National Sawdust Opens in Brooklyn

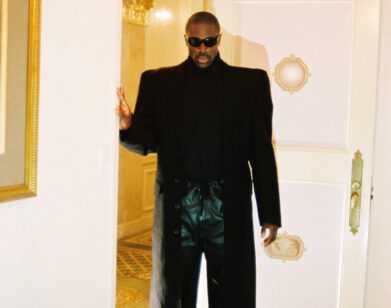

PAOLA PRESTINI IN NEW YORK, SEPTEMBER 2015. PHOTO: HELENA CHRISTENSEN. HAIR: BLAKE ERIK. DRESS: NICOLAS K.

National Sawdust, a sprawling 13,000-square-foot space for musical and artistic exploration and performance opens tonight in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The inaugural performance will include three world premieres, featuring the talents of composer Nico Muhly, cellist Jeffrey Zeigler, and musician Bryce Dessner (of The National), as well as two pieces composed by one of the world’s top 30 composers under the age of 40: Paola Prestini. Prestini, who also serves as Creative and Executive Director of the non-profit organization, has worked with Kevin Dolan (who is also her partner) for the past five years to develop the space and its programming alongside an advisory board that includes Dessner, Muhly, Philip Glass, Laurie Anderson, Suzanne Vega, and many others. National Sawdust will host artist-in-residencies, groups-in-residencies, staged performances (with every type of music, from jazz to classical to experimental and modern indie), and talks by some of the leading minds in music.

“What’s hard in music is that you can’t hang a piece of music on the wall,” Prestini says while speaking with close friend and advisory board member Helena Christensen. “When someone commissions me, they’re not going to own that piece. It’s very ephemeral.”

This sense of ephemerality is exuded through the residencies: while each artist may have a limited time at the space, the hope is that each person or group leaves with a lasting and deeper understanding of their art form and how to bring that into the professional realm. Before opening night, Prestini met Christensen in New York. After taking the above photo, the two women sat down at Christensen’s home to discuss National Sawdust, their backgrounds, and more.

HELENA CHRISTENSEN: I would like to know, first of all, your heritage, I know it’s Mexican and Italian, but you live in New York and are very much a New Yorker. So on which side are you Italian, and Mexican, and how much time did you spend there growing up?

PAOLA PRESTINI: I was actually born in Italy to two Italian parents, then came to the States when I was very young. We moved to Nogales, a small town on the border of Arizona and Mexico. Culturally, I really loved Mexico and grew up speaking Spanish and singing Mexican folk songs, but Italian is my background. Growing up on the border is a really incredible existence because you have your foot in two worlds. We lived on the American side and definitely crossed over all of the time.

CHRISTENSEN: So you could be standing with a foot in each side?

PRESTINI: Exactly. It’s incredible because you think about the Italian, the Mexican, and the American upbringing—how those things come together for me has created this very exciting bed of cultures to draw on and this respect for different cultures, which I think is profoundly embedded in me and the way I function.

CHRISTENSEN: And it must have influenced your musical background.

PRESTINI: Very much so.

CHRISTENSEN: When did you start to think that music was something you were really passionate about?

PRESTINI: I was playing a piano right away [at age three or four] and apparently I took to it very quickly, [but] definitely not a prodigy in piano. After a while I realized that I didn’t like practicing and what I really liked was writing music. That started happening at 9 years old.

CHRISTENSEN: Because then you could be at your own speed and you could be the boss of it.

PRESTINI: Which is very me.

CHRISTENSEN: I have noticed that, yes.

PRESTINI: [laughs] One of the things I still love so much are Mexican songs, folk songs, the folk culture—and vocal music. In our house we had singing all the time. It was everything from folk music in Mexico to operas. I think once music is in your life, it informs the way you listen to things, it informs everything.

CHRISTENSEN: I think it’s one of the most important gifts you can give a child, to let them grow up in a musical environment. I would play classical music to Mingus [my son] when he was in my belly.

PRESTINI: We did the same with our son. Helga [Davis, the vocalist and performer] would actually sing to my belly when I was pregnant. He recognized her voice; it was incredible. One of the things I found so inspiring was when we were starting out with this dream, you threw yourself into it, and we had so little. We had this dream to start National Sawdust.

CHRISTENSEN: Tell me about the beginning of National Sawdust.

PRESTINI: The beginning started with Kevin [Dolan] and his vision to help young, emerging artists. Music helped him find himself in such a profound way. He turned around immediately and said, “If music can do this to me, and I’ve seen the power that music has in so many people’s lives, what can I do to give back?” So this was seven years ago, and five years ago I came into the picture. My dream, aside from composing music and doing multimedia and opera, had always been to start a school.

In my head it was this idea of doing a circular education, how one discipline would inform another. After going to Julliard and realizing how complicated it would be to be a female composer, I realized that it wasn’t enough to worry about my career; I had to think about the context within which I was creating and what I could do to help that context. So when I met Kevin, it was this wonderful, synergistic meeting because it wasn’t a school; it was a place where we could really help and nurture emerging artists into professional life.

CHRISTENSEN: It’s quite amazing how something like that happens at the right moment in your life. It’s a strange thing, where you heart and your mind reach a mutual acceptance of something. It’s almost impossible to force it; it has to happen organically.

PRESTINI: Being a practicing artist, I feel like I know what artists need. That’s really important. What we didn’t have growing up—in my 20s, in New York, it was so hard. There was so little support when people don’t know who you are. I don’t think you want to take that struggle away, but this [project] is saying: What are the things we can do to keep artists in New York? What are the things we can do to support them financially?

CHRISTENSEN: Art has a tendency to come from some kind of struggling.

PRESTINI: Financial. Think about Phillip Glass and Robert Wilson, they had no money when they created Einstein.

CHRISTENSEN: There are so many cases of that, but I’ve always thought, “Does art have to come from struggle?” In this case, National Sawdust is enabling them to live their dream and create under simpler circumstances, where they have space to let everything flow. Maybe you should explain what National Sawdust stands for.

PRESTINI: National Sawdust is a venue devoted to the discovery of music across styles. It’s entirely artist-led, with curators, artists-in-residence, groups-in-residence. My idea behind it is that the great artists we have in residence aren’t just incredible creators, but also curious listeners. So there’s a sense of always paying it forward and always thinking of yourself in a larger context.

It’s also a recording studio designed by Arup, this incredible acoustic firm. The whole space is called a “box-in-box construction,” so it’s built on springs, which means that sound can’t travel through the air or through the ground. It meets the same P and C value as the world’s finest recording studios.

We talked, at the beginning, about both of us living in these different cultures. For me, the thing that attracted me to New York and kept me in New York was this feeling of always being amongst people from incredibly different backgrounds. Even me sitting in front of you—New York can bring the impossible to you if you search hard enough and dream hard enough.

CHRISTENSEN: Exactly. Circumstances and destinies bring us all together. It’s a little effort from a lot of people, which can make a huge difference. This project has been personally beneficial to work on. You feel good to work on something like this.

PRESTINI: I think also, there’s something in you that’s so musical and artistic.

CHRISTENSEN: I don’t know how I would live without music.

PRESTINI: I think people can’t live without music. I also think about the way we listen to music. When I walked into your apartment, there was classical music. When you walk into my home, it’s kind of the same; you go through classical music, my own music, music that’s contemporary, jazz, experimental. That’s the way we listen today, that’s what I want to have in this space, that fluidity of styles. There are so many different styles to choose from today. It’s really about weaving them into a unique voice.

CHRISTENSEN: How do you create a piece of music?

PRESTINI: That’s a good question. You were saying something earlier that I liked, which was this sense of not being able to pinpoint when magic happens in life. There’s something about that in the creative process, which is for me flow. There are moments when I look back at what I’ve written and I honestly can’t remember writing it. It’s as if someone else did it. It’s that moment, which you can achieve in any profession, but it’s that moment where everything in you is working simultaneously. There’s a subconscious mind—obviously a conscious mind as well—and it just comes into what you’ve done.

CHRISTENSEN: I think we’re all ultimately born with music inside. Different incentives bring it out. It could be a childhood, a heritage, a culture, going to amazing schools, having amazing teachers. You went to Julliard. The crazy teachers, that movie, Whiplash—that was so unbelievable. I don’t know if it’s like that. There are probably teachers all over the world who have a bit of a tendency of that.

PRESTINI: There are. When I think back on what I took from Julliard, it was the incredible performers. Because it was placed in New York and there was such an influence on career and next steps, it felt like a wonderful push into professional life. When I was at Julliard, I started the non-profit that I still direct today, VisionIntoArt, and that helped me commission my own work and commission others. So in that sense Julliard wasn’t that kind of environment where you go to college, meet your friends, and have fun. It was like, you go to Julliard, you study.

CHRISTENSEN: [There is] something very beautiful and poetic about that, that you’re so committed at such a young age to something on a completely different level—the structure, the discipline, the effort, and the talent. A lot of people have talent and would not be able to stay under such a disciplined structure. It is such a deeply ingrained passion.

PRESTINI: That’s something I thank my lucky stars for, the way I kind of always knew what I wanted. It didn’t always come out the way I had thought, or as soon as I had wanted, but looking back I wouldn’t change a thing. I feel like now I have the things that are the recipe for a happy life. I have my son, who I love, a loving partner, who I adore, and a life in music.

CHRISTENSEN: And respect. In a relationship, mutual respect is probably the most important thing. You guys do that, you perform, do shows together. There’s so much beauty and love in watching you introduce your partner. It always gives me goose bumps.

PRESTINI: Thank you. I’m very proud of him. The other thing is, to me, when two souls come together, it’s two worlds coming together. You’re not looking in that person for answers or completion, but you’re looking for this communion, and I definitely feel that through the music… You never stop working, though. In a way, it’s like when you love what you do, what you do seeps into everything, and then you never stop.

CHRISTENSEN: But it doesn’t feel like work. It’s just an ongoing conversation, where you both evolve.

PRESTINI: It’s very cute to see Tommaso, our son, witness that. Now he’s playing the cello, he is part of these discussions, and at a very young age is understanding artistic concepts.

CHRISTENSEN: Someone is going to be talking to him when he’s older and saying, “How was your childhood?”

PRESTINI: He’s going to say, “It was terrible, I was on the stage all the time, I hated it.” [laughs]

CHRISTENSEN: Now, Mingus is not looking to become a model. [laughs] Creating a piece of music for you must feel like a baby that you’re letting into the world: You’re letting it flourish, evolve, and grow. The people who listen to it, they grow and evolve with that baby you’re putting into the world. That’s got to be what it feels like.

PRESTINI: It does, and it lives a whole different life once it’s in the hands of performers.

CHRISTENSEN: Can you fall asleep at night when you’re working on a piece? I imagine the music keeps playing in your head.

PRESTINI: There isn’t a moment in my life where I don’t have sound in my head and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

CHRISTENSEN: When I get into a project and I really feel for it passionately, I almost zoom out everything around me and it’s a vortex. That’s the feeling I love. It doesn’t matter what goes on around you, you’re so committed you can hear yourself breathe.

PRESTINI: Totally. If you think about that magical thing when you hear [or see] something and your life is changed, it happens through many different art forms. But what makes music so spectacular is that it’s in the moment, it’s live, it’s a moment of connection.

CHRISTENSEN: And how many people it reaches that you will never meet. It goes right into their bloodstream and touches them.

PRESTINI: That’s the thing that makes me want to work so hard. There is this challenge in music, but at the same time this incredible benefit. I often think about the qualities I look for in musicians; I think musicians today need to be cognizant of the world they live in and they need to be educating people, they need to be generous.

CHRISTENSEN: They have the power to be. It’s a huge responsibility. You can go with your own flow and ideas and that might still affect people, but you can also sit down and think very hard, “What I put out now is going to make a difference.”

PRESTINI: How you balance a career in the arts today is very different. It’s very hard to have a traditional life where you teach and you write your music. There’s a lot more space for interesting careers. You might be an entrepreneur, you might be an activist and at the same time be this incredible creator. People often ask me, “How do you do it?” I get that people want to know because it looks complex, but to me it’s not. I get to listen to so much music because I curate it and I program it, and that encourages me to write and when I write I have my own space.

CHRISTENSEN: It’s like a beautiful circle.

PRESTINI: Exactly, it’s a complete circle. Before we end, I want to say thank you for seeing me through your lens, and for your artistry. I have enjoyed today so much, and thank you for making me feel beautiful.

TONIGHT’S CONCERT IS SOLD OUT, BUT A LIVE STREAM WILL BE AVAILABLE HERE. FOR MORE INFORMATION ON NATIONAL SAWDUST, VISIT THE ORGANIZATION’S WEBSITE.