New Again: Colin Farrell

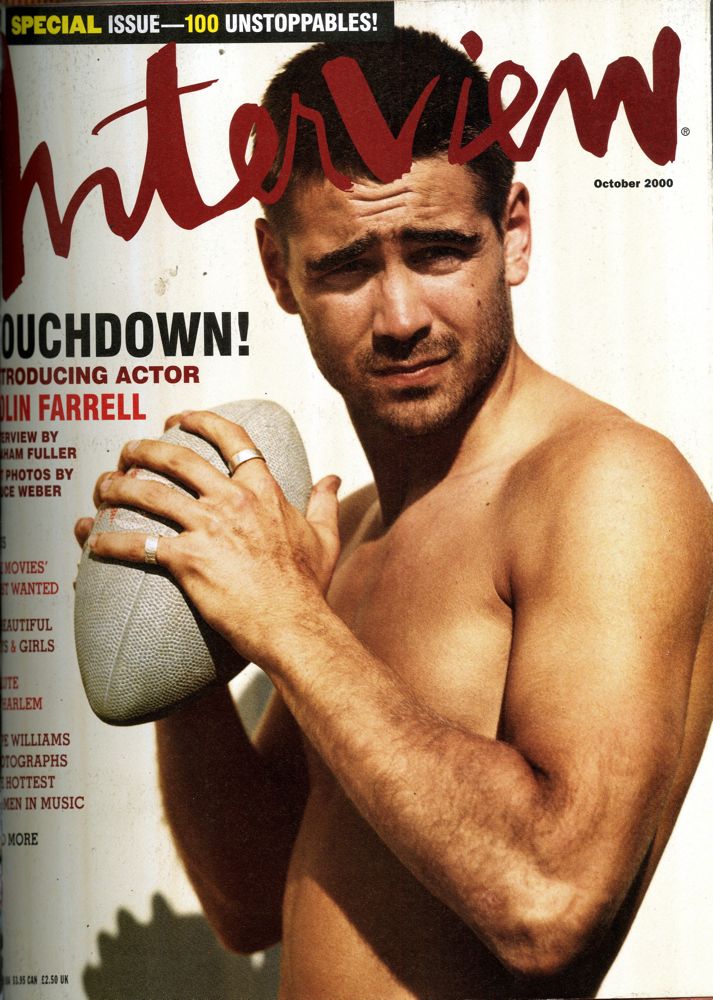

Rumor season is over: Colin Farrell and Vince Vaughn are officially starring in the second season of HBO’s beloved crime drama True Detective. It’s a difficult gig—who could ever replace Woody Harrelson and a post-2010 Matthew McConaughey?—and Vaughn and Farrell have both had some recent career missteps (Winter’s Tale; any movie Vaughn made after 2007). But when the two actors were just starting out—Vaughn in Swingers (1996) and Farrell in Tigerland (2000)—we were excited about both of them. We even put an unknown Farrell on the cover of our October 2000 issue. In the hopes of getting excited again, we’ve reprinted the full interview with the then 24-year-old Farrell below.

Colin Farrell

By Graham Fuller

The movie world just got a big burst of talent, spunk, and liveliness.

Very shortly, Colin Farrell will elicit comparisons to James Dean and the young Robert De Niro. This comparing of one actor to another is a risky business, of course, because no two actors are ever truly alike, any more than any two human beings are. But sometimes the effect a star has reminds us how we felt when we saw another for the first time, usually when the original emotion we experienced came as a bolt of lightning. Like Dean and De Niro, or for that matter Jean Gabin or Humphrey Bogart, Farrell radiates the kind of romantic fatalism that translates into the purest kind of cinematic heroism, charged as it is with longing—his and ours—and the beauty in nobly facing up to failure and disenchantment. I say all of this on the strength of seeing Farrell in his first big part. In the rough-hewn Tigerland, directed by Joel Schumacher, the 24-year-old Dubliner plays a Texan conscript, Bozz, who’s on his way to Vietnam via boot camp at Fort Polk, Louisiana. Insolent, cynical, and disruptive, he gradually finds himself emerging as his training group’s natural leader and as father confessor to those hapless boys—including his naïve buddy Jim Paxton (Matthew Davis)—who would find themselves sitting ducks once “in country.” Unsentimentally, he goes about saving them—but can he save himself?

With his carbon looks, glittering eyes, and unshowy authority, Farrell blazes in the picture. And it’s hard to believe he won’t make a charismatic frontier outlaw in the upcoming Jesse James, directed by Les Mayfield (Warner Bros., 2001). Farrell has the aura of a wild rover—and we haven’t seen one of those for a while.

GRAHAM FULLER: Where are you, Colin?

COLIN FARRELL: I’m in a small place in Texas called Palestine, between Dallas and Houston. I’ve just got in after finishing a long day. It was 106 fucking degrees.

FULLER: And you’re playing the title role in Jesse James?

FARRELL: Yeah. It’s kind of romanticized and takes the legend thing to the furthest level it can to tell a nice story. Hopefully it’ll be an entertaining ride—a lot of action, a bit of a love story, and a bit of a comedy.

FULLER: What’s an Irish lad doing playing Jesse James?

FARRELL: I have no idea. It’s nuts. Nuts! I did the audition before I went back to Dublin, after doing Tigerland, and it went well. I thought, I got a chance to play Jesse James. I’d better take it.

FULLER: Westerns were a dying breed when you were growing up, right?

FARRELL: I didn’t grow up on Westerns as such, but I ran around the garden playin’ with my gun, trying to be Jesse James and Billy the Kid. So now it’s great to be acting with horses and guns and Confederates and Yankees and stuff.

FULLER: You were an unknown quantity over here when you got the lead in Tigerland. So how did it come up?

FARRELL: I read the script in Dublin and I loved all the characters in it. They were just kids—18, 19, 20—who were up against it, and they were so well-defined. You didn’t have to dig deep to answer the question, “How would I have dealt with this if I was in that situation?” It must have been a good time to be in America if you were young—everyone doing acid, smoking dope, dancing, and so on. And yet these guys were in boot camp getting shouted out and beaten up, and they’re going over to Vietnam to fight this war. My character, Bozz, was very aware that America was losing the war and that there wasn’t even a 50-50 chance that you’d survive. The chances were you were gonna come back in a body bag if you came back at all.

FULLER: When you did boot camp before the movie, did the training officers ride roughshod over you?

FARRELL: I was expecting to be roared at and to be called a pillow biter and all that, but it didn’t happen, because it was acting camp, I suppose. But since I was playing Bozz, I had intended to go in and fuck with the guys that were training us.

FULLER: And did you?

FARRELL: No, because, number one, they were too nice. I would have just been a schmuck. And number two, I thought, I have the power, I know how to fuck with people if I want to, so why don’t I spend the next two weeks learning everything I can so if I decide not to do it in the film, at least I know what I’m deciding not to do. The thing about Bozz is he’s a completely capable soldier and could be a very good one if he put his heart into it.

FULLER: Did you identify with his rebelliousness?

FARRELL: I identified with his reaction to being forced to do something against his will and with his trying to break those who are trying to break him. I would never be un-nice to someone unless they were nasty. I don’t give a fuck if someone can’t form a sentence because they’re tanked or don’t have a penny in their pocket and haven’t washed in a year. One thing I won’t tolerate, though, is bullies. I despise them.

FULLER: As someone who could have a big career in Hollywood, you’ll probably have to accept the rules of the institution. That might mean a certain amount of toeing the line and knowing when to hold your tongue. How do you relate to that?

FARRELL: My mother taught me amazing manners. I consider myself—and know I am considered by some people—to be polite. And it’s not about having any hidden agenda; it’s the way I am. I have little time for people who are nice to you because they want you to do something for them. Of course, that’s going to happen, and it’s part of the whole you-scratch-my-back-and-I’ll-scratch-yours cycle. That’s fine—it’s part of the job. I’ve met good people in Los Angeles and I’ve met some assholes. But when I meet good people I stay with them, and the lads in Tigerland are those people.

FULLER: Did you stay in Bozz’s head through the shoot?

FARRELL: No. We’d do the job each day and then we’d cut. We’d go out, get drunk, and we’d laugh. But when we were working I did spend a lot of time chilling on my own, staying in a certain space that I felt Bozz would be in. And it was lonely because Bozz intentionally isolates himself from everyone in the gang. He doesn’t want to be part of the group; he doesn’t want to be a yes-man; he doesn’t want to play by the rules. He thinks it’s ridiculous, which I can identify with.

It’s easy to say it now, but I think I might have reacted the same as Bozz did in 1971 if I’d been his age. No, I’m sure I would have. But he does get pulled into this gang, completely against his will. He can’t help it because of his friendship with Paxton. It’s not where he wants to go, so a lot of the time I was fighting back. There was just no way Paxton was going to make it through the first week in Vietnam, but there’s no telling who would. Joel said to me, “How do you think Bozz did during the war?” And I said, “You know what? I have no idea.” That’s the thing—best soldier in the world, and on the first day he steps on a land mine or gets shot by a sniper. But Bozz has a better chance of surviving there than Paxton, which is why Bozz does what he does.

FULLER: You hear these stories about actors who are antagonistic to each other because they oppose each other in a story. Did that happen?

FARRELL: Absolutely not. We were familiar with each other on a decent level before we decided to hate each other on film, and I think that worked. Shea Whigham, the actor who played Wilson [Bozz’s nemesis] and I had far too much respect for each other and were too much into helping each other out to do anything like that. Although as soon as “Action!” was called, we’d kick the fuck out of each other.

It was tough. Jesus, I was in tears after the eighth take because I was dealing with so much anger. I have a terrible temper and something like that hadn’t happened to me in years, but I had to go in there and do the scene, and it was horrible. But as soon as the scene ended, it was, “How are you? Cool?” We didn’t need any of that other stuff. Acting’s a job, and if you’re an open enough person, you can access certain emotions without letting them bleed into reality.

FULLER: Was Tigerland the first time you did that?

FARRELL: I did a play called In a Little World of Our Own at the Donmar Warehouse in London. I played a 17-year-old-semi-autistic and quite simple kid, who, emotionally, was an open wound. I’d stay in character even when I was offstage, which was tough because he was a nonsmoker.

FULLER: Could you go to war?

FARRELL: If I had to go to war to protect my family, my rights, my home, I would. I’d hate it, but I’d do it, and I’d fight until my last dying breath. But I don’t want to say if the Vietnam War was right or wrong. I have my own ideas about it, but there are too many people that did go that didn’t have a choice, or maybe they did and they thought they were doing right, or maybe they were doing right. It’s too serious for me to make any comments on because I’m Irish.

FULLER: OK. What was you upbringing like?

FARRELL: I’m the youngest of four kids from—I don’t know what [social] class you’d call it. My father played professional football [soccer] for Shamrock Rovers, and I played a lot too. I was good in school for a while, but then it all went downhill. I went to a few different schools, and then got thrown out. There was always a little bit of football, a little bit of trouble. I remember nice summers, watching the World Cup, kissing a girl, getting a feel. Started drinking when I was 14, two or three cans of Budweiser with the local football team I played for. I had a great time.

FULLER: Do you have a good relationship with your parents?

FARRELL: Yeah, Rita and Eamon. I’m doing great with them both. My father works a lot, so I’ve spent more time around my mother. She’s got a heart the size of Texas, man. She just arrived here today, and she’s going to be staying for the last 10 weeks of the Jesse James shoot. It’s such a treat to be able to bring her over. It makes me feel good about myself. But I know if I didn’t have a penny in my pocket I’d be a good son. She needs to be pampered now. She’s worked hard.

FULLER: She might have a movie star son.

FARRELL: [laughs] If I play my cards right.

FULLER: How did you get into acting?

FARRELL: I always wanted to do it. My sister would be up at two o’clock in the morning watching black-and-white movies on TV, and I’d stay up and watch them with her—Hitchcock and stuff. But I was drinking and smoking and getting lazy, and I thought, maybe it’s time to try acting and see if I like it. I did a couple of classes at the National Performing Arts School in Ireland, and I loved it. I find it hard and frustrating as well. I don’t find acting therapeutic and I don’t hide behind it by changing into this person or that person. I don’t deal with y problems through it. It’s just a huge challenge.

FULLER: Does it fulfill a need?

FARRELL: It must fulfill something, but I’m not aware of any void or emptiness. Acting is just a good thing.

FULLER: So what about girls?

FARRELL: Girls are great. We adore girls. Girls are amazing, gorgeous just to cuddle, even.

FULLER: Have you got time for them right now?

FARRELL: Always, yeah. But I haven’t got a girlfriend. I’ve had some sex in the last year, but I miss what I had with my ex-girlfriend. It was lovely when we had it, but now that we don’t it doesn’t keep me up at night. I’m not a needy person and I don’t feel there’s anything missing as such. I’m a big believer; if I meet a girl and fall for her, I’ll do it with all my heart and soul.

FULLER: You want kids?

FARRELL: That’s one thing I can’t wait for. But it’s not for now and it’s not for next year. All the stuff that’s proceeding now will enable me to get to that stage.

FULLER: This is the moment for doing as many films and plays as you can, right?

FARRELL: Absolutely. That’s where I am now, brother.

FULLER: You seem to be in the right place.

FARRELL: Yeah. And it’s taken 24 years and a lot of love from my mother for me to get there.

THIS ARTICLE INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE OCTOBER 2000 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.