New Again: Sam Waterston

Actor Sam Waterston is recognizable for many roles: most recently he portrayed Sol Bergstein in Netflix’s Grace and Frankie, and prior to that he took on Aaron Sorkin’s exacting dialog as Charlie Skinner on the HBO series The Newsroom. He is perhaps most famously known as Jack McCoy on Law & Order, a role he occupied for 16 years and 20 seasons (and, according to rumor, one he might reprise in a series reboot on NBC in the near future). But Waterston doesn’t only appear on television and film screens; much of his acting has taken place on the stage. In 1975, the Cambridge, Massachusetts native starred in his first Shakespeare in the Park production with the role of Hamlet. Today, he returns to the stage—or to the park, rather—with The Tempest, his 10th Shakespeare in the Park production, which will run through July 5th. In honor of his homecoming to his public theater roots, here we revisit an Interview article from April 1981 that uses a simple phrase to encompass Waterston’s finesse at his craft: he’s an “actor’s actor.” —Haley Weiss

Actor’s Actor

By Martin Torgoff

While others in his profession chase megabucks and the sex-symbol status of superstardom, Sam Waterston quietly and steadily devotes himself to perfecting his craft. He has emerged as one of the most accomplished and versatile talents on the contemporary American stage. His range includes everything from light comedy to classical drama and virtually every format available to the serious actor: Broadway, Off-Broadway, regional theater, film, and television. In 1963, he starred in the New York Shakespeare Festival’s production of As You Like It, and made his Broadway debut in Arthur Kopit’s Oh Dad, Poor Dad. His off-Broadway credits include, among many others, Ann Jellicoe’s The Knack (1964) and Sam Shepard’s Obie-winning La Turista (1967). As Bennedick in Joseph Papp’s innovative production of Much Ado About Nothing (1972) he won an Obie and a Drama Desk Award; then, in 1973, he played Tom Wingate opposite Katherine Hepburn’s Amanda Wingate in a stunning television production of Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie and followed his critically-acclaimed performance with a turn as Prospero in a Papp production of The Tempest. In 1974, he found himself cast as Nick Carraway in the film version of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, with Robert Redford and Mia Farrow (critics claimed that film, on the whole, missed its mark but hailed Waterston’s performance as memorable and distinctive in an otherwise muddled work). The following year he exploded on the stage of the Beaumont theater, first in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House with Liv Ullman, and finally in a towering Hamlet. In 1979, he appeared in Woody Allen’s Interiors and as C.D.B. Bryan in the television movie Friendly Fire (with Carol Burnett and Ned Beatty). He was then cast as Canton, the ruthless cattle baron in Michael Cimino’s epic Heaven’s Gate. He is currently featured as a CIA agent tracking down Walter Matthau in Hopscotch and on Broadway in Jean Kerr’s romantic comedy Lunch Hour. And stay tuned to PBS this year for the airing of a sevent-part BBC production of Oppenheimer, a mini-series based on the life of later nuclear scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer.

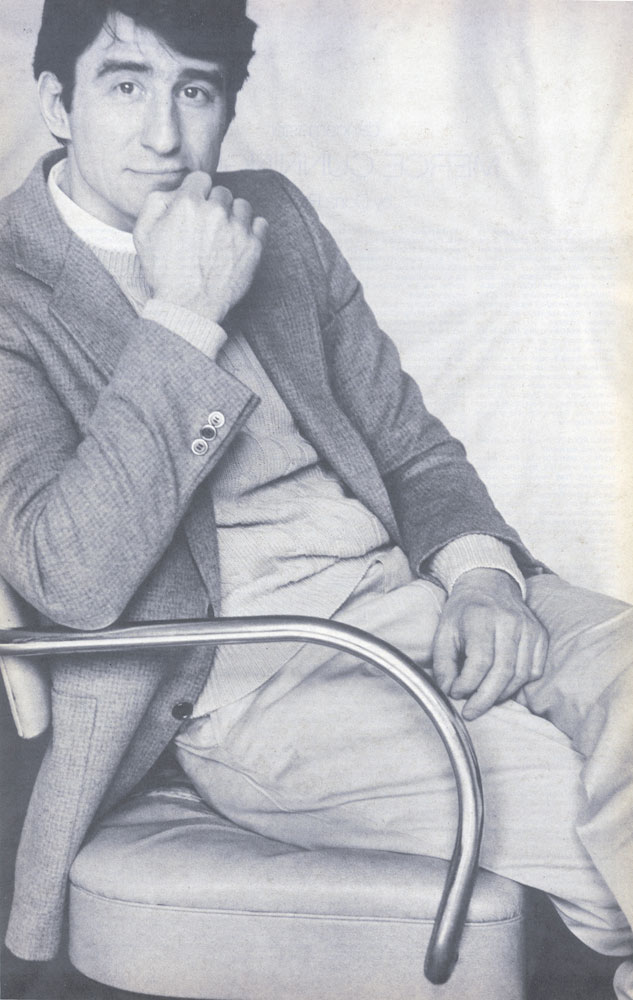

Last night, I ambled backstage of the Ethel Barrymore Theater on Broadway where Sam received me graciously. A rangy-tall figure brushing his longish hair back with his hand, he is darkly handsome in an understated classically small-town U.S.A. kind of way, his face a collection of bold, angular lines all crinkling up when he smiles, his eyes sensitive, mirthful, sardonic, keenly intelligent and expressive—two pools of brown warmth.

MARTIN TORGOFF: What attracted you to Lunch Hour?

SAM WATERSTON: The bunch. The fact that Robert Whitehead was producing it and Mike Nichols was directing. I didn’t know Gilda [Radner] was going to be in it.

TORGOFF: Do you ever want to be big?

WATERSTON: Big? Sure. If you’re not moving forward, you’re falling back—that’s the way it is. In order to continue to do interesting work, you don’t have to be ‘big,’ but you need to be…proceeding. And I guess there comes a point when they say—whoever ‘they’ are—that you’re good. Period. And yes, then people are regularly interested in you—you’re doing interesting things. That’s where I’d like to be: when the business says here’s a good actor who is marketable so we can use him. Just that. I don’t care how big that gets. There’s a level of celebrity beyond this, I don’t think there’s anything to be desired in a bunch of people chasing you around, trying to get a piece of your clothing.

TORGOFF: But don’t all actors want commercial success and recognition?

WATERSTON: I think people have some control over what they want; there’s a relationship—maybe not automatic—between what you want and get. The commercial success you’re talking about is like Jack Nicholson, for instance, who has done very interesting work and is hugely successful—and he’s a wonderful actor—he’s done it all in the movies. It’s one thing to say it was fortunate I didn’t get swept off into the movies at a young age because then I wouldn’t have done Shakespeare.

TORGOFF: Do you stay here in the city much?

WATERSTON: A couple nights a week, usually. I live far away, in Connecticut—it’s a long drive. I don’t like driving much; it was my miscalculation about moving there with my family, but I didn’t want to live in a suburban town. I wanted either the city or the country, and I didn’t want a weekend place because I didn’t want to feel like a visitor in the place I cared most about. So we moved. The kids have the same thing about moving to the country after they’ve seen Paris as the grown-ups do; my daughters are real young but my oldest really registered what city life was like and I think he’d like to come to town a bit more; but the virtue of the country is that it makes you thirsty for the city. You get steadied by that atmosphere out there.

TORGOFF: Tell me about Heaven’s Gate. I never got a chance to see it.

WATERSTON: Listen, I don’t know why they closed it. They said they couldn’t tell what the story was about, but I knew—it was clear to me, but then again, I had the script!

TORGOFF: From reading the reviews, you get the impression that maybe 50 years from now, the film historians will drag it out and exhume it, and the post-mortem will treat it like the films of Erich von Stroheim, like a curiosity or a famous failure.

WATERSTON: I don’t know, I was just in it. I don’t know what they’ll do with it. I think the way they handled it was smart—they’ll release it again, I hope. This I do know about it, the film has some real virtues. There are some wonderful performances.

TORGOFF: Making that film must have been like going off to war, or going off on a polar expedition.

WATERSTON: Well, it wasn’t really hardship conditions, just a long commute to work. We were in beautiful country—Glacier National Park. But what happens is that you get this kind of cabin fever. If you were there on your own camping, it would have been one thing; but because you had to be there, it was something else. Six o’clock every morning. On the way to one of the locations was a little town called Poleridge, with a bunch of cabins by the river. I took one. It was nice…also long, boring, a lot of waiting. The bigger the movie, the longer the waiting. Snowstorms. Spring. The whole forest was blanketed by yellow wildflowers. Grizzly bears eating the bushes. My family came out some—you got Home Leave once in a while, too. Nobody anticipated how long it would take, which added to everyone’s restiveness. Like going out on a police action and discovering that you were in a major war.

TORGOFF: It must be hard leaving your family and going off on location for months on end; it must be harder on them than you.

WATERSTON: Still… when you’re home, you’re really home; its not nine-to-five everyday to a job. We have this old farm and we plan to make it into a working farm again. I don’t know how far we’ll get right now—it’s an ambitious project. I’ve been away a lot; the six months I was doing Oppenheimer we all went to England, so that was nice. When I know I’m going to be gone for a long time, we just all go together. I don’t think we’ll be able to do that very much longer, though. Separation is painful, and there’s such a thing as doing it too much—the limits are how much it hurts. But it’s not a life that depresses you, if you’re making a decent living and getting to do the work you want to do and you get to spend as much time with your family as anybody else—maybe on a different schedule—you really don’t have a lot to bitch about, you know?

TORGOFF: Did you always now that you would be an actor or did you have that moment of recognition when it stared you right in the face?

WATERSTON: I did have that moment. I played Lucky in Waiting for Godot at Yale and it was a thing that Stanislavski talks about: he says you don’t need his ‘method’ if you can count on your inspiration and it was a moment of inspiration that came to me, not in rehearsal but on stage. It hit me right there in the middle of the play and it was great—it travelled into immediate communication. I had this sudden, wonderful understanding about the character just the instant before I was supposed to speak, and there wasn’t any time to think about whether it was a good idea or not—it just went bam! It worked like gangbusters. I had a palpable sensation of control from my fingers out to the audience, that what I did affected them, and I thought: My God, this is wonderful! I have had the same experience in other areas since then—not only the theater can give you that, I had it skiing once. I’d been learning to ski parallel for weeks and then I just floated down the hill, really fast, and I knew I wasn’t going to fall. I just got really high and clear.

THIS INTERVIEW WAS ORIGINALLY IN INTERVIEW‘S APRIL 1981 ISSUE.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.