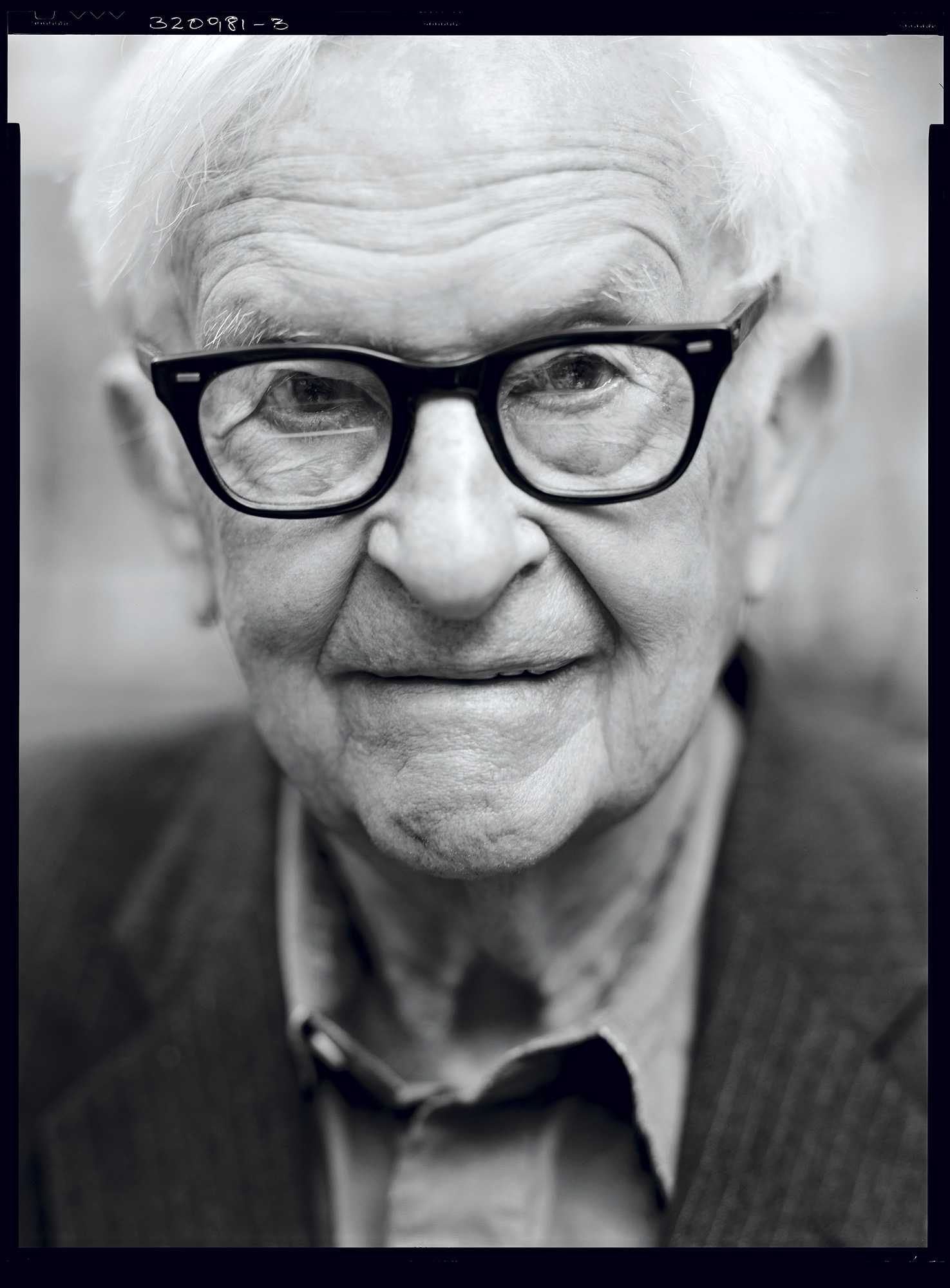

Albert Maysles

I ALSO FELT . . . THAT IT’S SO MUCH EASIER TO GO TO WAR WITH A COUNTRY WHEN YOU DON’T HAVE A SINGLE IMAGE OF AN ORDINARY PERSON . . .Albert Maysles

I was raised on TV dinners and the documentary films of Albert and David Maysles. Theirs are seminal, unforgettable works like Gimme Shelter (1970), an account of the 1969 Rolling Stones tour; Salesman (1968), which follows four door-to-door Bible salesmen as they levy their sales pitch to mostly beleaguered would-be buyers; and the astonishingly intimate and original Grey Gardens (1976), which takes us inside the decaying mansion occupied by the inimitable Edie Bouvier Beale and her mother, Edie Ewing Bouvier Beale, relatives of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy. In 2009, I had the privilege of producing a narrative adaptation of Grey Gardens for HBO. Albert and I traveled to the Emmy Awards in Los Angeles together that year, and shared, along with a few of my colleagues, the memorable walk up to the stage to accept an award for best TV movie. I think he knew we were going to win—his was the loudest voice cheering when the film’s title was called with the other nominees.

Albert is an inspiration to independent filmmakers everywhere—fiction and nonfiction alike. He and his brother David, who passed away in 1987 at the age of 54, directed their own work and produced some of it, taking notes from no one. The vision continues to influence generations through the Maysles Institute in Harlem, which is devoted to making and showing documentary films, and, of course, in Albert’s own films—when we meet, he has at least three projects going in different stages of completion. Albert and I recently got together for lunch at Red Rooster in Harlem, to talk about where he came from and where he’d like to go. After lunch, we walked around the corner to his art-filled townhouse to continue our discussion.

RACHAEL HOROVITZ: I wanted to ask you about your memories of growing up in Boston in the 1930s and ’40s.

ALBERT MAYSLES: We lived in Dorchester, and when I was 13, we moved to Brookline. The main reason being that my mother needed to work as a schoolteacher but she couldn’t teach in Boston because married women were not allowed to teach. So we moved to Brookline, but she found out right away she couldn’t teach there either because they’d never hired a Jewish teacher. She somehow managed to get an appointment with the school superintendent and convinced him to allow her to teach as a permanent substitute. So she never quite got the wages of a regular teacher. In Boston, in the ’30s, there was a lot of anti-Semitism.

HOROVITZ: So you were aware of that as a child?

MAYSLES: I was aware of it. Also almost every day some Irish kid would come up to me and say, “I’ll meet you outside,” which meant a fight. Oftentimes there’d be a whole circle of students—the Irish rooting for the Irish kid, the Jewish rooting for the Jewish kid, and when the fight was over, I didn’t think much of it. It was just another fight.

HOROVITZ: When did you first pick up a camera?

MAYSLES: Very young, probably when I was 10 or so. I didn’t have any money to buy one, but one day I was in a hardware store and I saw a brand-new camera for 35 cents. It was tiny, but it took pictures.

A TRUE DOCUMENTARY DEPENDS ENTIRELY ON OTHER FORCES. IT’S THAT HUMANIZING TOUCH THAT WE’RE MISSING OUT ON.Albert Maysles

HOROVITZ: Did you photograph your parents?

MAYSLES: Oh, yes, and the rest of my family. There’s a photograph—I don’t know if you noticed it in my office—of my brother sleeping. That’s one of my early photos.

HOROVITZ: I remember that. That’s a striking photograph. Do you wish that you’d been able to film your parents?

MAYSLES: Yeah, if I’d had a video camera, I would have been filming all the time. Another memory I have from that period is that families like mine— that is, lower-middle-class families—had the habit of punishing the child with the father striking the child with a belt. We always had that belt just in case, but my father never used it. But one day I must have done something terribly bad, and he hit me with it. It didn’t hurt. I didn’t think much of it, but later as I walked through the apartment I happened to pass his bedroom, and I looked, and there he was with his head against the wall crying. You don’t forget those things. With all the filming I’ve done, I’ve gotten very personal, but I haven’t gotten quite that close to what’s going on. That’s always been the goal for the next film I do.

HOROVITZ: You studied psychology. Was it just a natural progression from psychology to the camera?

MAYSLES: It seemed that way to me, yeah. The psychologist can’t counter things with a point of view, but always has to be open to whatever is really going on. I think I’ve developed a special talent for getting access to people. My wife is a family therapist, and she has said that when you first meet a subject, if your gaze is an empathetic one, you’re all set. And that process of empathy should continue all the way through the therapy. That’s precisely the basis for my own way of working with subjects.

HOROVITZ: That’s apparent in your first film, Psychiatry in Russia [1955].

MAYSLES: It was 1955. I was teaching psychology as a graduate student at Boston University. I also worked at a mental hospital. I’d been to Europe the year before, traveling around on a motorcycle, and I thought that if I went to Russia, I could dramatically humanize our conception of the people, just with photographs of ordinary people. And I also felt, as I still do, that it’s so much easier to go to war with a country when you don’t have a single image of an ordinary person, so that’s what I wanted to show. If the filming is done with love, then it’s very easy to engage in such a way where you feel that person’s experience as your own. And that’s why I make the films I do.

HOROVITZ: Originally, Psychiatry in Russia was going to be photographs. Do you remember what clicked in your brain that made you think of doing it on film?

MAYSLES: Because I thought that it would have a wider viewership if I did it on film—that I could get it on television, which I eventually did.

HOROVITZ: How did you end up getting over there to make the film?

MAYSLES: It occurred to me that I needed a way to pay for it. So I hitchhiked to New York, went to the office of LIFE magazine, showed them photographs taken in the hospital where I worked—actually, they were by someone else, but I claimed they were mine just so I could get the assignment. They were impressed, but not enough to finance my trip, though they did say, “We’d love to see your photographs when you come back.” So that didn’t quite work out, but as I walked down the street, I happened to notice this building that said CBS, and that was where Edward R. Murrow worked. I went in and asked to see him, and they said, “Oh, I’m sure he’d like to meet you, but he’s on vacation for a few weeks. You should talk to the head of the news department.”

HOROVITZ: That really happened the same day?

MAYSLES: Yeah. And I think it was the next day that I met with the news guy from CBS, Daniel Schorr. You know that name?

HOROVITZ: Yes.

MAYSLES: They gave me a movie camera, but I still hadn’t had any permission whatsoever to film in Russia. All I had was a one-month tourist visa. But more importantly, I met a reporter from Baltimore and I told him what I wanted to do, and he said, “Well, tomorrow I’m going to the Romanian embassy. There’s a special reception there celebrating the takeover of Romania.”

HOROVITZ: Wow.

IF THE FILMING IS DONE WITH LOVE, THEN IT’S EASY TO ENGAGE IN SUCH A WAY WHERE YOU FEEL THAT PERSON’S EXPERIENCE AS YOUR OWN.Albert Maysles

MAYSLES: And because he was a correspondent, he got an invitation. He said, “I’ll see if I can get one for you.” He couldn’t, but he says, “Come on anyway.” So we get there, and of course the KGB is at the door, and the reporter shows his invitation, slips it back to me, and then I show it, and they ask for my passport and see that is doesn’t match, and the KGB guy thinks this is very funny and lets us in. Within minutes I’m talking to top Soviet leaders, and I told one of them what I wanted to do. He set it up for me. “Just call this number,” he said. So I ended up with a 16mm camera and plenty of film, and I made my first film.

HOROVITZ: You used narration when you made it?

MAYSLES: I had to because I had no sound. I would have loved to have had sound.

HOROVITZ: When did sound enter your work?

MAYSLES: Five years later. My life has been a series of one lucky event after another. I happened to meet up with [D.A.] Pennebaker and Rob Drew and Richard Leacock at a time when they were all excited about making documentaries without narration. Drew had been a photographic editor at LIFE, and he had the idea of extending that way of shooting to do it on film. So I joined them, and we made a film called Primary [1960], about the primary election campaign between John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey. That changed everything.

HOROVITZ: How so?

MAYSLES: It was to be a film where there’d be no host, no interviews, just strictly observant—something that had never been done before. That started us on this whole thing of cinema vérité—or better called, direct cinema.

HOROVITZ: And that’s also around the time you started working with your brother David.

MAYSLES: Yes, and the two of us joined forces again in 1962 and made a film called Showman [1963], about Joseph E. Levine, the movie producer. We were off and running after that.

HOROVITZ: What kind of films were you watching in the ’50s?

MAYSLES: I must have seen the Italian Neorealist school of filming. That really touched me because it was so down-to-earth. I always felt strongly that too much of what we see is celebrities and not enough ordinary people.

HOROVITZ: Is there a film of yours that communicates your point of view more than the others?

MAYSLES: Salesman—if only for the fact that it was, in a very major way, changing from us going fist-to-fist with the Irish to handshake-to-handshake. We really did become friends with the salesmen.

HOROVITZ: There’s so much life in that film. It really is like an epic novel to me. How did you find those guys?

MAYSLES: My brother and I had both been salesmen—I sold Fuller brushes and encyclopedias for a while, and I think David sold perfume. So we understood the potential of the subject. And we thought, Wouldn’t it be interesting just to spend a little time in someone’s home? No one would dream of doing that sort of thing then. We hired somebody who was very good at casting to find people who were selling doorto- door, preferably in Boston. She discovered these four guys who were working for a company based in Chicago that sold Bibles. We didn’t know whether one of them would become more important than the others, which is what happened with Paul Brennan.

HOROVITZ: You followed them as they went door-to-door and inside the homes of these blue-collar people, revealing how manipulative they could be, how aggressive their sales pitches were. You really humanize the enemy to an exceptional degree in that film. In so many ways, I see its influence in narrative filmmaking and in writing today, where we root for the antihero. That has even come into the vernacular of big Hollywood movies. So many films by Martin Scorsese, who was a colleague of yours—and it sounds like you’re fans of each other’s work—are about protagonists that you root for even though they are involved in criminal activities. And it’s a given with Salesman that what they’re doing is almost criminal.

MAYSLES: Those guys hated what they were doing. People just couldn’t afford the Bibles, but they bought them—not for the spiritual content, really, but for the color pictures and the expensive binding.

HOROVITZ: What did Brennan and the others think of the finished film?

MAYSLES: We had a screening for them and for the company. They came to New York to see it, and I was sitting next to Paul, and it seemed like he laughed and cried at exactly the right time. He really, really understood it. I’ve since thought of the film in relation to . . . I forget who the poet is, but a famous English poet who said something like, “There’s no sound more beautiful, whether it’s in the city or in the country, than the sound of a knocking on the door.” To that I would add, “Unless it was a Bible salesman.”

HOROVITZ: It’s a masterpiece on so many levels and so layered. I was struck watching it again recently that, without overtly stating it, the film is making a statement about women. None of them are out working, they’re all at home, and they are easy prey. For the most part they’re happy to have the company and the attention from the salesmen. And you also see so many mothers and daughters, almost at each other’s throats, and then somebody comes in and breaks the tension in the room.

MAYSLES: It was so beautiful in the opening scene, when he’s having a hard time selling to a woman with her child on her lap. The kid gets down and goes to the piano and plays a few notes. That music is the perfect reflection of his depression. That’s the beauty of documentary filmmaking. It’s so much more credible.

HOROVITZ: It is. You make it look so easy, and I know that it is very, very hard.

MAYSLES: One of the things that makes it easy is that I have a true love for people. And so I have no difficulty getting and keeping access, because if something comes up that’s gonna be hurtful, they know—whether I put the camera down or not—that I’m not going to use it.

HOROVITZ: Did anyone ever get angry? Did you ever experience any kind of negativity from any of your subjects?

MAYSLES: I’ve been thinking about that recently. I can’t remember anybody. The closest thing to that was when we finished Gimme Shelter. We didn’t have a signed release yet and we showed it to the [Rolling] Stones, and Mick [Jagger] just couldn’t bring himself to sign off on it. A month went by. Three months went by. Six months went by, and my brother mentioned to a close friend of Mick’s that we hadn’t gotten the release. So he asked to see the film. We showed it to him, and he said, “Don’t worry, I’ll talk to Mick.” And he did. We got the release.

HOROVITZ: People focus on the violence that happened at the Altamont Speedway show, where a concertgoer was fatally stabbed during the Stones performance, and the reactions as that drama was unfolding. But there’s so much else that’s powerful in Gimme Shelter. There’s that scene of bodies in motion, of people listening to music, that is so powerful.

MAYSLES: My father would play classical music, and I would just look at his face. That was my music appreciation course. So I’ve always been conscious of faces and music. In Shelter, for example, there’s that beautiful scene where the camera goes from one face to another during “Wild Horses.”

HOROVITZ: It’s so beautiful. At a certain point, you started to break a wall and show your films within your films. In Shelter, we see the Stones watching footage of themselves. And I think that was an innovation, which, again, you made seem very simple but is actually a complicated idea.

MAYSLES: Normally something like that would be like staging something. But I wouldn’t call it that because, in this particular case, as the editing was starting, we remembered that the Stones had said, “We wanna see some of the footage before you edit.” And so we called Mick and said, “We wanna show it to you. And we might film you watching it.” Because that was something that the editor, Charlotte [Zwerin], particularly wanted.

HOROVITZ: So clever. Her work on those films is just high-end. Was she recognized for her work?

MAYSLES: Yeah. We insisted on three director’s credits. She’s given a co-director credit.

HOROVITZ: Well, I know from you, but I mean from the world at large . . .

MAYSLES: They don’t know. Everybody thinks everything is just one person. So why bother with all the others?

HOROVITZ: I know what that’s like as the producer. It’s hard to explain what you do when you really do everything and nothing.

MAYSLES: Right. And then the weird thing is that in documentary, nobody directs.

HOROVITZ: And shouldn’t.

MAYSLES: And shouldn’t. And of course what angered me so much when Pauline Kael reviewed Gimme Shelter, the whole pitch of her article, over and over and over again, was that everything was staged, when nothing was. Not that the critics thoroughly rely on what they see, but if they rely thoroughly on the film, then they’ve got the best source of what actually happened. And, unfortunately, they often misrepresent that. For example, so many reviews referred to the killing in Gimme Shelter as a murder. But we don’t know what the motivation was, so it would be more proper to call it a killing.

HOROVITZ: And so is the film a record? Is it reportage? Is it art? Or is it something in between?

MAYSLES: I think it incorporates both elements, and in many ways goes beyond ordinary reporting. Because a reporter’s not gonna spend a year on an article like we are making a film. And with Pauline Kael, what was particularly disappointing was that there was no “Letters to the Editor” page in the New Yorker back then, so there was no way to have it corrected. We wrote an answer to all of that and brought it to Mr. [William] Shawn, who was a very decent guy. He had us in his office, and he said, “Well, if what you’re saying is true, then we should have Pauline come here.” So apparently he tried, but I guess she wouldn’t come.

HOROVITZ: What a jerk!

MAYSLES: After that happened to me, I spoke to other people who were reviewed by Pauline, and a number of them had the same type of experience. She could be very nasty.

HOROVITZ: It’s so important when you make films to take the long view. And you’ve been so fortunate to be able to see the strength of your work over time and how it endures. So many people don’t have that satisfaction. What is the happiest time for you in the life of a film project?

MAYSLES: It’s so funny you should ask that. There were days when we were shooting Grey Gardens when my brother [David], Edie, Little Edie, and myself, we would all say, “We got good stuff.” So we all would shout spontaneously at the end of those good days, “It’s been a banner day!”

HOROVITZ: Yes!

MAYSLES: And we never filmed that. We should have. There were a number of those days.

HOROVITZ: Well, the day that the reviews of our version of Grey Gardens hit the papers, we all e-mailed each other, “It’s been a banner day!” Because we knew that story from you.

MAYSLES: Really? [laughs] You actually know two other things, perhaps, which are quite interesting. When we showed the two Edies the film, Edie [the daughter] had said, “The Maysles have created a classic.” And then, two years later, when Mrs. Beale was dying, she [Little Edie] happened to be with her and turned to her and asked, “Is there something we wanna say to the world?” She said, “There’s nothing I want to say. It’s all in the film.” It’s nice to be appreciated. They meant it.

HOROVITZ: It’s also a testament to you and to David, and something about your energy and style. That humanizing element, that touch that you have—that may be why your films still resonate so much with people. Just thinking about Grey Gardens, and how it has had different lives, as the film we did and also a musical on Broadway—how do you feel about it?

MAYSLES: Anything that you record, each person will apply their own point of view to it. And it emerges as something their own. That’s the whole nature of the process of producing a film and getting reception. So if someone wants to go further with something and make their own interpretation, that’s so much the better. It’s nice.

HOROVITZ: Is there anything that you would like to say in a film that you have yet to say? Anything that is incomplete, that perhaps one of your current projects is going to address?

MAYSLES: One is my train film—which is called In Transit, thanks to my wife.

HOROVITZ: It’s a fantastic title. It’s still your same direct-cinema approach? I assume it’s episodic.

MAYSLES: It’s about what happens on trains, but more importantly, what happens off the trains. The train gives you the opportunity to meet somebody, and find out what their story is when they get off. Each one of these stories is so spontaneous. I’m going to take trains in Western Europe, America, Brazil, South Africa, India, for sure, and possibly China. I’ve shot two things so far. We got on a train going across America, and after it picked up passengers in Pittsburgh, I was walking through the café car and I noticed this woman with two kids who looked kinda nervous. I asked politely if I could film her to make this movie of people I meet on trains. She said, “Yeah, sure.” And right away she told me that when she was 3 years old her parents broke up in an ugly divorce and she lost contact with her mother and she hadn’t seen her in 23 years. And the night before, she got a call from a woman in Philadelphia saying that she was her mother, and would she please get on the next train, that she would be waiting for her daughter at the station. So when she got off the train in Philadelphia, I continued filming. And in the station there was a woman at the top of the stairs who flung her arms open and ran down full of smiles. She wrapped her arms around her daughter, and they talked for awhile, and finally her mother turned to me and said, “Isn’t she gorgeous?”

HOROVITZ: Incredible. It’s amazing that you were there to capture that.

MAYSLES: I mean, a true documentary depends entirely on other forces. It’s that humanizing touch that we’re missing out on. Along with the vérité, if that’s what you want to call it, it’s what I’ve tried so hard to work into my films.

HOROVITZ: It’s interesting to think about how your work has been a precursor to the kind of extreme vérité of reality television.

MAYSLES: Yeah, I call it extreme non-vérité.

HOROVITZ: What do you think about reality TV? Have you seen any of it?

MAYSLES: I’ve seen the . . . What’s the name of that family? The Osbournes? I saw that. I thought that so much of the profanity was totally unnecessary and wrong. I don’t understand why there’s so much, even on programs like Jon Stewart, which I watch and like very much. When you think of exactly what they’re saying, it doesn’t add to the engagement or what might be the purpose of the program. It’s just a crazy kind of indulgence that doesn’t warrant any praise.

HOROVITZ: People are very conditioned to being filmed now and used to being on camera. There’s almost a kind of expectation that you will be filmed. When you started out making films, it wasn’t that way. I wonder, do you think that someone could approach those subjects the way that you did then and get the same kind of honesty?

MAYSLES: Well, I’m still making movies . . .

HOROVITZ: Always. I know you have several projects going on.

MAYSLES: We’re making a film about Iris Apfel, a fashion person who’s 90 years old. I’m also making a film about Pink Martini and Myrlie Evers-Williams. They’re going to perform together at Carnegie Hall. We start shooting that in December.

HOROVITZ: That is an unusual combination!

MAYSLES: It is. I’m going to use a lot of editorial help to decide how to put those together. But when I film a famous person, it’s really as I would an ordinary one. It’s a person, it’s under the skin, it’s the real person. And then you get into the commonality in us all, whether rich or poor, a celebrity or not.

HOROVITZ: I asked you, “What was the happiest part of the process?” because I’ve never seen you not happy. Whenever I meet you, you’re the happiest person in the room.

MAYSLES: Well, I have big problems though. It’s a big problem just keeping afloat, financially.

HOROVITZ: It is a big problem, and you’ve taken on a lot with the institute [Maysles Institute in New York]. Could you say a bit about the institute’s mission?

MAYSLES: Well, it has two things to do that are quite special that there’s not enough of, and that is, first of all, to show documentaries, exclusively. There’s nowhere else in the city where you can only see documentaries. The second part is teaching kids how to make films.

HOROVITZ: And they’re all nonfiction films?

MAYSLES: Yeah. And just recently we had a graduating class of a dozen kids. They had just projected their films, and they’re standing in front of the audience taking questions, and one of the questions was, “Are any of you planning to become documentary filmmakers?” All the hands went up. That was a special moment.

HOROVITZ: That was a banner day.

MAYSLES: That was a banner day, a banner moment. What we do can have some impact on the world.

HOROVITZ: The world has changed, and I wonder if you feel that it’s financially harder now to make nonfiction films.

MAYSLES: It’s always been hard. I think there are more opportunities now with DVDs and the Internet.

HOROVITZ: Why did you keep at a job that was so difficult and frustrating?

MAYSLES: Oh, it’s so important. It’s so satisfying. I never thought it’d make me professional or otherwise. I thought I’d just have a secure income and search around for something else. But I was somehow able to survive. My wife [Gillian] is a therapist, and she works from 8 in the morning till 10 at night. Fortunately, she comes back to take care of me, and I’ll say, “I’m so hungry,” and she’ll give me dinner.

HOROVITZ: That’s very romantic.

MAYSLES: Did I ever tell you the story of how I met her? With Salesman, we felt we were making a new kind of documentary, and we thought, Oh, all the distributors will want to see this film. But none of them were interested. So we raised enough money to rent a theater and we had a screening and maybe a hundred people showed up. They congratulated me, and when it ended, I noticed there was just one person left in the theater. When she got up to leave, I saw that she had been crying. As she got closer, I saw how attractive she was, and I elbowed my brother and said, “She’s for me.” That she’d been for me all along. Romance, huh? What’s more romantic than the whole process of making a film and, moment to moment, discovering something that you couldn’t imagine?