Kenneth Anger

MY DREAMS ARE, LIKE, BIG BUDGET, AND MY MOVIES ARE SMALL BUDGET. Kenneth Anger

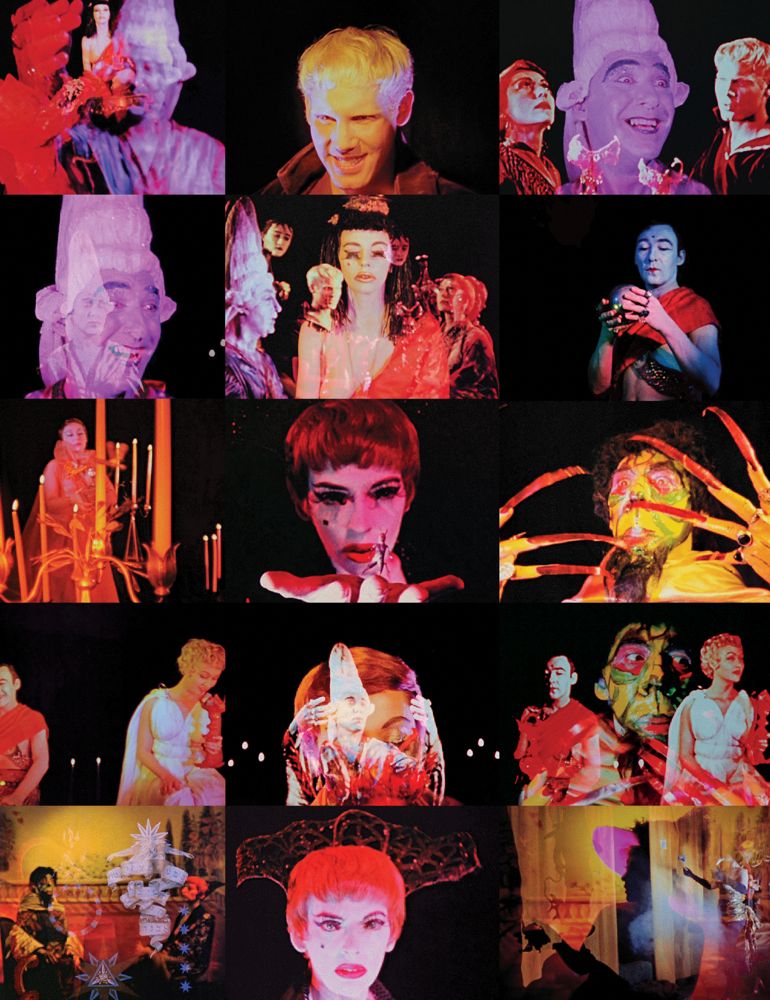

To describe Kenneth Anger as a “cult filmmaker” seems requisite but incomplete. The 87-year-old native Angeleno is indeed the writer and director of the surrealist shorts Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954-66), Scorpio Rising (1963), and Lucifer Rising (1970-81)—some of the wildest and most profoundly influential experimental films of the last century. But his salacious narrative history of the industry, Hollywood Babylon, originally published in 1960, is also kitsch-famous, a kind of gossip gospel in the land of holy celebrity. His film and video works are in the permanent collections of various museums of modern art. And he is also the most famous living practitioner of Thelema—the ritual-based doctrine dictated to Aleister Crowley by the spiritual messenger Aiwass.

Over the course of his multivalent career, Anger has worked with and befriended such artists as Marianne Faithfull (a collaborator on Lucifer Rising), the surrealist Jean Cocteau, guitar god Jimmy Page, sexologist Alfred Kinsey, and Tennessee Williams, as well as fellow Thelemite Marjorie Cameron—star of Pleasure Dome and onetime wife of Jet Propulsion Laboratory founder Jack Parsons. Anger is the godfather of homoerotic cinema, having made his pioneering Fireworks in 1947. He has been famously obscene (and charged as such for Fireworks in California), happily hallucinogenic (his Invocation of My Demon Brother from 1969 was famously evocative of an acid trip), and quite consciously provocative (see all). Inside the industry, he’s never found a place to rest—he has Lucifer tatted on his chest. And he’s seen UFOs—three times.

Painter and filmmaker—and something of a hell-raiser himself—Harmony Korine has long appreciated the work and legend of Anger, but the two have never really had the chance to speak. We thought they should, so in April, Korine called Anger from his home in Nashville to discover that his hero is still working outside of the mainstream, still a scabrous critic of Hollywood, and still speculating about that Malaysia Airlines flight.

HARMONY KORINE: Hi, Kenneth! How’s it going?

KENNETH ANGER: Pretty well.

KORINE: What’s a typical day for you now?

ANGER: I greet the sun in the morning, because that’s part of my religion, and then I proceed with the day.

KORINE: What’s the greeting of the sun like?

ANGER: Oh, it’s just a mental thing. It’s called Liber Resh. It’s an [Aleister] Crowley ritual, where you say, “Hail, hail!” to the sun.

KORINE: Is there anything you say at night before you go to bed?

ANGER: I’m usually up all night. So that doesn’t count.

KORINE: Where are you living now?

ANGER: I live right in the center of Hollywood.

KORINE: Do you feel like there’s any type of magic to Los Angeles still? Is it as interesting as old Hollywood?

ANGER: Uh, no. [laughs] I hate to say that, but the past was much more fascinating. I don’t particularly care for any of the current crop of actors. I don’t particularly care for any of the current crop of directors. But I have a lot of friends who are editors, and there are a lot of technical things going on here that are interesting.

KORINE: How do you think California has changed since you were young?

ANGER: Well, everything is constantly evolving and changing. That’s what life is all about. But basically Hollywood has lost its focus as a film center. Films are now made all over the world.

KORINE: The occult and old Hollywood have played a big part in your work. Is there any kind of crossover between them? What was the energy that connected the two of them, for you?

ANGER: Well, I’m sorry, I really can’t answer that.

KORINE: Okay. Do you practice any religion today?

ANGER: I’m a Thelemite. I believe in Thelema, which is Crowley’s so-called religion. There are some practitioners here who do something called the Gnostic Mass. I’ve been to that a few times, but basically, I’m a loner. I don’t really need other people.

KORINE: What about your dreams? Can you remember your dreams?

ANGER: I try to remember them, and occasionally I’ll make a note or two in a notebook if it’s something extra interesting. They do mean quite a lot to me, and they don’t happen all that often. In other words, I don’t have some kind of loud, Technicolor dream every night. But a few times a month, I’ll have a rather interesting dream. They’re mostly visual—oddly enough, I don’t have much dialogue in my dreams. They just don’t speak. [laughs]

KORINE: Are there things that you’ve dreamed that have ended up in your films?

ANGER: I wish. But my dreams are, like, big budget, and my movies are small budget.

KORINE: [laughs] What if you had no budgetary limitations? What would you make?

I DON’T SEE ANY GREAT DREAM MYSTICS who ARE PUSHING MAGICAL EFFECTS. IT’S TOO BAD, BECAUSE the MONEY IS THERE. But WHERE’S THE IMAGINATION? Kenneth Anger

ANGER: Well, I had to tailor my dreams to fit my budgets. Except in a few cases, like when Sir Paul Getty was alive and he sponsored my Mickey Mouse film [Mouse Heaven, 2004], I had very limited financial resources. So that has dictated my product. With Rabbit’s Moon [1950-79], I was helped by the Cinémathèque Française. They gave me the 35mm film to make it. It was the same film that [Jean] Cocteau used for Beauty and the Beast—the same 35mm negative. I had plans to do a film based on Les Chants de Maldoror by Lautréamont. I did film part of it with one of the ballet groups in France. I made platforms just below the surface of the water; there were, like, tables, they were held down so they wouldn’t float away. So it appeared that the dancers were actually dancing on the water. It’s not a very special effect, because if you had the money, you could do it with people dancing in the air if you wanted.

KORINE: I’d heard that you’d done peyote a couple times, and I was wondering if you still experiment with any drugs.

ANGER: That is in the distant past, and I don’t care to discuss it really.

KORINE: What are you working on these days?

ANGER: I always have a project going on some level. My most recent is Airship [2010-12], using archival footage of the old zeppelins.

KORINE: Wow, of the zeppelin on fire?

ANGER: The last part is with the fire, and then I hand-tinted it orange and red. The only real footage of it was black and white, and the spectacular thing about the end of the zeppelins—because that finished them off—was this incredible fire.

KORINE: Is there any audio to go with it?

ANGER: An atomic explosion—just explosive effects. I listened to several different kinds of explosions, but I like atomic ones best.

KORINE: I’d love to see that. Do you still watch films?

ANGER: I have no reason not to. I mean, I do a lot of reading, too. But I live very close to the Egyptian Theatre, which has revivals of wonderful older films. So I see more of them than I do of new films.

KORINE: Were you a W.C. Fields fan?

ANGER: Yeah. I’ve always liked him.

KORINE: What about the Marx Brothers?

ANGER: Sure. Gleeful chaos.

KORINE: Can you tell me about what it was like being an actor as a kid in Hollywood?

ANGER: I really had just a brief experience of that, which came about through my grandmother, who had been a costumer for silent films. I had a nonspeaking part in A Midsummer Night’s Dream [1935] by Max Reinhardt [and William Dieterle]. My grandmother was a friend of Reinhardt’s.

KORINE: I’ve seen that amazing still of you in the movie—that’s great. Did you really want to be an actor?

ANGER: No. Midsummer was a pleasant experience, but the thing I liked about it was the set on Warner Brothers’ largest soundstage, this forest that was made to glitter. The whole thing was sprayed with shellac. It was very pungent under the lights.

KORINE: How did your book projects, like Hollywood Babylon, affect your filmmaking? Was there any type of crossover to projects like Invocation of My Demon Brother?

ANGER: Well, I’ve always been interested in the Hollywood history. Basically, that is my interest. And then I’ve always made silent films with music for accompaniment.

KORINE: Your movies are so beautiful, dreamy, and otherworldly. I feel like they’re a part of you. What comes first: the stories, or the images, sounds, and colors?

ANGER: It’s definitely images. And a flow of patterns. I call them cinepoems. They’re a form of poetry, only it’s visual.

KORINE: Is there a logic to them, or is it more just a feeling?

ANGER: [laughs] I suppose there’s logic to them. I don’t put in visual material that doesn’t have a direct connection with the kind of dreamlike plotline.

KORINE: Do you approach all the movies in the same way?

ANGER: Yeah, that’s Kenneth Anger’s approach.

KORINE: You’ve lived through all these different eras. Was there any one time that you felt the most kind of attuned to or look back on with the most fondness?

ANGER: Unfortunately for me, the period I was most interested in happened before my time. The 1920s was, to me, a rich period of invention—the so-called Jazz Age—it was always very appealing to me.

KORINE: What did you think about the hippie movement when it was going on?

ANGER: I thought it was kind of fun. I never really identified with it, but I wasn’t antagonistic to them.

KORINE: Was there any one person, any great love in your life who stood out from everyone else?

ANGER: Unfortunately, no. The famous Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey—

KORINE: The sexologist.

ANGER: Yes, he was an extraordinary man. I was his guide in Europe. He died very young, at 62. But a year before he died, he came to Europe and I ended up taking him to Sicily so he could see the ruins from the Abbey of Thelema, which was created by Aleister Crowley in 1920. It was Crowley’s la chambre des cauchemars, the room of nightmares, full of paintings that were both very witty and fun. It was clear that he had a macabre sense of humor. And it’s pronounced Crow-ley. It actually means the shield of the crows, of ravens. [laughs] L-E-Y, means shield.

KORINE: And what was your relationship with Kinsey? Was he a fan of your movies?

ANGER: He must have been, because he bought copies [of Fireworks] for the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University. And he invited me there and interviewed me for four hours. I contributed photographs and material for the collection, which is still there; the Anger Collection at Indiana University is very important.

KORINE: Of all the actors from the past, was there one that you had a fondness for?

ANGER: Well, no. The one actor I admired, just because he had tremendous magnetism, was Rudolph Valentino. And he died very young, at 31. I could have imaged working with him—but, again, he was of the silent period before my time. I just missed him. There are a lot of actors from the silent period that I admire, like Douglas Fairbanks. He was wonderfully athletic and expressed his characters almost in dance, rather than speech.

KORINE: In your movies, too, it’s so much more about the physicality of the actors or the performers. Do you think of filmmaking as a kind of magic?

ANGER: It can be. It can create a kind of trance effect, so I prefer to think of it as a magic possibility. It also can be totally stupid, and a waste of a tremendous amount of money—in the act of being commercial.

THE MARVELOUS THING ABOUT the [UFO] WE SAW WAS THAT IT WAS totally SILENT… I’M WAITING FOR THEM TO COME BACK. But MAYBE THEY FINISHED WHAT THEY HAD TO DO HERE. Kenneth Anger

KORINE: Is there a way to push films in a way that’s maybe even more sensory or more physical? More hallucinatory?

ANGER: I wish. [laughs] I’m waiting for it. I don’t see any great dream mystics who are pushing magical effects. It’s too bad, because the money is there. But where’s the imagination?

KORINE: What do you think happened to that plane in Malaysia?

ANGER: Well, planes disappear all the time. It went down in very deep water, and I don’t think they’ll ever find it. And what’s the point? I mean, everyone on board died—because that’s what happens when a plane goes down like that. I think we should move on. I don’t see what the point is of these tremendous efforts to locate it several miles beneath the waves.

KORINE: It’s hard to imagine what exactly happened.

ANGER: I think that’s interesting. I mean, was it hijacked? Probably, because why would it reverse? If it’s supposed to go to China, why would it reverse direction and head off the opposite way? Well, obviously there was a criminal act aboard.

KORINE: Are there any projects that you wanted to make that you feel like you haven’t gotten a chance to make?

ANGER: There are a lot of things that I would have done if I’d had an adequate budget available. For a time, I had one of the richest men in the world as my sponsor, Sir Paul Getty. He was also was very fond of Mickey Mouse. So I made Mouse Heaven for him. But he’s no longer with us. He died at age 70.

KORINE: What’s your feeling on Disney, the man?

ANGER: Walt Disney? He was a grabber of power, but he also had some very admirable qualities. So it was a mixture. I suppose we’re all mixtures. But in his case, it was a bit of like a Jekyll-and-Hyde thing. I loved some of his early films, but then he sort of got distracted by Disneyland. He always wanted to make some sort of place like Disneyland, and there was a rumor that he planned to take over Catalina Island. But it was owned by the Wrigley chewing gum family, and they wouldn’t do a deal with him.

KORINE: Wow.

ANGER: But the idea of taking your boat to an island where the whole thing is an amazing place—it’s an interesting idea.

KORINE: Did you like the original Disney cartoons?

ANGER: Disney had a genius working for him named Ub Iwerks. Iwerks designed the early Mickey Mouse as just this series of circles. But of course, Disney got credit for it. [laughs]

KORINE: Have you ever had any experiences with aliens? UFOs?

ANGER: Oh, I had three very good sightings. I guess you have to call that an experience. In one case I was with three people, so it wasn’t just me who saw it. It was at the beach in San Francisco, near the Cliff House. We were there in the early morning and a round shape came up off the horizon and flew right over it.

KORINE: Whoa!

ANGER: It wasn’t just me. Three people saw it. It was completely quiet. In any commercial films where they try to have a saucer, they ridiculously put in a bunch of humming noises. The marvelous thing about the one we saw was it was totally silent. There was no sound whatsoever. When it flew over, you could see into a large oval window and, in there, there was some kind of flashing, pure color. It went from a red to green—like an emerald green from a ruby red—and flashed on and off. It seemed like that color had something to do with the way the craft operated. I had two or three other sightings in England when I was there. Again I wasn’t the only person to see them. They were seen by people in Scotland and England at the time. I’m waiting for them to come back. But maybe they finished what they had to do here, and their little visits to planet Earth are over.

KORINE: What do you think happens when we die?

ANGER: Well, we’ll find out. Either it’s just a black curtain … I mean, life is interesting enough. You don’t need something after. It’d be nice if there is—nearly all the cultures imagine some kind of heaven, but it could just be wishful thinking. Then, to counter the heaven, they’ve imaged a hell. And often the hell thing is more interesting. [laughs]

KORINE: Very true.

ANGER: It’s been good talking with you.

KORINE: Thank you so much. You’re a great hero. I’ll come see you when I come out to Los Angeles.

ANGER: I look forward to seeing you.

HARMONY KORINE IS AN ARTIST, SCREENWRITER, AUTHOR, AND DIRECTOR. HIS FILMS INCLUDE SPRING BREAKERS, MISTER LONELY, AND GUMMO.