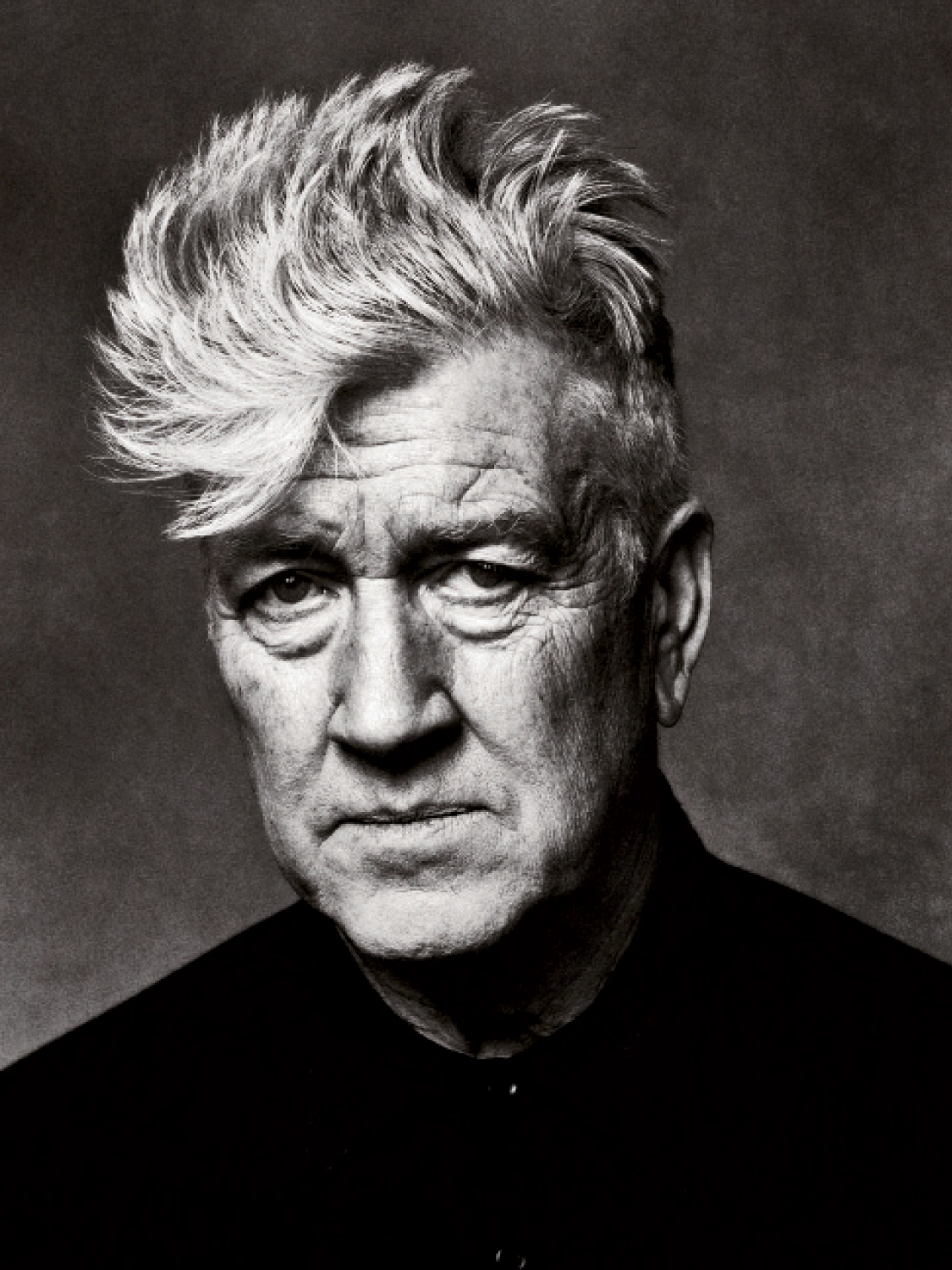

David Lynch

Ideas are like fish. They just come to you sometimes…David Lynch

David Lynch, of course, is best known as the vanguard director of dreamlike and disturbingly allegorical films such as Eraserhead (1977), The Elephant Man (1980), Blue Velvet (1986), and Mulholland Drive (2001)—movies that are as idiosyncratic and independently spirited as movies come, yet consistently flirt with a kind of mainstream Americana. Films like Wild at Heart (1990) and Lost Highway (1997) teem with sex and violence that is anything but cartoonish, while Lynch’s heartland tale, The Straight Story (1999), proved clean enough to earn a G rating. He has consistently coaxed vivid, career-defining performances out of his female leads, including Isabella Rossellini, Laura Dern, and Sherilyn Fenn. In 1990, well before shows like The Sopranos or Mad Men transformed series television into a creative hotbed, Lynch revolutionized the medium with Twin Peaks, a stark, surreal serial about the investigation into the death of a homecoming queen in a small town in Washington. He was also an early adopter of the Internet as a forum for creative work, producing a set of online shorts dubbed Dumbland, as well as a sitcom, Rabbits, about a family of humanoid bunnies.

Lynch’s career, though, has, in many ways, embodied the great dichotomies in his work. As a director, his characters are almost neoclassical, wholesome archetypes that one might find in the movies of the ’50s and ’60s by directors like Nicholas Ray and Billy Wilder; yet his films are also uncompromising explorations of the societal id and the dark underside of American dreaming. And as much as he has created within the confines of popular culture, he has continued to be an outlier; he has been nominated for three Academy Awards for directing—most recently in 2001 for Mulholland Drive, for which he won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and which helped launch the career of yet another of his leading ladies, Naomi Watts—then, just five years later, he opted to self-distribute his next film, Inland Empire (2006).

Although Lynch hasn’t put out a feature film in more than half a decade, he has hardly been idle. He began his creative life in Missoula, Montana, as a painter, and recently compiled Works on Paper (Steidl), a career-spanning monograph of his wide-ranging output as a visual artist. Renowned for his meticulous sound design and the innovative use of music in his movies, Lynch also released his critically acclaimed first solo album as a musician and singer, Crazy Clown Time (Sunday Best), late last year, which followed his musical and visual collaboration with Danger Mouse and Sparklehorse on the 2010 album Dark Night of the Soul. (In addition, he worked with Interpol via the Creators Project on a short film shown at the Coachella music festival last spring.) Lynch has also added interior designer to his wide-ranging résumé, helping to conceive of and create the decor of the semiprivate club Silencio in Paris, which opened last year.

In conversation, the 66-year-old Lynch proves to be a living, breathing analog to his art: a beguiling combination of the cosmic and the mundane, the surreal and an abnormally normal-seeming normal. We spoke in Los Angeles, where Lynch lives.

MATT DIEHL: I’ve noticed a thread throughout your recent activity. You’ve made a new album, you helped put together a new nightclub, you have the comprehensive Works on Paper book that brings together all the strands of your visual art, you’ve taken film distribution into your own hands. Adultery is something of a prominent theme in your films, and you currently seem to be in a moment of creative promiscuity, philandering between genres and mediums.

DAVID LYNCH: [laughs] Right. You know, I’ve always said cinema combines so many different art forms. As a kid, I was always building things. My father had a shop in the house, and we built things—we were kind of a project family. I started out as a painter, and then painting led to cinema, and in cinema, you get to build so many things, or help build them. Then cinema led to so many different areas—it led to still photography, music . . . Furniture is also a big love of mine. I started building these kind of sculptural lamps. Then I got into lithography at this printing place in Madison, Wisconsin, called Tandem Press. For the last four years, I’ve been working on lithography in Paris at a great, great printing studio called Idem. And I’ve always been painting along the way, as well as doing drawings and watercolors . . . There are just so many things out there for us to do.

DIEHL: As I understand it, when you originally got into film, it was to try to make your paintings move. Is that correct?

LYNCH: Yes. I wanted to make a moving painting.

DIEHL: It’s funny because I recently watched The Alphabet [1968], one of the early shorts that you made in art school, and it reminded me exactly of that: it was as if a Francis Bacon painting had come to life.

The films don’t make a peaceful world violent—-the violent world made the films.David Lynch

LYNCH: Ah, well, Francis Bacon is one of my giant inspirations. I just love him to pieces.

DIEHL: Speaking of inspirations, the members-only nightclub you recently opened in Paris, Silencio, was inspired by the fictional nightclub in Mulholland Drive, wasn’t it?

LYNCH: The name was inspired by it, but not the actual club itself. What happened was, they asked me if I wanted to help design this club in Paris. It was a strange place—it was way underground and the space was fairly small. But now the club seems very big—it seems a lot bigger than it did when I first saw it. I designed the walls, floor, and ceilings. In this one particular room, the walls curve into the ceiling. My whole idea was to make a place that you felt good being in. I designed many different things—the stage and the movie theater, which is spectacular. You can go from hearing the loudest music into this very beautiful, comfortable theater to watch a film. I also designed what they call a “yellow forest”: it’s a smoking room in the club, with these steel yellow trees that go from floor to ceiling with these little lights coming off them, with pods that you can sit on. It was important to me that everything feel very warm, so we created this wall treatment out of wood blocks covered in different types of gold, which catches light in a really beautiful way. I’m real happy with that. I also designed this sink for the restrooms—I’m really happy with that sink. These things, you just don’t know what’s going to come next. It’s great to be given the possibility of designing a sink; ideas start coming that you never thought about before. A person doesn’t really think too much about a sink, but when you do, ideas come that are really beautiful. So the club has a great feeling now. It’s very beautiful to be inside this club, Silencio.

DIEHL: From what I understand, the location of Silencio is historical. The building, on the rue Montmartre, was designed by the creators of the Eiffel Tower.

LYNCH: I don’t know the whole history of it, but there’s metalwork in there that would make you think of the Eiffel Tower.

DIEHL: Since it opened last October, Silencio has hosted performances by the likes of The Kills, Lykke Li, and parties for Kanye West and Chanel, among other events. The New York Times wrote that “it has been compared to the Dadaists’ Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Andy Warhol’s Factory in New York, and the existentialists’ Café Flore on the Left Bank.” It seems intended to be a kind of hub for new bohemian culture. When I first heard about it, it reminded me of the golden age of New York City nightlife, where you had places like the Mudd Club, where you had all of these disparate people—artists, professionals, people with money, people with no money—meet and exist in the same space.

LYNCH: Well, I don’t know about bohemian . . . It’s a club that people have a good time in. I’m not sure who the clients are all the time, although they seem to be a good bunch. But Arnaud [Frisch], the owner—that’s what his whole wish was, that Silencio would be a meeting place for all different types of people. That’s the feeling it has. Paris is now the second-best city in the world for me. The French have been my great friends, and they believe in a director having final cut. They don’t understand any other way. They protect the artist.

DIEHL: You’ve always been considered an auteur as a filmmaker, but it seems like you’ve become an auteur of many things. I heard that you now even have your own brand of coffee beans.

LYNCH: That came about with these two guys I work with, Eric and Erik. I hate making coffee, but one of them started getting heavy into making signature designs on the foam of the cappuccinos, and then the other started telling me I should have my own brand of coffee. So one thing led to another, and it happened.

DIEHL: You make sinks, you make coffee—is it possible that you might someday have a kind of David Lynch version of IKEA, where everything necessary for everyday life is created with your vision?

LYNCH: No, no—I’m not doing that! I’d have to quit everything and just design away . . . But it would be kind of fun.

DIEHL: You’ve been making music for years, starting with the soundtrack to Eraserhead. But last year you released your first proper solo album, Crazy Clown Time.

LYNCH: Right. I worked on that with my friend and engineer “Big” Dean Hurley. We pretty much did everything together except for the track “Pinky’s Dream,” which we did with Karen O.

DIEHL: Many tracks on Crazy Clown Time have a surprising dance-music influence. A lot of them would weirdly work in a DJ set at a club.

LYNCH: My music agent, Brian Loucks, always brings people up for a coffee, then we talk, and then sometimes it forms into a collaboration. Brian has brought up some great people over the years. So I had been working on music, and one of the first people Brian was going to bring up to meet about it was into dance music. After that, I started thinking about dance music, and all of a sudden some lyrics and a little tune came. The next day, Dean and I started working, and out came the song “Good Day Today.” We played it for Brian, who loved it, and he gave it to Jason Bentley [music director of Los Angeles radio station KCRW], and the story goes that Jason thought the song was by Underworld.

When a certain girl and a certain guy get together, certain things are going to happen.David Lynch

DIEHL: I heard that as it was happening. He played “Good Day Today” on his radio show and introduced it as the new Underworld single.

LYNCH: Not only did he play it on the radio, but Jason took it to Ibiza and played it for two guys named Ben Turner and Rob da Bank. They liked it so much, they said, “We want to put this out on our label, Sunday Best.” It’s a tiny company, but they got that music out in a big, big way. Then they came to me and said, “We’d love to do an album. Do you have more songs?” And we had a bunch, and that’s what became Crazy Clown Time.

DIEHL: Where did the title come from?

LYNCH: The title came from the song “Crazy Clown Time.” The lyrics tell a story of the time . . . It’s a traditional backyard story that involves girls and guys and beer.

DIEHL: In addition to the club grooves, many of the songs are deeply rooted in the blues tradition. What do the blues mean to you?

LYNCH: Well, I love the dirty, rough-running power of the blues-based electric guitar. I like the idea of a gasoline-powered guitar, where you’ve got an accelerator, and you can push down on it and it just revs up. The great blues music is very simple, but sophisticatedly so. It’s so beautiful, this world that the great blues men and women conjured up. It’s got such a mood and a way of moving, and that was a big inspiration.

DIEHL: I know you were initially drawn to art by expressionist painters like Oskar Kokoschka and Francis Bacon, who in a weird way were doing a kind of European, visual expression of blues emotion.

LYNCH: That’s exactly right. There are so many similarities between the blues and a lot of painting.

DIEHL: I was also intrigued by Karen O’s appearance on the record. That’s the only outside collaboration on the album, and the only song that you don’t sing. How did that come about?

LYNCH: Several years ago, Brian introduced me to Karen O. On that trip, nothing happened, but then last year, Karen O appeared again. She came in, and I gave her the lyrics, then she listened to the track over and over. She kind of sat there, you know, thinking, going over things in her mind. It was quite a comfortable situation. Then, at a certain point, Karen went into the booth and knocked the song out of the park.

DIEHL: Had you known about Karen O’s work with the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and her other music?

LYNCH: Sure, but I felt like this was kind of its own thing. The way Karen O says the word pinky, it brings Pinky, as a character, alive. Pinky was in my mind, but not as good as that. Karen made Pinky a character that you kind of know and really care for.

DIEHL: You have a sort of magic with female characters. I found it kind of genius that you included that feminine energy in there. Karen O serves as a kind of presence in your music the way, say, Naomi Watts in Mulholland Drive or Laura Dern in Wild at Heart exist as the heroines and femme fatales of your films.

LYNCH: Yes, you’re onto something. [laughs] Well, there are different types of music, and sometimes Dean and I will do a track and we know right away it’s not for us–that it’s gonna go to some girl because it’s just that kind of thing. I also work on music with this other girl, Chrysta Bell, and she’s a real leading lady. She’s gonna be big, I hope, one day soon. But I love women. I can kind of sit and go into a world where the women . . . Talk to me.

DIEHL: Jean-Luc Godard once said, “All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun.”

LYNCH: Nope, you don’t need much more than that.

DIEHL: The tagline to your last film, Inland Empire, was “A woman in trouble,” which I also thought could be the tagline to many of your films. In so many of them, the women become the emotional pivot for the action.

LYNCH: There are men and women in the world, and they’re different in many ways. It’s really beautiful and interesting when the two meet. When a certain girl and a certain guy get together, certain things are going to happen. It’s always these combos and different characters coming together in a story that make certain things happen. These things are what kind of makes it, and the women play a huge role.

DIEHL: It’s interesting because there are frequent connections between the way some of the women look in your films—that sort of ’50s- or ’60s-inspired, all-American aesthetic—and what’s going on in contemporary fashion. I remember those hairstyles and jewel tones from Blue Velvet suddenly became a look, as did the extreme rockabilly style in Wild at Heart. Prada’s Spring 2012 collection really echoes the way some of your characters dress. A couple of years ago, I know that you also made a short film, Lady Blue Shanghai, for Dior starring Marion Cotillard. We know that your work has been an influence on fashion, but does fashion play a role in your work?

LYNCH: Well, the women dress a certain way for my films, for the world. I want to say one thing about that look: I work with this woman, Patricia Norris, with whom I started working on The Elephant Man. I loved the ’50s and early ’60s and that sort of started the style of Blue Velvet, but Patty deserves all the credit for the way people dressed in it. She has a knack for putting clothes on people that really fit them in every way. The way she dressed Dennis Hopper, too . . . Well, the way she dressed everybody was perfect, and it has to be. If that part of the movie is wrong, then it’ll jump out and bite you.

DIEHL: You’re known for having so many key long-standing collaborators, like Laura Dern, Kyle MacLachlan, and the late Jack Nance, for example. You’ve also transformed people’s careers at unlikely moments, like Dennis Hopper [in Blue Velvet] and Robert Blake [in Lost Highway]. How do you choose whom to work with?

LYNCH: There are so many people I’ve loved working with, but you’ve got to get the right person for the project. Sometimes a person can be your dearest friend, but there’s just not a role for them in the next film. That’s kind of a hardship. If they’re right for the part, though, you rejoice, because you not only love this person, but you’ve worked with them before and developed a shorthand. It’s a beautiful ride.

DIEHL: There’s a song that you sing on the soundtrack to Inland Empire . . .

LYNCH: That’s the song “Ghost of Love.” I had sung before that, but that one is where I got more comfortable. That song, I really love. It did start something . . .

You have to have final cut–you absolutely have to have it. Otherwise, you’re gonna die.David Lynch

DIEHL: At one point while watching Inland Empire, I realized that I was watching a movie conceived by David Lynch, with a song sung by David Lynch, over a scene conceived by David Lynch. It was like full immersion, visually and aurally, in that moment.

LYNCH: That’s beautiful.

DIEHL: And then on top of that, I learned that you self-released the film. You took charge of every aspect of that movie, from its creation to its distribution.

LYNCH: Well, everybody knows that the art houses are pretty much gone. It’s the mainstream films that get the theaters now, and theaters can’t survive if nobody’s coming to them, so it’s big advertising and big money that talks. We didn’t have the big money, so we figured that if we could go and book theaters and do it on our own, then it might be the best way. I don’t know if it was, but that’s what happened with Inland Empire.

DIEHL: In your best-selling memoir, Catching the Big Fish, you say, “For me, film is dead.”

LYNCH: I meant that celluloid, the actual film that runs through the camera, is dead. That’s gone, and now digital is here. But storytelling with cinema never will die—ever, ever, ever. The way the stories are told may change, but it will always be.

DIEHL: It might, though, be the death of film as a director’s medium, where the artist gets final cut. It’s interesting how so many filmmakers with established oeuvres and visionaries who have changed how we perceive cinema—people like you, John Waters, Gus Van Sant, and even Martin Scorsese—often still struggle to set up projects today.

LYNCH: Thousands of other filmmakers out there would agree with that. The studios are superreluctant to give final cut. They have so much money riding on these things, so they want a committee to go and rule the roost. The poor director just dies a death. More and more, when a committee at a studio sees something that maybe people won’t understand, they’ll kill the thing quickly. It’s an insult. I don’t know why anyone would make a film if they couldn’t make the film they wanted to make with all the freedom and the support they needed. But it happens every day, so you have to be independent. You have to not only find enough money to make the film, but you have to have final cut—you absolutely have to have it. Otherwise, you’re gonna die. But there’s always a way. Sometimes restrictions are a big blessing. When you have to build something yourself, ideas start coming that never would’ve come otherwise. New ideas flow in. Happy accidents do occur.

DIEHL: With Inland Empire, you seemed liberated to run with your vision like never before.

LYNCH: Well, it’s a very big freedom to have lightweight equipment and a smaller crew. The pressure is so much less. Pressure equates to money, so it’s really, in a way, a blessing to go low budget.

DIEHL: Mulholland Drive started out as a TV pilot at first. But when that failed, it actually opened the door for it to become a theatrical film.

LYNCH: It was a closed-ended pilot, and then the ideas came to make it into a feature. I was meditating, and all these ideas just flowed in, in one meditation— all the ideas to finish that into a feature.

DIEHL: You’re a devotee of Transcendental Meditation, which you’ve practiced for more than three decades. What does it do for you?

LYNCH: Well, you’re swimming in the transcendent twice a day, and when you swim there, the world gets bigger, and you get wet with that, and the creativity grows. The Beatles, who did Transcendental Meditation, always talked about how the ideas for all those great songs came to them when they were working with the Maharishi. I always say it’s not Transcendental Meditation that does it, but the great treasury within—the great field at the base of all matter and mind. But you need to transcend to get to that field. People have a lot of different, strange ideas of what meditation is. I meet people who say, “My form of meditation is jogging,” or “I lay in the sun. That’s my form of meditation.” But that’s not meditation. You need a mental technique that truly gets you to a field that is beyond the field of relativity. The key word is transcend. Transcendental Meditation is like a key that opens the door to that deepest level of life, that ocean of pure consciousness.

DIEHL: You’ve said meditation helped you in the making of The Elephant Man, which was really your breakthrough film.

LYNCH: Meditation does open up a kind of an understanding that grows. The Elephant Man was such a gift to me. I was a kid from Missoula, Montana, who had made one film at that point that was considered very strange by most people, and here I was in London, England, making a Victorian drama with some of the greatest actors in the world; a lot of people thought I was really not right for that job. One day, I was standing in a derelict hospital in East London, long since it was a working hospital. The halls had the remnants of gas lamps, and it was filled with pigeon shit and broken windows. Then a wind came and kind of blew through me, and I suddenly knew exactly what it was to be alive at that time. Once I got that feeling, no one could take it away from me. I kind of owned it after that.

DIEHL: We live in a moment where violence is pervasive in pop culture. When you made films like Wild at Heart and Lost Highway, you came under fire for the graphic depictions of violence that they contained. But I always felt you were bringing that violence to the screen so we could transcend it, in a way.

LYNCH: Most films reflect the world, and the world is violent and in a lot of trouble. It’s not the other way around. The films don’t make a peaceful world violent—the violent world made the films.

DIEHL: In a way, though, the way you’ve reflected the very surreal world in which we live in your films has helped make surrealism itself a part of the popular cultural discussion.

LYNCH: Well, I don’t know. I love the surrealists, and I sort of understand what they’re saying, but I just think that maybe things aren’t always surreal. To me, a story can be both concrete and abstract, or a concrete story can hold abstractions. And abstractions are things that really can’t be said so well with words. They’re intuited. They’re understood in a different way, and cinema can do those things. Cinema is a great, great language for concrete stories, and concrete stories that hold abstractions, and abstract stories. It’s so much like music in that way.

DIEHL: Except for Dune (1984) and The Elephant Man, all your movies are set in America—and often a mythic America of your own making. What is the myth of America that intrigues you now?

LYNCH: I’m an American, and I love America, even with the problems we’ve got. Stories come out from where we live and what we hear and see and feel, so I don’t know what will come next. It’s like fishing: You just wait . . . I’m starting to catch ideas for the next film, but I don’t know what it is yet. It’s like I always say, “The chef cooks the fish, the chef doesn’t make the fish.” Desire is the bait, the fish is caught, and then the chef cooks it. Ideas are like fish. They just come to you sometimes, and when you’re really lucky, you fall in love with them and know exactly what to do.

Matt Diehl is a Contributing Music Editor of Interview