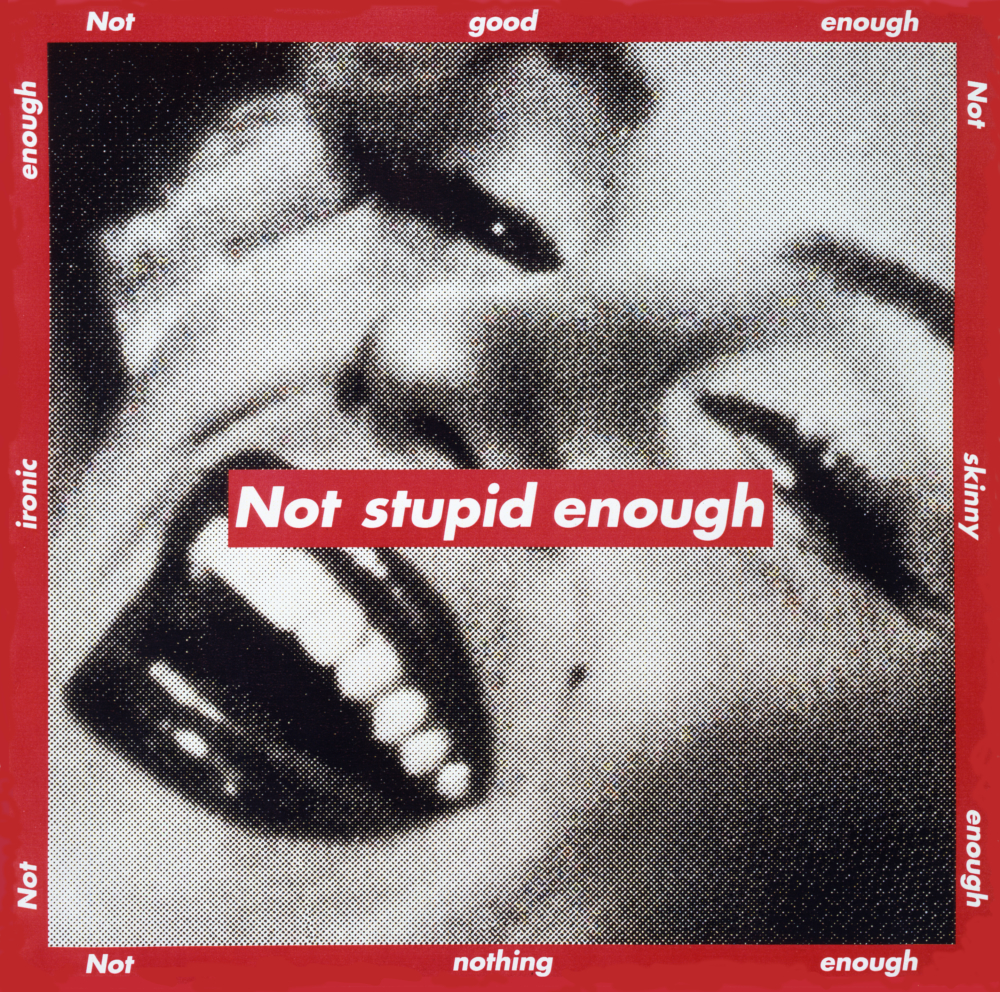

“Untitled (Not cruel enough),” 1997. Artwork by Barbara Kruger. © Barbara Kruger. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery.

The conceptual artist, educator, and writer Barbara Kruger is one of the most fastidious readers of American culture as we know it today. The following essay is excerpted from Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again, recently published by Yale University Press as the catalogue for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Andy Warhol retrospective. Kruger’s 1990 work “Untitled (Questions)” was reinstalled not long ago on the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art’s north facade ahead of the 2018 midterms. It will remain there until the 2020 presidential election.

———

The most beautiful thing in Tokyo is McDonald’s.

The most beautiful thing in Stockholm is McDonald’s.

The most beautiful thing in Florence is McDonald’s.

Peking and Moscow don’t have anything beautiful yet.

—Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, 1975

Aside from serving food relatively quickly, McDonald’s is about a particular kind of presentation: the American rendition. It condenses the look of the last thirty-five years of highway architecture and public eateries into the time it takes to grab a bite. Above all, it is the primary vision of businessmen concerned with profit and efficiency in the field of food services. But McD’s brand of global culinary imperialism and the brass-tackism of its financial acumen was of little concern to Andy Warhol, to whom McDonald’s was both merely, and most importantly, beautiful. He might have also called it adorable: as in showered with fun and crowned in cuteness. His comment can read as a happily relieved relinquishment of the critical, a resolutely numbed-out dose of enthrallment. But maybe it can also work as a dislocator, courting the negative with a kind of languid irony. Andy Warhol always seemed to hanker for that really pretty line that wandered unmerrily between contempt and adoration.

The adoration was the easy part, like the icy vehemence of the kind of guy who would stand outside the Pantages Theater on Oscar night, clutching a bouquet of roses for one star or another. For the guy who wanted to be reincarnated as a diamond on Liz Taylor’s finger, proximity to fame was almost enough: a sort of elixir, an enabling connection plugging him into the glittering dispensations of prominence. His own celebrity became part of a baroque networking, a bright constellation of havers and doers who could inhabit the VIP lounge of the universe, where everybody who was anybody would show that they could never be mistaken for a nobody.

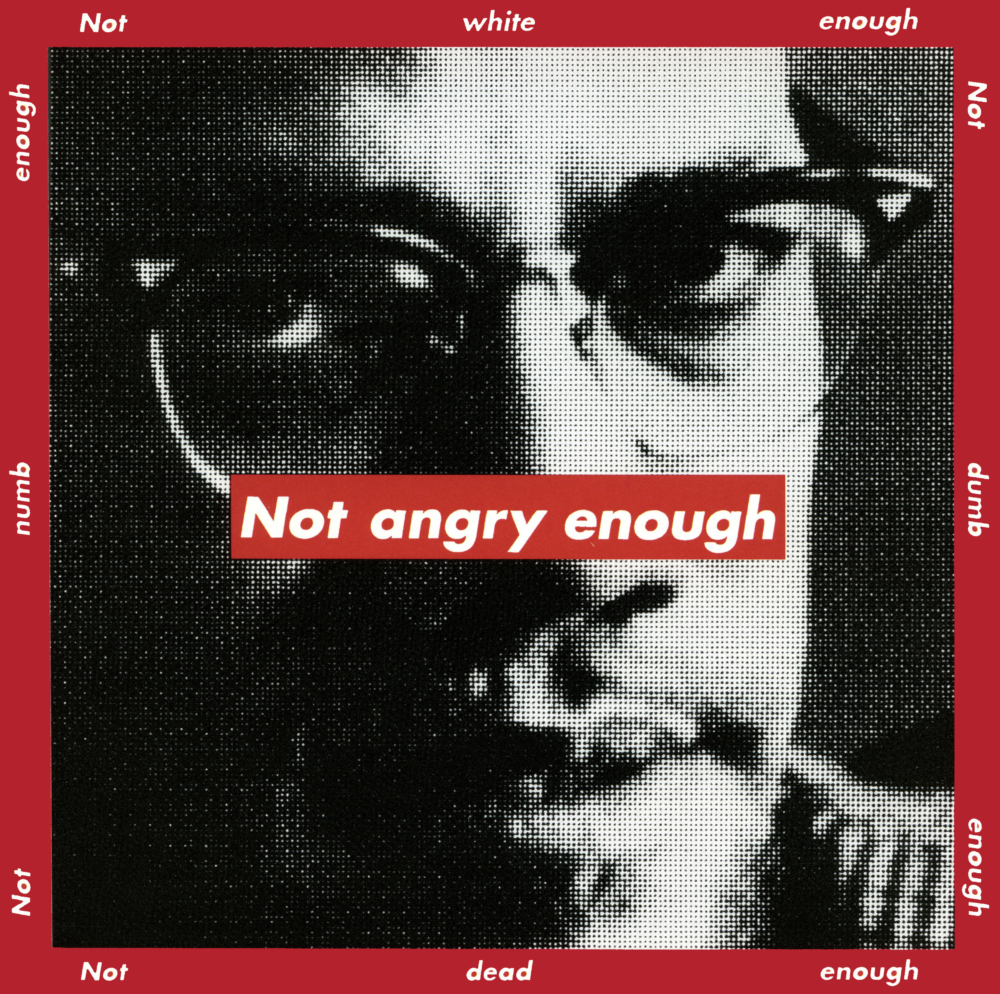

“Untitled (Not angry enough),” 1997. Artwork by Barbara Kruger. © Barbara Kruger. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery.

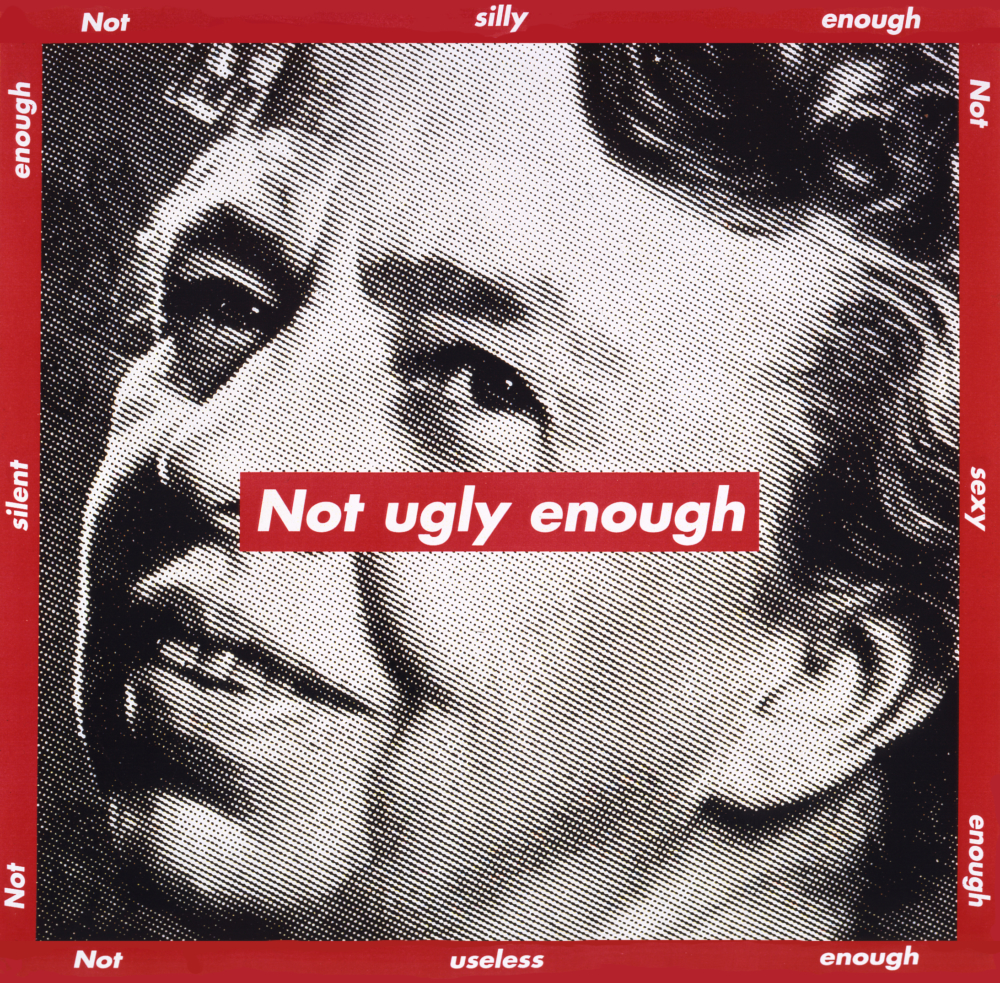

“Untitled (Not ugly enough),” 1997. Artwork by Barbara Kruger. © Barbara Kruger. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery.

All these yens for glamour and fame, coupled with a smooth ability to cut through the grease of wordy, “unpleasant” complexities and historically grounded explanations, made for the stuff of Warhol’s work. The fashion illustration, the early “easel” work, the repertoire of silkscreen virtuosities, the paintings, the movies, Interview, the photographic activity, the books, and the resonant figure of Andy himself were informed by a coldly smart reading of American culture. He cannily appropriated a seriality of signs, jokes, and icons that seemed right on the nose. But that’s not surprising, since Warhol was so taken with the face of things.

It was this face, this parade of glaringly alluring visages, that soaked through Warhol’s production, that floated to the surface of his work and showed us how images of certain well-known and sometimes smiling heads could make idleness seem so awfully busy. Inhabiting a kind of gauzy villa of narcotized smirks, they might even suggest, beyond the irony, a passion. The passion for the elegant figure. The grace of a stunning body working a gorgeous garment. Indigo-shadowed eyes glancing at a boy who’s always looking the other way. We are breathing inaccessibility. Our desire is merely to desire. We must see and be seen and the next party is always the best.

Mixing scattered serialities with the promiscuous capabilities of the silkscreen process, Warhol crammed his images with the commodities and commotions of his time, and made them belt out a national anthem which sounded suspiciously like “Money Changes Everything.” The singularity of specific icons was processed through an assembly line of fluent, varietal repetitions. But although these procedures were employed with machine-like detachment, the work, nevertheless, has the feel of a cottage industry in which the tiny mismatches and eccentric registers of the silkscreen process become as resonant as de Kooning’s rapturously brushy orchestrations. From the ironic presentation of the renovation of affliction (the nose job, dance instruction, and paint-by-numbers pictures) to his portraiture, Warhol’s images coalesced into a facetious cataloguing of photographic and painterly gesture: a testament to inaccessibility, to the rumor of a stainless beauty, to the constancy of glamorous expenditure.

“Untitled (Not stupid enough),” 1997. Artwork by Barbara Kruger. © Barbara Kruger. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery.

The tony veneer of these incisive parodies and icy vanities could serve as screens on which to project Warhol’s raw and powerfully tedious movies. Kiss, Blowjob, 13 Most Beautiful Women, Poor Little Rich Girl, Screentest, Face, Chelsea Girls, and even Empire (with its attention to the “face” of an anthemic structure), all seem to be searching for the perfect visage. The “up close and personal” talking head, coupled with the enlargement of the film format, produced the ironically doubled myth of “Super Star”: a site at which the marginalized could enthusiastically produce the image of their own (im)perfection: in which the generic position of “star” was doubled over and, rather than choking on its own artifice, swallowed it whole and proceeded to describe the experience to us for what seemed like an eternity. By suggesting that people could spend their lives lying in bed, talking on the phone, and cutting their bangs, these films foregrounded both the fun and charm of being wasted, and the hard work it takes to live another day. They create different readings than the gelled signifiers of the static portraiture, and proceed to tell a story about the thin line between glamour and shit. They satirize, yet embody, the star system, the impossibility of everything, and the sublimity of the mundane gesture. They are contemptuous of the spectator as masochist and invite an intelligently hasty exit. They are clean-cut examples of film as idea, combining the “creative” dispensations of so-called avant-garde filmmaking with the look of Sam Fuller’s perpetual complaint that someone is staring at him.

Throughout all this work, Warhol functioned as a kind of engineer of retention: a withholder who became the doorkeeper at the floodgates of someone else’s expurgatory inclinations. His acuity can be construed as a kind of coolness: an ability to collapse the complexities and nuances of language and experience into the chilled silences of the frozen gesture. He elevated the reductivism of myth and mute iconography to new heights of incommunicado. Mixing the posing of stunned subjectivity with the confessional forays of raging objectification, he produced something that sometimes looked like a talent show in the asylum. Like any good voyeur, he had a knack for defining sex as nostalgia for sex, and he understood the cool hum of power that resides not in hot expulsions of verbiage but in the elegantly mute thrall of sign language.

Originally published as “Adoration,” Village Voice 32, no. 18 (May 5, 1987), Voice Art Supplement, pp. 10–11