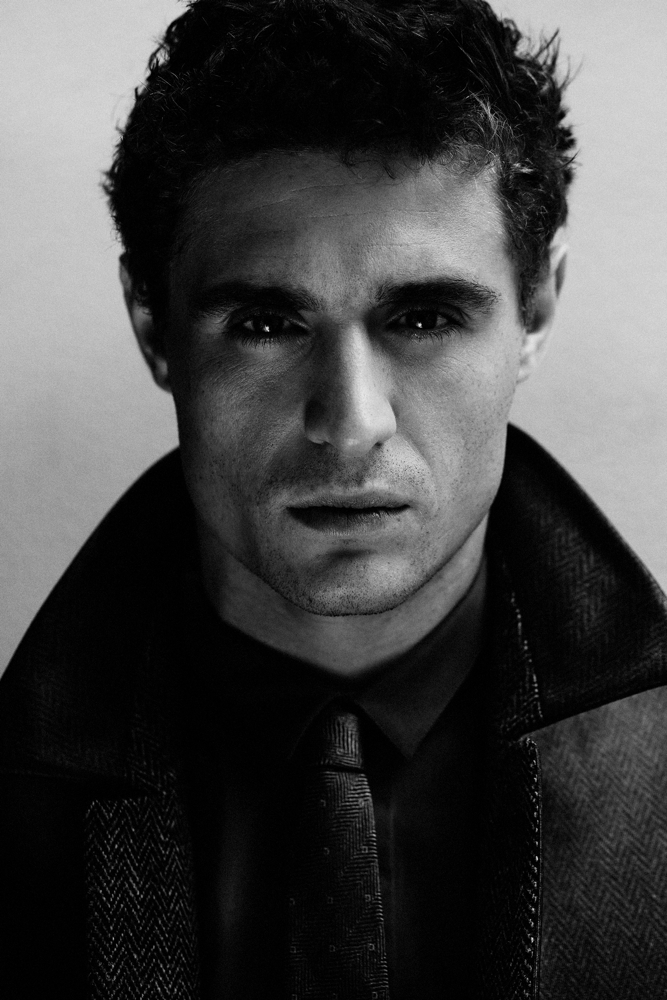

Max Irons Assumes His Throne

PHOTOS: BRIAN HIGBEE. STYLING: JESSICA MARGOLIS. GROOMING: ANNA BERNABE/EXCLUSIVE ARTISTS.

Though you wouldn’t know it from his patient demeanor, Max Irons is tired. The 27-year-old actor has just finished his run as Stephen Bellamy in Beau Willimon’s play Farragut North in London. “He never comes off stage,” he explains. “It was killer, but it was great.” Now Irons is in New York for a few days to see his girlfriend and do press for his finale of his Starz miniseries, The White Queen. “I’ve only known her for five months or so,” says Irons of his girlfriend. “This is the first time I’ve been here with her. I met all of her friends in one go last night.” Was it intimidating? “It was, but then within 10 minutes I thought, ‘No, they’re good people,’ which is nice,” he confides.

The son of British actor Jeremy Irons and Irish actress Sinéad Cusack, Max is tall, gracious, good-looking, and casually charming. In The White Queen, he plays the frequently overlooked 15th century king, Edward IV, as he fights against various members of his kin for the throne of England during the War of the Roses. The maternal grandfather of Henry VIII, Edward is perhaps most famous as the father of Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury, the two preteen “Princes in the Tower” that were murdered by their uncle and immortalized in John Everett Millais’ famous portrait. “They were ruthless,” comments Irons of the time period. “You had to be to stay in control—your own brother is trying to kick you off the throne. You go up to the North of England and come back to find you’ve been replaced by someone else, so you have to be vigilant and very aggressive.”

While The White Queen will air its season finale this weekend, Irons’ work for the year is far from done. The actor recently wrapped an adaptation of Laura Wade’s play Posh with Sam Claflin, Douglas Booth, Holliday Grainger, Jessica Brown Findlay, Natalie Dormer, and Freddie Fox. Next, Irons will head to Ukraine to film The Devil’s Harvest, followed by Keys to the Street, a Ruth Rendell book adapted by Christopher Nolan and costarring Gemma Arterton and Tim Roth (a man Irons dubs “a fucking legend”).

EMMA BROWN: The White Queen moves very quickly. I thought the entire series would cover a few years at most and then within the first few episodes, you already have all of these children.

MAX IRONS: Tell me about it. Towards the end, one of them was older than I was in real life. Edward was a very fertile young man.

BROWN: Edward seems quite forgiving.

IRONS: He was incredibly forgiving. His brother and his best friend and his advisor tried to kill him and then he had them back to court, invited them back. But then again, it’s the same old thing. Allegiances are so important to maintain, because without them you’d be nothing.

BROWN: Do you think it’s more self-serving than it is brotherly love?

IRONS: No, I think there was a bit of brotherly love, but I think everything has a motive when you’re king. It’s all about maintaining that power—securing that power—and I think Edward was very skillful at doing that. I think he was a great king. Opinions are split, if you look at what he’s done and written about him. I think he was a modernizer who was a new thinker. The things he intended to do—unify the country, expand it all from coast to coast—were very modern and radical in those days. Also, the fact that he married who he did and that he managed to deal with the consequences and ramifications of that marriage and stay on the throne until the day he died, that shows skill.

BROWN: Would you have done The White Queen if you knew your character was not going to die?

IRONS: It depends. I was supposed to go up for something recently that was a six-year commitment, and I didn’t want to do it. It was a terrible part as well. I don’t want to be doing six years of something. I’d go crazy.

BROWN: There’s a story about how Dominic West didn’t want to sign a five-year contract for The Wire, and his agent told him not to worry about that because it would definitely get cancelled after a season.

IRONS: Really? Little did he know… he’s with my agent, Dominic West. We have this Christmas party every year. All these young beautiful girls, Dominic West comes in… [whistles] He’s so charming, effortlessly charming, intimidatingly charming.

BROWN: When did you decide you wanted to be an actor?

IRONS: When I was about 16, I did a Neil LaBute play called A Gaggle of Saints from a collection of plays called Bash—very violent story about a young Mormon who goes to Central Park with his friend and beats up a gay guy. But it was the first thing I had ever done, and I thought, “God, this is fun! This is far more fun than anything else I’ve been doing at school. I want to stick with it.”

BROWN: You weren’t in a nativity play when you were four?

IRONS: I tried to be, but I got cast as a tree or something. I was very dyslexic as a kid, so that never helped. When you’re at that age, they just put you on stage and say, “Read this!” and act. I could never do that.

BROWN: No nepotism in primary school?

IRONS: Nepotism is despised in England, which is a very good thing. I think something to do with the class system. People really look down on nepotism. So yeah, it never really works in your favor—even in this industry.

BROWN: Can you tell me a little bit about Posh? Whom do you play?

IRONS: I play Miles, who was played by Kit Harington [in the original play]. It follows two new initiates—Alistair played by Sam Claflin and Miles played by myself—into this world of the Riot Club, a fictitious take on the Bullingdon Club. They’re a nasty bunch of people. The Riot Club’s sole purpose is to celebrate wealth, elitism, hedonism, and excess—just random acts of destruction and chauvinism, which is interesting because our Prime Minister, our Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Mayor of London were are a part of this club. If you think back to the riots we had in London a couple of years ago, they threw the book at these kids who trashed up a few shop windows, stole a few pairs of sneakers. They sent them to jail for three years, branded them publicly, and I quote, as “mindless hooligans.” And you think, Well you were doing the same thing at a more discerning age, being afforded every privilege in life, you to have the ability to pay for the damage you caused, so hopefully, even hopefully, it will ignite that debate. Because if they ever get asked about their time in the Bullingdon Club, all they every say is, “Oh, I was young.” Well, they were young—they were younger and less educated and less privileged and less fortunate in every way, and you branded them for life.

BROWN: Does it still exist?

IRONS: The Bullingdon Club—yeah, they were recently photographed out in Zambia drinking champagne and shooting.

BROWN: How wonderful. Is the club co-ed yet or is it still all male?

IRONS: Oh no, it’s all male. Bullingdon would never go co-ed. I’m not going to give anything away, but there are a couple of girls involved in our story and it doesn’t end well for anyone.

BROWN: Have you ever met Kit Harington?

IRONS: Yes, I have. I think he’s so nice. In fact, when I met Kit Harington first, he was pretty much feeling how I’m feeling today—at a photo shoot and you’ve had no sleep. He was just a really nice, English, down-to-earth guy. No pretense, nothing.

BROWN: He told me an endearing story about how he didn’t realize his name was actually Christopher until he was 12.

IRONS: Really? Well, I couldn’t spell my name until I was eight—my second name. I was so dyslexic. Max I could do. Irons, nope.

BROWN: And you didn’t even try Maximilian?

IRONS: No, and also I don’t want to refer to myself as Maximilian. You’d have to win an Oscar or become mind-numbingly wealthy or hit 50. It’s like smoking a cigar, you know what I mean? You can’t be a young guy and do it.

BROWN: Do you have a 10-year plan?

IRONS: No, I don’t. I want to keep working. I want to step away from young adult fiction. I want to do theater periodically— Farragut North reminded me how great it is. I started out in theater. I trained in theater and then I kind of fell into film and TV. I want to work with interesting artists, talented actors, talented directors, and talented scripts. Not necessarily leading roles. If you look at the careers of Philip Seymour Hoffmann, Paul Giamatti, Meryl Streep, none of them shot up in terms of fame or fortune or recognition, they laid a platform of good, solid work and became better and better. I know I haven’t done it. I’ve done a couple of films, which were intended to go straight up. Thankfully they didn’t. So now, I think that’s what I need to do. I just need to grow as an actor. There was recently a story out that I turned down a role in a major franchise. That’s not true. I refused to audition for it. I didn’t get the part. I didn’t even go in because I thought that the part was just a repackaged version of the parts I played before in these young adult films—sort of moody, masculine, but sensitive and all this kind of thing. It was just a repackaged, rather dull thing. I thought, No, because I might want to quit acting if I do it. There’s no sustenance there. It’s acting by numbers.

BROWN: Did you ever read a young adult novel when you were a young adult?

IRONS: No. What did I read when I was a kid? Just William. Aside from that, I didn’t read in my teens. I don’t read much now. I read the newspapers. I should read more books. Only on holiday do I read books.

BROWN: When is the last time you forgot your lines in a play?

IRONS: About five days ago, six days ago. I corpsed for first time in my life. Somebody behind me sneezed. I thought, “That’s not possible.” And then I thought, “Well, it’s fine. I’m in control,” and then about seven people started laughing. Then I just went on stage for a minute and a half and then completely forgot my lines. It was terrible, but we got a standing ovation after the corpsing. So that was the last time. Aside from that, it doesn’t really happen often.

BROWN: Have you ever gotten stage fright?

IRONS: No. Well, it’s when you’re called to do things that are just you. For example, I presented an award at the BAFTAs a few years ago. I don’t know fucking why, but I did, and that was a million times more frightening than walking on stage in your boxer shorts playing a character. It just is. It’s terrifying. I don’t know why.

BROWN: What about auditioning?

IRONS: Auditioning is a funny one. It’s all about energy. If you walk into a room and the room feels off or the people feel off, that can set you off. If the room is very small. I know which casting directors I should go to, because the place is conducive to doing a good job and the people are conducive and I know the other ones aren’t, in which case I send in a tape.

BROWN: Is there anything that would make you quit acting?

IRONS: I guess if everything went tits up, having no work whatsoever, obviously you have to do something else. At the moment I don’t see myself quitting, but I’m open minded about it. You know those kids on X Factor, and you see them and Simon Cowell goes, “What would you do to be a star?” “I would do everything! I’m born to do this!” I’m not one of those people. I think if something were to come up that really caught my attention in life that became what I wanted to do more than this, then yeah—do it. Fuck it.

BROWN: Do you think you’re born to do anything?

IRONS: I think some people are. I don’t think I am. I always wanted to be a teacher. A bit of me still wants to be a teacher.

BROWN: A drama teacher?

IRONS: No. That’s the only problem. [laughs] I haven’t quite figured that out. I taught kids when I was 19. I went on a gap year to Nepal. I was a sort of director. These kids were 18 to 21, so a little bit older than me, but it was brilliant. It was great.

BROWN: Was it hard to establish your authority as a director over your peers?

IRONS: It fucking was, considering I was the only white guy, tall and lanky, and didn’t speak their language. It took about three months of me trying to establish myself while being thoughtful, but getting a bit of respect and establish that dynamic. But then after three months it was easy. They became my friends. It was great.

BROWN: Do you think you have a thick skin?

IRONS: Yeah, I do actually. I think you have to. There are certain things that cut right to the bone, but as an actor you have to because you get turned down for things all the time. I have a friend who was told he didn’t get a job because he was too hairy. I’ve never heard anything that bad, but you have to get used to that sort of thing.

BROWN: Surely that’s something that can be changed.

IRONS: I know! Get him a razor. It’s done.

BROWN: At least give him the option: “You’re too hairy, if you shave—”

IRONS: “—if you shave, we’ll hire you.” Yeah. I’m quite surprised the agent decided to tell him that. Or just button up your shirt and they’ll never know. [laughs]

BROWN: I thought chest hair was back? What happened?

IRONS: Is it back? Is it? Well I’m fucked. I haven’t got a thing. I could paint them in. Transplants.

THE SEASON FINALE OF THE WHITE QUEEN AIRS THIS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 19, ON STARZ.