The Restless Wanderings of Gideon Lewisâ??Kraus

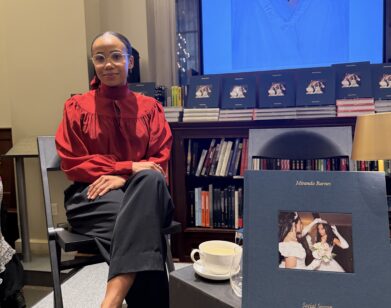

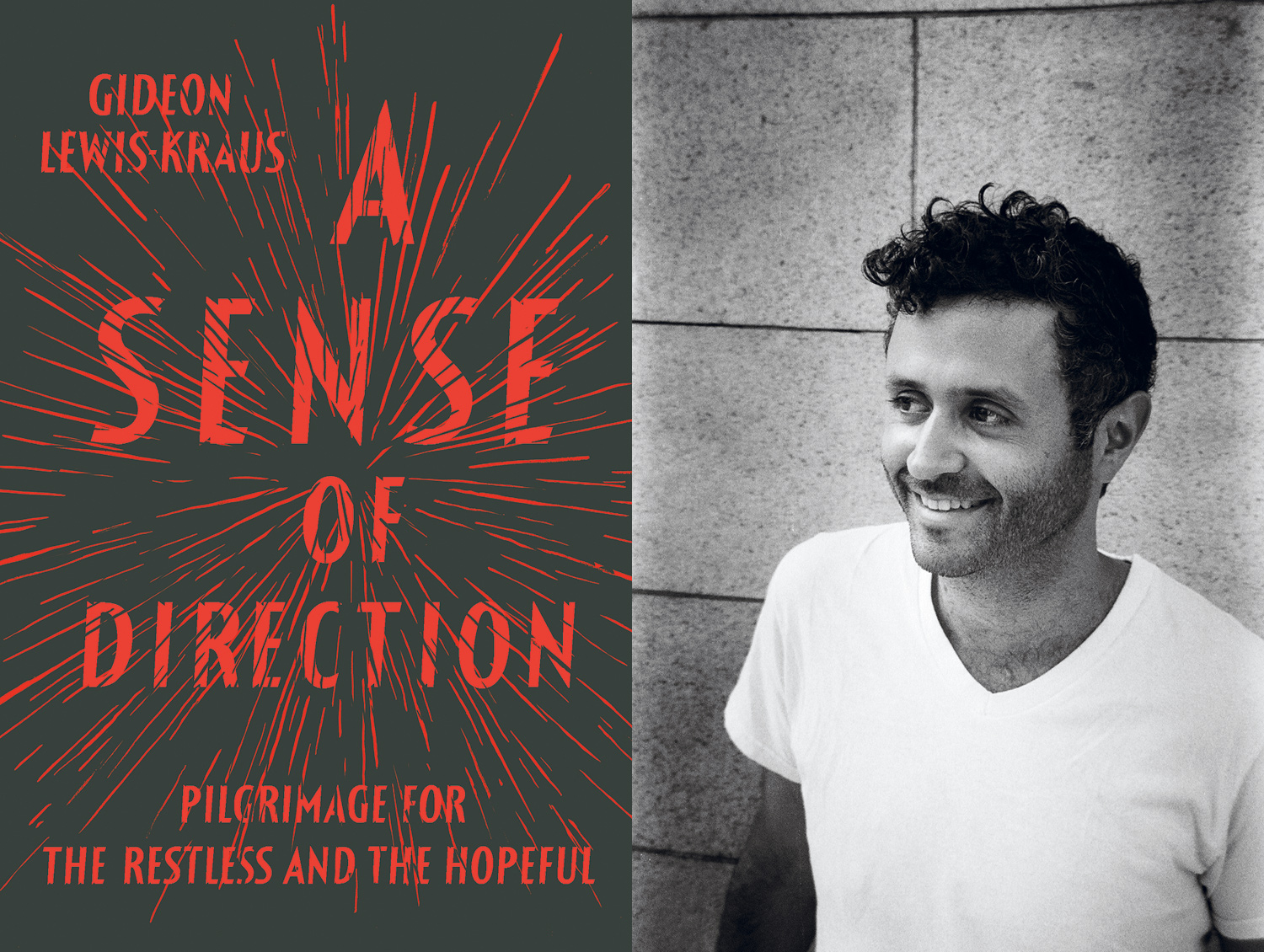

Readers of Gideon Lewis-Kraus’s articles for Harper’s, n+1, and The Believer will know his skill at weaving digressive anthropological observations into cohesive narratives. The 32-year-old writer has produced canny and biting critiques of spectacles high-, middle-, and lowbrow alike, among them the Modern Language Association’s annual conference, the Frankfurt book fair, and a (forthcoming) study of the phenomena of cats on the Internet. In A Sense of Direction, his first book (Riverhead), Lewis-Kraus considers the mythology of the pilgrimage and how that medieval ritual might reward the modern, secular wanderer. Lewis-Kraus himself is the protagonist.

When Lewis-Kraus moved from San Francisco to Berlin at the age of 27, armed with a Fulbright, he was hoping to cure more than his restlessness. He figured that if he crammed enough experience into his untethered 20s, by the time he got to his 40s, he wouldn’t wonder what else was out there, what he might have missed. He wouldn’t bail on his responsibilities like his own father, a rabbi who came out at the age of 46, leaving his wife and two sons for a man he met at the gym. The fantasy that he could preemptively quash similarly destructive impulses, is what compelled Lewis-Kraus to embark on a series of pilgrimages: the Camino de Santiago, in Spain; the Japanese island of Shikoku; and the Ukrainian village of Uman.

It all began unceremoniously. At some point over several days of partying in Estonia, he and a friend, the writer Tom Bissell, made a pact to go on the Camino, a medieval pilgrimage route across Spain. That 500-mile journey, during which Tom’s feet are “shredded,” sounds like a leisurely stroll compared to the next adventure: Lewis-Kraus’s rain-soaked 745-mile solo journey around the periphery of Shikoku. For the final Ukranian odyssey, he recruits as traveling companions his brother and his father, from whom Lewis-Kraus intends to demand a full accounting of the past.

Interview met Lewis-Kraus one afternoon at a downtown restaurant between lunch and dinner. He arrived in a white T-shirt and jeans, his boyish face partly obscured by a scruffy beard. Nursing a bloody Mary topped with a salad-size garnish of skewered vegetables, he talked about walking the line and where he landed (psychically and physically) when he finally stopped.

MEGHAN DAILEY: From the beginning of your first pilgrimage, the Camino, you wrote a lot of e-mails that became the book. Is that how you wrote all of it?

GIDEON LEWIS-KRAUS: It’s basically the way I write everything. It’s so much easier to write in the form of an e-mail box, because you’re primed by routine. It’s a space where you can go on in a casual way.

DAILEY: It’s a discursive space.

LEWIS-KRAUS: It’s where you think about audience and you think about entertainment. On the Camino, at the end of every day, I would write in my journal, and when Tom and I found an Internet cafe I’d type it up and send it to 50 or 60 people. But I also revised very heavily. I probably rewrote the Camino chapter at least 15 times from the ground up. The subsequent trips kept changing my impressions of the earlier trips. My perspective on so much changed.

DAILEY: Part of the reason for your wanderings was that you thought that by obeying your desires while you were young and free do to so, your older self would be left with fewer regrets. In a way, you were trying to outsmart your own future.

LEWIS-KRAUS: I was trying to look at my life in my 20s from the perspective of my life in my 40s, in a way that I felt my father hadn’t done. The foil for so much of this in the book is my dad’s life. And I thought, okay, look at all the costs of his decision to settle at a young age in a way that ultimately he would see as not really his life—or that’s the way I thought about it. I thought that his life was such a clear portrait of what the costs of doing something that made you feel unfree were that I went so far in the other direction that it took a long time to realize that there are a lot of costs associated with what seems like freedom.

DAILEY: You describe a pilgrimage as “an exercise in freedom from the necessity of articulating your motives without too much exactness.” We do that in our ordinary lives too, and in a way, maybe that’s what your father was doing for a long time. Normal human behaviors are magnified on the pilgrimage.

LEWIS-KRAUS: That’s what travel is, even non-religious travel—days are magnified and days are experienced more intensely, because you’re bracketing them as something that somehow isn’t real life. Though of course, it is real life.

DAILEY: But because of the conditions, you adjust your expectations of people.

LEWIS-KRAUS: Exactly. You’re simultaneously lowering what you need out other people and also hoping to rise to the occasion. One of the things the book is about is what it means to try to rise to an occasion and the ways in which you’re invited by these experiences to try to rise to the occasion.

DAILEY: And what does that mean? Make every day special? To continue the journey and be present for other people?

LEWIS-KRAUS: A lot of those things. And another is to realize that, as my brother reminded me when I started to complain to him over e-mail from Japan about how miserable it was and that my feet hurt and how lonely I was: I chose to do this. And part of rising to the occasion is remembering that I’m lucky enough to do this and I shouldn’t be complaining.

DAILEY: You were really lucky. Reading it from where I am, I’m sort of envious of your position. The walking was a labor and so was the writing, but you weren’t really tied down by employment, and there is a kind of privileged position that you were coming from.

LEWIS-KRAUS: Well yes, except that I was supporting myself the entire way, it’s not like anyone else was paying my rent. In Berlin I had the fellowship and I was writing for some magazines. Part of the reason I had moved to Berlin in the first place was because I didn’t want to be worrying so much about how much my rent cost.

DAILEY: Not just economically.

LEWIS-KRAUS: Emotionally?

DAILEY: There’s just a sense throughout that you can do whatever you want. And there’s something incredibly compelling about that for people who, for whatever reasons, can’t.

LEWIS-KRAUS: People in my life, like my mom and my brother, were constantly reminding me how incredibly lucky I was. But the longer I went on, the more I thought, “No, you’re lucky to be so nicely rooted in a life with your girlfriend and your nice apartment and your job [even] though you might feel sort of trapped.” But actually, by the end I had a very strong sense of all of the costs of that freedom. In the process of writing this book I was not in the same place for more than 10 continuous weeks for almost three years. I didn’t feel grounded in the kinds of routines that make you feel like you have a comfortable life. I didn’t have a girlfriend or an apartment. I didn’t own anything.

DAILEY: The book plays on the travelogue-memoir genre by being very self-conscious and critical of the idea of the transformative journey.

LEWIS-KRAUS: There are obviously appealing things about the quest narrative, because you don’t have to think too hard about the structure. But as I started to read other people’s accounts of their pilgrimages, what struck me is how boring so many of them are. And so many of them are the same. All of them stop at the end of the trip. Nothing is written from the perspective of the person going back to their everyday life. I thought there was something really disingenuous about that.

DAILEY: A soft landing is one limitation of that conceit.

LEWIS-KRAUS: There’s a real problem with the quest narrative. That concept gets complicated and undermined throughout the course of the book. Either you’re going to give a narratively satisfying climax, which is the person getting to the end of the Camino and being reborn. But that’s total bullshit emotionally. As much as every reader wants to believe that you get to Santiago and you’ve been reborn, we know it’s not what happens. But on the other hand if you write that you got to Santiago and all you did was stop walking, which is basically what happens, then that’s narratively unsatisfying. I wanted to think about what the experience meant. That’s why it’s important that it took me a couple of years to write this book because I had to deal with how it was all playing out in my life over time.

DAILEY: You ask your father and your brother Micah to come with you to Ukraine for the last pilgrimage to the village of Uman, where tens of thousands of Hasids go to celebrate Rosh Hashanah.

LEWIS-KRAUS: That’s where it became not just this personal story but a family story. We’re going to go now, under the pretext of a religious pilgrimage, and I’m not going to have this quick intimacy with people I don’t know, but I’m going to have the tough conversations with the person who is most problematically close. This is no longer about the personal test of walking 500 miles and somehow feeling purified. We’re going to this awful place in the Ukraine and we’re going to stand before each other and address these issues for real.

DAILEY: The drama was in the conversations between you, your brother, and your father. But there was a very different kind of energy surrounding you.

LEWIS-KRAUS: Although there were more complicated things going on about choice and about endurance, the Camino had in my memory become this fun thing. In the Ukraine, I actually met these people who were on the pilgrimage for explicitly religious reasons. These were people who had extremely narrowly circumscribed lives. They weren’t dealing with the questions I dealt with about the surfeit of choice and how to deal with the cost of our decisions. So I had to engage in different ways with what choice meant. Over the course of the book, I say, well, there are a million reasons for doing this and maybe there’s not such a difference between a walk and a serious religious thing. But in the Ukraine, it became much clearer what those differences were.

DAILEY: In the midst of this, you planned to confront your father. What did you hope would happen?

LEWIS-KRAUS: I had always felt so deceived by him and his story had changed so many times, I had this hope was that I was going to nail it down and get it in print and hold him to a final account. But then of course he and I had these conversations and I realized he wasn’t changing his story to be deceptive, he was just figuring it out as he went along. And there’s no such thing as holding someone to a final account. That had just been a fantasy of mine. Through his really candid answers to my questions he showed me that he was just muddling along doing his best. What has been important is the respect and the honesty that we have shown each other in beginning to have those conversations.

DAILEY: What has your relationship been like since?

LEWIS-KRAUS: It’s been amazing. I was really afraid for a long time to show him the book, then I finally sent it to him when I was going to be out of the country. I thought that maybe he was never going to talk to me again. I finally got an e-mail from him that said “I haven’t really known how to respond. There were so many things that were really hard for me to read, but ultimately this book has been redemptive for me and I’m sorry for everything.” It was so open and meaningful. And the past six or seven months we’ve been getting along better than we ever had. Whatever happens, simply as a process of reconciliation the book was completely worth it. It so exceeded my expectations of what it would ever do.

A SENSE OF DIRECTION IS OUT NOW.