Price Wars

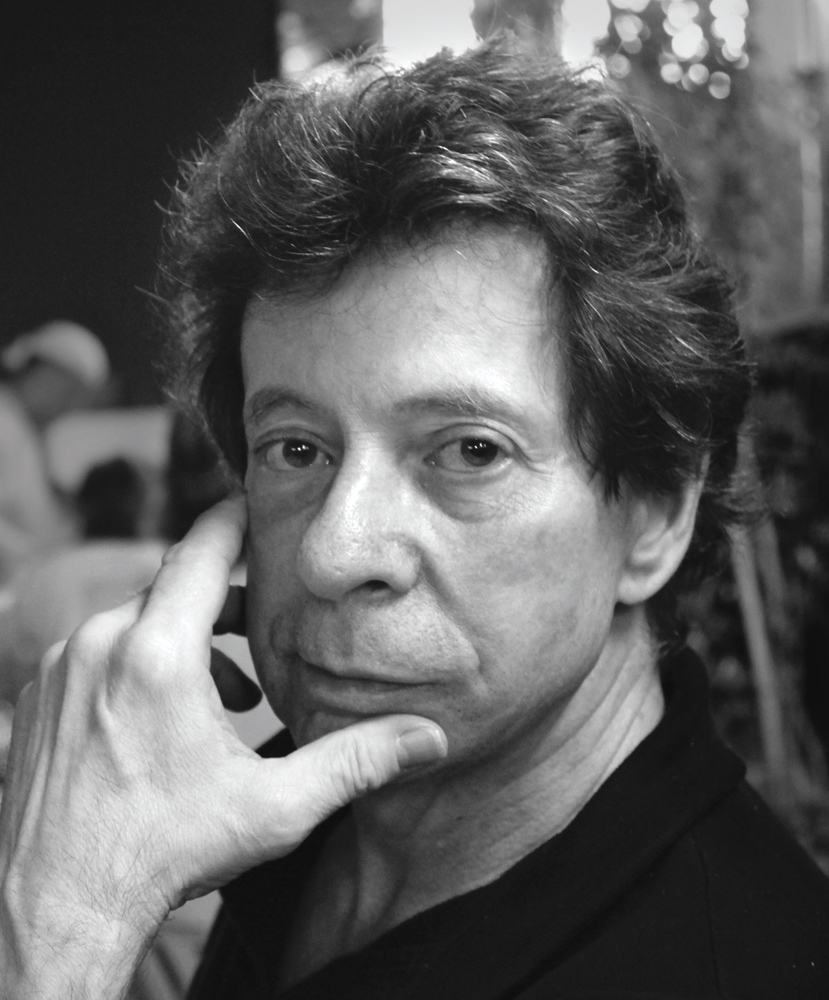

ABOVE: RICHARD PRICE. PHOTO COURTESY OF LORRAINE ADAMS.

Stepping into Richard Price’s brownstone from the unforgiving snow covered streets of Harlem is like walking into a swirling, bohemian caravan of dreams. There is the wood, gleaming and immaculate without a lick of paint or sandpaper ever having touched its rich coffee-hued grain. The walls are adorned with artwork; there’s an expansive framed Iranian fabric. Even the intricate tiles in the powder room floor are woven mosaics evoking the Mediterranean.

“Sometimes the best part of going out is coming back home,” Price says in his thick New York accent.

A famed author and screenwriter, Price grew up in a housing project in the Bronx and is best known for penning gritty urban crime fiction (from novels like 1974’s The Wanderers, 1992’s Clockers, and 2008’s Lush Life to film and television screenplays such as The Color Of Money, 1986, Sea Of Love, 1989, Ransom, 1996, and HBO’s The Wire). He still lives in New York with his wife of three years, fellow author Lorraine Adams whose own novels stretch from Pennsylvania to the Middle East. If Adams’ influence has contributed to their home’s Persian aesthetic, the characters in Price’s novels would know a thing or two about the property’s former function as a crack house.

The Whites, Price’s latest novel written under the under transparent pseudonym “Richard Price writing as Harry Brandt,” could have been set in the New York of the ’80s or ’90s, when his home’s previous occupants were synonymous with the city’s crime-ravaged image. It’s a compulsive, gritty police procedural with Price’s trademark: dead-on dialogue. At the center of everything is Billy Graves, an NYPD nightshift Sergeant, old before his time, who lives in Yonkers with his wife Carmen, two sons, and a retired detective dad who suffers from dementia. Graves suspects his old crew, the self-anointed “Wild Geese,” have turned vigilante, seeking to wield street justice on “The Whites,” the perps that got away. Meanwhile, his own family is under threat from a psychopathic loner officer still in the force. The book has already been optioned by Sony Pictures with Scott Rudin producing.

JEFF VASISHTA: New York is gentrifying at an alarming rate. Do you think the gritty New York you’ve written about for so long is in danger of disappearing?

PRICE: It is and it isn’t. You’ve got those giant towers and oligarch pied-à-terres for over $50 million. I don’t care how many hip Japanese couples move in or people like me, artistes. Harlem will always be Harlem. You’ve got this building across the street. Does that look gentrified to you? Think of the Lower East Side—Rivington, Stanton, Orchard, Ludlow. Yes, there are boutiques there but that’s just the epicenter. There are also a million housing projects there. It’s huge. It’s so complicated.

VASISHTA: There has obviously been a lot of focus recently in the media about racism in the NYPD, but your characters are noticeably multi-cultural. Do you think it’s an accurate portrayal?

PRICE: I like to go all U.N. with my cast and characters. I always have. I’ve always been interested in writing like that. It sounds so P.C. that I wanted a rainbow coalition. It wasn’t hard because it’s New York. Cops are not monolithic. For an immigrant group, being a cop is an entrée into the culture. It’s a way to be an American fast.

VASISHTA: Your books sell on strength of your name alone, why choose the pseudonym Harry Brandt? You’re not denying it’s you.

PRICE: My initial intention, and therefore the pen name, was that I was going to write a traditional urban thriller—what you see is what you get. What was going to propel you through the book was, “Who did it?” That’s why I used the pen name. I decided to slim myself down to write this in this way and it fell apart and became like all my others, where it becomes something bigger than just the story.

VASISHTA: So why not scrap Harry Brandt when you realized it was classic Richard Price?

PRICE: There are contractual reasons why I needed to use a pen name to duck out of obligations I had to another publisher. I thought this book would be so different from my others I’d want a different name for it.

VASISHTA: Is there a novel in you that you’re dying to write that doesn’t include New York and the police?

PRICE: I doubt it. It’s [about] crackling. As another writer once said, “I don’t know how to make doctors funny.” Street people, cops, urban people, I know how to make them crackle. I don’t know how to make lawyers crackle.

VASISHTA: What do you find the most difficult aspect to writing?

PRICE: Structure. I’m terrible at structure. I know what I want to write about. I know my characters. Usually I’ve spent enough time with the people I want to write about to the point where I can “do them,” I can impersonate them. The most difficult part for me is, “What’s the story and how does the story get laid out?” I’m so much more interested in my characters and situation, but I’m not so hot on, “This happens and then this happens.” That’s why I gravitate towards police investigation. I think police investigation is fascinating to me, but if I see a panoramic landscape that I want to get into, how do you get into an amorphous mass? If you follow the orderly procedure of a police investigation, you get a spine to your story. I’ve been leaning to the procedural thing to help me lay a skeleton that I can lay muscles and veins and a skin on.

VASISHTA: Do you ever workshop your stuff with a group of writers?

PRICE: I’d rather kill myself than subject myself to a workshop. I used to teach in MFA programs. I have an MFA. You just never know what people are going to say and why they’re going to say it.

VASISHTA: So where do you get your feedback from?

PRICE: I work closely with my editor. I was always worried about living with another writer, but my wife is a novelist. I trust her. I don’t think that she’s ever going to say anything for a reason not about the work. You always worry if you live with someone and you ask them for feedback on your novel or painting that they’re always going to say it’s worse than it is or better than it is, probably for reasons that having nothing to do with the objective assessment of the work. But I totally trust my wife. She trusts me, and we use each other. I didn’t think that I would ever have a relationship like that but I do. It’s great. Once I get into the deep process, the most important thing is not who’s publishing you, but who is your editor. If you have a great editor at a lesser house it’s better than being at a high prestige house but with an editor you’re not clicking with. To me it’s all about the editor.

VASISHTA: Does writing still hold the same importance to you now as it did when you were younger?

PRICE: Writing for me used to be life or death. My reviews were very important to me. At this point in my life I feel it’s more spread out. I’m older. Writing is fiercely important, but my relationship with my wife is extremely important too. When I had children that was a huge part of my life but my children are grown. I like what I’ve carved out for myself and writing is just a part of it.

VASISHTA: Were you a tough person to live with before?

PRICE: Yes. I went in and out of feeling happy. There were a lot of unresolved things in me and I tended to be more churlish. I was more unfocused. If I wasn’t writing I didn’t know what to do with myself. I don’t feel that way anymore. It’s not like I have hobbies, but I don’t feel like, “If they don’t like this book I’m going to die.”

VASISHTA: How did you work through that?

PRICE: Just by living. Finding peace. Things take care of themselves. I was a very unsettled person. Now I feel fairly settled.

VASISHTA: How do you balance your screenwriting and novel writing?

PRICE: It’s getting harder and harder to get gigs. People in Hollywood have tiny memories of you if you haven’t done anything in four or five years. They were probably still in school four or five years ago. I have a movie coming out in April, Job 44. Usually for money I go to TV to create pilots. Scott Rudin bought The Whites. I’ll be writing the screenplay. It’s very difficult doing your own book. It’s not like a dream job because you’re connected to it. It better to adapt someone else’s book because you’re not constantly fighting to keep as much as you can. You have do dissect a book and you have to do it in a heartless, surgeon-like way because it’s a different medium. I always found it really brutal to adapt my own stuff. There were things that other people would say, “Oh, this has got to go” and I had a hard time with it. It was my baby. It’s like taking an arm off your child. The only thing a screenplay owes a novel is just to capture the spirit of it. Making a movie is like speed chess; it’s not the grand masters. We’re playing in Washington Square Park on a stone chess table with some homeless guy and we’ve got to hit that clock every two seconds. You’ve got two hours to tell a story—go!

VASISHTA: You say that you’re more balanced and writing isn’t the be-all-and-end-all as it once was for you. Is that scary because you’ve defined yourself by being a writer for so long?

PRICE: Yes, because it’s a nascent feeling. I’m 65 years old and I’m so conditioned to feel like it’s all about the work. Now it’s not all about the work. It’s about a lot of things. Also, just getting used to feeling pretty happy on a day-to-day basis.

VASISHTA: Were you depressed a lot before?

PRICE: I was intense and unsettled. My writing was way too important to me. It’s what you do, but it shouldn’t be all consuming. Someone once said, “No one got up from their death bed and said, ‘I should have spent more time at the office!'”

THE WHITES COMES OUT TODAY, FEBRUARY 17, VIA HENRY HOLT AND CO.