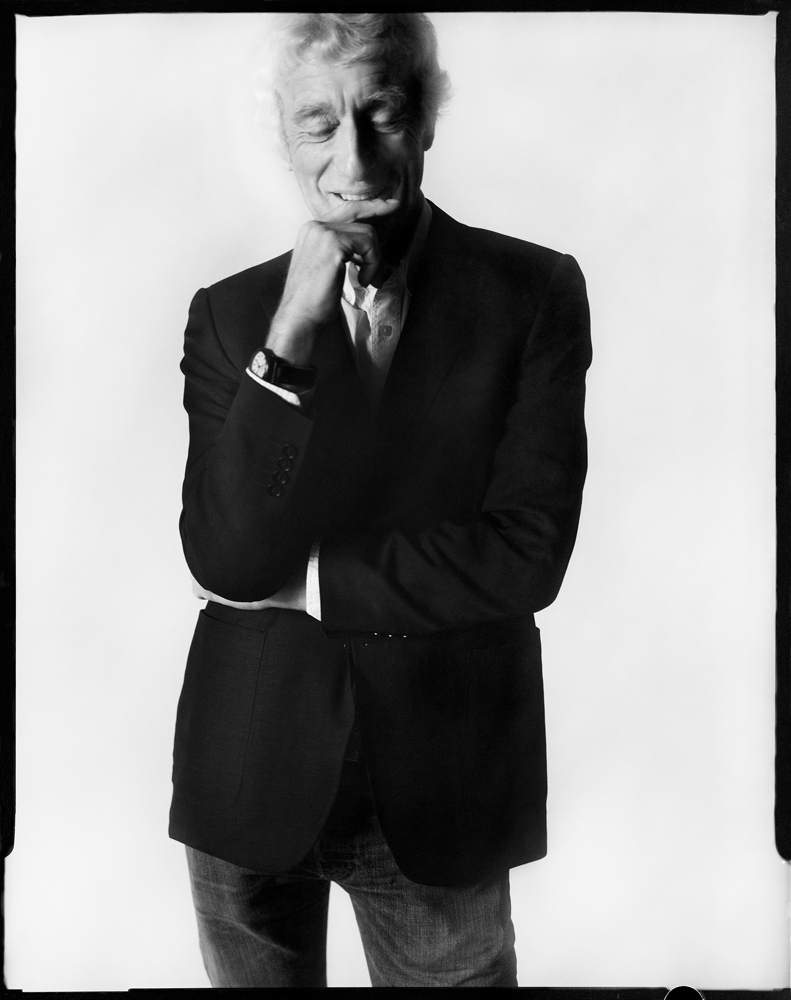

Roger Deakins

I love to watch an actor within a shot . . . I feel I’m the first person watching it. Roger Deakins

There are images in the films of Roger Deakins—including in his newest collaboration with director Denis Villeneuve, Sicario, and going back to his pioneering early work on classics like 1984 (1984) and Sid & Nancy (1986)—as arresting and iconic as anything in the history of film. But his images never get in the way of the story they are helping to tell. In every case, from the desolate parade of busses under a rosy-fingered dawn in the border drama Sicario, in which Emily Blunt and Josh Brolin play government agents trying to break the drug cartels, to the snow-speckled bear-suited dentist in the Coen brothers’ True Grit (2010), from Brad Pitt‘s angsty walk in the grass in The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007) to Tim Robbins’s sewer romp in The Shawshank Redemption (1994), every inch of Deakins’s canvas is in full service of the narrative it is driving. Which may be why he is so beloved by some of the greatest filmmakers around—including the Coens, with whom he has made a dozen movies, Sam Mendes (three titles together and counting), Edward Zwick, and Villeneuve (both of whom have made two a piece with Deakins)—and so oddly underestimated by the Academy (12 nominations, but only nominations, for best cinematography).

As the filmmaker from Torquay, England, now 66, explains to his pal and fellow photography enthusiast Jeff Bridges, this talent for storytelling started for him after college when he was making documentaries for British television.

JEFF BRIDGES: Hey there, Roger!

ROGER DEAKINS: Hey! How are you?

BRIDGES: I’m well. I’m here in Santa Barbara, finished working on a movie not too long ago in New Mexico [Comancheria], written by the same guy who wrote Sicario [Taylor Sheridan]. That guy’s a good writer, huh?

DEAKINS: Yeah, he is.

BRIDGES: This is a new turf for me, being an interviewer, so let’s just jump in with how we first met. God, that’s almost 20 years ago, man. That’s hard for me to reel in.

DEAKINS: Yeah, The Big Lebowski, [1998]? Was it that long ago? Time flies. [laughs] I’ve been working with the brothers for, like, 26 years now.

BRIDGES: Jeez, man! I counted the films. A dozen?

DEAKINS: Yeah, around there.

BRIDGES: So when you started out, what was your first memory of saying, “Wow, this is something I can do for the rest of my life as a profession”?

DEAKINS: Well, I suppose everyone gets into it in a different way. I loved film when I was kid because I was in a film society in Torquay, which is near where I am now, down in Devon. And I used to go and watch films. I fell in love with movies. My dad was a builder, so I didn’t have any connection to the arts at all. I never really considered film as a career, but I knew I didn’t want to be a builder. [laughs] So I went to art college, and it just gradually happened. I heard that the National Film School was opening up, so I applied. And when I first started, I saw myself shooting documentaries or making documentaries, which is what I did, mostly, for a number of years. So it was quite a surprise how I found myself shooting features. It was like my wildest dreams as a kid collided, you know?

BRIDGES: Did you start with still camera?

DEAKINS: Yeah. When I left art college, I was a still photographer for a year. I was working for an art center in North Devon that started a record of rural life in North Devon before it disappeared all together. Because at that point, it was the early ’70s, and the rural way of life was changing quite quickly.

BRIDGES: You directed documentaries as well.

DEAKINS: I directed some. Sometimes I was what they called an assignment cameraman—I’d go off with a sound recordist, so there was no director. So I would shoot, basically, a documentary, and the editor would be named the director. [Bridges laughs] And it was produced for television. At the time, I didn’t mind. I suppose I do mind a bit now. I didn’t mind back then because I was getting the work and the experience. And, as far as I was concerned, I was more or less making the films.

BRIDGES: Did you work your way up? Were you, like, a focus puller and an operator? Or you just jumped right in?

DEAKINS: No, I was shooting documentaries, mostly, and a lot of rock videos, and then I got the chance to shoot a feature film with a guy I knew at film school. He was doing a fairly low-budget feature film for Channel 4 television in England [Another Time Another Place, 1983]. The film was released theatrically, and it was very successful. It actually played at the Cannes Film Festival. I didn’t really turn back after that. I made two other films [1984 and White Mischief, 1988] with the same director [Michael Radford] in rapid succession.

BRIDGES: Wow. That’s a great way to do it.

DEAKINS: Yeah, I was very lucky. I mean, the big break was really getting into National Film School. If that hadn’t happened, I don’t think I would have gone into film at all. I might’ve become a photojournalist or something.

BRIDGES: With our biz, it’s such a collaboration. You’ve got your team you travel with from movie to movie.

DEAKINS: Yeah. I work with Bruce Hamme, the dolly grip. I worked with him for the first time when I first worked with the Coen brothers. And Andy Harris, the assistant camera; he was on Lebowski and True Grit with us. I met him on Shawshank Redemption, so I’ve been working with him for a long time, too.

BRIDGES: That really helps. Are you drawn to certain stories that you like to help tell? Or when you get the material, it either affects you or it doesn’t?

DEAKINS: Well, material, sure. I’m sure it’s the same with you. Obviously, with Joel and Ethan, I pretty much will do anything. But usually there’s certain kinds of material I like. I like historical pieces, but it’s not often that I get that kind of material. So usually it’s my reaction to a script. If I don’t feel it’s gonna make a film that I would want to go see, then I don’t really want to work on it. I think it’s too much of an involvement of time in your life to work on something that you don’t actually have some sort of passion for, especially at my age.

BRIDGES: I know what you mean. I do my best to push them away unless it really hooks me. It’s tough to hook me these days. I find it harder and harder.

DEAKINS: Well, yeah. I don’t think that’s you so much as the material that’s around, isn’t it?

BRIDGES: Well, that’s true. That’s where it starts, the story. It’s like the brothers—I remember when they came to me about True Grit, I said, “Why do you guys want to make that?” And they said, “Well, have you read the book?” I said, “No.” And then I read the book, and I saw that it read like a Coen brothers script.

DEAKINS: Yeah. I had the exact same reaction. “Why you want to do that?”

BRIDGES: In your recent movie, all of the elements come together—the set design, the editing, the photography, the direction … Something I love about your work, and certainly with this film, is it’s just right. How do I describe it? I think this goes for almost all the different facets that are included in the movie—makeup, sound—your stuff just draws the viewer in in such a beautiful way.

DEAKINS: Oh, thank you.

BRIDGES: It’s real. It feels like how the eye sees, having those exteriors kind of blown out. Was Sicario shot on digital?

DEAKINS: Yes.

BRIDGES: Do you like this digitizing of our stuff?

DEAKINS: I think it’s inevitable. It’s funny—I was just working with the Coen brothers over the winter on this film Hail, Caesar! And they wanted to shoot film, so we shot film. I think my choice might have been to shoot digital, but I enjoyed shooting film again. But I think that film has had its day, and I believe there are great advantages to the digital process, actually.

BRIDGES: You don’t have to load it so often!

DEAKINS: Well, that’s it. It must be great for an actor that you don’t have interruptions all the time. I think it’s good in that you have a monitor on the set that’s got it calibrated, and you can show the director exactly what you’re talking about. I don’t really believe in the mystery of cinematography—what happens in the camera is what the cinematographers create and all that nonsense—I want the director to see what I’m trying to do.

BRIDGES: You mean the monitors on set—the film is not as accurate as the video …

DEAKINS: It’s nothing alike.

BRIDGES: I was the guy who talked the Coen brothers into using monitors.

DEAKINS: I know! They were actually quite nervous about it, how it would hold up—after a take, running over to the monitor, watching your take, and then running back as the assistant was putting on the clapper board and then doing the next take.

BRIDGES: Yeah, you learn these little things! And it’s not like watching dailies, where it’s too late. You can use that; you can misuse that, too. You’ve got a video village and all these people around.

DEAKINS: And everyone’s obsessed about it. I think it’s not all technology though; it’s the way you use it, isn’t it? When Steadicam was invented, for instance, everyone was wandering around with a camera, and they would never cut. But in the end, that doesn’t really work.

BRIDGES: What do you think of drones? Did you use drones in Sicario?

DEAKINS: No, we didn’t. We did helicopter work, but not drones. On Prisoners [2013], we did use a kind of drone. I think they’ve really got a place. Again, you can overuse them …

BRIDGES: Right. I just went to a place in town, in Santa Barbara here—the guys are working on the new format, man. It has the mask that you put on and you’re inside the world. Have you used that?

DEAKINS: Yeah, I played with one a while ago. It’s equivalent to working in animation, where you create this virtual world that you can actually work your shots out by putting the glasses on and feeling a virtual set around you. But I’m not sure about it for the experience of film …

BRIDGES: It’s the future of our business. What we do is pretty primitive in a way. You know, 24 frames—that’s about as slow as you can get now.

DEAKINS: Yeah. [laughs] I don’t do that virtual reality stuff. I’m not even into 3-D actually.

BRIDGES: Have you shot in 3-D?

DEAKINS: No, I won’t. I’ve been offered it. I just don’t want to. I think I’m gonna do this film with Denis [Villeneuve] that’ll be made into 3-D eventually, but it won’t be shot in 3-D. I don’t really like watching 3-D. I mean, I’ve worked on a lot of animated movies that were 3-D …

BRIDGES: Those animated films are interesting. It’s so expensive to do it that they rewrite that script over and over, and it takes years to do!

DEAKINS: Yeah, it’s a crazy process. It takes, like, four years. I’ve been working on animated films, not at the moment, but for the last few years, and I do it remotely. So when I was in Australia with Angelina Jolie shooting Unbroken, I was working on this film How to Train Your Dragon 2 at the same time. [laughs] You know, because it’s so slow.

BRIDGES: I just did The Little Prince. I had a great time doing that; it’s a completely different process. So when you go scout a location, where do you start? Do you have a starting place, or is it different every time?

DEAKINS: It’s a little different every time, depending on where the director is coming from, really. With Denis, say, on Sicario, it’s very similar to working with Joel and Ethan—you know, read the script, and then we just generally talk about the script, and it gradually evolves. I like scouting locations with a director when they first look into locations, because I think it’s all-important, if only for that time you spend just discussing the look of the film and ideas about the film.

BRIDGES: You’re aware of the time of day, where the sun’s going to be when you’re shooting and all that?

DEAKINS: I usually go back and study that later. Depending on the scene, sometimes you go back and study it a lot. When we were doing No Country for Old Men [2007], there’s a sequence where Josh Brolin is escaping from the Mexican drug dealers at night, and it becomes dawn, and he’s chased down the river by the dog. It’s a long sequence, and there are a lot of shots, and there are a number of different locations in that. So I probably spent four or five days looking at those locations and studying the light and the angle, and then working out how to shoot that to get some sort of continuity of light over the whole sequence. But that’s not really something you do with a director initially. Initially, you’re talking more about the general look of something and how something might be staged in a location. Like the night work on True Grit, for instance—I went to that location with the gaffer, Chris Napolitano, maybe six, seven, maybe even nine times, studying exactly where we could put lights and the shot angle. That was probably one of the most complicated things I’ve ever done, because you also don’t have much time to do it. All that time you spend in prep saves time when you’re shooting.

BRIDGES: Oh, man, I’ll say. A lot of people don’t really understand what rehearsal’s about. People are afraid they’re gonna leave it in the dressing room, or you’re gonna shoot your wad in rehearsal. [Deakins laughs] When I did [The Morning After, 1986] with Sidney Lumet, for two weeks, we would rehearse the entire movie from beginning to end two times every day. And his direction was, “I don’t want you to indicate how you’re doing; I want full-blown performances every time.” Because that’s how you really get down to it. And it was really helpful telling the story that many times in a linear fashion.

DEAKINS: But what is interesting is that everyone is slightly different.

BRIDGES: Yeah. The one I just finished in New Mexico, our director [David Mackenzie] didn’t have any monitor and no script supervisor!

DEAKINS: Wow.

BRIDGES: But it was kind of rough and ready and gave it a certain excitement, you know? I really enjoyed working with Mackenzie-wonderful director. And he did something that was interesting, where on weekends, he would invite the cast and crew to this little cabin in the middle of Albuquerque, where the film was being edited, and he would show the week’s work. And not that it would be any kind of final thing, but it was interesting bringing together the group, like, “We’re all in this; see what we’re doing together.”

DEAKINS: Yeah, that’s kind of nice. That’s one thing I miss about shooting film. Ever since shooting dailies is gone, people don’t tend to watch dailies together.

BRIDGES: I miss that, too. The camaraderie of that.

DEAKINS: I was always a nervous wreck, but there’s something about everybody getting together. You really felt like a more coherent group of people, you know?

BRIDGES: That’s one of the things I like about our biz is that community, working with all these artists and everybody bringing their best … And that magical thing happens every once in a while where you’ve got high expectations going in, and then the thing will be cut together, and your expectations will be totally transcended.

DEAKINS: Yeah, it’s a wonderful feeling, isn’t it? I get that way on a set when a shot works. Partly why I love to operate is that I love to watch an actor within a shot. When you watch a shot, and you know that everything’s come together, I feel I’m the first person watching it. I always get pleasure out of that.

BRIDGES: Oh, I bet! Do you ever give your two cents when you see a rough cut and say, “Jeez, that other take was better”?

DEAKINS: Yeah. You know, it very much depends on who you’re working with. With Angelina Jolie on Unbroken, I saw a lot of different stages of the cutting because there was a lot of effects work I was working on for that film. So, yeah, I was quite involved in a film like that.

BRIDGES: Do you have a special way that you like to work with a director, and then you work with directors who don’t work that way, who actually work a completely other way?

DEAKINS: I met with Ridley Scott a few times; this was two years ago. I really enjoyed talking to him, but I knew Ridley liked to operate the camera himself. I said to him at the end, “I honestly don’t know how this will work because I like to operate and you like to operate, and I don’t think either of us is gonna change.” [both laugh] So you can’t really force yourself to be somebody you’re not. If it’s somebody you don’t know, and you go into a meeting, you’ve got to feel you can work with them and with their way of working.

BRIDGES: Yeah. I did a movie with Ridley, on the ocean.

DEAKINS: Oh, yeah, White Squall [1996]. The other thing he likes doing is shooting on zoom lenses, and I’m not mad about zoom. [laughs] You know, most of the shoots I do with the boys, we shoot single camera. Sicario, we shot single camera.

BRIDGES: I loved your choice of distance on some of these scenes—you know, that scene where Josh and Emily are talking …

DEAKINS: Oh, yeah, when they’ve come back from Mexico.

BRIDGES: Yeah, it’s kind of far away, but it’s like you’re overhearing them.

DEAKINS: After we shot the shot, I said to Denis, “Should we go in now for overs?” And he said, “No, I don’t want to use it.” He was absolutely adamant. He’s very confident in that way.

BRIDGES: Good.

DEAKINS: I thought that was great. I mean, I loved the shot as it was. Joel and Ethan will do that sometimes. There will be storyboarding on a scene to have a lot of coverage, and we’ll go in in the morning and shoot, like, a two shot, and then I’ll say, “Well, we’ve got the overs now.” And they’ll say, “Well, I don’t think we need them.” [both laugh] They’re also very confident when they feel they’ve got something.

BRIDGES: What was the best advice you were ever given?

DEAKINS: I’ll tell you the worst advice I was ever given. It was when I was leaving the National Film School; there was a very high power producer who said to me, “You’ll never make it. If I were you, I would try to get a job as a PA at the BBC in Plymouth.” And six years later, I was actually shooting a film that he was producer on. I’m not going to mention his name. [both laugh] It always makes me laugh. So I guess I never take anybody’s advice.

BRIDGES: What advice would you have given yourself when you were starting out?

DEAKINS: You know, I always stuck to doing things I really felt something for. I think that’s really important. And actually, that’s the kind of advice I give to students or young people who want to be cinematographers or be in the film industry. I have this website and people write in …

BRIDGES: I saw that. Tell me a little bit about that website.

DEAKINS: Well, I was doing a Q&A years and years ago. I was screening Army of Shadows [1969], directed by Jean-Pierre Melville, which is my favorite movie. After the film, there were literally hundreds of students who came up and asked for advice. And after that evening, my wife said, “Well, we should start a website.” So we decided to start this website if people wanted to ask questions, and it’s become a general conversational site. It’s quite nice, really.

BRIDGES: Wow, cool! That’s inspiring for young guys starting out, to get it right from you. Do you answer questions, or do you do a blog thing?

DEAKINS: I just answer questions. It’s like a forum, really. Some other cinematographers get on it to answer more technical questions because I’m not very technical. [laughs]

BRIDGES: That’s a good thing to do. I’m getting to the same age as you—I’m 65—so I’ve often thought about trying to spread the stuff I’ve gleaned through the years. What else do you have cooking?

DEAKINS: I’m not sure, really. When we come back to L.A. in a few weeks, we’re going to start doing the DI [digital intermediate] on Hail, Caesar!, the Coen brothers movie.

BRIDGES: Oh, man. What’s that about again?

DEAKINS: It’s set in ’50s Hollywood. It’s the story of this fixer producer in a Hollywood studio. And it’s quite funny. So we’re gonna do the timing on that. And then I’m going to be working with Denis again, on Blade Runner [1982]. Well, it’s a follow-up to Blade Runner.

BRIDGES: Oh, great. Is it based on a book?

DEAKINS: No, it’s a script co-written by the same writer who wrote the original Blade Runner, I believe. Or, he wrote part of it. I’ve always wanted to do a really interesting science-fiction piece, so I’m hoping this is it. [laughs] And you? What are you up to?

BRIDGES: Well, I finished that movie in New Mexico a couple months ago. I got another one, this movie called The Emperor’s Children, but the trigger hasn’t been totally pulled yet. I’m hoping it will be. And then I’ve been doing a lot of music; I’ve been touring around with the band and doing that kind of stuff. And what else? Oh, yeah! I just became a grandfather for a second time a couple days ago. So we’re leaping around with all that. [Deakins laughs] And I’m trying to soak up the time I got off here. Well, good to catch up with you. I’m hoping we get to work together again. Maybe with the brothers or something if we’re lucky.

DEAKINS: Yeah, that’d be really good.

JEFF BRIDGES IS AN ACADEMY AWARD-WINNING ACTOR WHO HAS STARRED IN THE BIG LEBOWSKI, CRAZY HEART, AND TRUE GRIT.